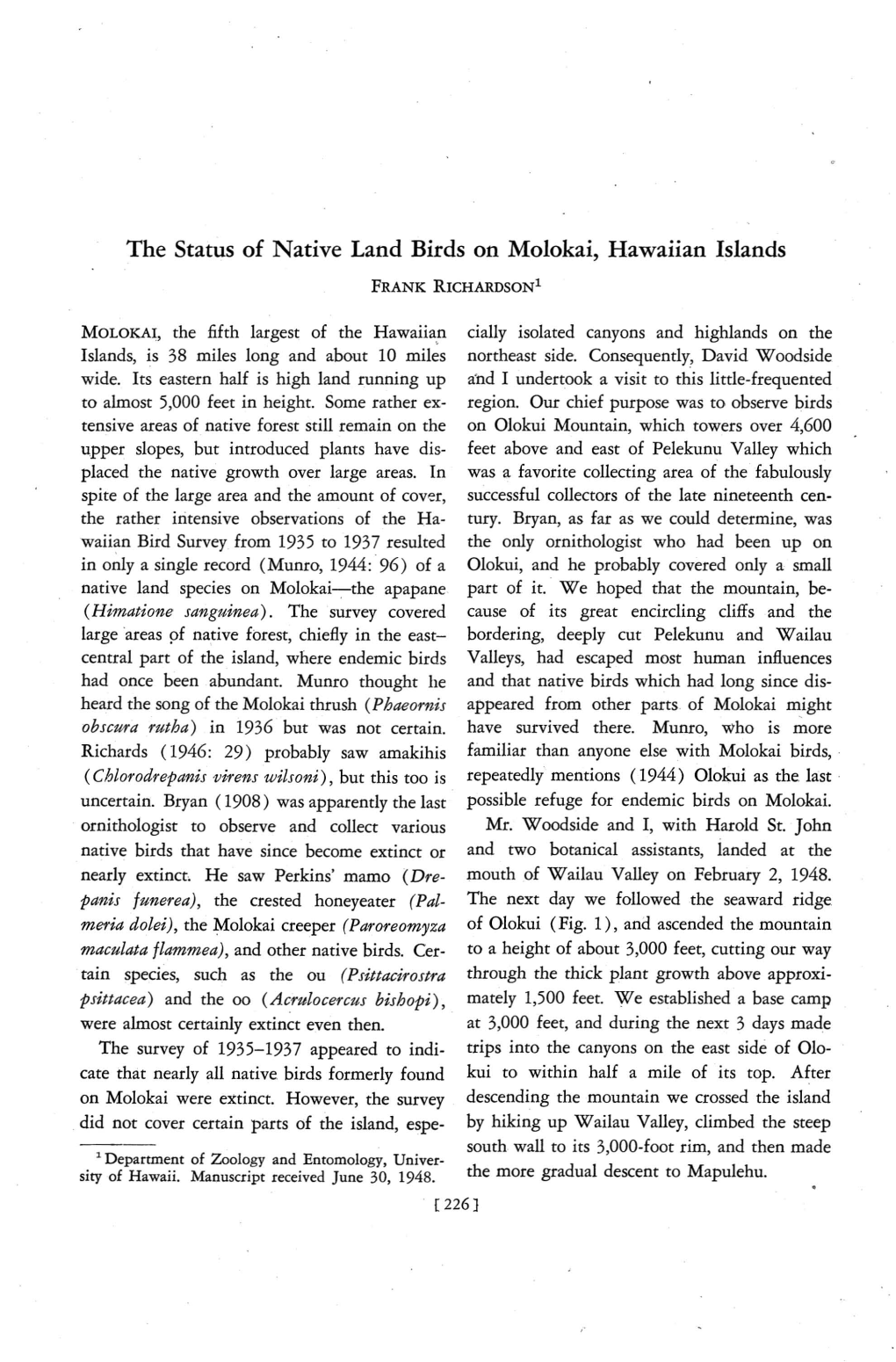

The Status of Native Land Birds on Molokai, Hawaiian Islands FRANK Richardsonl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hawaiian Island Environment

The Hawaiian Island Environment Item Type text; Article Authors Shlisky, Ayn Citation Shlisky, A. (2000). The Hawaiian Island environment. Rangelands, 22(5), 17-20. DOI 10.2458/azu_rangelands_v22i5_shlisky Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Rangelands Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 30/09/2021 01:33:31 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/639245 October 2000 17 The Hawaiian Island Environment Ayn Shlisky aradise: the universal vision we Each island is the result of accumula- most of their moisture. The driest areas have of Hawai‘i. Hawai‘i’s habi- tions of successive volcanic eruptions at are the upper slopes of high mountains, Ptats are diverse, unique, and love- the Hawaiian hot spot. The older volca- where a trade wind inversion tends to ly—a land of flowing red-hot lava, and noes have been transported from the suppress vertical lifting of air, or in lee- at the same time, delicate pastel orchids. Hawaiian hot spot to the northwest by ward positions at the coast or inland. Yet the Hawai‘i of today is much plate movement. Through time, they Winter cold fronts moving in from the changed from that discovered by the erode and subside to become a mere northwest may infrequently travel far Polynesians, or more than 1,000 years pinnacle of rock, then an atoll of accu- enough south to drop snow on the upper later, by Captain Cook. Over time, mulated coral, and finally a submerged slopes of Haleakala (Maui), Mauna Loa Hawai‘i has been discovered and re-dis- guyot (flat, reef-capped volcano) and Mauna Kea (Hawai‘i). -

State of Hawaii Community Health Needs Assessment

State of Hawaii Community Health Needs Assessment February 28, 2013 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Approach ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Data Sources and Methods ........................................................................................................................... 4 Areas of Need ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Selected Priority Areas ................................................................................................................................. 6 Note to the Reader ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Summary of CHNA Report Objectives and context ............................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Healthcare Association of Hawaii ................................................................................................ -

Hibiscus Arnottianus Subsp. Immaculatus (Koki‘O Ke‘Oke‘O) Current Classification: Endangered

5-YEAR REVIEW Short Form Summary Species Reviewed: Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. immaculatus (koki‘o ke‘oke‘o) Current Classification: Endangered Federal Register Notice announcing initiation of this review: [USFWS] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; initiation of 5-year reviews of 103 species in Hawaii. Federal Register 74(49):11130-11133. Lead Region/Field Office: Region 1/Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office (PIFWO), Honolulu, Hawaii Name of Reviewer(s): Marie Bruegmann, Plant Recovery Coordinator, PIFWO Jess Newton, Recovery Program Lead, PIFWO Assistant Field Supervisor for Endangered Species, PIFWO Methodology used to complete this 5-year review: This review was conducted by staff of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), beginning on March 16, 2009. The review was based on final critical habitat designations for Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. immaculatus and other species from the island of Molokai (USFWS 2003) as well as a review of current, available information. The National Tropical Botanical Garden provided an initial draft of portions of the review and recommendations for conservation actions needed prior to the next five-year review. The evaluation of Samuel Aruch, biological consultant, was reviewed by the Plant Recovery Coordinator. The document was then reviewed by the Recovery Program Lead and the Assistant Field Supervisor for Endangered Species before submission to the Field Supervisor for approval. Background: For information regarding the species listing history and other facts, please refer to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Environmental Conservation On-line System (ECOS) database for threatened and endangered species (http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public). -

Albatross Or Mōlī (Phoebastria Immutabilis) Black-Footed Albatross Or Ka’Upu (Phoebastria Nigripes) Short-Tailed Albatross (Phoebastria Albatrus)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Laysan Albatross or Mōlī (Phoebastria immutabilis) Black-footed Albatross or Ka’upu (Phoebastria nigripes) Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) Synopsis: These three North Pacific albatrosses are demographically similar, share vast oceanic ranges, and face similar threats. Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses nest primarily in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, while the Short-tailed Albatross nests mainly on islands near Japan but forages extensively in U.S. waters. The Short-tailed Albatross was once thought to be extinct but its population has been growing steadily since it was rediscovered in 1951 and now numbers over 3,000 birds. The Laysan is the most numerous albatross species in the world with a population over 1.5 million, but its trend has been hard to determine because of fluctuations in number of breeding pairs. The Black-footed Albatross is one-tenth as numerous as the Laysan and its trend also has been difficult to determine. Fisheries bycatch caused unsustainable mortality of adults in all three species but has been greatly reduced in the past 10-20 years. Climate change and sea level rise are perhaps the greatest long-term threat to Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses because their largest colonies are on low-lying atolls. Protecting and creating colonies on higher islands and managing non-native predators and human conflicts may become keys to their survival. Laysan, Black-footed, and Short-tailed Albatrosses (left to right), Midway. Photos Eric VanderWerf Status -

M U It I Resou Rce Forest Statistics for Molokai, Hawaii

United States Department of Agriculture Mu It iresou rce Forest Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Statistics for Resource Bulletin PNW-136 June 1986 Molokai, Hawaii Michael G. Buck, Patrick G. Costales, and Katharine McDuffie This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Authors MICHAEL G. BUCK and PATRICK G. COSIALLS are resource evaluation foresters with the Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wild- life in Honolulu, Hawaii. KATHARINE MCDUFFlt is a computer programmer/analyst at the Pacific Northwest Research Sta- tion, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, Oregon 97208. Abstract Summary Buck, Michael G.; Costales, Patrick G.; lhe island of Molokai, Hawaii, totals McDuf f ie, Katharine. Mu1 t i resource 163,211 acres, of which an estimated forest statistics for Molokai, Hawaii. 57,598 acres are forested --23,494 acres Resour. Bull. PNW-136. Portland, OR: classified as timberland and 34,104 acres U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest as other forest land. Previous inven- Service, Pacific Northwest Research tories show an additional estimated Station; 1986. 18 p. growing-stock volume of 4.2 million cubic feet on forest plantations, and an esti- This report summarizes a 1983 multire- mated total volume of 5.5 million cubic source forest inventory of the island of feet of a fuel-producing species growing Molokai, Hawaii. lables of forest area, on other forest land. Erosion occurs on timber volume, vegetation type, owner- only 7 percent of the island, the major- ship, land class, and wildlife are ity (85 percent) outside the forest re- presented. -

JAPANESE BUSH-WARBLER Cettia Diphone

JAPANESE BUSH-WARBLER Cettia diphone Other: Bush Warbler, Uguisu C. d. cantans? naturalized (non-native) resident, long established The Japanese Bush Warbler is native to Japan and surrounding islands, with northern populations being slightly migratory (AOU 1998). It and the Chinese or Manchurian bush-warbler (C. canturians) of e. China are closely related and sometimes considered conspecific (as "Bush Warbler"). Japanese Bush-Warblers have not been introduced anywhere in the world except the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands, where they were released on O'ahu in 1929-1941 (Caum 1933, Long 1981, Lever 1987) and have since spread naturally to most or all other Southeastern Islands. Concerns have been expressed about competition of bush-warblers for food with native species (Foster 2009). Japanese Bush-Warblers were initially introduced by the HBAF in 1929 to control insects, but several other releases on O'ahu (totaling approximately 138 individuals) were made by the Honolulu Mejiro Club and Hui Manu Society for aesthetic purposes, primarily or entirely in Nu'uanu Valley in 1931-1941 (Caum 1933; HAS 1967; Swedberg 1967a; Berger 1972, 1975c, 1981; E 17:2-3, 37:148; PoP 49[12]:29). They spread quickly on O'ahu, were noted by Munro (1944) in the Waianae Range by 1935, were considered established by Bryan (1941), were found commonly throughout both this and the Ko'olau Range by the 1950s (Northwood 1940, Pedley 1949; E 1[12]:3-4, 17:2-3, 25:91, 27:15-16, 31:108; summarized by Berger 1975c, Shallenberger 1977c, Shallenberger and Vaughn 1978), and were observed as far as Kahuku by 1977 (E 38:56). -

SAB 009 1986 P15-32 Study Areas.Pdf

HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS 15 FIGURE 9. Study areas on the island of Hawaii STUDY AREAS forests (Figs. 9 and 16). Most rainfall is derived from We established seven study areas on Hawaii (Fig. 9): a large horizontal vortex wind pattern, but rainfall dis- Kau, an isolated montane rainforest of ohia and koa tribution resembles the convection cell pattern of pre- on the southeast slopes of Mauna Loa; Hamakua, the cipitation. The top boundary of the study area lies near windward montane rainforest of ohia and koa on Mauna the inversion layer in dry alpine scrub. Below this is Kea and Mauna Loa; Puna, the low elevation ohia well-developed wet native forest (Fig. 17). Areas de- rainforest on Kilauea; Kipukas, a high elevation dry voted to sugar cane, macadamia nuts, and cattle border scrub area on the windward side with scattered pockets the study area below and laterally. of mesic forest; Kona, the diverse leeward montane The Kau study area is relatively undisturbed by hu- area on Mauna Loa and Hualalai; Mauna Kea, the man activity, as reflected in the closed canopy cover subalpine mamane-naio woodland on Mauna Kea; and (Fig. 18). Decreasing canopy cover at higher elevations Kohala, an isolated lower elevation ohia rainforest on marks the transition to subalpine scrublands. No sta- the northern end of the island. tion had more than 20% cover of introduced trees, We established two study areas on Maui, and one introduced shrubs, or passiflora. Koa-ohia forest is the each on Molokai, Lanai, and Kauai (Figs. 10-l 1). These dominant habitat in the northeast half of the study areas are mostly in montane ohia rainforests, although area, and ohia forest elsewhere. -

The History of Mammal Eradications in Hawai`I and the United States Associated Islands of the Central Pacific

Hess, S.C.; and J.D. Jacobi. The history of mammal eradications in Hawai`i and the United States associated islands of the Central Pacific The history of mammal eradications in Hawai`i and the United States associated islands of the Central Pacific S.C. Hess1 and J.D. Jacobi2 1U.S. Geological Survey Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, P.O. Box 44, Kīlauea Field Station, Hawai`i National Park, HI, 96718, USA. <[email protected]>. 2U.S. Geological Survey Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, 677 Ala Moana Blvd., Suite 615, Honolulu, HI, 96813, USA. Abstract Many eradications of mammal taxa have been accomplished on United States associated islands of the Central Pacific, beginning in 1910. Commonly eradicated species are rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), rats (Rattus spp.), feral cats (Felis catus), and several feral ungulates from smaller islands and fenced natural areas on larger Hawaiian Islands. Vegetation and avifauna have demonstrated dramatic recovery as a direct result of eradications. Techniques of worldwide significance, including the Judas goat method, were refined during these actions. The land area from which ungulates have been eradicated on large Hawaiian Islands is now greater than the total land area of some smaller Hawaiian Islands. Large multi-tenure islands present the greatest challenge to eradication because of conflicting societal interests regarding introduced mammals, mainly sustained-yield hunting. The difficulty of preventing reinvasion poses a persistent threat after eradication, particularly for feral pigs (Sus scrofa) on multi-tenure islands. Larger areas and more challenging species are now under consideration for eradication. The recovery of endangered Hawaiian birds may depend on the creation of large predator-proof exclosures on some of the larger islands. -

Laysan and Black-Footed Albatross Nesting Pairs at All Known Breeding Sites (Data from USFWS Unpublished Data Except As Noted Below)

A Conservation Action Plan for Black-footed Albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) and Laysan Albatross (P. immutabilis) Photograph by Marc D. Romano, USFWS Version 1.0 Contributors This Conservation Action Plan was compiled by Maura B. Naughton, Marc D. Romano and Tara S. Zimmerman, but it could not have been accomplished without the guidance, support, and input of the workshop participants and additional contributors that assisted with the development and review of this plan. Contributors included Joe Arceneaux, Greg Balogh, Jeremy Bisson, Louise Blight, John Burger, John Cusick, Kim Dietrich, Ann Edwards, Lyle Enriquez, Myra Finkelstein, Shannon Fitzgerald, Elizabeth Flint, Holly Freifeld, Eric Gilman, Tom Goode, Aaron Hebshi, Burr Heneman, Bill Henry, Michelle Hester, Jenny Hoskins, David Hyrenbach, Bill Kendall, Irene Kinan-Kelly, John Klavitter, Kathy Kuletz, Rebecca Lewison, James Ludwig, Ed Melvin, Ken Morgan, Mark Ono, Jayme Patrick, Kim Rivera, Scott Shaffer, Paul Sievert, David Smith, Jo Smith, Rob Suryan, Yonat Swimmer, Cynthia Vanderlip, Lewis VanFossen, Christine Volinski, Bill Wilson, Lee Ann Woodward, Lindsay Young, Stephanie Zador, Brenda Zaun, Michele Zwartjes. This version also benefited from the review and comments of Shelia Conant, John Croxall, Jaap Eijzenga, Falk Huettman, Mark Seamans, Ben Sullivan, and Jennifer Wheeler. Michelle Kappes and Scott Shaffer graciously provided access to unpublished data. Recommended Citation Naughton, M. B, M. D. Romano, T. S. Zimmerman. 2007. A Conservation Action Plan for Black-footed -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Friday, April 5, 2002 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revised Determinations of Prudency and Proposed Designations of Critical Habitat for Plant Species From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<13>2002 12:44 Apr 04, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\05APP2.SGM pfrm03 PsN: 05APP2 16492 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 66 / Friday, April 5, 2002 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR the threats from vandalism or collection materials concerning this proposal by of this species on Molokai. any one of several methods: Fish and Wildlife Service We propose critical habitat You may submit written comments designations for 46 species within 10 and information to the Field Supervisor, 50 CFR Part 17 critical habitat units totaling U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific RIN 1018–AH08 approximately 17,614 hectares (ha) Islands Office, 300 Ala Moana Blvd., (43,532 acres (ac)) on the island of Room 3–122, P.O. Box 50088, Honolulu, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Molokai. HI 96850–0001. and Plants; Revised Determinations of If this proposal is made final, section Prudency and Proposed Designations 7 of the Act requires Federal agencies to You may hand-deliver written of Critical Habitat for Plant Species ensure that actions they carry out, fund, comments to our Pacific Islands Office From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii or authorize do not destroy or adversely at the address given above. modify critical habitat to the extent that You may view comments and AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, the action appreciably diminishes the materials received, as well as supporting Interior. -

Narrative 05.01 Great Circle Distances Between

Table Number Table Name (Click on the table number to go to corresponding table) Narrative 05.01 Great Circle Distances Between Specified Places 05.02 Latitudes and Longitudes of Selected Places 05.03 Time Differences Between Honolulu and Selected Cities 05.04 Widths and Depths of Channels 05.05 General Coastline and Tidal Shoreline of Counties and Islands 05.06 Land and Water Area within the Fishery Conservation Zone 05.07 Land Area of Counties: 2000 05.08 Land Area of Islands: 2000 05.09 Major and Minor Islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago 05.10 Area and Depth of Selected Craters 05.11 Elevations of Major Summits 05.12 Major Named Waterfalls, by Islands 05.13 Major Streams, by Islands 05.14 Lakes and Lake-Like Waters, by Islands 05.15 Length and Width of Selected Beaches 05.16 Miscellaneous Geographic Statistics, by Island 05.17 Volcanic Eruptions: Mauna Loa 1950 to 1984, Kilauea 1969 to 2005 05.18 Major Earthquakes: 1838 to 2004 05.19 Earthquakes with Intensities on Oahu of V or Greater: 1859 to 2004 05.20 Tsunamis with Run-up of 2 Meters (6.6 feet) or More: 1819 to 2005 05.21 Major Dams 05.22 Fresh Water Use, by Type, by Counties: 2000 05.23 Water Services and Consumption, for County Waterworks: 2003 to 2005 05.24 Water Withdrawals by Source and Major Use, for the United States and Hawaii: 2000 05.25 Top 25 Water Users on Oahu: May 2004 to April 2005 05.26 Hazardous Waste Sites, Threats and Contaminants on Oahu 05.27 Toxic Chemical Releases in 2003, Hazardous Waste Sites in 2004, and Hazardous Waste Generated, Shipped, and Received -

Hawaiian Forest Birds CAMP 1992.Pdf

HA WAI'IAN FOREST BIRDS CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Final Report Compiled and Edited by S. Ellis, C. Kuehler, R. Lacy, K. Hughes, and U.S. Seal Produced by Participants of the Hawai'ian Forest Birds Conservation Assessment and Management Plan Workshop held 7-12 December 1992 Hilo, Hawaii A Publication of the Captive Breeding Specialist Group IUCN-The World Conservation Union I Species Survival Commission in partial fulfillment of USFWS Grant No. 14-48-0001-925926 u.s. FISU &WILDUFE SERVICE ~~\~4or~<>T~..:.'" The work of the Captive Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council: Conservators ($10,000 and above) Stewards ($500- $999) continued) Australian Species Management Program Banham Zoo Chicago Zoological Society Copenhagen Zoo Colombus Zoological Gardens Dutch Federation of Zoological Gardens Denver Zoological Foundation Erie Zoological Park Fossil Rim Wildlife Center Fota Wildlife Park Friends of Zoo Atlanta Givskud Zoo Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association Granby Zoological Society International Union of Di...-ectors of Zoological Gardens Howlet'"LS & Port Lympne Foundation Jacksonville Zoological Parle Knoxville Zoo Lubee Foundation National Geographic Magazine Metropolitan Toronto Zoo National Zoological Parlcs Board of South Africa Minnesota Zoological Garden Odense Zoo New York Zoological Society Orana Park Wildlife Trust Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo Paradise Park Saint Louis Zoo Porter Charitable Trust White Oak Plantation