The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: News and Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who, How and What of Pathology of Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Editorial Page 1 of 11 Who, how and what of pathology of soft tissue sarcoma Salvatore Lorenzo Renne Anatomic Pathology Unit, Humanitas Research Hospital, Humanitas University, Rozzano, MI 20089, Italy Correspondence to: Salvatore Lorenzo Renne. Adjunct Teaching Professor, Anatomic Pathology Unit, Humanitas Research Hospital, Humanitas University, Via Manzoni 56, Rozzano, MI 20089, Italy. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Aug 06, 2018. Accepted for publication Aug 23, 2018. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.10.09 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cco.2018.10.09 Introduction to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) adipocytes (lipoma, spindle cells lipoma, hibernoma, well- pathology differentiated liposarcoma (LPS), myxoid LPS, etc.). One chapter is dedicated to specific entities “of uncertain STS is a generic term that refers to a heterogeneous group differentiation” that are well-characterized entities that do of rare neoplastic diseases. The aim of this review is to not readily resemble any normal mesenchymal cells (as the discuss the role of pathology in the multidisciplinary Ewing sarcoma or the synovial sarcoma—a clear misnomer). management of STS patients. This will be done: (I) The last chapter is dedicated to those sarcomas that do illustrating the framework for the current classification; (II) not follow in any of the previously listed diagnosis and are examining the characteristics that allows an expert diagnosis; therefore called “undifferentiated/unclassified sarcomas” (III) describing the role of the sarcoma pathologist -

Rare Skin Cancers in General Practice

CLINICAL PRACTICE Skin cancer Rare skin cancers in series general practice Case study Anthony Dixon Mr LA has long been troubled with actinic damage to his skin, especially his face. He has had MBBS, FACRRM, is many squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) removed and many solar keratoses managed. dermasurgeon and Director On this occasion Mr LA had two actinic lesions on his left cheek that failed to respond to of Research, Skin Alert cryotherapy (Figure 1). A biopsy of each site produced a surprise. Histology of the superior Skin Cancer Clinics and lesion revealed sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 2). This is an uncommon yet aggressive cutaneous Skincanceronly, Belmont, malignancy derived from sebaceous glands. The 5 year survival rate is 60–70%. Victoria. anthony@ The tumour was widely excised with a minimum 10 mm margin. A multidisciplinary approach skincanceronly.com resulted in a decision not to proceed to adjunctive radiotherapy. The wound was well healed by 8 weeks (Figure 3). Four years on there is no sign of local or regional recurrence (Figure 4). Many sebaceous carcinomas occur on the eyelids where the outcome is often poor;1 and some patients are prone to multiple other cutaneous SCCs. There is also a rare syndrome called Muir-torre of visceral neoplasms associated with sebaceous carcinoma on the skin.2 As this is an autosomal dominant condition, family history and counselling is an esssential part of management (enquire about family history of internal malignancies). A family member's diagnosis can be Figure 3. Satisfactory healing 8 weeks Figure 1. Two actinic lesions on the left face following wide excision of sebaceous important for other family members and offers screening have failed to respond to cryotherapy carcinoma for internal and cutaneous malignancies. -

Complete Case of a Rare but Benign Soft Tissue Tumor

Hindawi Case Reports in Orthopedics Volume 2019, Article ID 6840693, 5 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6840693 Case Report Hibernoma of the Upper Extremity: Complete Case of a Rare but Benign Soft Tissue Tumor Thomas Reichel ,1 Kilian Rueckl,1 Annabel Fenwick,1,2 Niklas Vogt,3 Maximilian Rudert,1 and Piet Plumhoff1 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Koenig-Ludwig-Haus, University of Wuerzburg, Brettreichstraße 11, 97074 Wuerzburg, Germany 2Department of Trauma Surgery, Klinikum Augsburg, 86156 Augsburg, Germany 3Department of Pathology, University of Wuerzburg, 97080 Wuerzburg, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to Thomas Reichel; [email protected] Received 26 February 2019; Accepted 14 April 2019; Published 21 May 2019 Academic Editor: Elke R. Ahlmann Copyright © 2019 Thomas Reichel et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Hibernoma is a rare benign lipomatous tumor showing differentiation of brown fatty tissue. To the author’s best knowledge, there is no known case of malignant transformation or metastasis. Due to their slow, noninfiltrating growth hibernomas are often an incidental finding in the third or fourth decade of life. The vast majority are located in the thigh, neck, and periscapular region. A diagnostic workup includes ultrasound and contrast-enhanced MRI. Differential diagnosis is benign lipoma, well- differentiated liposarcoma, and rhabdomyoma. An incisional biopsy followed by marginal resection of the tumor is the standard of care, and recurrence after complete resection is not reported. The current paper presents diagnostic and intraoperative findings of a hibernoma of the upper arm and reviews similar reports in the current literature. -

Atypical Compound Nevus Arising in Mature Cystic Ovarian Teratoma

J Cutan Pathol 2005: 32: 71–123 Copyright # Blackwell Munksgaard 2005 Blackwell Munksgaard. Printed in Denmark Journal of Cutaneous Pathology Abstracts of the Papers Presented at the 41st Annual Meeting of The American Society of Dermatopathology Westin Copley Place Boston, Massachusetts, USA October 14–17, 2004 These abstracts were presented in oral or poster format at the 41st Annual Meeting of The American Society of Dermatopathology on October 14–17, 2004. They are listed on the following pages in alphabetical order by the first author’s last name. 71 Abstracts IN SITU HYBRIDIZATION IS A VALUABLE DIAGNOSTIC A 37-year-old woman with diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) TOOL IN CUTANEOUS DEEP FUNGAL INFECTIONS presented with asymptomatic non-palpable purpura of the lower J.J. Abbott1, K.L. Hamacher2,A.G.Bridges2 and I. Ahmed1,2 extremities. Biopsy of a purpuric macule revealed a perivascular Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology1 and and focally nodular lymphocytic infiltrate with large numbers of Dermatology2, plasma cells, seemingly around eccrine glands. There was no vascu- litis. The histologic findings in the skin were strikingly similar to those Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN, USA of salivary, parotid, and other ‘‘secretory’’ glands affected in SS. The cutaneous manifestations of SS highlighted in textbooks include Dimorphic fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidiomy- xerosis, annular erythema, small-vessel vasculitis, and pigmented cosis, and cryptococcosis) can occur in immunocompromised and purpura. This case illustrates that purpura in skin of patients with healthy individuals. Cutaneous involvement is often secondary and SS may be caused by a peri-eccrine plasma-rich infiltrate. -

Angiomyolipoma of the Cervix – Report of a Rare Entity

Internet Journal of Medical Update. 2017 July;12(2):13-15. doi: 10.4314/ijmu.v12i2.4 Internet Journal of Medical Update Journal home page: http://www.akspublication.com/ijmu Case Report Angiomyolipoma of the cervix – report of a rare entity N. Hariharanadha Sarmaᴪ1, Rama Srivastava2, Smriti Agnihotri3 1Consultant Pathologist, Department of Pathology, RDT Hospital, Bathalapalli, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Professor, Department of Pathology, SSR Medical College, Belle Rive, Mauritius 3Professor, Department of Pathology, American University of Antigua College of Medicine, Antigua & Barbuda, WI (Received 22 September 2017 and accepted 04 October 2017) ABSTRACT: Angiomyolipoma (AML) is a mesenchymal neoplasm seen usually in the kidney. Few cases of extra renal AML have been documented in various organs including the female genital tract, where the uterus is the most common site. To the best of our knowledge, only 4 cases of AML in the cervix have been reported in the literature. Association of AML with tuberous sclerosis is well known. Presently AML is included in the spectrum of disease entities called PEComa. We report a case of AML without tuberous sclerosis arising from the uterine cervix, which has to be differentiated from lipoleiomyoma. KEY WORDS: Angiomyolipoma; Uterine cervix; PEComas; Uterine tumor INTRODUCTIONV localization8, and mostly in females over 409. The occurrence of AML in the cervix without Angiomyolipoma (AML) occurs most frequently in concurrent incidence in the kidney is extremely the kidney, where it is closely related to tuberous rare, and only four cases have been reported in the sclerosis complex (TSC)1,2, occasionally in other scientific literature10. We are reporting a case of organs, most commonly the liver, but occurrence at uterine cervix AML without tuberous sclerosis other sites is extremely rare3. -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

The Use of High Tumescent Power Assisted Liposuction in the Treatment of Madelung’S Collar

Letter to the Editor The use of high tumescent power assisted liposuction in the treatment of Madelung’s collar Henryk Witmanowski1,2, Łukasz Banasiak1, Grzegorz Kierzynka1, Jarosław Markowicz1, Jerzy Kolasiński1, Katarzyna Błochowiak3, Paweł Szychta1,4 1Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Medical College in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland 2Department of Physiology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 3Department of the Oral Surgery, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 4Department of Oncological Surgery and Breast Diseases, Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital-Research Institute, Lodz, Poland Adv Dermatol Allergol 2017; XXXIV (4): 366–371 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2017.69319 Mild symmetrical lipomatosis (plural symmetrical The disease most commonly takes a proximal form lipomatosis, multiple symmetric lipomatosis – MSL), which takes the following areas of the body with the fol- also known as Madelung’s disease or Launois-Bensaude lowing frequency: the genial area 92.3%, cervical region syndrome is a rare disease of unknown etiology, first de- 67.7%, shoulder region 54.8%, abdominal 45.2%, chest scribed by Brodie in 1846, Madelung in 1888, and Launois 41.9%, thigh and pelvic rim 32.3% [11, 12]. The periph- with Bensaude in 1898 [1–3]. eral type mainly locates on both sides at the level of the Madelung’s disease incidence is 1 : 250000 [4]. Mul- hands, feet and knees, this is definitely a rarer form of tiple symmetric lipomatosis occurs mainly in the inhabit- the disease. The mixed form is described very rarely. The ants of the Mediterranean area and Eastern Europe, in specified central type is also engaged primarily around males (male to female ratio is 20 : 1), aged 30–70 years, the lower torso, and intermediate parts of the legs. -

Well-Differentiated Spindle Cell Liposarcoma

Modern Pathology (2010) 23, 729–736 & 2010 USCAP, Inc. All rights reserved 0893-3952/10 $32.00 729 Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma (‘atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor’) does not belong to the spectrum of atypical lipomatous tumor but has a close relationship to spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of six cases Thomas Mentzel1, Gabriele Palmedo1 and Cornelius Kuhnen2 1Dermatopathologie, Friedrichshafen, Germany and 2Institute of Pathology, Medical Center, Mu¨nster, Germany Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma represents a rare atypical/low-grade malignant lipogenic neoplasm that has been regarded as a variant of atypical lipomatous tumor. However, well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma tends to occur in subcutaneous tissue of the extremities, the trunk, and the head and neck region, contains slightly atypical spindled tumor cells often staining positively for CD34, and lacks an amplification of MDM2 and/or CDK4 in most of the cases analyzed. We studied a series of well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcomas arising in two female and four male patients (age of the patients ranged from 59 to 85 years). The neoplasms arose on the shoulder, the chest wall, the thigh, the lower leg, the back of the hand, and in paratesticular location. The size of the neoplasms ranged from 1.5 to 10 cm (mean: 6.0 cm). All neoplasms were completely excised. The neoplasms were confined to the subcutis in three cases, and in three cases, an infiltration of skeletal muscle was seen. Histologically, the variably cellular neoplasms were composed of atypical lipogenic cells showing variations in size and shape, and spindled tumor cells with slightly enlarged, often hyperchromatic nuclei. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

Non-Wilms Renal Cell Tumors in Children

PEDIATRIC UROLOGIC ONCOLOGY 0094-0143/00 $15.00 + .OO NON-WILMS’ RENAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN Bruce Broecker, MD Renal tumors other than Wilms’ tumor are tastases occur in 40% to 60% of patients with infrequent in childhood. Wilms’ tumors ac- clear cell sarcoma of the kidney, whereas they count for 6% to 7% of childhood cancer, are found in less than 2% of patients with whereas the remaining renal tumors account Wilms’ tumor.**,26 This distinct clinical behav- for less than l%.27The most common non- ior is one of the features that has led to its Wilms‘ tumors are clear cell sarcoma of the designation as a separate tumor. Other clini- kidney, rhabdoid tumor of the kidney (both cal features include a lack of association with formerly considered unfavorable Wilms’ tu- sporadic aniridia or hemihypertrophy. mor variants but now considered separate tu- Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney has not mors), renal cell carcinoma, mesoblastic been reported to occur bilaterally and is not nephroma, and multilocular cystic nephroma. associated with nephroblastomatosis. It has Collectively, these tumors account for less been reported in infancy and adulthood, but than 10% of the primary renal neoplasms in the peak incidence is between 3 and 5 years childhood. of age. It has an aggressive behavior that responds poorly to treatment with vincristine and actinomycin alone, leading to its original CLEAR CELL SARCOMA designation by Beckwith as an unfavorable histology pattern. The addition of doxorubi- Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney is cur- cin in aggressive chemotherapy regimens has rently considered a separate tumor distinct improved outcome. -

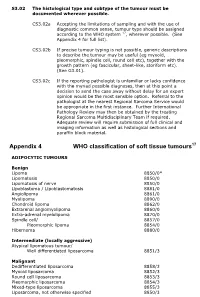

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Atypical Fibroxanthoma - Histological Diagnosis, Immunohistochemical Markers and Concepts of Therapy

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 35: 5717-5736 (2015) Review Atypical Fibroxanthoma - Histological Diagnosis, Immunohistochemical Markers and Concepts of Therapy MICHAEL KOCH1, ANNE J. FREUNDL2, ABBAS AGAIMY3, FRANKLIN KIESEWETTER2, JULIAN KÜNZEL4, IWONA CICHA1* and CHRISTOPH ALEXIOU1* 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, University Hospital Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany; 2Dermatology Clinic, 3Institute of Pathology, and 4ENT Department, University Hospital Mainz, Mainz, Germany Abstract. Background: Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is an in 1962 (2). The name 'atypical fibroxanthoma' reflects the uncommon, rapidly growing cutaneous neoplasm of uncertain tumor composition, containing mainly xanthomatous-looking histogenesis. Thus far, there are no guidelines for diagnosis and cells and a varying proportion of fibrocytoid cells with therapy of this tumor. Patients and Methods: We included 18 variable, but usually marked cellular atypia (3). patients with 21 AFX, and 2,912 patients with a total of 2,939 According to previous reports, AFX chiefly occurs in the AFX cited in the literature between 1962 and 2014. Results: In sun-exposed head-and-neck area, especially in elderly males our cohort, excision with safety margin was performed in 100% (3). There are two disease peaks described: one within the 5th of primary tumors. Local recurrences were observed in 25% of to 7th decade of life and another one between the 7th and 8th primary tumors and parotid metastases in 5%. Ten-year disease- decade. The former disease peak is associated with lower specific survival was 100%. The literature research yielded 280 tumor frequency (21.8%) and tumors that do not necessarily relevant publications. Over 90% of the reported cases were manifest on skin areas exposed to sunlight (4).