Clinical Approach to Recurrent Implantation Failure: Evidence-Based Evaluation of the Endometrium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RNA-Binding Protein Hnrnpll Regulates Mrna Splicing and Stability During B-Cell to Plasma-Cell Differentiation

RNA-binding protein hnRNPLL regulates mRNA splicing and stability during B-cell to plasma-cell differentiation Xing Changa,b, Bin Lic, and Anjana Raoa,b,d,e,1 Divisions of aSignaling and Gene Expression and cVaccine Discovery, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA 92037; bSanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine, La Jolla, CA 92037; and dDepartment of Pharmacology and eMoores Cancer Center, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 Contributed by Anjana Rao, December 2, 2014 (sent for review July 20, 2014) Posttranscriptional regulation is a major mechanism to rewire the RBP-binding sites, thus validating the specificity of RBP binding transcriptomes during differentiation. Heterogeneous nuclear to coprecipitating RNAs and mapping RBP-binding sites on the RNA-binding protein LL (hnRNPLL) is specifically induced in terminally validated RNAs at close to single-nucleotide resolution (8). differentiated lymphocytes, including effector T cells and plasma Heterogeneous nuclear RNA-binding proteins (hnRNPs) is cells. To study the molecular functions of hnRNPLL at a genome- the term applied to a collection of unrelated nuclear RBPs. wide level, we identified hnRNPLL RNA targets and binding sites in hnRNPLL was identified through a targeted lentiviral shRNA plasma cells through integrated Photoactivatable-Ribonucleoside- screen for regulators of CD45RA to CD45RO switching during Enhanced Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) and memory T-cell development (9) and independently through RNA sequencing. hnRNPLL preferentially recognizes CA dinucleo- two separate screens performed by different groups for exclusion tide-containing sequences in introns and 3′ untranslated regions of CD45 exon 4 in a minigene context (10) and for altered CD44 (UTRs), promotes exon inclusion or exclusion in a context-dependent and CD45R expression on T cells in N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea manner, and stabilizes mRNA when associated with 3′ UTRs. -

The E–Id Protein Axis Modulates the Activities of the PI3K–AKT–Mtorc1

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 6, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The E–Id protein axis modulates the activities of the PI3K–AKT–mTORC1– Hif1a and c-myc/p19Arf pathways to suppress innate variant TFH cell development, thymocyte expansion, and lymphomagenesis Masaki Miyazaki,1,8 Kazuko Miyazaki,1,8 Shuwen Chen,1 Vivek Chandra,1 Keisuke Wagatsuma,2 Yasutoshi Agata,2 Hans-Reimer Rodewald,3 Rintaro Saito,4 Aaron N. Chang,5 Nissi Varki,6 Hiroshi Kawamoto,7 and Cornelis Murre1 1Department of Molecular Biology, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, USA; 2Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shiga University of Medical School, Shiga 520-2192, Japan; 3Division of Cellular Immunology, German Cancer Research Center, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany; 4Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, USA; 5Center for Computational Biology, Institute for Genomic Medicine, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, USA; 6Department of Pathology, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, USA; 7Department of Immunology, Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan It is now well established that the E and Id protein axis regulates multiple steps in lymphocyte development. However, it remains unknown how E and Id proteins mechanistically enforce and maintain the naı¨ve T-cell fate. Here we show that Id2 and Id3 suppressed the development and expansion of innate variant follicular helper T (TFH) cells. Innate variant TFH cells required major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-like signaling and were associated with germinal center B cells. -

Detection of Enhancer-Associated Rearrangements Reveals Mechanisms of Oncogene Dysregulation in B-Cell Lymphoma

Published OnlineFirst July 30, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0370 ReseaRch aRticle Detection of Enhancer-Associated Rearrangements Reveals Mechanisms of Oncogene Dysregulation in B-cell Lymphoma Russell J.H. Ryan1,2, Yotam Drier1,2, Holly Whitton2, M. Joel Cotton1,2, Jasleen Kaur1,2, Robbyn Issner2, Shawn Gillespie1,2, Charles B. Epstein2, Valentina Nardi1, Aliyah R. Sohani1, Ephraim P. Hochberg3, and Bradley E. Bernstein1,2 abstRact B-cell lymphomas frequently contain genomic rearrangements that lead to onco- gene activation by heterologous distal regulatory elements. We used a novel approach called “pinpointing enhancer-associated rearrangements by chromatin immunoprecipitation,” or PEAR- ChIP, to simultaneously map enhancer activity and proximal rearrangements in lymphoma cell lines and patient biopsies. This method detects rearrangements involving known cancer genes, including CCND1, BCL2, MYC, PDCD1LG2, NOTCH1, CIITA, and SGK1, as well as novel enhancer duplication events of likely oncogenic significance. We identify lymphoma subtype–specific enhancers in the MYC locus that are silenced in lymphomas with MYC-activating rearrangements and are associated with germline polymorphisms that alter lymphoma risk. We show that BCL6-locus enhancers are acetylated by the BCL6-activating transcription factor MEF2B, and can undergo genomic duplication, or target the MYC promoter for activation in the context of a “pseudo-double-hit” t(3;8)(q27;q24) rearrangement linking the BCL6 and MYC loci. Our work provides novel insights regarding enhancer-driven oncogene activa- tion in lymphoma. SIGNIFICANCE: We demonstrate a novel approach for simultaneous detection of genomic rearrange- ments and enhancer activity in tumor biopsies. We identify novel mechanisms of enhancer-driven regu- lation of the oncogenes MYC and BCL6, and show that the BCL6 locus can serve as an enhancer donor in an “enhancer hijacking” translocation. -

A Dissertation Entitled the Androgen Receptor

A Dissertation entitled The Androgen Receptor as a Transcriptional Co-activator: Implications in the Growth and Progression of Prostate Cancer By Mesfin Gonit Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree in Biomedical science Dr. Manohar Ratnam, Committee Chair Dr. Lirim Shemshedini, Committee Member Dr. Robert Trumbly, Committee Member Dr. Edwin Sanchez, Committee Member Dr. Beata Lecka -Czernik, Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2011 Copyright 2011, Mesfin Gonit This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of The Androgen Receptor as a Transcriptional Co-activator: Implications in the Growth and Progression of Prostate Cancer By Mesfin Gonit As partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree in Biomedical science The University of Toledo August 2011 Prostate cancer depends on the androgen receptor (AR) for growth and survival even in the absence of androgen. In the classical models of gene activation by AR, ligand activated AR signals through binding to the androgen response elements (AREs) in the target gene promoter/enhancer. In the present study the role of AREs in the androgen- independent transcriptional signaling was investigated using LP50 cells, derived from parental LNCaP cells through extended passage in vitro. LP50 cells reflected the signature gene overexpression profile of advanced clinical prostate tumors. The growth of LP50 cells was profoundly dependent on nuclear localized AR but was independent of androgen. Nevertheless, in these cells AR was unable to bind to AREs in the absence of androgen. -

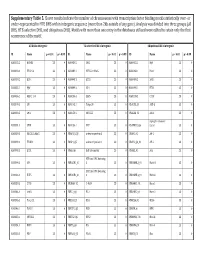

Supplementary Table 5. Clover Results Indicate the Number Of

Supplementary Table 5. Clover results indicate the number of chromosomes with transcription factor binding motifs statistically over‐ or under‐represented in HTE DHS within intergenic sequence (more than 2kb outside of any gene). Analysis was divided into three groups (all DHS, HTE‐selective DHS, and ubiquitous DHS). Motifs with more than one entry in the databases utilized were edited to retain only the first occurrence of the motif. All DHS x Intergenic TEselective DHS x Intergenic Ubiquitous DHS x Intergenic ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 MA0002.2 RUNX1 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0055.1 Myf 23 0 MA0003.1 TFAP2A 23 0 MA0089.1 NFE2L1::MafG 23 0 MA0068.1 Pax4 23 0 MA0039.2 Klf4 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0055.1 Myf 23 0 MA0099.2 AP1 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 MA0056.1 MZF1_1‐4 23 0 MA0136.1 ELF5 23 0 MA0139.1 CTCF 23 0 MA0079.2 SP1 23 0 MA0145.1 Tcfcp2l1 23 0 V$ALX3_01 ALX‐3 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0150.1 NFE2L2 23 0 V$ALX4_02 Alx‐4 23 0 myocyte enhancer MA0081.1 SPIB 23 0 MA0156.1 FEV 23 0 V$AMEF2_Q6 factor 23 0 MA0089.1 NFE2L1::MafG 23 0 V$AP1FJ_Q2 activator protein 1 23 0 V$AP1_01 AP‐1 23 0 MA0090.1 TEAD1 23 0 V$AP4_Q5 activator protein 4 23 0 V$AP2_Q6_01 AP‐2 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 V$AR_Q6 half‐site matrix 23 0 V$ARX_01 Arx 23 0 BTB and CNC homolog MA0099.2 AP1 23 0 V$BACH1_01 1 23 0 V$BARHL1_01 Barhl‐1 23 0 BTB and CNC homolog MA0136.1 ELF5 23 0 V$BACH2_01 2 23 0 V$BARHL2_01 Barhl2 23 0 MA0139.1 CTCF 23 0 V$CMAF_02 C‐MAF 23 0 V$BARX1_01 Barx1 23 0 MA0144.1 Stat3 23 0 -

Coexpression and Relative Abundance Defined by B Cell

Stages of Germinal Center Transit Are Defined by B Cell Transcription Factor Coexpression and Relative Abundance This information is current as Giorgio Cattoretti, Rita Shaknovich, Paula M. Smith, of September 27, 2021. Hans-Martin Jäck, Vundavalli V. Murty and Bachir Alobeid J Immunol 2006; 177:6930-6939; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6930 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/177/10/6930 Downloaded from References This article cites 63 articles, 28 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/177/10/6930.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on September 27, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2006 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Stages of Germinal Center Transit Are Defined by B Cell Transcription Factor Coexpression and Relative Abundance Giorgio Cattoretti,1*† Rita Shaknovich,‡ Paula M. Smith,† Hans-Martin Ja¨ck,§ Vundavalli V. Murty,*† and Bachir Alobeid* The transit of T cell-activated B cells through the germinal center (GC) is controlled by sequential activation and repression of key transcription factors, executing the pre- and post-GC B cell program. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. 492 genes are unique to 0 h post-heat timepoint. The name, p-value, fold change, location and family of each gene are indicated. Genes were filtered for an absolute value log2 ration 1.5 and a significance value of p ≤ 0.05. Symbol p-value Log Gene Name Location Family Ratio ABCA13 1.87E-02 3.292 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family unknown transporter A (ABC1), member 13 ABCB1 1.93E-02 −1.819 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter B (MDR/TAP), member 1 Membrane ABCC3 2.83E-02 2.016 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter C (CFTR/MRP), member 3 Membrane ABHD6 7.79E-03 −2.717 abhydrolase domain containing 6 Cytoplasm enzyme ACAT1 4.10E-02 3.009 acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 Cytoplasm enzyme ACBD4 2.66E-03 1.722 acyl-CoA binding domain unknown other containing 4 ACSL5 1.86E-02 −2.876 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain Cytoplasm enzyme family member 5 ADAM23 3.33E-02 −3.008 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 23 Membrane ADAM29 5.58E-03 3.463 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 29 Membrane ADAMTS17 2.67E-04 3.051 ADAM metallopeptidase with Extracellular other thrombospondin type 1 motif, 17 Space ADCYAP1R1 1.20E-02 1.848 adenylate cyclase activating Plasma G-protein polypeptide 1 (pituitary) receptor Membrane coupled type I receptor ADH6 (includes 4.02E-02 −1.845 alcohol dehydrogenase 6 (class Cytoplasm enzyme EG:130) V) AHSA2 1.54E-04 −1.6 AHA1, activator of heat shock unknown other 90kDa protein ATPase homolog 2 (yeast) AK5 3.32E-02 1.658 adenylate kinase 5 Cytoplasm kinase AK7 -

Targeting Cbx3/Hp1γ Induces LEF-1 and IL-21R to Promote Tumor-In�Ltrating CD8 T-Cell Persistence

Targeting Cbx3/HP1γ Induces LEF-1 and IL-21R to Promote Tumor-Inltrating CD8 T-Cell Persistence To-Ha Thai ( [email protected] ) Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Phuong Le Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Ngoc Ha Drexel University Ngan Tran Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Andrew Newman Institut für Zell- und Neurobiologie Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin Katharine Esselen Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School John Dalrymple Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Harvard Medical School Eva Schmelz Virginia Tech Avinash Bhandoola National Cancer Institute https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4657-8372 Hai-Hui Xue Hackensack University Medical Center https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9163-7669 Prim Singh Nazarbayev University School of Medicine Article Keywords: Cbx3/HP1g, LEF-1, IL-21R or IL-21 receptor, tumor-inltrating CD8+ T-cell persistence, adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT), effector memory/progenitor memory CD8+ T cells, ovarian cancer, neuroblastoma, melanoma. Posted Date: March 29th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-343458/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Targeting Cbx3/HP1g Induces LEF-1 and IL-21R to Promote Tumor-Infiltrating CD8 T- Cell Persistence Phuong T. Le1, Ngoc Ha1,3, Ngan K. Tran1,4, Andrew G. Newman5, Katharine M. Esselen6, John L. Dalrymple6, Eva M. Schmelz7, Avinash Bhandoola8,11, Hai-Hui Xue9,11, Prim B. Singh10,11, and To-Ha -

Discrete Roles of STAT4 and STAT6 Transcription Factors in Tuning Epigenetic Modifications and Transcription During T Helper Cell Differentiation

Immunity Resource Discrete Roles of STAT4 and STAT6 Transcription Factors in Tuning Epigenetic Modifications and Transcription during T Helper Cell Differentiation Lai Wei,1,5 Golnaz Vahedi,1,5 Hong-Wei Sun,2 Wendy T. Watford,1 Hiroaki Takatori,1 Haydee L. Ramos,1 Hayato Takahashi,1 Jonathan Liang,1 Gustavo Gutierrez-Cruz,3 Chongzhi Zang,4 Weiqun Peng,4 John J. O’Shea,1 and Yuka Kanno1,* 1Molecular Immunology and Inflammation Branch 2Biodata Mining and Discovery Section 3Laboratory of Muscle Stem Cells and Gene Regulation NIAMS, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD 20892, USA 4Department of Physics, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA 5These authors contributed equally to this work *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.003 SUMMARY constrain immune-mediated damage (Sakaguchi et al., 2008). Thus, the attainment of these cell fates is critical not only for Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 proper elimination of pathogens, but also for avoidance of (STAT4) and STAT6 are key factors in the specifica- damage to the host (Reiner, 2007). tion of helper T cells; however, their direct roles in The microenvironment of the naive CD4+ T cell greatly influ- driving differentiation are not well understood. Using ences its specification, with a key factor being the cytokine chromatin immunoprecipitation and massive parallel milieu. A major means by which cytokines exert their effect is sequencing, we quantitated the full complement of through activation of signal transducer and activator of transcrip- tion (STAT) family transcription factors, which translocate to the STAT-bound genes, concurrently assessing global nucleus, bind to the regulatory region of genes and induce tran- STAT-dependent epigenetic modifications and scription (Levy and Darnell, 2002; Schindler and Darnell, 1995). -

1 1 EBNA3 Proteins Regulate EBNA2 Binding to Distinct RBPJ Genomic

JVI Accepted Manuscript Posted Online 30 December 2015 J. Virol. doi:10.1128/JVI.02737-15 Copyright © 2015, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. 1 2 EBNA3 proteins regulate EBNA2 binding to distinct RBPJ genomic sites 3 4 Anqi Wang1, Rene Welch2, Bo Zhao3, Tram Ta2, Sündüz Keleș2,4 and Eric Johannsen1, * 5 6 7 1 Department of Medicine and Oncology, McArdle Laboratory For Cancer Research, University of 8 Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53715, USA 9 2 Department of Statistics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53715, USA 10 3 The Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard 11 Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 12 4 Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53715, 13 USA 14 * Corresponding author mailing address: Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin, 1111 15 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705. Phone: (608) 262-9952. E-mail: 16 [email protected] 17 18 19 Running Title: Genome-wide analysis of EBNA3 DNA binding 20 Keywords: EBNA3, EBNA2, Notch signaling, RBPJ, IRF4, transformation, 21 Word Count Abstract: 250 1 22 ABSTRACT 23 Latent infection of B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in vitro results in their immortalization 24 into lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs); this latency program is controlled by the EBNA2 viral 25 transcriptional activator that targets promoters via RBPJ, a DNA binding protein in the Notch signaling 26 pathway. Three other EBNA3 proteins (EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C) interact with RBPJ to 27 regulate cell gene expression. The mechanism by which EBNAs regulate different genes via RBPJ 28 remains unclear. -

BCL6 Overexpression Prevents Increase in Reactive Oxygen Species and Inhibits Apoptosis Induced by Chemotherapeutic Reagents in B-Cell Lymphoma Cells

Oncogene (2003) 22, 4459–4468 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL PAPERS BCL6 overexpression prevents increase in reactive oxygen species and inhibits apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic reagents in B-cell lymphoma cells Tetsuya Kurosu1, Tetsuya Fukuda1, Tohru Miki1 and Osamu Miura*,1 1Department of Hematology and Oncology, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyoku, Tokyo 113-8519, Japan Chromosomal translocations and somatic mutations diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (Kerckaert occurring in the 50 noncoding region of the BCL6 gene, et al., 1993; Ye et al., 1993; Miki et al., 1994). The BCL6 encoding a transcriptional repressor, are most frequent gene encodes a transcriptional repressor containing a genetic abnormalities associated with non-Hodgkin B-cell carboxy-terminal DNA-binding zinc-finger domain and lymphoma and result in deregulated expression of BCL6. an amino-terminal BTB/POZ domain, which can bind However, the significance of deregulated expression of to transcriptional repressor cofactors, including N-CoR BCL6 in lymphomagenesis and its effect on clinical and SMRT, and, thereby, recruit the histone deacetylase outcomes of lymphoma patients have remained elusive. In protein complex (reviewed in Dent et al., 2002; Niu, the present study, we established Daudi and Raji B-cell 2002). BCL6is preferentially expressed in germinal lymphoma cell lines that overexpress BCL6 or its mutant, center B cells and has been demonstrated to be required BCL6-Ala333/343, in which serine residues required for for the formation of germinal centers (Cattoretti et al., degradation through the proteasome pathway in B-cell 1995; Onizuka et al., 1995; Dent et al., 1997; Fukuda receptor-stimulated cells are mutated. -

Nutritional Status Modifies Pregnane X Receptor Regulated Transcriptome

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Nutritional status modifes pregnane X receptor regulated transcriptome Fatemeh Hassani-Nezhad-Gashti1,2, Outi Kummu1,2, Mikko Karpale1,2, Jaana Rysä 3 & Jukka Hakkola 1,2* Pregnane X receptor (PXR) regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, but little is known of the nutritional regulation of PXR function. We investigated the genome wide efects of the nutritional status on the PXR mediated gene regulation in the liver. Mice were treated with a PXR ligand pregnenolone 16α-carbonitrile (PCN) for 4 days and subsequently either fasted for 5 hours or after 4-hour fast treated with intragastric glucose 1 hour before sample collection. Gene expression microarray study indicated that PCN both induced and repressed much higher number of genes in the glucose fed mice and the induction of multiple well-established PXR target genes was potentiated by glucose. A subset of genes, including bile acid synthesis gene Cyp8b1, responded in an opposite direction during fasting and after glucose feeding. PXR knockout abolished these efects. In agreement with the Cyp8b1 regulation, PCN also modifed the bile acid composition in the glucose fed mice. Contribution of glucose, insulin and glucagon on the observed nutritional efects was investigated in primary hepatocytes. However, only mild impact on PXR function was observed. These results show that nutritional status modifes the PXR regulated transcriptome both qualitatively and quantitatively and reveal a complex crosstalk between PXR and energy homeostasis. Pregnane X receptor (PXR) is a master xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. PXR has a broad ligand preference and it accepts numerous clinically used drugs and environmental contaminants as ligands1.