Practical Issues for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Vicky Pham, MS, Evita Henderson-Jackson, MD, Matthew P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: a Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S

Med. J. 258 CASE REPORT: MYOSAIRCOMAMYOSARCOMA OFUTERINEOF UTERINE TUBE Canad.Feb. 3, 1968, Ass.vol. 98 dans 1'cesophage superieur. Le plus petit malade REFERENCES chez qui une biopsie fut prelevee pesait 13 livres 1. CROSBY, W. H.: Amer. or. Dig. Dis., 8: 2, 1963. 2. CAREY, J. B., JR.: Gastroenterology, 46: 550, 1964. et 6tait age de 9 mois. 3. BECK, L T. et al.: Bull. Gastroint. EBndosc., 11: 15, 1965. We wish to thank 0. H. Kimbell, Ph.D., H. Robidoux- 4. MCDONALD, W. G.: Gastroenterology, 51: 390, 1966. 5. PARTIN, J. C. AND SCHUBERT, W. K: New Eng. J. Poirier, R.N., R.-M. Leblanc, R.N., D. Michaud, R.N., Med., 274: 94, 1966. and Marc Gigu6re, R.B.P., for their co-operation and 6. KUITUNEN, P. AND VISAKORPI, J. K.: Lancet, 1: 1276, active assistance. 1965. Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: A Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S. ULLMANN, M.D. and MAERIT B. KALLET, M.D., Detroit, Mich., U.S.A. SINCE primary malignant neoplasms of the uterine tube are so rare that no one indi- vidual or clinic has been able to study a large series of patients, the importance of reporting every case has often been emphasized.2-4 Although over 800 cases of primary carcinoma of the tube have been described in the liter- ature,4 up to 1956 only 30 authentic cases of primary sarcoma had been reported and to this number Abrams added another one.1' 8 Recently we had the opportunity to study a patient with primary sarcoma of the fallopian tube. -

A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1

Case Report pISSN 1738-2637 / eISSN 2288-2928 J Korean Soc Radiol 2015;72(4):295-299 http://dx.doi.org/10.3348/jksr.2015.72.4.295 Bilateral Presentation of Pleural Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors: A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1 You Sun Won, MD1, Jai Soung Park, MD1, Sun Hye Jeong, MD1, Sang Hyun Paik, MD1, Heon Lee, MD1, Jang Gyu Cha, MD1, Eun Suk Koh, MD2 Departments of 1Radiology, 2Pathology, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a highly aggressive malignant small cell neoplasm occurring mainly in the abdominal cavity, but it is extremely rare in Received October 13, 2014; Accepted December 21, the pleura. In this case, a 15-year-old male presented with a 1-month history of left 2014 chest pain. Chest radiographs revealed pleural thickening in the left hemithorax and Corresponding author: Jai Soung Park, MD Department of Radiology, Soonchunhyang University chest computed tomography showed multifocal pleural thickening with enhance- College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, 170 Jomaru-ro, ment in both hemithoraces. A needle biopsy of the left pleural lesion was performed Wonmi-gu, Bucheon 420-767, Korea. and the final diagnosis was DSRCT of the pleura. We report this unusual case aris- Tel. 82-32-621-5851 Fax. 82-32-621-5874 E-mail: [email protected] ing from the pleura bilaterally. The pleural involvement of this tumor supports the hypothesis that it typically occurs in mesothelial-lined surfaces. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) Index terms which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distri- Pleura bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the Thickened Pleura original work is properly cited. -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

Uterine Carcinosarcoma Associated with Pelvic Radiotherapy for Sacral Chordoma: a Case Report

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 51 (2012) 89e92 www.tjog-online.com Case Report Uterine carcinosarcoma associated with pelvic radiotherapy for sacral chordoma: A case report Korhan Kahraman a,*, Fırat Ortac a, Duygu Kankaya b, Gulsah Aynaoglu a a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey b Department of Pathology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Accepted 28 December 2010 Abstract Objective: Postirradiation sarcoma of the female genital tract is rare, but a recognized event. Most reported cases have been associated with history of radiotherapy for various gynecologic conditions, particularly cancer of the uterine cervix and abnormal uterine bleeding. The occurrence of uterine sarcoma secondary to radiotherapy for a non-gynecologic tumor and, furthermore, this condition being simultaneous with the recurrence of primary tumor is unique. Case Report: A 67-year-old woman presented with a uterine mass which was diagnosed as a sarcoma by endometrial curettage and history of pelvic radiotherapy 23 years previously for sacral chordoma. Surgical staging procedure for uterine malignancy was performed. The final pathologic diagnosis was carcinosarcoma of the uterus. Conclusion: In uterine masses seen in patients with history of irradiation to the pelvic field, the probability of uterine sarcomas should always be kept in mind. These tumors may occur simultaneously with recurrence of primary tumor previously treated by adjuvant radiation therapy. Copyright Ó 2012, Taiwan Association of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Published by Elsevier Taiwan LLC. -

Well-Differentiated Spindle Cell Liposarcoma

Modern Pathology (2010) 23, 729–736 & 2010 USCAP, Inc. All rights reserved 0893-3952/10 $32.00 729 Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma (‘atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor’) does not belong to the spectrum of atypical lipomatous tumor but has a close relationship to spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of six cases Thomas Mentzel1, Gabriele Palmedo1 and Cornelius Kuhnen2 1Dermatopathologie, Friedrichshafen, Germany and 2Institute of Pathology, Medical Center, Mu¨nster, Germany Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma represents a rare atypical/low-grade malignant lipogenic neoplasm that has been regarded as a variant of atypical lipomatous tumor. However, well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma tends to occur in subcutaneous tissue of the extremities, the trunk, and the head and neck region, contains slightly atypical spindled tumor cells often staining positively for CD34, and lacks an amplification of MDM2 and/or CDK4 in most of the cases analyzed. We studied a series of well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcomas arising in two female and four male patients (age of the patients ranged from 59 to 85 years). The neoplasms arose on the shoulder, the chest wall, the thigh, the lower leg, the back of the hand, and in paratesticular location. The size of the neoplasms ranged from 1.5 to 10 cm (mean: 6.0 cm). All neoplasms were completely excised. The neoplasms were confined to the subcutis in three cases, and in three cases, an infiltration of skeletal muscle was seen. Histologically, the variably cellular neoplasms were composed of atypical lipogenic cells showing variations in size and shape, and spindled tumor cells with slightly enlarged, often hyperchromatic nuclei. -

Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry for Canine Cutaneous Round Cell Tumours — Retrospective Analysis of 60 Cases

FOLIA HISTOCHEMICA ORIGINAL PAPER ET CYTOBIOLOGICA Vol. 57, No. 3, 2019 pp. 146–154 Diagnostic immunohistochemistry for canine cutaneous round cell tumours — retrospective analysis of 60 cases Katarzyna Pazdzior-Czapula, Mateusz Mikiewicz, Michal Gesek, Cezary Zwolinski, Iwona Otrocka-Domagala Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Olsztyn, Poland Abstract Introduction. Canine cutaneous round cell tumours (CCRCTs) include various benign and malignant neoplastic processes. Due to their similar morphology, the diagnosis of CCRCTs based on histopathological examination alone can be challenging, often necessitating ancillary immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. This study presents a retrospective analysis of CCRCTs. Materials and methods. This study includes 60 cases of CCRCTs, including 55 solitary and 5 multiple tumours, evaluated immunohistochemically using a basic antibody panel (MHCII, CD18, Iba1, CD3, CD79a, CD20 and mast cell tryptase) and, when appropriate, extended antibody panel (vimentin, desmin, a-SMA, S-100, melan-A and pan-keratin). Additionally, histochemical stainings (May-Grünwald-Giemsa and methyl green pyronine) were performed. Results. IHC analysis using a basic antibody panel revealed 27 cases of histiocytoma, one case of histiocytic sarcoma, 18 cases of cutaneous lymphoma of either T-cell (CD3+) or B-cell (CD79a+) origin, 5 cases of plas- macytoma, and 4 cases of mast cell tumours. The extended antibody panel revealed 2 cases of alveolar rhabdo- myosarcoma, 2 cases of amelanotic melanoma, and one case of glomus tumour. Conclusions. Both canine cutaneous histiocytoma and cutaneous lymphoma should be considered at the beginning of differential diagnosis for CCRCTs. While most poorly differentiated CCRCTs can be diagnosed immunohis- tochemically using 1–4 basic antibodies, some require a broad antibody panel, including mesenchymal, epithelial, myogenic, and melanocytic markers. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

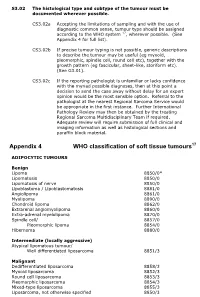

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Misdiagnosed Infantile Rhabdomyofibrosarcoma: a Case Report

2766 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 12: 2766-2768, 2016 Misdiagnosed infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma: A case report TAO PAN1*, KEN CHEN1*, RUN-SONG JIANG2 and ZHENG‑YAN ZHAO2 Departments of 1General Surgery and 2Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, P.R. China Received January 19, 2015; Accepted February 16, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2016.5032 Abstract. Infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma is a rare form of infantile fibrosarcoma has uniform, solidly‑packed spindle cells soft‑tissue tumor often associated with difficulties in diagnosis. arranged in a fascicular or herringbone pattern similar to the The disease is positioned intermediately between rhabdo- vascular pattern observed with hemangiopericytoma (4). Infan- myosarcoma and infantile fibrosarcoma in terms of clinical tile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma may be identified as childhood presentation, immunohistochemistry, behavior, morphology spindle‑cell sarcoma with a low degree of rhabdoid differentiation and ultrastructural features. Reports of rhabdomyofibrosarcoma and aggressive clinical behavior (5). Overlooking the diagnosis cases are limited in the literature. The present case describes a of infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma may increase the chances 26‑month‑old female who presented with a slowly progressive, of local recurrence or metastatic disease; therefore, aggressive soft‑tissue mass in the right chest wall. The mass was success- multimodality treatment is required for these patients (6). Reports fully treated with surgery. Using histopathology, the tumor was of rhabdomyofibrosarcoma cases are limited in the literature. diagnosed and classified as infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma. The present case report describes a 26‑month‑old patient who The patient has been followed‑up for 2 years and is currently presented with a slowly progressive, soft‑tissue mass in the right in good condition. -

Pleural Mesothelioma Dilated and the Pulmonary Trunk Was Occluded by a Large Embolus

Thorax 1993;48:409-410 409 lungs showed fibrosis, subpleural honeycomb Liposarcomatous changes, chronic bronchitis, and foci of bron- chopneumonia. The heart was slightly differentiation in diffuse enlarged (weight 430 g, right ventricle 120 g, left ventricle 230 g). The right side was Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.48.4.409 on 1 April 1993. Downloaded from pleural mesothelioma dilated and the pulmonary trunk was occluded by a large embolus. The left atrium J Krishna, M T Haqqani was occupied by a large myxoid tumour mass measuring 15 x 6 cm attached to a blood clot which extended into the pulmonary veins. The rest of the organs showed no abnor- Abstract malities. A case history is presented of a woman who died eight hours after hospital MICROSCOPICAL APPEARANCES admission with severe breathlessness. At The right pleura was diffusely infiltrated by necropsy the right lung was encased in a the tumour, which showed a sarcomatous thickened pleura with a large tumour. pattern with myxoid change and abundant Histological examination of the tumour typical lipoblasts containing sharply defined showed pleural mesothelioma with cytoplasmic vacuoles indenting hyperchro- liposarcomatous differentiation. The matic nuclei in the right upper lobe. This was lungs showed changes of asbestosis and confirmed on the electron microscope after the asbestos fibre count was significandy the tissue was post fixed in osmium tetraoxide raised. Liposarcomatous differentiation (fig 1). The right upper lobe also showed an in pleural mesothelioma has not been adjacent mesothelioma with an epithelial reported previously. glandular component (fig 2), uniformly nega- tive for carcinoembryonic antigen but (Thorax 1993;48:409-410) strongly positive for epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin. -

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Classifications

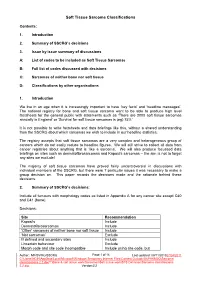

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Classifications Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Summary of SSCRG’s decisions 3. Issue by issue summary of discussions A: List of codes to be included as Soft Tissue Sarcomas B: Full list of codes discussed with decisions C: Sarcomas of neither bone nor soft tissue D: Classifications by other organisations 1. Introduction We live in an age when it is increasingly important to have ‘key facts’ and ‘headline messages’. The national registry for bone and soft tissue sarcoma want to be able to produce high level factsheets for the general public with statements such as ‘There are 2000 soft tissue sarcomas annually in England’ or ‘Survival for soft tissue sarcomas is (eg) 75%’ It is not possible to write factsheets and data briefings like this, without a shared understanding from the SSCRG about which sarcomas we wish to include in our headline statistics. The registry accepts that soft tissue sarcomas are a very complex and heterogeneous group of cancers which do not easily reduce to headline figures. We will still strive to collect all data from cancer registries about anything that is ‘like a sarcoma’. We will also produce focussed data briefings on sites such as dermatofibrosarcomas and Kaposi’s sarcomas – the aim is not to forget any sites we exclude! The majority of soft tissue sarcomas have proved fairly uncontroversial in discussions with individual members of the SSCRG, but there were 7 particular issues it was necessary to make a group decision on. This paper records the decisions made and the rationale behind these decisions. 2. Summary of SSCRG’s decisions: Include all tumours with morphology codes as listed in Appendix A for any cancer site except C40 and C41 (bone). -

The Best Diagnosis Is

Dermatopathology Diagnosis Superficial Plantar Fibromatosis The best diagnosis is: H&E, original magnification 40. a. dermatofibroma b. keloid CUTISc. neurofibroma d. nodular fasciitis Do Note. superficialCopy plantar fibromatosis H&E, original magnification 400. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 225 FOR DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION Luke Lennox, BA; Anna Li, BS; Thomas N. Helm, MD Mr. Lennox and Dr. Helm are from the Department of Dermatology, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Ms. Li is from the Department of Dermatology, Ross University, Dominica, West Indies. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Thomas N. Helm, MD, Dermatopathology Laboratory, 6255 Sheridan Dr, Building B, Ste 208, Williamsville, NY 14221 ([email protected]). 220 CUTIS® WWW.CUTIS.COM Copyright Cutis 2013. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Dermatopathology Diagnosis Discussion Superficial Plantar Fibromatosis lantar fibromatosis typically presents as firm represents a reactive proliferation of spindle cells most plaques or nodules on the plantar surface of the often encountered on the extremities of young adults. Pfoot.1 The process is caused by a proliferation of Spindle cells are loosely arranged in a mucinous fibroblasts and collagen and has been associated with stroma and are not circumscribed (tissue culture ap- trauma, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, and pearance). Vesicular nuclei are encountered, but there alcoholism.2 Unlike the fibromatoses associated with is no remarkable nuclear pleomorphism. Extravasated Gardner syndrome, superficial plantar fibromatosis has not been associated with abnormalities in the ade- nomatous polyposis coli gene or with the -catenin gene.3,4 Lesions typically present in middle-aged or elderly individuals and involve the medial plantar fas- cia.