REMINDERS from VOEGELIN and MORGENTHAU Greg Russell Univ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Volume 16: Order and History, Volume III, Plato and Aristotle

The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Volume 16: Order and History, Volume III, Plato and Aristotle Dante Germino, Editor University of Missouri Press the collected works of ERIC VOEGELIN VOLUME 16 ORDER AND HISTORY VOLUME III PLATO AND ARISTOTLE projected volumes in the collected works 1. On the Form of the American Mind 2. Race and State 3. The History of the Race Idea: From Ray to Carus 4. The Authoritarian State: An Essay on the Problem of the Austrian State 5. Modernity without Restraint: The Political Religions; The New Science of Poli- tics; and Science, Politics, and Gnosticism 6. Anamnesis 7. Published Essays, 1922– 8. Published Essays 9. Published Essays 10. Published Essays 11. Published Essays, 1953–1965 12. Published Essays, 1966–1985 13. Selected Book Reviews 14. Order and History, Volume I, Israel and Revelation 15. Order and History, Volume II, The World of the Polis 16. Order and History, Volume III, Plato and Aristotle 17. Order and History, Volume IV, The Ecumenic Age 18. Order and History, Volume V, In Search of Order 19. History of Political Ideas, Volume I, Hellenism, Rome, and Early Christianity 20. History of Political Ideas, Volume II, The Middle Ages to Aquinas 21. History of Political Ideas, Volume III, The Later Middle Ages 22. History of Political Ideas, Volume IV, Renaissance and Reformation 23. History of Political Ideas, Volume V, Religion and the Rise of Modernity 24. History of Political Ideas, Volume VI, Revolution and the New Science 25. History of Political Ideas, Volume VII, The New Order and Last Orientation 26. -

Aristotle and Plato on Friendship by John Von Heyking

Digital Commons @ Assumption University Philosophy Department Faculty Works Philosophy Department 2017 The Form of Politics: Aristotle and Plato on Friendship by John Von Heyking Nalin Ranasinghe Assumption College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/philosophy-faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Ranasinghe, N. (2017). The Form of Politics: Aristotle and Plato on Friendship by John Von Heyking. International Political Anthropology 10(1): 39-55. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Assumption University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Department Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Assumption University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Form of Politics: Aristotle and Plato on Friendship by John Von Heyking Nalin Ranasinghe Abstract Heyking’s ascent from Aristotle to Plato implies that something Platonic was lost in Aristotle’s accounts of friendship and politics. Plato’s views on love and soul turn out to have more in common with early Christianity. Stressing differences between eros and thumos, using Voegelin’s categories to discuss the Platonic Good, and expanding on Heyking’s use of Hermes, I show how tragic culture and true politics can be further enhanced by refining erotic friendship, repudiating Augustinian misanthropy, positing minimum doctrines about soul and city, and basing reason on Hermes rather than Apollo. Keywords: Plato, Aristotle, Voegelin, Eros, Thumos, friendship, soul, Von Heyking Introduction John von Heyking’s book on friendship is as easy to read as it is hard to review. -

Augustine's New Trinity: the Anxious Circle of Metaphor

Augustine’s New Trinity The Anxious Circle of Metaphor* by Eugene Webb University of Washington Augustine of Hippo (354–430) would hardly have been pleased to hear himself described as an innovator. Like any other Church leader of his time, he would certainly have preferred to be thought of as a voice of the Church’s tradition rather than an originator of any aspect of it. Recent scholarship, however, has come increasingly to see him as the source of some of the most distinctive features of the Western Christian tradition. He is now recognized not only as the originator of the doctrine of Original Sin and the peculiarly western interpretation of the doctrine of the Trinity, but also as a major force in shaping for subsequent generations of Christians the relationship between the Church’s spiritual role and its role as a power in the social and political world. With this recognition of the innovativeness of Augustine’s thought has also come the question of how his original contributions are to be evaluated. How well, for exam- ple, did he understand the tradition he was trying to interpret? How well considered were his innovations? Did they introduce not only new perspectives, but perhaps also distortions of the tradition? Elaine Pagels, for example, in her recent book, Adam, Eve, and The Serpent, has said, regarding the influence of his doctrine of Original Sin: “Augustine would eventually transform traditional Christian teaching on free- dom, on sexuality, and on sin and redemption for all future generations of Christians. Where earlier generations of Jews and Christians had once found in Genesis 1–3 the affirmation of human freedom to choose good or evil, Augustine, living after the age of Constantine, found in the same text a story of human bondage.”1 She describes this as a “cataclysmic transformation in Christian thought” (Ibid.) and suggests that it is time Augustine’s distinctive contributions in this area were reexamined and reevalu- ated. -

The Political Views and Political Legacies

Philosophical Radicals and Political Conservatives: The Political Views and Legacies of Eric Voegelin and Leo Strauss Remarks by Robert P. Kraynak, Colgate University APSA Panel, “Roundtable on Strauss and Voegelin” September 4, 2010 at 4:15pm, Washington, D. C. I. Introduction: Voegelin and Strauss were scholars in the field of political philosophy, yet they did not have an explicit political teaching. They wrote books about the great political philosophers of the past in order to learn lessons that might become living truths for today. But they did not write political treatises, defending a political ideology, for example, conservatism or liberalism, or a specific regime, such as liberal democracy or ancient Sparta or constitutional monarchy. Aside from early writings or occasional statements, their books do not contain a specific political doctrine.1 Nevertheless, their approach to philosophy is essentially “political” (rather than metaphysical or epistemological or ethical in the narrow sense). And they are widely regarded today as “conservatives,” with students and followers who are prominent conservatives of one kind or another. For example, Voegelin‟s legacy is carried on by scholars such as, John Hallowell, Ellis Sandoz, and David Walsh who defend the religious basis of the American founding and the Christian basis of liberal democracy. Strauss‟s legacy is carried on by a variety of followers – by Jaffaites defending the natural rights doctrine of the Declaration and Lincoln, by Mansfield defending the Aristotelian basis of politics, -

Rousseau in the Philosophy of Eric Voegelin

ROUSSEAUINTHEPHILOSOPHYOFERICVOEGELIN CarolinaArmenteros EricVoegelin’srelativesilenceonRousseauisstriking. 1Inthewholeofhiscorrespondence, and in the thirty-four volumes of his collected works, less than a dozen passages refer to Rousseau,andonlyahandfulofthese–comparativelyshort–engagewithhisthought.Given Rousseau’stoweringstatureinthehistoryofphilosophy,andconsideringVoegelin’sprojectto synthesizeWesternthoughtfromantiquitytothepresent,onewondersattheimmensityof suchindifference.Thisisespeciallythecasewhenconsideringthatopportunitiestocomment kept presentingthemselves. Strauss, most notably, mentionedRousseauseveral times in his letterstoVoegelin,butitwasonlywhenhehadtorespondtoStrauss’sarticle,“TheIntention ofRousseau,”thattheAustrianfinallywrotebackwithsomereflectionsontheGenevan.And even then, those reflections were not so much on Rousseau’s thought proper, as on its similaritywithVico’s.2 Why so much reticence? In The Voegelinian Revolution , Ellis Sandoz observes that Voegelin associated Rousseau with the rise of the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth centuryevenbefore J.L. Talmonwrote TheOriginsof TotalitarianDemocracy (1952).3Thisfact couldhelpexplainVoegelin’ssilencebecausetotalitarianismwasavitalsubjectforhim.After all, his whole life’s work arose froma dual impulse: to explain the totalitarian movements whoserisecausedhisflightfromEurope,andtoreforgeandrevalorizephilosophysoasto 1 I amgrateful to TJohnJamiesonfor havingbroughtthis factto myattention, andsuggestedthe subjectofthispaper. 2LeoStraussandEricVoegelin, FaithandPoliticalPhilosophy:TheCorrespondencebetweenLeoStraussandEric -

Eric Voegelin's Theory of Intentionality in Consciousness and Its Pragmatic

BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ERIC VOEGELIN’S THEORY OF INTENTIONALITY IN CONSCIOUSNESS AND ITS PRAGMATIC INFLUENCES A DISSERTATION PROSPECTUS SUBMITTED TO THE DIVISION OF RELIGIOUS AND THEOLOGICAL STUDIES STEPHEN PROTHERO, CHAIR BY GREGORY D. FARR BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS JANUARY 2005 FIRST READER: ROBERT C. NEVILLE, Ph.D. SECOND READER: RAY L. HART, Ph.D. This dissertation offers an analysis of the impact of the American pragmatist tradition on the philosophical thought of the twentieth century political theorist, Eric Voegelin. It argues that Voegelin‟s early-career encounters with the thought of the classical American pragmatists shaped the tendency and organization of his philosophical methodology and that Voegelin‟s philosophical vision is significantly clarified when conceived in relation to this intellectual source. To make this case, this project focuses primarily on the influence of William James‟ philosophy on Voegelin‟s theory of consciousness and the treatment of other persistent themes developed throughout Voegelin‟s extensive writings that explicitly engage American pragmatist theory. The problem addressed directly within this examination concerns the ambiguous character of Voegelin‟s understanding of intentionality in consciousness, which has been exposed by recent scholarship examining Voegelin‟s philosophy. The issue of intentionality of consciousness for Voegelin, at one level, is quite similar to Husserl‟s understanding of the structural fact of consciousness as always involving an awareness of something. Hence Voegelin often refers to intentionality as the way consciousness, at least insofar as it may be known in human experience, both interacts with and is embodied in empirical concrete existence. This connotation of intentionality, for Voegelin, however, is viewed in a subordinate role to his notion of the “luminosity of consciousness”, which refers to consciousness as the “site” or “sensorium” of human participation in its encompassing reality. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Providential Nature

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Providential Nature of Politics in the Thought of Jonathan Edwards A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Coyle B. Neal Washington, D.C. 2012 The Providential Nature of Politics in the Thought of Jonathan Edwards Coyle Neal, Ph.D. Director: Claes Ryn, Ph.D. Despite the obvious importance of Jonathan Edwards in American history, scholars have largely ignored his relevance for political thought. To ignore him is to miss a critical component in early American political philosophy and to have a skewed understanding of the subsequent history of revivals and revivalism that have shaped religion, politics, and philosophy in America. This dissertation addresses this oversight. It situates Edwards among American political thinkers and shows him to be an important piece in the American political tradition. This dissertation argues that for Jonathan Edwards politics is deeply historical in nature. He has a strong historical sense that is indistinguishable from his notion of Providence. The dissertation concludes that—in line with his theology, ethics, aesthetics, and metaphysics—the political philosophy of Jonathan Edwards is fundamentally historical and more akin to that of Burke, Hegel, Adams and other “conservative” thinkers than it is to Rousseau, Paine, and other revolutionary thinkers. The dissertation examines Edwards’ own writings as well as important secondary sources and interpretations of his work. It uses a traditional hermeneutical technique to systematize his social and political ideas and to draw out implications for political thought from his ostensibly non-political theological and philosophical writings. -

A Consideration of the Philosophical Insights Of

A CONSIDERATION OF THE PHILOSOPHICAL INSIGHTS OF ERIC VOEGELIN: THE LIFE OF REASON, THE EQUIVALENT SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HUMAN ENCOUNTER A dissertation by Claire Rawnsley, B.A.Hons. Submitted in fulfilment of PH.D in the Department of History, University of Queensland July 1998 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have in various ways I have been kind enough to read and give advice regarding this thesis. First, I would thank the various lecturers in the History Department at University of Queensland who have assisted my work on this thesis from the beginning. There is Professor Paul Crook, Dr. John Moses, my supervisors, and also Dr. Martin Stuart-Fox who have all offered important criticism of my work. I would also like to thank those people whom I contacted in the Voegelin society, in particular, Dr. Geoffrey Price. He has generously offered many valuable suggestions and provided points that have had an important bearing of the thesis. I would also like to thank Mr. Mike Dyson who introduced me to the complexity of the world of Plato and Aristotle and gave me critical points to consider in that area. There are many others who have helped with the typing and editing of the several drafts. First there is Mrs. Irene Saunderson who typed the first draft of my thesis before I acquired some computer expertise. Then there is Ms. Robin Bennett who painstaking edited the draft and also Mrs.Mary Kooyman who kindly offered many valuable suggestions with the presentation and final editing. I would also like to thank Mrs.Rosemary van Opdenbosch who generously translated several articles from French and German. -

Voegelin and Aristotle on Noesis Copyright 2000 David D. Corey

Voegelin and Aristotle on Noesis Copyright 2000 David D. Corey Since the philosopher Eric Voegelin has come under criticism as of late for his use of politics to "stamp out manifestations of deformed consciousness," the time may be right to reflect on the motivations and limits of Voegelin's work.1The limits, in particular, are sometimes difficult to keep in view while Voegelin is expounding upon the totality of being, the myriad dimensions of human consciousness, and the nature of order in personal, social and historical existence. But in fact Voegelin's work is limited-more than his magisterial tone might suggest-to offering general insights into the structure of being as opposed to offering a specifically ethical or political science. That, at any rate, is what I hope to make clear in the pages that follow. And if I am right in this regard, a consequent fact will be that Voegelin stands unfairly accused if he is accused of using politics for much of anything at all; for while his investigation of the structure of being may supply grounds for a philosophical critique of various ideological programs, it certainly does not itself supply a starting point for political action. Another way of saying this is that Voegelin does not offer his readers a substantive ethical or political theory-one that, like Aristotle's, considers the question of human action in particular with an eye to being useful.2 Now to seasoned readers of Voegelin this limit to his work may seem obvious, but no one to my knowledge has bothered to discuss it in writing. -

Register of the Eric Voegelin Papers, 1907 – 1997

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4m3nb041 No online items Register of the Eric Voegelin Papers, 1907-1997 Processed by Linda Bernard; machine-readable finding aid created by Hernán Cortés Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Eric Voegelin 1 Papers, 1907-1997 Register of the Eric Voegelin Papers, 1907-1997 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Processed by: Linda Bernard Date Completed: 1988 Date Revised: 1997 Encoded by: Hernán Cortés © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Eric Voegelin Papers, Date (inclusive): 1907-1997 Creator: Voegelin, Eric, 1901- Extent: Number of containers: 128 ms. boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 5 card file boxes, 2 envelopes. Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, reports, memoranda, conference proceedings, and printed matter, relating to the philosophy of history, the philosophy of science, various other aspects of philosophy, and to political science and other social sciences, especially as considered from a philosophical perspective. Most of collection also on microfilm (101 reels). Language: English and German. Access The collection is open for research except for box 138, which is closed until 2017 June 11. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Eric Voegelin Papers, [Box no.], Hoover Institution Archives. -

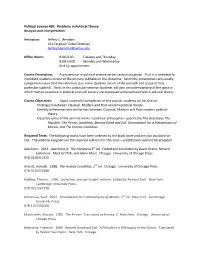

Political Science 489: Problems in Political Theory Analysis and Interpretation

Political Science 489: Problems in Political Theory Analysis and Interpretation Instructor: Jeffrey C. Herndon 162 Ferguson Social Sciences [email protected] Office Hours: 8:00-9:30 Tuesday and Thursday 8:00-10:00 Monday and Wednesday And by appointment. Course Description: A proseminar in political science serves several purposes. First it is intended to introduce students to one of the primary subfields in the discipline. Secondly, proseminars are usually comprehensive in that the intention to is make students aware of the breadth and scope of that particular subfield. Third, in this particular seminar students will gain an understanding of the ways in which human existence in political and civil society are expressed and examined within political theory. Course Objectives: Upon successful completion of this course, students wil be able to:: Distinguish between Classical, Modern and Post-modern political theory. Identify differences and similarities between Classical, Modern and Post-modern political theory. Describe some of the seminal works in political philosophy—specifically The Orestaeia, The Republic, The Prince, Leviathan, Beyond Good and Evil, Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, and The Human Condition. Required Texts: The following books have been ordered by the book store and are also available on- line. The editions assigned are the required editions for this class—substitutions will not be accepted. Aeschylus. 2013. Aeschylus II: The Orestaeia,3rd ed. Edited and translated by David Grene, Richard Lattimore, Mark Griffith, and Glenn Most. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 978-0226311470 Arendt, Hannah. 1998. The Human Condition, 2nd ed. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 978-0226025988 Hobbes, Thomas. -

Investigating the Silence Surrounding

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS GOLDEN: INVESTIGATING THE SILENCE SURROUNDING THE TIIOUGHT OF ERIC VOEGELIN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DMSON OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE MAY 2008 By Patrick Johnston Thesis Committee: Manfred Henningsen, Chairperson JamesDator Louis Hennan We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As the experience which engendered this project occurred during my time as an undergraduate at Louisiana State University, I should begin to acknowledge my debts by stating my appreciation of the Triumvirate (Professors Cecil Eubanks, Ellis Sandoz and James Stoner) for keeping political philosophy alive at LSU and for helping me build a foundation in the philosophical science of politics. Dr. Sandoz, who introduced me to Eric Voegelin's work, deserves special commendation for his tireless-work in promoting Voegelin's thought. His dedication in this endeavor has made my work in the following pages much easier than it might have been otherwise. I would be remiss if I did not include among my benefactors at LSU Professor Harry Mokeba who was instrumental in showing me the importance of comparative political study. In this vein I should add Dr. Sankaran Krishna who has continued to foster my interest in comparative political analysis during my graduate studies in Hawai'i. I extend my utmost gratitude to my committee, which included Professors Manfred Henningsen, James Dator and Louis Herman.