02-Pasler PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

AUTUNNO in MUSICA Festival De Musique Classique

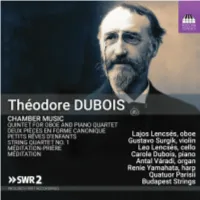

AUTUNNO IN MUSICA Festival de musique classique 16-30 OCTOBRE 2014 Le festival Autunno in Musica fête, en 2014, sa quatrième année d’existence en prolongeant ses ambitions patrimoniales, qui font que le passé revit grâce au présent et qu’il rend le présent plus vivant. Il met, comme toujours, l’accent sur le lieu dans lequel les concerts s’inscrivent, car c’est en partie à la mémoire des compositeurs qui vécurent dans les murs de la Villa Médicis qu’il se consacre, tout en s’ouvrant à une vision renouvelée de la musique écrite entre le XVIIIe siècle et le début du XXe, entre la France et l’Italie. Cette année voisineront certaines « vedettes » du Prix de Rome, comme Claude Debussy et André Caplet, d’autres en pleine réhabilitation comme Théodore Dubois, d’autres enfin dont un vrai travail de redécouverte permet d’apprécier la qualité, comme Gaston Salvayre. Mais Autunno in Musica n’oublie pas non plus certains « refusés » du concours, qu’ils soient « non-récompensés » comme Benjamin Godard et Ernest Chausson, ou seulement second Prix de Rome comme Nadia Boulanger et – ce fut le grand scandale de 1905 – Maurice Ravel. Autunno in Musica fait aussi cette année la part belle aux femmes compositrices, telles Marie Jaëll, Henriette Renié ou encore Cécile Chaminade. Pour défendre cette musique, il fallait que soient rassemblés les meilleurs interprètes actuels, avec un intérêt particulier porté à la jeune génération, capable de lectures audacieuses et inattendues : c’est le cas du jeune harpiste soliste de l’Opéra de Paris, Emmanuel Ceysson, du Trio Arcadis (2e prix du Concours international de musique de chambre de Lyon), de la mezzo-soprano Isabelle Druet (lauréate du Concours Reine Elizabeth et plus récemment du parcours Rising Star), ainsi que du Quatuor Giardini et du pianiste David Bismuth. -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

Mcallister Interview Transcription

Interview with Timothy McAllister: Gershwin, Adams, and the Orchestral Saxophone with Lisa Keeney Extended Interview In September 2016, the University of Michigan’s University Symphony Orchestra (USO) performed a concert program with the works of two major American composers: John Adams and George Gershwin. The USO premiered both the new edition of Concerto in F and the Unabridged Edition of An American in Paris created by the UM Gershwin Initiative. This program also featured Adams’ The Chairman Dances and his Saxophone Concerto with soloist Timothy McAllister, for whom the concerto was written. This interview took place in August 2016 as a promotion for the concert and was published on the Gershwin Initiative’s YouTube channel with the help of Novus New Music, Inc. The following is a full transcription of the extended interview, now available on the Gershwin channel on YouTube. Dr. Timothy McAllister is the professor of saxophone at the University of Michigan. In addition to being the featured soloist of John Adams’ Saxophone Concerto, he has been a frequent guest with ensembles such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Lisa Keeney is a saxophonist and researcher; an alumna of the University of Michigan, she works as an editing assistant for the UM Gershwin Initiative and also independently researches Gershwin’s relationship with the saxophone. ORCHESTRAL SAXOPHONE LK: Let’s begin with a general question: what is the orchestral saxophone, and why is it considered an anomaly or specialty instrument in orchestral music? TM: It’s such a complicated past that we have with the saxophone. -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

The Pianissimo, "The Feast of Eight Hands"

Kennesaw State University College of the Arts School of Music presents Guest Artists The Pianissimo The Musical Arts Association's Piano Ensemble Concert The Feast of Eight Hands Wednesday, February 26, 2014 8:00 p.m Audrey B. and Jack E. Morgan, Sr. Concert Hall Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center Seventy-sixth Concert of the 2013-14 Concert Season Program The Feast of Eight Hands LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) arr. F. X. Chwatal Egmont Overture, Op. 84 for 2 pianos 8 hands KYUNG MEE CHOI (b. 1971) The Mind That Moves for 2 pianos 8 hands (2011)* ALBERT LAVIGNAC (1846-1916) Galop March for 1 piano 8 hands Intermission CHARLES CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921) arr. E.Guiraud Danse Macabre, Op.40 for 2 pianos 8 hands SOONMEE KANG (b. 1948) Poongryu II for 2 pianos 8 hands (2014 revised) MIKHAIL IVANOVICH GLINKA (1804-1857) arr. J. Spindler Overture of Ruslan und Ludmila for 2 pianos 8 hands * It was commissioned and premiered in 2011 by The Pianissimo- The Musical Arts Association. * Pianissimo’s residency at Kennesaw State University is made possible in part by the Global Engagement Grants from the College of the Arts in KSU. * Special thanks to the support by the Asian Studies Program of the Interdisciplinary Studies department in Kennesaw State University. Program Notes Egmont Overture, Op.84 for 2 pianos 8 hands LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN / F. X. CHWATAL Egmont, Op. 84 is a set of incidental music pieces for the play of the same name by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Beethoven wrote it between October 1809 and June 1810, and it was premiered on June 15, 1810. -

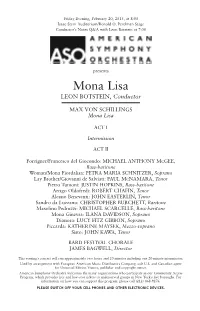

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

TOCC0362DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THÉODORE DUBOIS: CHAMBER MUSIC by William Melton (Clément-François) Théodore Dubois was born in Rosnay (Marne) on 24 August 1837 into an unmusical family. His father was in fact a basket-maker, but saw to it that a second-hand harmonium was purchased so that his son could receive his first music-lessons from the village cooper, M. Dissiry, an amateur organist. The pupil showed indications of strong musical talent and at the age of thirteen he was taken on by the maître de chapelle at Rheims Cathedral, Louis Fanart, a pupil of the noted composers Jean-François Lesueur and Alexandre-Étienne Choron (the boy made the ten-mile journey from home to Rheims and back each week on foot). When the Paris Conservatoire accepted Théodore as a student in 1853, it was the mayor of Rosnay, the Viscount de Breuil, who supplied the necessary funds (prompted by Théodore’s grandfather, a teacher who also served as secretary in the mayor’s office). While holding organ posts at Les Invalides and Sainte Clotilde, Dubois embraced studies with Antoine François Marmontel (piano), François Benoist (organ), François Bazin (harmony) and Ambroise Thomas (composition). Dubois graduated from the Conservatoire in 1861, having taken first prize in each of his classes. He also earned the Grand Prix de Rome with his cantata Atala, of which the Revue et Gazette musicale wrote: The cantata of M. Dubois is certainly one of the best we have heard. The poetic text of Roussy lacked strong dramatic situations but still furnished sufficient means for M. Dubois to display his real talent to advantage. -

Spanish Local Color in Bizet's Carmen.Pdf

!@14 QW Spanish Local Color in Bizet’s Carmen unexplored borrowings and transformations Ralph P. Locke Bizet’s greatest opera had a rough start in life. True, it was written and composed to meet many of the dramatic and musical expectations of opéra comique. It offered charming and colorful secondary characters that helped “place” the work in its cho- sen locale (such as the Spanish innkeeper Lillas Pastia and Carmen’s various Gypsy sidekicks, female and male), simple strophic forms in many musical numbers, and extensive spoken dialogue between the musical numbers.1 Despite all of this, the work I am grateful for many insightful suggestions from Philip Gossett and Roger Parker and from early readers of this paper—notably Steven Huebner, David Rosen, Lesley A. Wright, and Hervé Lacombe. I also benefi ted from the suggestions of three specialists in the music of Spain: Michael Christoforidis, Suzanne Rhodes Draayer (who kindly provided a photocopy of the sheet-music cover featuring Zélia Trebelli), and—for generously sharing his trove of Garciana, including photocopies of the autograph vocal and instrumental parts for “Cuerpo bueno” that survive in Madrid—James Radomski. The Bibliothèque nationale de France kindly provided microfi lms of their two manu- scripts of “Cuerpo bueno” (formerly in the library of the Paris Conservatoire). Certain points in the present paper were fi rst aired briefl y in one section of a wider-ranging essay, “Nineteenth-Century Music: Quantity, Quality, Qualities,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 1 (2004): 3–41, at 30–37. In that essay I erroneously referred in passing to Bizet’s piano-vocal score as having been published by Heugel; the publisher was, of course, Choudens. -

Castil-Blaze (1784-1857)

1/17 Data Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) Pays : France Langue : Français Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Cavaillon (Vaucluse), 01-12-1784 Mort : Paris (France), 11-12-1857 Activité commerciale : Éditeur Note : Musicographe, compositeur, librettiste et traducteur de livrets. - Critique musical au "Journal des débats" (1822-1832). - Éditeur de musique (à partir de 1821) Domaines : Musique Autres formes du nom : Castil- Blaze (1784-1857) François-Henri-Joseph Blaze (1784-1857) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 2098 8181 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) : œuvres (500 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres textuelles (150) Lettres à Émilie sur la musique (1840) De l'opéra en France (1820) Voir plus de documents de ce genre Œuvres musicales (280) Dieu que j'adore À l'aventure (1857) (1857) L'embuscade et le combat L'attente de l'ennemi (1857) (1857) data.bnf.fr 2/17 Data Benedictus. Voix (3), orgue. La majeur Le vin de l'étrier (1857) (1857) L'harmonica La chasse (1857) (1857) Chanson de Roland La marquise de Brinvilliers (1856) (1831) "Anna Bolena" "Anna Bolena" (1830) (1830) de Gaetano Donizetti de Gaetano Donizetti avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Traducteur avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Auteur du texte "Moïse et Pharaon" La forêt de Sénart (1827) (1826) de Gioachino Rossini avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Arrangeur "Oberon. J 306" "Oberon. J 306" (1825) (1825) de Carl Maria von Weber de Carl Maria von Weber avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Auteur de la réduction musicale avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Traducteur "Oberon. J 306" La fausse Agnès (1825) (1824) de Carl Maria von Weber avec Castil-Blaze (1784-1857) comme Auteur du texte "Euryanthe. -

Benjamin Godard Sonates Pour Piano Et Violon Benjamin Godard (1849-1895)

Nicolas Dautricourt Dana Ciocarlie Benjamin Godard Sonates pour piano et violon Benjamin Godard (1849-1895) CD1 CD2 Sonate pour piano et violon no 3 Sonate pour piano et violon no 4 en sol mineur, op. 9 en la bémol majeur, op. 12 Piano & Violin Sonata No. 3 in G minor Piano & Violin Sonata No. 4 in A-flat major 1. Allegro moderato 8’41 1. Vivace ma non troppo 7’53 Enregistré à la Salle Byzantine du Palais de Béhague (Paris) du 2 au 4 septembre 2015. 2. Scherzo (non troppo vivace) 3’58 2. Allegro vivace ma non presto 4’10 Remerciements : Palazzetto Bru Zane, l’équipe de l’Ambassade de Roumanie en République Française 3. Andante 4’50 3. Andante 7’02 et Pierre Malbos. 4. Intermezzo 4. Allegro molto 6’47 Production exécutive et son : Little Tribeca (un poco moderato) 2’57 Direction artistique et ingénieur du son : Clément Rousset 5. Allegro 5’26 Piano CFX YAMAHA no 6315200 Sonate pour piano et violon no 2 Préparation et accord : Pierre Malbos Sonate pour piano et violon no 1 en la mineur, op. 2 Photos artistes © Bernard Martinez en do mineur, op. 1 Piano & Violin Sonata No. 2 in A minor Piano & Violin Sonata No. 1 in C minor 5. Andante - Allegro Couverture © Bnf English translation © Sue Rose 6. Andante-Allegro 5’32 vivace e appassionato 7’16 7. Scherzo (molto moderato) 3’00 6. Intermezzo (vivace) 2’02 Aparté · Little Tribeca 8. Andante 4’59 7. Andante quasi adagio 4’16 1, rue Paul Bert 93500 Pantin, France AP124 © ℗ Little Tribeca - Palazzetto Bru Zane 2015 9.