Lipoblastoma: a Rare Soft Palate Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

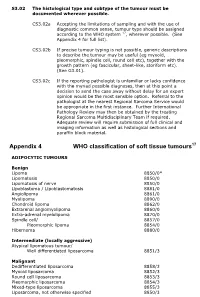

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

The Role of Cytogenetics and Molecular Diagnostics in the Diagnosis of Soft-Tissue Tumors Julia a Bridge

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, S80–S97 S80 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 The role of cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors Julia A Bridge Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare, comprising o1% of all cancer diagnoses. Yet the diversity of histological subtypes is impressive with 4100 benign and malignant soft-tissue tumor entities defined. Not infrequently, these neoplasms exhibit overlapping clinicopathologic features posing significant challenges in rendering a definitive diagnosis and optimal therapy. Advances in cytogenetic and molecular science have led to the discovery of genetic events in soft- tissue tumors that have not only enriched our understanding of the underlying biology of these neoplasms but have also proven to be powerful diagnostic adjuncts and/or indicators of molecular targeted therapy. In particular, many soft-tissue tumors are characterized by recurrent chromosomal rearrangements that produce specific gene fusions. For pathologists, identification of these fusions as well as other characteristic mutational alterations aids in precise subclassification. This review will address known recurrent or tumor-specific genetic events in soft-tissue tumors and discuss the molecular approaches commonly used in clinical practice to identify them. Emphasis is placed on the role of molecular pathology in the management of soft-tissue tumors. Familiarity with these genetic events -

The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: News and Perspectives

PATHOLOGICA 2021;113:70-84; DOI: 10.32074/1591-951X-213 Review The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives Marta Sbaraglia1, Elena Bellan1, Angelo P. Dei Tos1,2 1 Department of Pathology, Azienda Ospedale Università Padova, Padova, Italy; 2 Department of Medicine, University of Padua School of Medicine, Padua, Italy Summary Mesenchymal tumours represent one of the most challenging field of diagnostic pathol- ogy and refinement of classification schemes plays a key role in improving the quality of pathologic diagnosis and, as a consequence, of therapeutic options. The recent publica- tion of the new WHO classification of Soft Tissue Tumours and Bone represents a major step toward improved standardization of diagnosis. Importantly, the 2020 WHO classi- fication has been opened to expert clinicians that have further contributed to underline the key value of pathologic diagnosis as a rationale for proper treatment. Several rel- evant advances have been introduced. In the attempt to improve the prediction of clinical behaviour of solitary fibrous tumour, a risk assessment scheme has been implemented. NTRK-rearranged soft tissue tumours are now listed as an “emerging entity” also in con- sideration of the recent therapeutic developments in terms of NTRK inhibition. This deci- sion has been source of a passionate debate regarding the definition of “tumour entity” as well as the consequences of a “pathology agnostic” approach to precision oncology. In consideration of their distinct clinicopathologic features, undifferentiated round cell sarcomas are now kept separate from Ewing sarcoma and subclassified, according to the underlying gene rearrangements, into three main subgroups (CIC, BCLR and not Received: October 14, 2020 ETS fused sarcomas) Importantly, In order to avoid potential confusion, tumour entities Accepted: October 19, 2020 such as gastrointestinal stroma tumours are addressed homogenously across the dif- Published online: November 3, 2020 ferent WHO fascicles. -

Oncology–Solid Tumor

Solid Tumor An overview for school professionals Solid Tumor is an abnormal mass that does not contain cysts or liquid areas. There are several types of solid tumors. They include: Ewing’s Sarcoma, Germ Cell Tumor/Germinoma, Hepatoblastoma, Lipoblastoma, Malignant Fibrous Histiosarcoma, Neuroblastoma, Osteosarcoma, Retinoblastoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, Synovial Sarcoma, and Wilms Tumor. Common treatment for a solid tumor diagnosis consists of chemotherapy, radiation, and possible surgery. What are some common symptoms of a solid tumor? Pain in specific body part Weight Loss Fatigue Nausea/Vomiting Decreased alertness Decreased ability to attend to tasks What type of support plan is appropriate for a student with a solid tumor? Students with a solid tumor should have a 504 plan/IEP. The diagnosis of a solid tumor gives reasonable cause to bypass the SST process, which will allow you to provide immediate accommodations to the student. All teachers who provide instruction for your student should be made aware of these accommodations. What accommodations are necessary for a student with a solid tumor? ATTENDANCE: Students with a solid tumor frequently miss school. They may require hospitalizations from time to time, sometimes for several weeks. full-time and/or intermittent hospital homebound services suspension of attendance requirements for absences due to medical appointments and illness, including allowances for student to participate in extra-curricular programs and events without penalty due to absences. partial-day attendance, as necessary ASSIGNMENTS: It is important for teacher and parents to ensure that student receive assignments in a timely manner so student does not get further behind. It may also take the student with a solid tumor longer to complete assignments due to fatigue, pain, and/or frequent trips to the restroom. -

Integrated Data Analysis Reveals Uterine Leiomyoma Subtypes with Distinct Driver Pathways and Biomarkers

Integrated data analysis reveals uterine leiomyoma subtypes with distinct driver pathways and biomarkers Miika Mehinea,b, Eevi Kaasinena,b, Hanna-Riikka Heinonena,b, Netta Mäkinena,b, Kati Kämpjärvia,b, Nanna Sarvilinnab,c, Mervi Aavikkoa,b, Anna Vähärautiob, Annukka Pasanend, Ralf Bützowd, Oskari Heikinheimoc, Jari Sjöbergc, Esa Pitkänena,b, Pia Vahteristoa,b, and Lauri A. Aaltonena,b,e,1 aMedicum, Department of Medical and Clinical Genetics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FIN-00014, Finland; bResearch Programs Unit, Genome-Scale Biology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FIN-00014, Finland; cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Helsinki University Hospital, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FIN-00029, Finland; dDepartment of Pathology and HUSLAB, Helsinki University Hospital, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FIN-00014, Finland; and eDepartment of Biosciences and Nutrition, Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 77, Stockholm, Sweden Edited by Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, and approved December 18, 2015 (received for review September 25, 2015) Uterine leiomyomas are common benign smooth muscle tumors that with deletions affecting collagen, type IV, alpha 5 and collagen, type impose a major burden on women’s health. Recent sequencing studies IV, alpha 6 (COL4A5-COL4A6) may constitute a rare fourth subtype have revealed recurrent and mutually exclusive mutations in leiomyo- (4). HMGA2 and MED12 represent the two most common driver mas, suggesting the involvement of molecularly distinct pathways. In genes and together contribute to 80–90% of all leiomyomas (5). this study, we explored transcriptional differences among leiomyomas Less frequently, leiomyomas harbor 6p21 rearrangements af- harboring different genetic drivers, including high mobility group fecting high mobility group AT-hook 1 (HMGA1) (6). -

Case Report Perineal Lipoblastoma: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7(6):3370-3374 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0000325 Case Report Perineal lipoblastoma: a case report and review of literature Qiang Liu1*, Zheng Xu1*, Shunbao Mao1, Rongyao Zeng1, Wenyou Chen1, Qiang Lu1, Yihe Guo2, Jing Liu1* 1Department of General Surgery, 175 Hospital of PLA (Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University), 269 Zhanghua Middle Road, Zhangzhou 363000, Fujian Province, China; 2Department of Pathology, 175 Hospital of PLA, 269 Zhanghua Middle Road, Zhangzhou 363000, Fujian Province, China. *Equal contributors. Received March 25, 2014; Accepted May 23, 2014; Epub May 15, 2014; Published June 1, 2014 Abstract: Lipoblastoma is a rare benign mesenchymal tumor that composes of embryonal white fat tissue and typi- cally occurs in infants or young children under 3 years of age. It usually affects the extremities, trunk, head, and neck. The perineum is a rare location with only 7 cases reported in the literature. We describe a case of 3-year-old girl with a lipoblastoma arising from perineum. An approximately 4.5 cm × 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm nodule was resected in left perineum with satisfied results. Pathological examination showed that it was composed of small lobules of mature and immature fat cells, separated by fibrous septa containing small dilated blood vessels. The left perineal lipoblastoma, although rare, should be differentiated from some other mesenchymal tumors with similar histologic and cytological features. Keywords: Perineum, lipoblastoma, myxoid liposarcoma, childhood, pathology Introduction Case report Lipoblastoma was first described by Jaffe in A 3-year-old girl was admitted to the Department 1926 [1]. -

Practical Issues for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Vicky Pham, MS, Evita Henderson-Jackson, MD, Matthew P

Pathology Report Practical Issues for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Vicky Pham, MS, Evita Henderson-Jackson, MD, Matthew P. Doepker, MD, Jamie T. Caracciolo, MD, Ricardo J. Gonzalez, MD, Mihaela Druta, MD, Yi Ding, MD, and Marilyn M. Bui, MD, PhD Background: Retroperitoneal sarcoma is rare. Using initial specimens on biopsy, a definitive diagnosis of histological subtypes is ideal but not always achievable. Methods: A retrospective institutional review was performed for all cases of adult retroperitoneal sarcoma from 1996 to 2015. A review of the literature was also performed related to the distribution of retroperitoneal sarcoma subtypes. A meta-analysis was performed. Results: Liposarcoma is the most common subtype (45%), followed by leiomyosarcoma (21%), not otherwise specified (8%), and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (6%) by literature review. Data from Moffitt Cancer Center demonstrate the same general distribution for subtypes of retroperitoneal sarcoma. A pathology-based algorithm for the diagnosis of retroperitoneal sarcoma is illustrated, and common pitfalls in the pathology of retroperitoneal sarcoma are discussed. Conclusions: An informative diagnosis of retroperitoneal sarcoma via specimens on biopsy is achievable and meaningful to guide effective therapy. A practical and multidisciplinary algorithm focused on the histopathology is helpful for the management of retroperitoneal sarcoma. Introduction tic, and predictive information based on a relatively Soft-tissue sarcomas are mesenchymal neoplasms small amount of tissue obtained -

Lipoblastoma of the Tongue: a Rare Case Report Ying Zeng, Chenyi Mao, Li Lin, Hua-Liang Xiao* and Qiaonan Guo

Case Report iMedPub Journals Medical Case Reports 2018 www.imedpub.com Vol.4 No.1:59 ISSN 2471-8041 DOI: 10.21767/2471-8041.100094 Lipoblastoma of the Tongue: A Rare Case Report Ying Zeng, Chenyi Mao, Li Lin, Hua-liang Xiao* and Qiaonan Guo Daping Hospital and Research Institute of Surgery, The Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, P.R. China *Corresponding author: Hua-liang Xiao, Daping Hospital and Research Institute of Surgery, The Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, P.R. China, Tel: +86 431 8565 6921; E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 08, 2018; Accepted: February 20, 2018; Published: February 22, 2018 Citation: Zeng Y, Mao C, Lin L, Xiao H, Guo Q, et al. (2018) Lipoblastoma of the Tongue: A Rare Case Report. Med Case Rep Vol.4 No. 1:59. granulation tissue composed of a large number of newborn capillaries, lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils (Figure Abstract 1A). In another area, adipose lobules with focal myxoid stroma segmented by coarse fiber were observed (Figures 1B and 1C). Lipoblastoma, a rare benign tumor originating from white Mature adipose cells, spindle-shaped cells and stellate cells fetal adipose tissue, occurs primarily in infancy and early with a mucous background, coarse collagen fibers, and childhood. Lipoblastoma commonly occurs in the trunk vacuolated lipoblasts were observed at high magnification and upper and lower extremities and is less common in (Figure 1D), and the lipoblasts were positive for S-100 (Figure the head and neck, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum. 1E) and p16 (Figure 1F). These findings confirmed a diagnosis No case of lipoblastoma of the tongue has been reported of lipoblastoma. -

Pleomorphic Lipoma • Chondroid Lipoma

PATHOLOGY UPDATE: SurgicalDiagnostic Pearls for the Practicing Pathologist Friday, October 7, 2016 Aria® Resort & Casino • Las Vegas, Nevada Educational Symposia TABLE OF CONTENTS Friday, October 7, 2016 The Trouble with Fat: Diagnostic Issues in Well-Differentiated Lipomatous Tumors (John R. Goldblum, M.D.) ................ 1 Practical Approach to Melanocytic Tumor (Steven D. Billings, M.D.) .................................................................. 15 Reporting of Prostate Cancer in Needle Biopsy Specimens: Gleason Grading and More (David J. Grignon, M.D., FRCP(C)) ..................................................................... 45 Unraveling the Mesenchymal Madness in Gynecologic Tumors (Kristen A. Atkins, M.D.) ........................................ 73 REGISTER TODAY - 2017 Pathology Symposia 1 2 The Trouble With Fat: Diagnostic Issues in Well-Differentiated Lipomatous Tumors John R. Goldblum, M.D. Chairman, Department of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic Professor of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine Cleveland, Ohio Benign Lipomatous Tumors Lipomatous Tumors of Intermediate Malignancy • Lipoma • Angiomyolipoma • Lipoblastoma • Myelolipoma Atypical lipomatous tumor • Angiolipoma • Hibernoma (Well-differentiated liposarcoma) • Myolipoma • Spindle cell / pleomorphic lipoma • Chondroid lipoma Liposarcoma Malignant Lipomatous Tumors • Atypical lipomatous tumor (well-differentiated liposarcoma) • Dedifferentiated liposarcoma • lipoma-like • Myxoid liposarcoma • sclerosing • Round cell liposarcoma • inflammatory -

Oral Cavity Lipoma

ORIGINAL ARTICLE J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2019; 55(2): 148-159. Oral cavity lipoma: a study of 101 cases in a Brazilian population Lipoma de cavidade oral: um estudo de 101 casos em uma população brasileira 10.5935/1676-2444.20190017 Rafael L. V. Osterne1; Renata M. B. Lima-Verde2; Eveline Turatti1; Cassiano Francisco W. Nonaka3; Roberta B. Cavalcante1 1. Universidade de Fortaleza (Unifor), Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. 2. Centro Universitário Christus (Unichristus), Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. 3. Universidade Estadual da Paraíba (UEPB), Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil. ABSTRACT Introduction: Lipomas are benign soft tissue tumors commonly found in the human body. Although common in the head and neck region, in the oral cavity region they are uncommon, accounting for only 1% to 4% of benign oral cavity lesions. Objective: This study aims to identify the clinical and histopathological characteristics of oral cavity lipomas subjected to histopathological analysis at a pathology laboratory in the city of Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. Methods: Data from all cases of oral lesions diagnosed as lipoma and confirmed by histopathological examination over a period of 10 years were collected, including: gender, age, anatomical location, clinical diagnosis and histopathological subtypes. Results: During the period evaluated, 101 cases were diagnosed as lipomas, representing 1.01% of oral cavity biopsies. Females were more affected, with a male/female ratio of 1: 1.8, and with a peak of incidence between 50 and 70 years of age. The buccal mucosa was the most affected anatomical region, followed by the lower lip. Classic lipoma and fibrolipoma were the histological variants of lipoma most commonly found in the oral cavity, with 64 cases of classic lipoma and 29 cases of fibrolipoma. -

Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology (1127-1316)

VOLUME 31 | SUPPLEMENT 2 | MARCH 2018 MODERN PATHOLOGY 2018 ABSTRACTS GYNECOLOGIC AND OBSTETRIC PATHOLOGY (1127-1316) 107TH ANNUAL MEETING GEARED TO LEARN Vancouver Convention Centre MARCH 17-23, 2018 Vancouver, BC, Canada PLATFORM & 2018 ABSTRACTS POSTER PRESENTATIONS EDUCATION COMMITTEE Jason L. Hornick, Chair Amy Chadburn Rhonda Yantiss, Chair, Abstract Review Board Ashley M. Cimino-Mathews and Assignment Committee James R. Cook Laura W. Lamps, Chair, CME Subcommittee Carol F. Farver Steven D. Billings, Chair, Interactive Microscopy Meera R. Hameed Shree G. Sharma, Chair, Informatics Subcommittee Michelle S. Hirsch Raja R. Seethala, Short Course Coordinator Anna Marie Mulligan Ilan Weinreb, Chair, Subcommittee for Rish Pai Unique Live Course Offerings Vinita Parkash David B. Kaminsky, Executive Vice President Anil Parwani (Ex-Officio) Deepa Patil Aleodor (Doru) Andea Lakshmi Priya Kunju Zubair Baloch John D. Reith Olca Basturk Raja R. Seethala Gregory R. Bean, Pathologist-in-Training Kwun Wah Wen, Pathologist-in-Training Daniel J. Brat ABSTRACT REVIEW BOARD Narasimhan Agaram Mamta Gupta David Meredith Souzan Sanati Christina Arnold Omar Habeeb Dylan Miller Sandro Santagata Dan Berney Marc Halushka Roberto Miranda Anjali Saqi Ritu Bhalla Krisztina Hanley Elizabeth Morgan Frank Schneider Parul Bhargava Douglas Hartman Juan-Miguel Mosquera Michael Seidman Justin Bishop Yael Heher Atis Muehlenbachs Shree Sharma Jennifer Black Walter Henricks Raouf Nakhleh Jeanne Shen Thomas Brenn John Higgins Ericka Olgaard Steven Shen Fadi Brimo Jason -

Two Synchronous Neonatal Tumors: an Extremely Rare Case

Hindawi Case Reports in Pathology Volume 2021, Article ID 6674372, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6674372 Case Report Two Synchronous Neonatal Tumors: An Extremely Rare Case M. Rodríguez-Zubieta,1 K. Albarenque,1 C. Lagues,1 A. San Roman,1 M. Varela,2 D. Russo,3 G. Podesta,4 D. Steinberg,5 C. Schauvinhold,5 A. Etchegaray,6 and M. T. G. de Dávila 1 1Department of Pathology, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina 2Department of Oncology, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina 3Department of Pediatric Surgery, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina 4Department of Liver Surgery and Transplantation, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina 5Department of Plastic Surgery, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina 6Fetal Medicine Unit, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina Correspondence should be addressed to M. T. G. de Dávila; [email protected] Received 7 January 2021; Revised 19 March 2021; Accepted 3 April 2021; Published 19 April 2021 Academic Editor: Atif A. Ahmed Copyright © 2021 M. Rodríguez-Zubieta et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We report a case of a newborn with two synchronous tumors—sialoblastoma and hepatoblastoma—diagnosed at 20 weeks of gestation by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography (US). The aim of this study was to describe the management of this case together with a review of the literature. Our patient had a large facial tumor associated with extremely high alpha-fetoprotein levels.