Avignon Vs. Rome: Dante, Petrarch, Catherine of Siena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

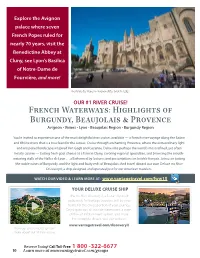

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Bishop Robert Barron Recommended Books

BISHOP ROBERT BARRON’S Recommended Books 5 FAVORITE BOOKS of ALL TIME SUMMA THEOLOGIAE Thomas Aquinas THE DIVINE COMEDY Dante Alighieri THE SEVEN STOREY MOUNTAIN Thomas Merton MOBY DICK Herman Melville MACBETH William Shakespeare FAVORITE Systematic Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Summa Theologiae St. Thomas • On the Trinity (De trinitate) St. Augustine • On First Principles (De principiis) Origen • Against the Heresies (Adversus haereses) Irenaeus • On the Development of Christian Doctrine John Henry Newman MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • The Spirit of Catholicism Karl Adam • Catholicism Henri de Lubac • Glory of the Lord, Theodrama, Theologic Hans Urs von Balthasar • Hearers of the Word Karl Rahner • Insight Bernard Lonergan • Introduction to Christianity Joseph Ratzinger • God Matters Herbert McCabe FAVORITE Moral Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Secunda pars of the Summa theologiae Thomas Aquinas • City of God St. Augustine • Rule of St. Benedict • Philokalia Maximus the Confessor et alia MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • The Sources of Christian Ethics Servais Pinckaers • Ethics Dietrich von Hilldebrand • The Four Cardinal Virtues and Faith, Hope, and Love Josef Pieper • The Cost of Discipleship Dietrich Bonhoeffer • Sanctify Them in the Truth: Holiness Exemplified Stanley Hauerwas FAVORITE Biblical Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Sermons Origen • Sermons and Commentary on Genesis and Ennarationes on the Psalms Augustine • Commentary on John, Catena Aurea, Commentary on Job, Commentary on Romans Thomas Aquinas • Commentary on the Song of Songs Bernard of Clairvaux • Parochial and Plain Sermons John Henry Newman MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • Jesus and the Victory of God and The Resurrection of the Son of God N.T. Wright • The Joy of Being Wrong James Alison • The Theology of the Old Testament Walter Brueggemann • The Theology of Paul the Apostle James D.G. -

6 X 10.Three Lines .P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51530-6 - Rhetoric beyond Words: Delight and Persuasion in the Arts of the Middle Ages Edited by Mary Carruthers Index More information Index Abelard, Peter 133, 160, 174, 250–1, 275 and ductus 215, 216, 228, 239–43 Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad and memory 215–16, 231, 233, 239–43 Romanos 252–4 and scholasticism 20–8 Commentary on Boethius’ De differentiis arrangement (dispositio) in 36–8, 229–30 topicis 202, 251 as concept in rhetorical discourse 4, 26, 27, Easter liturgy for Paraclete 256–63 32, 190–1 Letter 5 257–8 borrows rhetorical vocabulary 4, 7, 36–7 on rhetoric 202, 251–63 compared to poetry 26, 190–1 accent see inflection Aristotle 24–5, 131 Accursius (Bolognese jurist) 125 influence of Physics and Metaphysics Ackerman, James S. 40 21–2, 24–5 acting 161–3, 166–7 on epistēmē, téchnē and empeiría 1–2 compared to oratory 10, 127, 157–8 on ethos, logos and pathos 7 masks and 158–9 Rhetoric 2, 7, 36, 127, 128 actio see delivery theory of causality 21–2, 24–5 Adam of Dryburgh (Adam Scot), De tripartite Topics 202 tabernaculo 233, 242 Arnulf of St Ghislain 65 Aelred of Rievaulx (abbot) 124, 133–5 arrangement (dispositio) De spiritali amicitia 134 and ductus 196, 199–206, 229–30, 263 agency as mapping 191–2 of audiences 2, 165–6 Geoffrey of Vinsauf on 190–2 of ductus 199–206 in architecture 36–8, 229–30 of roads 191 personified as ‘Deduccion’ 205–6 of the work itself 201–2 Quintilian on 4, 230 shared by composer and performer 88 see also consilium; ductus; maps, mapping; Agrippa (Roman emperor) 281–3 -

Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation to A. D. 1825

: TABLES OP CONTEMPORARY CHUONOLOGY. FROM THE CREATION, TO A. D. 1825. \> IN SEVEN PARTS. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." 3lorttatttt PUBLISHED BY SHIRLEY & HYDE. 1629. : : DISTRICT OF MAItfE, TO WIT DISTRICT CLERKS OFFICE. BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the first day of June, A. D. 1829, and in the fifty-third year of the Independence of the United States of America, Messrs. Shiraey tt Hyde, of said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors, in the words following, to wit Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation, to A.D. 1825. In seven parts. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled " An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ;" and also to an act, entitled "An Act supplementary to an act, entitled An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ; and for extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." J. MUSSEV, Clerk of the District of Maine. A true copy as of record, Attest. J MUSSEY. Clerk D. C. of Maine — TO THE PUBLIC. The compiler of these Tables has long considered a work of this sort a desideratum. -

July 2018 New Arrivals

1 New Arrivals July 2018 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 [email protected] * http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store) Saturday: By Appointment Only, Pacific time (in-store only- phone not answered). Catalog listings are formatted as follows: Item No. Author Title Publisher No. of Pages Condition Binding Year Cost ABBREVIATIONS FOR BINDING: dj= hardcover w/dustjacket hc= hardcover w/out dustjacket L= full or half leather pb = paperback Re-= re-bound, usually in buckram V=vinyl or leatherette ABBREVIATIONS FOR CONDITION: If no condition is noted, you may assume the book is in very good to fine condition. Our abbreviations used to describe defects are as follows: As is= condition is poor; details available upon request br= broken binding ch= chipped or torn (usually refers to dust jacket condition) Fx= foxing highlt= highlighting m= musty mks or ul= underlining, highlighting, or marginalia pncl= pencil marks S or st = stained or grubby sh= shaken or weak hinges sl= slight v= very wr or wrn= worn (usually in reference to exterior) wrp= warped X or XL= ex-library Y or yellow = yellowed pages OUR TERMS: We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and PayPal. Available books that you have requested will be reserved for 1 business day after our order confirmation, to allow time for payment arrangements. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. -

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

Aachen, 13 Absolutism, 12 Académie D'architecture, 100 Académie Des Beaux-Arts, 100 Académie Des Belles-Lettres De Caen, 12

The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert's Secret State Intelligence System Jacob Soll http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=243021 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Index Aachen, 13 152; information management, 143–52; Absolutism, 12 and politics, 142 Académie d’Architecture, 100 Archives, 7, 11; archival pillages, 101–8, Académie des Beaux-Arts, 100 126; de Brienne archive, 103; Colbert Académie des Belles-Lettres de Caen, and archives, 37, 104–12; colonial 123–24 archives, 113–19; Dutch archives, 24; Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- ecclesiastical archives, 103–6; Fouquet’s Lettres, 100, 109, 128 archive, “la Cassette de Fouquet,” 46; Académie des Inscriptions et Médaillons, French parliamentary archives, 43–44, 100 108; French state archives, 28–30, Académie des Sciences, 100, 109 101–8; Fugger family archive, 19; ge- Académie Française, 31 nealogical archives, 182–83; medieval Académie Française de Rome, 100 archives, 14–15; nineteenth- Académie Politique of de Torcy, 156 century centralizing state archives, Accounting, 18, 34, 36, 54–58; and Louis 158–59; openness and archives, 166; XIV, 60–66 and Orientalism, 105–7; permanent Agendas, 6, 18; made for Louis XIV, state archives, 158; Renaissance 51–66; of Seignelay, 89 archives, 16; and royal authority, 162; D’Aguesseau, Henri de, intendant, 91 searchable archives, 158; and secrecy, Alberti, Leon Battista, 54, 57 166; Spanish Archives, 19–21 Amelot de La Houssaye, Abraham- Archivio di Stato di Torino, 163 Nicolas, 54, 57 Archivio Segreto del Vaticano, 22, 28 American Historical Association, 11 Arnoul, Nicolas, intendant, 73–74, 106 Amsterdam, 24–25 Arnoul, Pierre, ‹ls, intendant, 78–79 Ancient Constitution, the, 13, 29, 31, Ars apodemica, 70–72 49 Ars mercatoria, 18, 35 Ann of Austria, Queen of France, 38, 58 Atlantic World, lack of concept of, 115, Antiquarianism, 25–33; and government, 118 269 The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert's Secret State Intelligence System Jacob Soll http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=243021 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. -

Sedgwick Opens New Offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe, to Further Expand Its Operations in France and in French Overseas Territory

Sedgwick opens new offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe, to further expand its operations in France and in French overseas territory PARIS, 19 February 2021 – Sedgwick, a leading global provider of technology-enabled risk, benefits and integrated business solutions, today announced the opening of three new offices in Corsica and Gap, southern France and in Guadeloupe, French overseas department and region. This expansion will increase the company’s capacity to assist the evolving needs of existing and future clients in various parts of France and the overseas departments and regions and build on its growing market presence. The new offices will increase Sedgwick’s footprint and meet the growing demand for specialist claims and loss adjusting solutions in France and the overseas departments in the Caribbean. Sedgwick also plans to continue recruiting and expanding local teams in various parts of France in order to capitalize on this significant market opportunity. The combination of a national network, highly performant digital tools and local experts will present clients with better tailored solutions and well adapted to any specific given event. In the coming months, Sedgwick aims to open several more offices as part of its overall strategic plan to expand its footprint, as well as to increase proximity with clients and their policyholders. As such, there are plans to launch several new offices in 2021, in Metropolitan France and Monaco. Xavier Gazay, president and director general of Sedgwick in France said: “The opening of our new offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe is another indicator of the momentum we are building to maximize the country’s growth opportunities. -

The Church and the People of God: Fragments of a Constitution Al History*

THE CHURCH AND THE PEOPLE OF GOD: FRAGMENTS OF A CONSTITUTION AL HISTORY* By J.T. Me PARTLIN I THE re-appraisal of the place of the laity in the Church is well-known to be a task which at once arouses the suspicion and hostility of a certain type of Catholic: it eamed Newman himself a formal delation to Rome for heresy, l and the attitude of Newman' s opponents has unfortunately not disappeated with the passage of time, but remains to complicate still further an already sufficiently complex discussion. For some, to recom mend a new vision of the laity is nothing less than a chal1enge to the authority of the Church, cal1ing in question the collective wisdom of Catho1icism which has ordained the present relationship of the two orders. On the other hand, ie is now becoming painfully evident that a great deal of our present situation is due more to historical accident than to the considered decision of the Church, and that some of the Church's collective wisdom is thereby obscured rather than expressed - for in the recent past the Church has 'appeated above everything else to be a reli gious organisation for practical aims, of an outspoken juridical character. The mystical element in her, everything that stood behind the palpable aims and arrangements, everything that expressed itself in the concept of the Kingdom of God, of the mystical Body of Christ, would not be perceived at once.'2 The restoration of these hitherto obscured elements, moreover, is no merely academic question, for the needs of the modem world are now widely recognised to require a thoroughly activt;! partici pation of the laity in the Church' s life. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89754-9 - An Introduction to Medieval Theology Rik Van Nieuwenhove Index More information Index Abelard, Peter, 82, 84, 99–111, 116, 120 beatific vision, 41, 62, 191 Alain of Lille, 71 beatitude, 172, 195–96 Albert the Great, 171, 264 Beatrijs van Nazareth, 170 Alexander of Hales, 147, 211, 227 beguine movement, 170 allegory, 15, 43, 45, 47, 177 Benedict XII, Pope, 265 Amaury of Bène, 71 Benedict, St., 28–29, 42 Ambrose, 7, 10, 149 Berengar of Tours, 60, 83, 129, 160, see also amor ipse notitia est 51, 117, see love and knowledge Eucharist anagogy, 47 Bernard of Clairvaux, 79, 82, 100, 104, 110, 112–15, analogy, see univocity 147, 251 analogy in Aquinas, 182–85, 234, 235 critique of Abelard, 110–11 Anselm of Canterbury, 16, 30, 71, 78, 81, 83–98, on loving God, 112–14 204, 236 Boccaccio, Giovanni, 251 Anselm of Laon, 72, 99 Boethius, 29–33, 125, 137 Anthony, St., 27 Bonaventure, 34, 47, 123, 141, 146, 148, 170, 173, apophaticism, 8, 34, 271 176, 179, 211–24, 227, 228, 230, 232, 242, 243, Aquinas, 182–83 245, 254 Aquinas, 22, 24, 34, 47, 51, 72, 87, 89, 90, 133, 146, Boniface, Pope, 249 148, 151, 154, 164, 169, 171–210, 214, 225, 227, 230, 235, 236, 237, 238, 240, 241, 244, 246, Calvin, 14 254, 255, 257, 266 Carabine, Deirdre, 65 Arianism, 20, 21 Carthusians, 79 Aristotle, 9, 20, 29, 78, 84, 179, 181, 192, 195, 212, Cassian, John, 27–29, 47 213, 216, 223, 225, 226, 227, 229, 237, 254, Cassidorius, 124 267, 268 cathedral schools, 82, 169 Arts, 124, 222 Catherine of Siena, 251 and pedagogy (Hugh), 124–28 -

Index Nominum

Index Nominum Abualcasim, 50 Alfred of Sareshal, 319n Achillini, Alessandro, 179, 294–95 Algazali, 52n Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio, Ali, Ismail, 8n, 132 205n Alkindi, 304 Adam, 313 Allan, Mowbray, 276n Adam of Papenhoven, 222n Alne, Robert, 208n Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 136n Alonso, Manual, 46 Adenulf of Anagni, 301, 384 Alphonse of Poitiers, 193, 234 Adrian IV, pope, 108 Alverny, Marie-Thérèse d’, 35, 46, Afonso I Henriques, king of Portu- 50, 53n, 93, 147, 177, 264n, 303, gal, 35 308n Aimery, archdeacon of Tripoli, Alvicinus de Cremona, 368 105–6 Amadaeus VIII, duke of Savoy, Alberic of Trois Fontaines, 100–101 231 Albert de Robertis, bishop of Ambrose, 289 Tripoli, 106 Anastasius IV, pope, 108 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Anti- Anatoli, Jacob, 113 och, 73, 77n, 86–87, 105–6, 122, Andreas the Jew, 116 140 Andrew of Cornwall, 201n Albert of Schmidmüln, 215n, 269 Andrew of Sens, 199, 200–202 Albertus Magnus, 1, 174, 185, 191, Antonius de Colell, 268 194, 212n, 227, 229, 231, 245–48, Antweiler, Wolfgang, 70n, 74n, 77n, 250–51, 271, 284, 298, 303, 310, 105n, 106 315–16, 332 Aquinas, Thomas, 114, 256, 258, Albohali, 46, 53, 56 280n, 298, 315, 317 Albrecht I, duke of Austria, 254–55 Aratus, 41 Albumasar, 36, 45, 50, 55, 59, Aristippus, Henry, 91, 329 304 Arnald of Villanova, 1, 156, 229, 235, Alcabitius, 51, 56 267 Alderotti, Taddeo, 186 Arnaud of Verdale, 211n, 268 Alexander III, pope, 65, 150 Ashraf, al-, 139n Alexander IV, pope, 82 Augustine (of Hippo), 331 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 311, Augustine of Trent, 231 336–37 Aulus Gellius,