Burnam on Sea Windfarm Decision Dated 15 January 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Brent Memories Fv3 0.Pdf

Contents 1 Earlier Days in East Brent by Ivor Punnett 3 East Brent 60 Years Ago by Grace Hudson 4 The Knoll Villages by Rosa Chivers 6 Brent Knoll Station by Rosa Chivers 7 Last Thatch at East Brent - Weston Mercury & Somersetshire Herald 8 East Brent in the 1920's and 1930's by Waiter Champion 9 A Musical Note by Freda Ham 9 A Journey Along Life's Path by Chrissie Strong 16 Childhood Memories of Old East Brent by Ruth Rider 19 East Brent Methodist Church by Grace Hudson 20 Random Recollections by Connle Hudson 25 Raise the Song of Harvest Home by Ronald Bailey 27 The First Harvest Home in East Brent by Ronald Bailey 30 'The Golden Age' at East Brent by John Bailey 32 Somerset Year Book, 1933 (extract) 33 Burnham Deanery Magazine (extracts, June and November 1929) 35 Acknowledgments 35 Index to Photographs 36-45 Photographs 46 Map of Brent Knoll 47 Map of East Brent Foreword It must have been about 1985 when we invited Chrissie Strong (nee Edwards) to have tea with us. She had been a family friend for many years having helped us in the house when we were children. She had a wonderfully retentive memory, and after she had been reminiscing about life in the village, we asked her to write down some of her memories. She was rather diffident about such an undertaking, but sometime afterwards we received a notebook through the post, containing her recollections. This was the start of the book. Chrissie's memories are not necessarily in chronological order, as they were random jottings, but we feel this in no way detracts from its interest. -

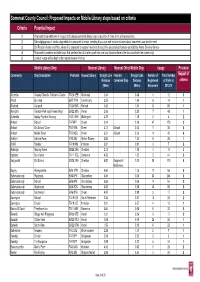

Consultation List of Mobile Stops and Potential Impact.Xlsx

Somerset County Council: Proposed Impacts on Mobile Library stops based on criteria Criteria Potential Impact 1 Proposed to be withdrawn in August 2015 because mobile library stop is less than 3 miles from a library building 2 School/playgroup or similar stop which it is proposed to retain, pending discussion with each institution about how needs can best be met 3 Old People's home or similar, where it is proposed to support residents through the personalised service provided by Home Delivery Service 4 Proposed to combine multiple stops that are less than 0.5 miles apart into one stop (location/time to be discussed with the community) 5 Level of usage will be kept under regular review in future Mobile Library Stop Nearest Library Nearest Other Mobile Stop Usage Potential Community Stop Description Postcode Nearest Library Straight Line Possible Straight Line Number of Total Number impact of Distance Combined Stop Distance Registered of Visits in criteria (Miles) (Miles) Borrowers 2013/14 Alcombe Cheeky Cherubs Children’s Centre TA24 5EB Minehead 0.64 0.38 1 12 2 Alford Bus stop BA7 7PWCastle Cary 2.05 1.44 6 19 1 Allerford Car park TA24 8HSPorlock 1.36 1.01 8 80 1 Alvington Fairacre Park (opp Fennel Way) BA22 8SA Yeovil 2.06 0.20 7 48 1 Ashbrittle Appley Pavillion Nursery TA21 0HH Wellington 4.22 1.18 2 4 2 Ashcott School TA79PP Street 3.04 0.18 47 179 2 Ashcott Old School Close TA7 9RA Street 3.12 Ashcott 0.13 11 35 4 Ashcott Middle Street TA7 9QG Street 3.01 Ashcott 0.13 14 45 4 Ashford Ashford Farm TA5 2NL Nether Stowey 2.86 1.10 6 -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS52117.TXT

M127-7 SEDGEMOOR DISTRICT COUNCIL CANDIDATES SUMMARY PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION - 3RD MAY 2007 Area Candidates Party Address Parish of Ashcott Adrian Scot Davis 20 School Hill, Ashcott, Somerset, DAVIS TA7 9PN Number of Seats : 8 Cilla Ann Thurlow Grain Ashcott Resident 3 Pedwell Lane, Ashcott, Bridgwater, GRAIN Somerset, TA7 9PD Joe Jenkins Saddle Stones, 31 Pedwell Hill, JENKINS Ashcott, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA7 9BD Jenny Lawrence 3 The Batch, Ashcott, Bridgwater, LAWRENCE Somerset, TA7 9PG Jack Miles Sayer 29 High Street, Ashcott, Bridgwater, SAYER TA7 9PZ Axbridge Town Council Dennis Bratt Past Mayor of Axbridge 62 Knightstone Close, Axbridge, BRATT Somerset, BS26 2DJ Number of Seats : 13 Kate Walker Independent 36 Houlgate Way, Axbridge, Somerset, Browne BS26 2BY BROWNE Christopher Byrne Wavering Down, Webbington Road, BYRNE Cross, Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2EL Jeremy Gall 6 Moorland St, Axbridge, BS26 2BA GALL Pauline Ann Ham 15 Hippisley Drive, Axbridge, HAM Somerset, BS26 2DE Barry Edward Hamblin 40 West Street, Axbridge, Somerset, HAMBLIN BS26 2AD Val Isaac Vine Cottage, 50 West Street, ISAAC Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2AD James A H Lukins Retired Farmer Townsend House, Axbridge LUKINS Andrew Robert Matthews The Cottage, Horns Lane, Axbridge, MATTHEWS Somerset, BS26 2AE Paul Leslie Passey Somerhayes, Jubilee Road, Axbridge, PASSEY Somerset, BS26 2DA Elizabeth Beryl Scott Moorland Farm, Axbridge, Somerset, SCOTT BS26 2BA Michael Taylor Mornington House, Compton Lane, TAYLOR Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2HP Jennifer Mary Trotman 4 Bailiff's -

Download Original Attachment

Properties over 30K Account................. Property................ Property.. Current. Holder Address Postcode RV Ashcott Primary School ASHCOTT PRIMARY SCHOOL TA7 9PP 30250 RIDGEWAY ASHCOTT BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Consumer Buyers Ltd T/a CHURCH FARM STATION ROAD TA7 9QP 42250 Living Homes ASHCOTT BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Butcombe Brewery Ltd THE LAMB INN THE SQUARE BS26 2AP 38000 AXBRIDGE SOMERSET Sustainable Drainage CLEARWATER HOUSE BS26 2RH 53500 System Ltd CASTLEMILLS BIDDISHAM AXBRIDGE SOMERSET The Environment Agency BRADNEY DEPOT BRADNEY TA7 8PQ 56500 LANE BAWDRIP BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Burnham & Berrow Golf BURNHAM & BERROW GOLF TA8 2PE 144000 Club Limited CLUB ST CHRISTOPHERS WAY BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Berrow Primary School BERROW PRIMARY SCHOOL TA8 2LJ 49750 RUGOSA DRIVE BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Brightholme Caravan Park BRIGHTHOLME CARAVAN PARK TA8 2QY 46250 Ltd COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET John Fowler Holidays SANDY GLADE HOLIDAY PARK TA8 2QR 236500 Limited COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Unity Farm Holiday HOLIDAY RESORT UNITY TA8 2QY 818500 Centre Ltd COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET The Caravan Club Limited THE CARAVAN CLUB HURN TA8 2QT 43100 LANE BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Flamingo Park Limited ANIMAL FARM COUNTRY PARK TA8 2RW 37500 RED ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Brean Down Caravan Park BREAN DOWN CARAVAN PARK TA8 2RS 47500 Ltd BREAN DOWN ROAD BREAN BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET A G Hicks Ltd NO 1 CARAVAN SITE TA8 2SF 71000 SOUTHFIELD FARM CHURCH ROAD BREAN BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET -

Brent Street, Brent Knoll £459,950

Brent Street, Brent Knoll £459,950 AN EXTENDED AND SUPERBLY MODERNISED DETACHED 3 BEDROOM BUNGALOW WITH THE BENEFIT OF GAS CENTRAL HEATING & DOUBLE GLAZING. OFFERED WITH NO ONWARD CHAIN. CONSUMER PROTECTION FROM UNFAIR TRADING REGULATIONS • FULLY RENOVATED • 3 DOUBLE BEDS (EN- • GARAGE & PARKING These details are for guidance only and complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. If there is any point, which is of particular importance, verification should be obtained. They do not constitute a contract or part of a contract. All measurements are approximate. No guarantees can be given with respect to planning permission or fitness of purpose. No apparatus, equipment, fixture or fitting has been tested. Items shown • GAS C/H & DBLE GLZ SUITE) • NO OWNARD CHAIN in photographs are NOT necessarily included. Interested parties are advised to check availability and make an appointment to view before travelling to see a property. • SUPERB, LEVEL GARDENS THE DATA PROTECTION ACT 1998 Please note that all personal provided by customers wishing to receive information and/or services from the estate agent will be processed by the estate agent. For further information about the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 see - http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/12277/contents/made A&F Property Group Tel: 01278 78 22 66 18 College Street Fax: 01278 79 21 23 www.aandfproperty.co.uk 01278 78 22 66 Burnham on Sea www.aandfproperty.co.uk [email protected] 01278 79 21 23 Somerset, TA8 1AE [email protected] stainless steel sink unit with mixer tap. Range The Southerly facing front garden with Summerfield, 16 Brent Street, Brent Knoll, Somerset, TA9 4DU of matching base, drawer and wall mounted panelled open slatted fencing comprises 2 units (1 housing the "Baxi" gas combination sections of lawn, holly bushes and 2 DESCRIPTION: glass double glazed side panels. -

Oaklands Brent Knoll, Somerset Heating Throughout with Individual Thermostats Fitted to Each Oaklands Room, Controlled from a Central Panel

Oaklands Brent Knoll, Somerset heating throughout with individual thermostats fitted to each Oaklands room, controlled from a central panel. A computerised C-BUS Brent Knoll, Somerset lighting system is installed, television points in every room and provision has been made for ceiling speakers throughout. A distinctive oak framed property with grounds reaching up the The front door opens into a covered external hallway which slopes of Brent Knoll leads to the enclosed courtyard. To the left, there is a triple M5 (J 22) 3 miles Bristol 21 miles Weston-super-Mare 8 miles garage, while to the right is a study with slate floor and a door Wells 15 miles (distances approximate) that leads in to the house through the kitchen. The impressive open plan kitchen/dining/sitting room measures over 54ft in length creating a wonderful sense of Accommodation and amenities space with exposed oak beams, A-frames and large glass External entrance Study Outstanding open plan kitchen/ windows on display. Doors open to the tiled terrace with pond dining/sitting room Utility room Cloakroom Inner hall and views across the garden, paddock and woodland. 4 bedrooms 1 en suite bathroom 1 en suite shower room The bespoke hand painted kitchen includes integrated Family bathroom appliances predominately designed by Miele. These include a wine cooler, dishwasher, microwave, gas hob with extractor Triple garage Enclosed terrace Gardens and grounds hood, two double ovens and espresso coffee maker. There is also space for a large fridge freezer. Granite work surfaces, In all about 0.85 of an hectare (2.1 acres) double Belfast sink and two additional preparation sinks in the central island complete the kitchen. -

Somerset County Council District of Sedgemoor & Mendip Parishes Of

(Notice5) Somerset County Council District of Sedgemoor & Mendip Parishes of Brent Knoll, Lympsham,Wedmore, Rodney Stoke, Chapel Allerton, Cheddar, Brean and Weare Temporary Prohibition of Vehicles Somerset County Council in exercise of its powers under Section 14(1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 as amended and after giving notice to the Chief Officer of Police, hereby makes the following Order prohibiting all traffic from proceeding along the roads specified in the schedule to this Order:- This order will enable Gigaclear to carry out reinstatement works in this road. The Order became effective on 26th day of June 2018 and remains in force for eighteen months. While the closure is in operation an alternative route will be signed as detailed below. This Order is required to facilitate highway works and is necessary for the safety of the workforce whilst carrying out their duties. The restriction shall apply when indicated by traffic signs. Please visit www.roadworks.org for further information on the alternative route For information about the works being carried out please contact Telent Infrastructure Services on 0800 078 9200 Patrick Flaherty Chief Executive Dated: 14th November 2019 Schedule Temporary Prohibition of Vehicles Mill Lane, Mill Lane, Stone Allerton – from its junction with Notting Hill Way Stone Allerton to its junction with Allerton Sutton Road - Access to be maintained for residents -The proposed start date is 20th November 2019 for 3 days Statement of reasons for making the Order a) Because works are being or are proposed to be executed on or near the road; or b) because of the likelihood of danger to the public, or of serious damage to the road, which is not attributable to such works. -

^Econd Dag's Iptoceedings. on Wednesday Morning the Members

— Blcadon Chnrcli. 33 ^econD Dag’s iptoceeDings. On Wednesday morning the members left Grove Park in brakes for Bleadon, Axbridge, the Brents, and Brent Knoll Camp. The weather was very favourable, both on this day and throughout the Meeting. ISIealion Cfturcb. On leaving the brakes, the party inspected the Cross (figured in Pooley’s Crosses of Sornerset, p. 66) on the way up to the Church, where they were met by the Rector, the Rev. J. T. Langdale. Before entering the Church, Dr. F. J. Allen made the following remarks on the tower :~ “ This tower belongs to the leading type of the Mend ip dis- trict, namely, those having three windows abreast, —the triple window class. The principal towers of this class in the West Mendip district are those of Ban well and Winscombe, and this tower is a later and inferior derivative from their design. pecu-liar this The features of tower are ; (1) the diagonal but- tresses ; in all other related towers they are rectangular, at least in their lower part the situation of the staircase at ; (2) a corner; it is usually on one side, near a corner; (3) the great distance between the window-sill and the top string- course : the effect is better when they coincide.” The party then went into the church where the President, Lt.-Colonel J. R. Bramble, F.S.A., delivered the following- address : “ The church is said by Collinson to be dedicated to St. Peter, and this is followed in the Diocesan Kalendar. Weaver’s Somerset Incnmhents says SS. Peter'and Paul. -

35P FEBRUARY 2014

NT KN E OL R L B FEBRUARY 2014 35p LANZA HAIRCARE EST. 1994 HAIR BY DESIGN HAIR EXTENSION SPECIALISTS For the ultimate hairstyling experience we will make every clients visit unique, and work with you to create your own individual style. Sam is now offering RACOON HAIR EXTENSIONS, everything from simply refreshing your current style to developing a whole new image. Lisa, Rachael, Sam and Lauren thank all their existing clients for their continuous support. Hair by Design will be closed on Mondays A WARM WELCOME AWAITS ALL. Gift vouchers are available for all treatments The Pines, Brent Street, Brent Knoll Call us now on 01278 760 506 Please mention the Brent Knoll News when replying to adverts 3 The Parish of Three Saints St Christopher, Lympsham St Michael, Brent Knoll St Mary, East Brent BAPTISM WEDDING When do we hold baptisms? How do we book our wedding? - on the fourth or fifth Sunday of a month at - please contact our Parish Administrator in 12.15pm or 1.15pm; the Church Office, who will discuss with we normally have one family at each time, you availability of dates and times; will talk however, there may be occasions when we to you about the qualifying connection you have another child to baptise and so there have with the parish; and will take you and will be two families together; your fiancé’s details; - or at our regular worship on a Sunday - you will then be contacted by our vicar to morning at 10.00am; arrange a date to meet. There will be exceptions due to the church CHURCH OFFICE calendar Church Road, East Brent, TA9 4HZ How do you book a baptism? E-mail: [email protected] - collect an application form the Church Phone: 01278 769082 Office Open Tuesday & Wednesday, 10.30am-3.30pm Priest in Charge Revd. -

Brockley House, 115 Brent Street, Brent Knoll, Somerset Gth.Net Brockley House, 115 Brent Street Brent Knoll, Somerset TA9 4EH

Brockley House, 115 Brent Street, Brent Knoll, Somerset gth.net Brockley House, 115 Brent Street Brent Knoll, Somerset TA9 4EH Burnham on Sea 3 miles; Highbridge 3 miles; Weston super Mare 9 miles; M5 Junction 22 is 2 miles This extended, deceptively spacious 5 bedroom, 2 bathroom detached residence offers flexible and versatile accommodation together with attached offices (providing a superb ‘live/work’ opportunity), ample off road parking and attractive enclosed garden, offered with no onward chain. Guide Price £575,000 Description This 1960’s built extended detached property offers well maintained flexible accommodation comprising: entrance hallway, cloakroom/WC, 22 foot living room, 20 foot dining room, open plan stunning kitchen/breakfast room (with recently re-fitted bespoke kitchen with granite work surfaces), spacious utility room, attached office complex (with 2 separate offices, kitchenette area and further cloakroom/WC) on the ground floor. The first floor comprises 5 bedrooms (master has an en- suite and dressing area) and a modern family bathroom. Further benefits include gas central heating (boiler serviced annually), mostly UPVC double glazed windows, a surprising that to the rear of the new rear boundary fence our Vendor is amount of character features for a modern property and the retaining an area of garden on which he has obtained planning kitchen has been re-fitted with granite work surfaces, built-in consent to build a new 3 bed detached residence. No windows dishwasher and space for a range cooker. All fitted carpets and from the new residence will overlook the garden of Brockley blinds are set to remain. -

Brent Knoll & Berrow Sands 11.7 Miles Grade

Brent Knoll and Berrow Sands, Somerset Starts at Church Road, East Brent 5 hours 46 minutes | 11.7miles 18.8km | Moderate ID: 0.1462 | Developed by: Harvey Reynolds | Checked by: Edward Levy | www.ramblersroutes.org At the start of this walk you ascend Brent Knoll, from which height you can see the rest of the route, which heads to and from a stretch along Berrow Beach mostly via fields. This walk gets the hill (mostly) out of the way at the start. © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100033886 1000 m Scale = 1 : 54K 2000 ft Main Route Alternative Route Point of Interest Waypoint Distance: 18.72km Ascent: 165m Descent: 165m Route Profile 160 120 80 Height (m) Height 40 0 0.0 1.3 2.4 3.5 4.6 5.6 6.6 7.7 9.1 10.5 11.7 12.8 13.8 14.9 16.1 17.1 18.1 *move mouse over graph to see points on route The Ramblers is Britain’s walking charity. We work to safeguard the footpaths, countryside and other places where we all go walking. We encourage people to walk for their health and wellbeing. To become a member visit www.ramblers.org.uk Starts at Walk starts from the phone box at the end of Church Road, East Brent, Somerset Ends at Church Road, East Brent Getting there Arrive in East Brent on the B3140 Brent Road. Find a side street to park in East Brent, then walk to the telephone box to start the walk. -

Somerset. Axbridge

TlrRECTORY. ] SOMERSET. AXBRIDGE. 31 'The following places are included in the petty sessional Hutton, Kewstoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Markx division :-Axbridge, Badgwortb, Banwell, Berrow, Hutton, Kewstoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Biddisbam, Blagdon, !Bleadon, Brean, Brent Knoll, Burn Markx, Nyland-with-Batcombe, Puxton, Rowberrow, ;ham. Burnham Without, Burrington, Butcombe, Chapel Shipham, Uphill, Weare, Wedmore, Weston-super .AIle.:rton, Charterhouse (ville), Cheddar, Christon, Mare, Wick St. Lawrence, Winscombe, Worle, Wring 'Churchill, Compton Bishop, Congresbury, East Brent, ton-with-Broadfield. The population of the union in ;Highbrid-ge North, Highbridge South, Hutton, Kew 1891 was 43,189 and in 1901 was 47,915; area, 97,529; ·stoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Mark, Nyland & rateable value in 1897 was £234,387 'Batcombe, Puxton, Rowberrow, Shipbam, UphiIl,Weare, Cbairman of the Board of Guardians, C. H. Poole 'Wedmore, Weston-supe.:r-Mare, Wick St. Lawrence, Clerk to the Guardians & Assessment Committee, William 'Winscombe, Worle &; Wrington Reece, West street, Axbridge AXBRIDGE RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL. Treasurer, John Henry Bicknell, Stuckey's Bank Collector to the Guardians, William Reece, West street ?lIeet at the Board room, Workhouse, West street, on 3rd Relieving & Vaccination Officers, No. 1 district, F. E. Day, friday in each month at II a. m. Eastville, Weston-super-Mare; No. 2 district, Herbert Chairman. W. Petheram W. Berry, Churchill; No. 3 district, Frederick Curtin, Clerk, William Reeca, West street Wedmore; No. 4 district, R. S. Waddon, Brent Knoll Treasurer, John Henry Bicknell, Bank ho. Stuckey's Bank Medical Officers & Public Vaccinators, No. 1 district, A. B. :MedicaI Officer of Health, .A.rtbur VictDr Lecbe L.R.C.P.