The Hill of Fire Monica Bose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vision a Monthly Journal Started by HH Swami Ramdas in 1933 DEDICATED to UNIVERSAL LOVE and SERVICE

Rs. 40/- ANNUAL The Vision A monthly journal started by HH Swami Ramdas in 1933 DEDICATED TO UNIVERSAL LOVE AND SERVICE VOL. 84 APRIL 2017 NO. 07 ANANDASHRAM, P.O. ANANDASHRAM - 671 531, INDIA VOL. 84 APRIL 2017 No. 07 FULLNESS OF GOD THE world is not there for me. For me the world is God — Every part of it is Divine, There is none but He and I. I! Where is ‘I’ when all is He? I, you and He are one in Him. ‘Tis all one life, one thought, one form, One is the sound and one is the strain. One is the sun and one is the light. In the silence of all-embracing space Thrills one sole rapture of peace. The air breathes and swings To one immortal tune. Fullness of God — perfection of Truth Alone revealed everywhere In pomp, power and glory. — Swami Ramdas Vol. 84 April 2017 No. 07 CONTENTS From The Editor - 5 Knowledge Makes For Freedom - Swami Ramdas 7 Words Of Beloved Papa Swami Ramdas- 9 Words Of Pujya Mataji Krishnabai - 11 Words Of Pujya Swami Satchidananda- 13 ‘I’ And ‘Mine’ Are False Ideas - Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj14 The Illusion Of Ownership - Eckhart Tolle 16 The Discipline Of Universal Love - Swami Sivananda 19 ‘I’ And ‘Mine’ – Cause Of Unhappiness- Shri Brahmachaitanya Maharaj Gondavalekar 21 Misery Comes From ‘I’ And ‘Mine’ - Swami Vivekananda 23 Epistles Of Swami Ramdas - 25 Dear Children - 28 Swami Padmanabhanandaji’s Visit - 30 Anandashram News - 34 THE VISION A Monthly Magazine Anandashram PO Anandashram 671531, Kanhangad, Kerala, India Phone: (0467) 2203036, 2209477, 2207403 Web: www.anandashram.org Email: [email protected] [email protected] For free edition of “THE VISION” on the web, please visit: www.anandashram.org Apr 2017FROM THE EDITOR 5 FROM THE EDITOR There is a marvelous Sufi story that may inspire us to think deep about who we are and where we belong. -

January-December - 2012

JANUARY-DECEMBER - 2012 January 2012 AVOID CONFUSION This world appearance is a confusion as the blue sky is an optical illusion. It is better not to let the mind dwell on it. Neither freedom from sorrow nor realization of one’s real nature is possible as long as the conviction does not arise in us that the world-appearance is unreal. The objective world is a confusion of the real with the unreal. – Yoga Vasishta THE MIND: It is complex. It is logical and illogical, rational and irrational, good and bad, loving and hating, giving and grabbing, full of hope and help, while also filled with hopelessness and helplessness. Mind is a paradox, unpredictable with its own ways of functioning. It is volatile and restless; yet, it constantly seeks peace, stillness and stability. To be with the mind means to live our lives like a roller- coaster ride. The stability and stillness that we seek, the rest and relaxation that we crave for, the peace and calmness that we desperately need, are not to be found in the arena of mind. That is available only when we link to our Higher Self, which is very much with us. But we have to work for it. – P.V. Vaidyanathan LOOK AT THE BRIGHT SIDE: Not everyone will see the greatness we see in ourselves. Our reactions to situations that don’t fit our illusions cause us to suffer. Much of the negative self-talk is based upon reactions to a reality that does not conform to our illusory expectations. We have much to celebrate about, which we forget. -

My Beloved Papa, Swami Ramdas MY BELOVED PAPA, SWAMI Ness of Its Immortal and All-Blissful Nature

Page 12 My Beloved Papa, Swami Ramdas MY BELOVED PAPA, SWAMI ness of its immortal and all-blissful nature. By his very pres- ence he rid the hearts of people of their base and unbridled pas- RAMDAS sions. The faithful derived the greatest benefit by communion By with him.” SWAMI SATCHIDANANDA (of Anandashram) As Papa had attained realisation by taking to uninterrupted chanting of the divine name Ram, coupled with contemplation of the attributes of God, he always extolled the virtue of nama- japa in sadhana. Based upon his personal experience, Papa as- sured all seekers that nama-japa would lead them to the su- preme heights of realisation of one‟s oneness with the Al- mighty. On the power of the Divine Name he has this to say: “The Divine Name is pregnant with a great power to transform the world. It can create light where there is darkness, love where there is hate, order where there is chaos, and happiness where there is misery. The Name can change the entire atmos- phere of the world from one of bitterness, ill will and fear to that of mutual love, goodwill and trust. For the Name is God Himself. To bring nearer the day of human liberation from the sway of hatred and misery, the way is the recognition of the supremacy of God over all things and keeping the mind in tune with the Universal by the chanting of the Divine Name.” May Beloved Papa, who is everything and beyond everything, Mother Krishnabai and Swami Ramdas continue to bless and lead all to the supreme goal! If anyone wants me to tell them something about Beloved OM SRI RAM JAI RAM JAI JAI RAM Papa, I ask them to visualise what it would be like if, by some divine alchemy, Love and Bliss were to coalesce and stand be- fore them as one luminous entity. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

In This Issue the Essence of Instruction

Om Namo Bhagavathe Sri Ramanaya APRIL 2010 Page 1 SaranagathiVOLUME 4, ISSUE 4 Saranagathi eNewsletter from www.sriramanamaharshi.org In this Issue CONTENTS Dear Sri Bhagavan Devotees, In this Issue 1 The Sri Vidya Havan at Sri Ramanasramam The Essence of Instruction 1 commemorates of worship of the Meru Chakra consecrated by the touch of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Sri Venkatarathnam 2 Maharshi. This year the Havan was performed on How I came to the Maharshi 4 Friday 19th March, 2010. The grand event went off well by Sri Bhagavan and Sri Matrubhuteswara’s Grace. Reports from Sri Ramanasramam 5 The Ashram website carries photos and video of the event. A very moving interview of Smt. Hilda Kapur ‘How I came to the Maharshi’ and finally, Reports from has also been added to the ‘Old Devotees’ Interviews’ Sri Ramanasramam. in the website. Lastly we have introduced a ‘Quote of the Day’ which you may avail of. Yours in Sri Bhagavan, This issue of Saranagathi carries an account of Sri Editorial Team. Venkatarathnam who lived with Sri Bhagavan from 1944 to 1950 and served Him in His final years. This is followed by Sri Swami Ramdas’s recollections in The Essence of Instruction Body, senses, mind, breath, sleep – All insentient and unreal – Cannot be ‘I’, ‘I’ who am the Real. - Upadesa Saram by Sri Bhagavan (Verse 22) Page 2 Saranagathi By Neal Rosner (Published in ‘The Maharshi’ newsletter Sep/Oct & Nov/Dec 2007) Venkatarathnam Sri Venkatarathnam lived with Bhagavan from 1944 to 1950. During the last year he served as one of His personal attendants. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

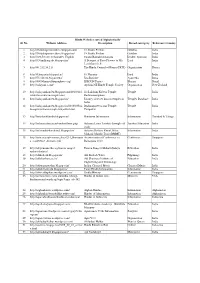

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary Books on the Related Theme by the Same Author

Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary Books on the related theme by the Same Author ● Hinduism: A Gandhian Perspective (2nd Edition) ● Ethics for Our Times: Essays in Gandhian Perspective Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary M.V. NADKARNI Ane Books Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi ♦ Chennai ♦ Mumbai Kolkata ♦ Thiruvananthapuram ♦ Pune ♦ Bengaluru Handbook of Hinduism: Ancient to Contemporary M.V. Nadkarni © Author, 2013 Published by Ane Books Pvt. Ltd. 4821, Parwana Bhawan, 1st Floor, 24 Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002 Tel.: +91(011) 23276843-44, Fax: +91(011) 23276863 e-mail: [email protected], Website: www.anebooks.com Branches Avantika Niwas, 1st Floor, 19 Doraiswamy Road, T. Nagar, Chennai - 600 017, Tel.: +91(044) 28141554, 28141209 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Gold Cornet, 1st Floor, 90 Mody Street, Chana Lane, (Mohd. Shakoor Marg), Opp. Masjid, Fort Mumbai - 400 001, Tel.: +91(022) 22622440, 22622441 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Flat No. 16A, 220 Vivekananda Road, Maniktala, Kolkata - 700 006, Tel.: +91(033) 23547119, 23523639 e-mail: [email protected] # 6, TC 25/2710, Kohinoor Flats, Lukes Lane, Ambujavilasam Road, Thiruvananthapuram - 01, Kerala, Tel.: +91(0471) 4068777, 4068333 e-mail: [email protected] Resident Representative No. 43, 8th ‘‘A’’ Cross, Ittumadhu, Banashankari 3rd Stage Bengaluru - 560 085, Tel.: +91 9739933889 e-mail: [email protected] 687, Narayan Peth, Appa Balwant Chowk Pune - 411 030, Mobile: 08623099279 e-mail: [email protected] Please be informed that the author and the publisher have put in their best efforts in producing this book. Every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the contents. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The Christian Society for the Study of Hinduism, 1940-1956: Interreligious Engagement in Mid-Twentieth Century India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository THE CHRISTIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF HINDUISM, 1940-1956: INTERRELIGIOUS ENGAGEMENT IN MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY INDIA by RICHARD LEROY HIVNER Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject RELIGIOUS STUDIES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR M CLASQUIN JUNE 2011 Acknowledgements This thesis is deeply indebted to many individuals, both historical and contemporary, who have lived in nebulous areas on the borderlands of Hinduism and Christianity. Some of them would object even to this illustration of their engagement with what have come to be understood as two different world religions, and perhaps they are better described as pilgrims in uncharted territory. Nonetheless, my debt and gratitude, particularly to those I am privileged to call friends. Many librarians and archivists have been helpful and generous in my researches over the years. Related to this thesis, particular thanks are due to the librarians and archivists at the United Theological College in Bangalore, the archivists of the CMS collection at the University of Birmingham, and the librarians and archivists at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. The late Fr. James Stuart of the Brotherhood House in Delhi provided access to books and abundant encouragement, and his successors there have continued to provide hospitable access. Thanks are also due to Bishop Raphy Manjaly and Rev. Joseph D’Souza of the diocese of Varanasi of the Roman Catholic Church for making copies of The Pilgrim in their possession available to me. -

Glimpses of Divine Vision Swami Ramdas

Glimpses of Divine Vision Swami Ramdas 1 CONTENTS 1. What is Religion 2. Glory of life 3. Sorrow and Pain 4. God 5. The True Vision 6. Guru and Satsang 7. Faith 8. Peace 9. Love 10. The Lord’s Name 11. Concentration 12. Meditation 13. Self-Surrender 14. General Publishers: The Manager Anandashram, Anandashram PO Kanhangad, India 671531 2 DEDICATION Dedicated with humble pranams to my beloved Sri Sadguru Dev on the occasion of his 61st Birthday – 8th April 1944. T. Bhavani Shanker Rao, A Devotee. 3 Note: The Glimpses were culled from the unpublished letters for the years 1933, 34 &35 of Swami Ramdas and arranged under appropriate headings by the devotee. 4 WHAT IS RELIGION? Try to enter into the mysterious origin of your and the world-life. To know who you are in reality is the real quest. To arrive at this truth you have to, by a systematized process of thought and discipline, transcend all human limitations set by the body, mind and intellect, and then, embarking on the realm of the Spirit, realize your immortal, changeless and blissful nature. This constitutes religion. 34 5 GLORY OF LIFE What is required to set life free and make it blessed is to do all actions in the spirit of perfect surrender to the will of the all-wise Master-the master of your being and of the world- existence. This is possible in all the fields of activity in which you are placed in consonance with your nature and attainments. Life is a game with which you play as you play with a doll. -

Vedic Knowledge for Civilizational Harmony"

World Association for Vedic Studies, Inc. A Multidisciplinary Academic Society, Tax Exempt in USA WAVES 2010 Eighth International Conference on "Vedic Knowledge for Civilizational Harmony" August 4-7, 2010 University of West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago In Collaboration with: Center for Indic Studies, UMass Dartmouth Saraswati Mandiram, Trinidad Contents About WAVES Organizers Welcome Letters WAVES 2010 in Trinidad Conference Description Track Descriptions Abstracts Agenda Speaker Profiles Speaker Guidelines Map of UWI Map of TT Boarding and Lodging Information Key Contacts Sponsors WAVES 2010 2 World Association for Vedic Studies, Inc. A Multidisciplinary Academic Society, Tax Exempt in USA Nature & Purpose World Association of Vedic Studies (WAVES) is a multidisciplinary academic society. It is a forum for all scholarly activities and views on any area of ‘Vedic Studies’ variously called as Indian Studies, South Asian Studies or Indology. WAVES is not confined to study related to Vedas alone or to India alone. It encompasses all that applies to traditions commonly called Vedic, past, present and future, any where in the world. WAVES is a non-religious society with no ideology. It is open for membership and for participation to all persons irrespective of their color, creed, ethnicity, and country of origin or any other kind of persuasion. It is universally acknowledged that Vedas are among the oldest existing records of human thoughts. Vedic traditions have continued without interruption for many millennium of years and remain a living and formative source of Hindu culture and tradition. Today Vedic traditions are not confined to Indian subcontinent but have spread virtually to all parts of the globe, through persons of Indian origin and through scholars and admirers of these traditions.