The UK and Nuclear Reprocessing: Beating a Retreat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand

A Joint Report by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: − to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; − to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and − to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14 December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). -

Endless Trouble: Britain's Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant

Endless Trouble Britain’s Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP) Martin Forwood, Gordon MacKerron and William Walker Research Report No. 19 International Panel on Fissile Materials Endless Trouble: Britain’s Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP) © 2019 International Panel on Fissile Materials This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License To view a copy of this license, visit ww.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 On the cover: the world map shows in highlight the United Kingdom, site of THORP Dedication For Martin Forwood (1940–2019) Distinguished colleague and dear friend Table of Contents About the IPFM 1 Introduction 2 THORP: An Operational History 4 THORP: A Political History 11 THORP: A Chronology 1974 to 2018 21 Endnotes 26 About the authors 29 About the IPFM The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) was founded in January 2006 and is an independent group of arms control and nonproliferation experts from both nuclear- weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states. The mission of the IPFM is to analyze the technical basis for practical and achievable pol- icy initiatives to secure, consolidate, and reduce stockpiles of highly enriched uranium and plutonium. These fissile materials are the key ingredients in nuclear weapons, and their control is critical to achieving nuclear disarmament, to halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and to ensuring that terrorists do not acquire nuclear weapons. Both military and civilian stocks of fissile materials have to be addressed. The nuclear- weapon states still have enough fissile materials in their weapon stockpiles for tens of thousands of nuclear weapons. On the civilian side, enough plutonium has been sepa- rated to make a similarly large number of weapons. -

Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects

IAEA-TECDOC-1529 Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects February 2007 IAEA-TECDOC-1529 Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects February 2007 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Nuclear Fuel Cycle and Materials Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria MANAGEMENT OF REPROCESSED URANIUM IAEA, VIENNA, 2007 IAEA-TECDOC-1529 ISBN 92–0–114506–3 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2007 Printed by the IAEA in Austria February 2007 FOREWORD The International Atomic Energy Agency is giving continuous attention to the collection, analysis and exchange of information on issues of back-end of the nuclear fuel cycle, an important part of the nuclear fuel cycle. Reprocessing of spent fuel arising from nuclear power production is one of the strategies for the back end of the fuel cycle. As a major fraction of spent fuel is made up of uranium, chemical reprocessing of spent fuel would leave behind large quantities of separated uranium which is designated as reprocessed uranium (RepU). Reprocessing of spent fuel could form a crucial part of future fuel cycle methodologies, which currently aim to separate and recover plutonium and minor actinides. The use of reprocessed uranium (RepU) and plutonium reduces the overall environmental impact of the entire fuel cycle. Environmental considerations will be important in determining the future growth of nuclear energy. It should be emphasized that the recycling of fissile materials not only reduces the toxicity and volumes of waste from the back end of the fuel cycle; it also reduces requirements for fresh milling and mill tailings. -

Background, Status and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities

NUREG-1909 Background, Status, and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities ACNW&M White Paper Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials NUREG-1909 Background, Status, and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities ACNW&M White Paper Manuscript Completed: May 2008 Date Published: June 2008 Prepared by A.G. Croff, R.G. Wymer, L.L. Tavlarides, J.H. Flack, H.G. Larson Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials THIS PAGE WAS LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY ii ABSTRACT In February 2006, the Commission directed the Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials (ACNW&M) to remain abreast of developments in the area of spent nuclear fuel reprocessing, and to be ready to provide advice should the need arise. A white paper was prepared in response to that direction and focuses on three major areas: (1) historical approaches to development, design, and operation of spent nuclear fuel recycle facilities, (2) recent advances in spent nuclear fuel recycle technologies, and (3) technical and regulatory issues that will need to be addressed if advanced spent nuclear fuel recycle is to be implemented. This white paper was sent to the Commission by the ACNW&M as an attachment to a letter dated October 11, 2007 (ML072840119). In addition to being useful to the ACNW&M in advising the Commission, the authors believe that the white paper could be useful to a broad audience, including the NRC staff, the U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, and other organizations interested in understanding the nuclear fuel cycle. -

Nuclear Fuel Cycle Information System

IAEA-TECDOC-1613 Nuclear Fuel Cycle Information System A Directory of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities 2009 Edition April 2009 IAEA-TECDOC-1613 Nuclear Fuel Cycle Information System A Directory of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities 2009 Edition April 2009 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Nuclear Fuel Cycle and Materials Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria NUCLEAR FUEL CYCLE INFORMATION SYSTEM: A DIRECTORY OF NUCLEAR FUEL CYCLE FACILITIES 2009 EDITION IAEA, VIENNA, 2009 ISBN 978–92–0–102109–0 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2009 Printed by the IAEA in Austria April 2009 FOREWORD In recent years, there have been rising expectations for nuclear power all over the world to meet the ever increasing demand for electricity. Several countries with nuclear power have declared intentions to build new nuclear power plants to replace their existing capacities or to add new capacities. Several other countries without nuclear power are taking an active interest in launching nuclear power programmes. Nuclear power and nuclear fuel cycle go hand in hand. Hence implementations of such nuclear power programmes cannot be considered without parallel development in the nuclear fuel cycle area. The worldwide nuclear fuel cycle industry comprises several global players which are operating on a commercial basis in more than one country and many other domestic players which are active only in their respective countries. Knowing the current status and the future outlook of the nuclear fuel cycle industry is important not only for meeting the needs of global nuclear power development but also for facilitating the multilateral approach to the nuclear fuel cycle currently being discussed with a focus on ‘assurance of fuel supply’ and ‘non-proliferation of nuclear materials’. -

Global Fissile Material Report 2015 Nuclear Weapon and Fissile Material Stockpiles and Production

Global Fissile Material Report 2015 Nuclear Weapon and Fissile Material Stockpiles and Production Eighth annual report of the International Panel on Fissile Materials Eighth annual report of the International Panel on Fissile Materials Global Fissile Material Report 2015 Nuclear Weapon and Fissile Material Stockpiles and Production 2015 International Panel on Fissile Materials This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License To view a copy of this license, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 On the cover: the map shows existing uranium enrichment and plutonium separation (reprocessing) facilities. Table of Contents About the IPFM 1 Summary 2 Nuclear Weapons 4 Highly Enriched Uranium 10 Military HEU 13 Civilian Use of HEU 17 Civilian Uranium Enrichment Plants 19 Separated Plutonium 23 Weapons Plutonium 25 Civilian Plutonium 29 Nuclear Weapons, Fissile Materials and Transparency 34 Appendix 1. Fissile Materials and Nuclear Weapons 40 Appendix 2. Uranium Enrichment Plants 48 Appendix 3. Reprocessing Plants 49 Appendix 4. Civilian Plutonium Stockpile Declarations 50 Endnotes 51 About the IPFM The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) was founded in January 2006. It is an independent group of arms-control and nonproliferation experts from seventeen countries, including both nuclear weapon and non-nuclear weapon states. The mission of the IPFM is to analyze the technical basis for practical and achievable policy initiatives to secure, consolidate, and reduce stockpiles of highly enriched urani- um and plutonium. These fissile materials are the key ingredients in nuclear weapons, and their control is critical to nuclear disarmament, halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and ensuring that terrorists do not acquire nuclear weapons. -

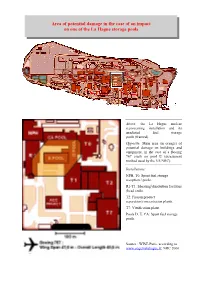

Area of Potential Damage in the Case of an Impact on One of the La Hague Storage Pools

Area of potential damage in the case of an impact on one of the La Hague storage pools Above: the La Hague nuclear reprocessing installation and its irradiated fuel storage pools (framed). Opposite: Main area (in orange) of potential damage on buildings and equipment, in the case of a Boeing 767 crash on pool E (assessment method used by the US NRC). Installations: NPH, T0: Spent fuel storage reception / pools. R1-T1: Shearing/dissolution facilities (head ends). T2: Fission product separation/concentration plants. T7: Vitrification plant. Pools D, E, CA: Spent fuel storage pools. Source : WISE-Paris, according to www.cogemalahague.fr, NRC 2000 Presentation of the Sellafield reprocessing facilities Sea Discharge B302 & B302.1 Pipelines Plutonium Main Gate stores B205 Magnox N Reprocessing B204. Old Reprocessing Railway Plant Ssidings B33 MOX Demonstration Facility Windscale Piles EARP Waste Treatment Complex High Level THORP Waste Tanks Ponds Calder Hall Magnox Reactors 1-4 B570 THORP B311 Fuel Handling Plant B355 Waste B572 Encapsulation Vitrificcation plants MOX Plant Plant Source : BNFL Area of potential damage in the case of an impact on Sellafield B215 liquid high level waste storage Source: WISE-Paris according to NRC 20001, based on a map transmitted by BNFL 1 US NRC, « Study of Spent Fuel Pool Accident Risk at Decommissioning Nuclear Power Plants », October 2000. Transports of German Plutonium in France Fabrication/assembling of MOX Fuel Mol/Dessel MOX Reprocessing ) ce ? an u Plutonium Separation Fr f P n r o (i ea ar m t/y e k ,1 t/y 00 : 0 5 ps ,4 GERMANY ra -1 sc : 1 on r La Hague ati e ric d Nuclear fab w 40 km X po O u Valognes ? M P 850 km Power Plants Irradiated fuel assemblies m u i 9 n 00 o k t m u l p f o Pu ? p r M o a w e O d X e y f r ) / a t : e br 2 i c c ,7 5 a , ti t/ n o y a 2 n e r s a . -

Back-End of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle (FC) Is One of Key Problems of Nuclear Power As a Whole

International Atomic Energy Agency Status and Prospects of Advanced Nuclear Fuel Cycles Alexander Bychkov DDG-NE INPRO Dialogue Forum “Drivers and Impediments for Regional Cooperation on the Way to Sustainable Nuclear Energy Systems” July 30 – August 3, 2012, Vienna International Atomic Energy Agency Nuclear Fuel Cycle International Atomic Energy Agency Main issues • Assurance of Supply for Nuclear Fuel • Spent Fuel Management Options • Spent Fuel Storage • Spent Fuel Direct Disposal • Spent Fuel Recycling International Atomic Energy Agency Assurance of Supply for Nuclear Fuel The principles of assurance of supply In implementing assurance of supply and future related mechanisms, the basic principles are: • The LEU would be available for all eligible IAEA Member States wishing to continue or introduce civil nuclear power programmes; • The supply mechanism is entirely voluntary and shall not distort the functioning of the commercial market but rather reinforce existing market mechanisms. It should neither have any disadvantages for those States which choose not to join the mechanism; and • The rights of Member States, including establishing or expanding their own production capacity in the nuclear fuel cycle, shall remain intact and shall not in any way be compromised or diminished by the establishment of international assurance of supply mechanisms. International Atomic Energy Agency Assurance of Supply for Nuclear Fuel Current activities Efforts to establish mechanisms to ensure that countries can be confident of a assure fuel supply have progressed in several fronts. The most advanced proposals for an additional level of assurance for the front end of the fuel cycle are: • The IAEA LEU bank; • The UK-lead Nuclear Fuel Assurance (NFA); • The guaranteed LEU reserve (a physical reserve of LEU and the supply of the LEU therefrom to the IAEA and its Member States in Angarsk); • The International Uranium Enrichment Centre (IUEC) in Angarsk; and • The Multinational Enrichment Sanctuary Project (MESP). -

The Safety of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Cov-Safety Nuclear FuelCyc 3588 10/10/05 16:04 Page 1 Nuclear Safety The Safety of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle NUCLEAR•ENERGY•AGENCY Nuclear Safety The Safety of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Third edition © OECD 2005 NEA No. 3588 NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation’s statistics gathering and research on economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines and standards agreed by its members. * * * This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Use of Reprocessed Uranium

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NF-T-4.4 Basic Use of Reprocessed Principles Uranium: Challenges and Options Objectives Guides Technical Reports INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA ISBN 978–92–0–106409–7 ISSN 1995–7807 P1411_cover.indd 1 2009-12-23 09:13:14 IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES PUBLICATIONS STRUCTURE OF THE IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES Under the terms of Articles III.A and VIII.C of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to foster the exchange of scientific and technical information on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. The publications in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series provide information in the areas of nuclear power, nuclear fuel cycle, radioactive waste management and decommissioning, and on general issues that are relevant to all of the above mentioned areas. The structure of the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series comprises three levels: 1 — Basic Principles and Objectives; 2 — Guides; and 3 — Technical Reports. The Nuclear Energy Basic Principles publication describes the rationale and vision for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Objectives publications explain the expectations to be met in various areas at different stages of implementation. Nuclear Energy Series Guides provide high level guidance on how to achieve the objectives related to the various topics and areas involving the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Technical Reports provide additional, more detailed, information on activities related to the various areas dealt with in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series. The IAEA Nuclear Energy Series publications are coded as follows: NG — general; NP — nuclear power; NF — nuclear fuel; NW — radioactive waste management and decommissioning. -

The Plutonium Business

WALTER C. PATTERSON for the Nuclear Control Institute The Plutonium Business and the Spread of the Bomb Granada Publishing 1 Paladin Books Granada Publishing Ltd 8 Grafton Street, London WIX MA Published by Paladin Books 1984 Copyright Nuclear Control Institute 1984 ISBN 0-586-08482-7 Reproduced, printed and bound in Great Britain by Hazell Watson & Viney Limited, Aylesbury, Bucks Set in Ehrhardt All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re- sold , hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Walter C. Patterson was born in Canada in 1936. He took a postgraduate degree in nuclear physics at the University of Manitoba. In 1960 he moved to Britain, where he became involved in environmental issues. He joined the staff of Friends of the Earth in London in 1972, was their energy specialist until 1978 and was their lead witness at the Windscale Inquiry. Since 1978 he has been an independent commentator and consultant, dealing with energy and nuclear policy issues. He is energy consultant to Friends of the Earth, and was a witness at the Sizewell Inquiry. -

THE WORLD NUCLEAR WASTE REPORT 2019 Focus Europe. PARTNERS & SPONSORS

THE WORLD NUCLEAR WASTE REPORT 2019 Focus Europe. PARTNERS & SPONSORS Bürgerinitiative Umweltschutz Lüchow-Dannenberg This report would have not been possible without the generous support of a diverse group of friends and partners, in particular – listed in alphabetical order – the Altner-Combecher Stiftung, Bäuerliche Notgemeinschaft Trebel, Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz (BUND), Bürgerinitiative Umweltschutz Lüchow-Dannenberg e.V., Climate Core and Green/EFA MEPs Group in the European Parliament, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (HBS) and its offices in Berlin, Brussels, Paris, Prague, and Washington DC, KLAR! Schweiz, Annette und Wolf Römmig, and the Swiss Energy Foundation. Thank you all for making this possible! THE WORLD NUCLEAR WASTE REPORT — 2019 3 FOREWORD More than 40 years ago in my home region, the forest near the village of Gorleben was chosen as the location for the German National Nuclear Waste Disposal Center. The site, which is now at the country’s center but at the time was located directly on the border between East and West Germany, was meant to host all facilities for reprocessing, treatment, storage, and a deep geological repository. The company responsible (which has long since closed) intended to open the repository for spent fuel in the salt dome named Gorleben-Rambow in 1999. After Fukushima, the German government decided to phase out nuclear energy for the second time. The experience of the nuclear catastrophe in Japan in 2011 also set in motion the review of the plans for the repository at Gorleben. After around 40 years of debating and fighting over Gorleben, the German government and parliament decided in favor of a new participatory site selection process for the repos- itory for high-level nuclear waste.