Streamliners Program Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By GRACE FLAN- Railway Company, Fort Union and Its Neighbors on The

Fort Union and Its Neighbors on the Upper Missouri 303 Cook, Meares and Vancouver. No claim is made to a presenta tion of new material but the new arrangement makes available in convenient and inexpensive form a connected account of events in the early history of the North Pacific Coast. The book is well illustrated and contains seven maps. It is particularly well adapt ed to school use but is worthy of a place in libraries, public or private. Five tales of maritime adventure from log books and orginal narratives compose the volume entitled The Sea} The Ship, and the Sailor. Two are of special interest to students of the Pacific Northwest. One of these is a reprint of The Life and Adventures of John Nicol (Edinburgh, Blackwoods, 1822) a rare volume growing out of the voyage of Portlock and Dixon. The other is the first printing of a manuscript entitled : Narrative of Events in the Life of John Bartlett of Boston, Massachusetts, in the years 1790-1793} During Voyages to Canton and the Northwest Coast of North America. The narrative gives new information and its value is enhanced by notes supplied by his honour, Judge F. W. Howay. CHARLES W. SMITH. Fort Union and Its Neighbors on the Upper Missouri. By FRANK B. HARPER. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Com pany, 1925. Pp. 36.) A Glance at the Lewis and Clark Expedition. By GRACE FLAN DRAU. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Company, 1925. Pp.29.) An Important Visit, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, 1805. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Company, 1925. -

![1919-12-16 [P 15]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2615/1919-12-16-p-15-392615.webp)

1919-12-16 [P 15]

" boxing | mmm RIAN MEE'IS BILL} Windsor Five Here For The Melting Pot PAGER BIG HIE THOMPSON THURSDAY Return Tomorrow Sport News Boiled Down Game vs. Another card of fights has been ar- Colby Mick. will The following has been received But our man was game, if nothing ranged for Lhe Amboy Sporting Club The six round semi-final event who Colby of Chroma Fein DEFEAT from a fight fan of the fair sex. else on Thursday night, and the prog'im bring together young and KEPPGRT Tha basketball fans will thmong to around team work. Schelling seems to be quute a backer of the And still came up for more. will consist of one e ftht, one six nd and Henry Mick of I3rookIyn. Colby the Auditorium Court tomorrow night fast men a dead ot will be the forwards, two "iia.be Ruth of boxing" Al Roberta. three four round bouts. has been meeting with great to see the Windsor Big Five and the The Pacer Big Five of this city local w'ho have In wonderful “To AL” But he is only Just a kid Hyan vs. TIumipHon. success in the ring, having ap- team action for pttfortned traveled to last night, where local Auditorium in Keyport, h.m a to learn. the peared in preliminaries and scmL-flnal the local court already this There was a young fellow Let's give chance In the main event. Willie Hyan. the second time this season, the first style on they defeated the Aero Flyers of that all around box- His first naano was Al And u hen ho gets experience fc.st climbing vvel'er of New Bruns events. -

Mark Williams' Presentation California Zephyr

Three Railroads 2532 Miles Of Gorgeous Scenery Five Vista Domes The Most Talked About Train In America... Silver Thread to The West The History of the California Zephyr March 20, 1949 -March 20, 1970 Beginnings 1934 Pioneer Zephyr Streamlined Ralph Budd (CBQ) meets Edward Budd (Budd Corp.) Stainless steel and shotwelding Wildly successful = willing to take risks Beginnings Exposition Flyer – 1939 First through car train for CB&Q/DRGW/WP “Scheduling for Scenery” Dotsero Cutoff / Moffat Tunnel Traded time & distance for scenic beauty CZ Fun Fact #1 Beginnings 1940 Joint Meeting 1943 Informal Discussions Post-war RR's Awash With $ October 1945 Joint Contract First orders to Budd 1945 Revisions in 1946 & 1947 First deliveries 1948 Beginnings 1944 Cyrus Osborn's (General manager of EMD) grand idea 1944 trip Glenwood Canyon The Dome Car is born by rebuilding a standard Budd chair car (originally Silvery Alchemy) CZ Fun Fact #2 Dividing The Cost And Costs were dividedProfits by percentage of CZ route mileage (the Exposition Flyer route) CB&Q = 41% DRGW = 22% WP = 37% Profits were divided by percentage of short line route (the Overland Route), which cost WP 10% compared to CB&Q and DRGW share Dividing The Cost And Profits CB&Q owned 27 cars DRGW owned 15 cars WP owned 24 cars PRR leased 1 car Planning Menus Timing Governed by need to have the train in the Rockies and Feather River Canyon during daylight Layover time for through car was a casualty Staffing The Zephyrettes CZ Fun Fact #3 The Zephyrettes Planning -

OSTESSES and Trios of Hawa.Iian Guitar Players Comfort and Entertain

16 THE SATURDAY EVENING POST Octob.,. 17.10.,6 o o or • OSTESSES and trios of Hawa.iian guitar discomfort as well: the B. & O. began to air-condition, on railroad tracks. The Bul"iington long had been players comfort and entertain passengers to starting with a dining car. That was in 1930. using single gas-8ngine cars to give more frequent Florida. A daily train between Cleveland and \Vhen the Century of Progress Exposition began service on its secondary lines, The maker or the Detroit is transformed and its running time short in Chicago, in the summer of 1933, the B. & O. had rubber-tired cars was the Edward G. Budd Manufac ened; its cars become as lively and alluring as the about 125 air-conditioned cars in operation on the turing Company, of Philadelphia. Ralph Budd and decks of a transatlantic liner on a week-end cruise; it numerous sections of the Capitol Limited, running Edward are not kinsmen, and tltis was their first has a restaurant as smart as any in a first-class botel. between New York and Crucago by way of Washing meeting. The railroad president was not convinced with divans and half-moon tables; kitchen and ton. At the same time on the Chicago run from that pneumatic tires were as yet practical for use on smells are in another car. Lately a railroad president Southern gateway cities the air-conditioned George the railroads, but Edward Budd, a lifelong worker in has been East with the eqillvalent of a million dollars Washington. of the Chesapeake & Oruo, was attract metal, set to ·work to make rum see that the metal of in each hand to pay for a pair of streamlined Zephyrs ing swarms of passengers from its non-air-conditioned those cars was important. -

Page 11 California Zephyr and the Other Looking at the “Zephyrette

Issue 181 - April/May/June 2019 The Train Sheet (Convention...continued from front cover) California Zephyr and the other and WP focus worked well and both groups looking at the “Zephyrette” Rail complemented each other, a fact also shown in Diesel Cars. the high number of attendees who hold joint • A showing of Virgil Staff Films from membership in both organizations. At final the FRRS archives focusing on the count, about 265 people registered to attend. California Zephyr Janet Dawson and Jeff Asay also held book I want to thank Steve and Mary Habeck, Greg signings at the WPRM Museum Store table. Elems, Kerry Cochran, Scott McAllister, Jim Janet’s Zephyr mysteries and Jeff’s book “The Iron Collins, Cathy Von Ibsch, Paul Finnegan, Frank Feather” were big sellers, along with a special Brehm and all the PCR folks who helped make 70th Anniversary CZ publication reprinting the convention happen. Thanks to Eric McKay material from long out of print Headlights 17 and for good food and moral support. And huge 18. This was put together in time for the thanks to all the presenters! Everyone did convention by Paul Finnegan and the archives fantastic jobs on their shows. department volunteers with special thanks to I have decided that this will be the final Frank Brehm. convention I coordinate as there are several Several of the modeling and photography other projects on the horizon that will demand presentations also paid homage to the Western my attention, so let me take this opportunity to Pacific, including Neil Fernbaugh, whose Hands- thank everyone who has helped me with On Weathering clinic featured photos of WP planning and execution of the WP conventions prototypes for inspiration. -

Ralph Modjeski by Frank Griggs, Jr., Dist

Great achievements notable structural engineers Ralph Modjeski By Frank Griggs, Jr., Dist. M. ASCE, D. Eng., P.E., P.L.S. odjeski, (ne. Rudolphe his assistant. He then went into partnership could not agree on a Modrzejewska) was born in for a short time with J. F. Nickerson, followed specific recommen- Cracow, Poland on January 27, by his becoming Chief Engineer on a Bridge dation, as Vautelet 1861. His mother was an inter- across the Mississippi River at Rock Island. recommended one of Mnationally known actress who encouraged him It was the fourth bridge at this site and was a the tenders on his own Ralph Modjeski to become a concert pianist. But, at an early age, seven span railroad and roadway bridge with design and Macdonald he determined he would become a civil engineer. a swing span over a set of locks. and Modjeski recommended a design by the St. His family came to the United States to attend In 1902, Modjeski went into partnership Lawrence Bridge® Company. Vautelet left the the Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia and with Alfred Noble forming the firm of Noble Board and was replaced by Lt. Col. Charles start an orange farm near Anaheim, California. and Modjeski with one of their largest proj- Monsarrat and Macdonald was replaced by C. His mother continued her acting career and ects being a cantilever across the Mississippi at C. Schnieder (STRUCTURE, January 2011). Modjeski attended schools in the San Francisco Thebes, Illinois. After this bridge was finished, It was these three engineers who oversaw the area for a short time. -

Congressional Record-Senate Senate

1650 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE JANUARY 31 municipalities, and school districts can be financed directly ness of the company, together with a list of stockholders, by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation; to the Com for the year ended December 31, 1933, which, with the ac mittee on Banking and Currency. companying papers, was referred to the Committee on the 1970. By Mr. PERKINS: Letter from Charles V. Bacon, District of Columbia. Mahwah, N.J., opposing the excise tax on coconut oil; also REPORT OF THE GEORGETOWN GASLIGHT CO. telegram from William King, Hohokus, N.J., opposing excise As in legislative session, tax on coconut oil and other imported oils; and a telegram The VICE PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a letter from Albert Grundy, River Edge, N.J., opposing excise tax on from the vice president of the Georgetown Gaslight Co., coconut oil and copra; to the Committee on Ways and transmitting, pursuant to law, a detailed statement of the Means. business of the company, together with a list of stockholders, 1971. By Mr. RUDD: Petition of Munay & Flood, New for the year ended December 31, 1933, which, with the ac York City, favoring the passage of House bill 5632; to the companying papers, was refened to the Committee on the Committee on Agriculture. District of Columbia. 1972. By Mr. STRONG of Pennsylvania: Petition of Woman's Christian Temperance Union of Indiana County, REPORT OF THE CHESAPEAKE & POTOMAC TELEPHONE CO. Pa., favoring enactment of House bill 6097, to regulate the As in legislative session, motion-picture industry; to the Committee on Interstate and The VICE PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a letter Foreign Commerce. -

NEWSLETTER See Our Web Page at May 2006

NEWSLETTER See our Web page at http://www.rcgrs.com/ May 2006 A Note from the Barbara for hosting that fun--filled afternoon at Vice--President Jeff Lange your wonderful home in Vancouver! Our next open house/business meeting is on Satur- Dear Members of the RCGRS: day, May 13th, at Dennis and Carolyn Rose’s home. I am writing this message this month to help out our Please check the newsletter for times and what to club President, whose father just passed away. I am bring for lunch. happy to help any club member out at anytime, and Member Roster: Some members have not paid their I was happy to fill in for Darrel at this time. Please dues for 2006. We still want them to remain mem- send him your regards and condolences for the loss bers of our club, and to please submit their annual of his father. Darrel has been by his dad’s side for dues to the treasurer, Steve Cogswell, as soon as the last month or so, and was with him right to the possible. Only those who have paid their current very end. dues will have access to the member’s area of the Website and will continue receiving the Newsletter. In the meantime, we have had two great open houses just recently, and I was fortunate enough to Diesel Engines of 1930 have been able to attend both. The first one was held at Quinn Mountain, on the afternoon of The Electro--Motive Corporation (EMC) was Sunday, March 26th. Both Christina and Bud put on created by Harold Hamilton in 1924. -

SIA Newsletter (SIAN)

Volume 35 Summer 2006 Number 3 LITTLE-KNOWN WATT STEAM ENGINE IN AMERICA In Winter 2003, the SIAN ran a query from the Somerset Henry Ford, however, was not the only American entre- (U.K.) Industrial Archaeological Society seeking information on preneur whose interest in innovation led him to have a his- a Watt rotative beam engine that was believed to have been toric Watt engine shipped to this country. In 1957, shipped to America after WWII. R. Damian Nance [SIA] rec- Leighton A. Wilkie, founder of the DoALL Co. in Des ognized the engine as one displayed in the headquarters of the Plaines, IL (just west of Chicago), purchased a rotative DoALL Co. in Des Plaines, IL. He has since done exhaustive beam engine from the Holyrood (lace) Mill of Gifford, Fox research on the engine and submits the following report. & Co., in Chard, Somerset, U.K. Like Ford, Wilkie was interested in the role of industrial enterprise in American he Soho Works of Matthew Boulton and James prosperity. To illustrate the importance of innovation in Watt in Birmingham, England, played such a machine tools that he felt his company exemplified, he pivotal role in the course of the Industrial established a “Hall of Progress” at the company headquar- TRevolution that Henry Ford, in connection ters in 1958-59. The centerpiece of this now-dismantled with his interest in invention, had two of their museum was a giant sunburst, the rays of which symbolized innovative steam beam engines (built in 1796 and 1811) “the 10 broad mainstreams of human activity that, togeth- shipped to his museum in Dearborn, MI, following a visit to er, have created the modern age of abundance.” Britain in 1929. -

Mr. Budd's Historical Expeditions

Mr. Budd’s Historical Expeditions Randal O’Toole n 1925 and 1926, the Great North- ern Railway sponsored two trips Iunlike any rail tours before or since. In preparation, the railway erected six historic monuments that remain to this day, commissioned numer ous papers on the history of the Northwest, convinced the U.S. Post Office to rename several places newspaper publishers and writers. he said. “The country distinctly has a so as to reflect their history, and in- Though the ostensible purpose was past and a great many stirring things vited prominent historians, state gov- to study agricultural conditions, the happened many years before what we ernors, a former chief of staff of the group passed the Chief Joseph Battle- call our present civilization came here U.S. Army, and a U.S. Supreme Court field in Montana and spent time in at all.”3 This was Budd’s vision for the justice to give talks at various points Glacier National Park and Seaside, Upper Missouri Historical Expedition along the way. Oregon, giving Budd the opportunity that would go from St. Paul to Glacier These tours were the brainchild to point out numerous historic sites Park in July 1925, stopping at a wide of Great Northern president Ralph along the way.2 variety of historic sites along the way. Budd. An Iowa farm boy who received While Glacier and Seaside offered Budd’s objective, at least in part, his degree in civil engineering at the unforgettable scenery, Budd realized was to attract passengers to his rail- age of 19, Budd was a self- made intel- that many travelers thought the Great road. -

Document (PDF)

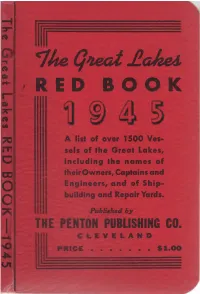

The Great Lakes RED Great The —BOOK RED Lakes 5 194 * 7 < 4 e Q n& at J t a h & i R E D B O O K A list of over 1500 Ves sels of the Great Lakes, including the names of their Owners, Captains and Engineers, and of Ship building and Repair Yards. Published by THE PENTON PUBUSNINC CO. CLEVELAND P R I C E ...................................$ 1 .0 0 3 IN THESE GREAT LAKES PORTS We Offer You Complete G-E Service • BUFFALO Sales Offices 1 West Genesee Street Service Shop: 318 Urban Street • CHICAGO Sales Office: 840 So. Canal Street Service Shop: 849 So, Clinton Street • CLEVELAND Sales Office: 4966 Woodland Avenue Service Shop: 4966 Woodland Avenue • DETROIT Sales Office: 700 Antoinette Street Service Shop: 5950 Third Avenue • MILWAUKEE Sales Office: 940 West St. Paul Avenue Service Shop: 940 West St. Paul Avenue IWarehouse stocks maintained in a ll the above Great Lakes Ports • DULUTH Sales Office: 14 West Superior Street • TOLEDO Salts Office: 420 Madison Avenue BUILDERS OF MARINE EQUIPMENT SINCE 1892 GENERAL ELECTRIC t,h»*No 9*00 m SCHENECTADY, N. Y. VESSELS OF T H E GREAT LAKES with the name of ANCHOR CHAIN OWNER, CAPTAIN AND ENGINEER And + Complete Port Directory JOINING LINKS Complete Shipyard Directory Dimensions and Capacity of Assure Extreme Bulk Freighters Strength A nd + Durability 1945 ______ SEASON mam i c < mmmm solid V NATIONAL MALLEABLE AND Published by STEEL CASTINGS COMPANY THE PENTON PUBLISHING CO. Cleveland General Offices Cleveland, Ohio 7 HOW TO USE THE DIRECTORY • ■ Beginning on page 39 is listed more than 1500 vessels available for service on Boiler water treatment and engineering the Great Lakes for the season of 1945. -

CATALOG of GIFTS 2017 / 2018 Annual Gift Magazine of The

CATALOG OF GIFTS 2017 / 2018 Annual gift magazine of the BOOKS GAMES MOVIES MORE FANTASTIC HOLIDAY GIFTS FOR EVERY RAILFAN 2018 CALENDARS 2018 McMillan Rio Grande Calendar 13.9” x 19.4” hung. $15.95 (#9105) 2018 Colorado Narrow Gauge Calendar A railfan favorite, Colorado Narrow Gauge shows the trains that once traversed the narrow gauge rails, serving the Centennial State’s mountain communities and their mines from the 1800s into the mid-1900s. 13.7” x 21.5” 2018 McMillan Union Pacific Calendar hung. $15.95 (#9031) 13.9” x 19.4” hung. $15.95 (#9106) 2018 BNSF And Its Heritage Calendar 2018 Great Trains - Paintings by 2018 Those Remarkable Trains 11” x 18” hung. $14.95 (#9032) Gil Bennett Calendar 13.7” x 21.5” hung. 13” x 21” hung. $15.95 (#9036) $15.95 (#9033) 2018 Narrow Gauge Memories Calendar 2018 Howard Fogg’s Trains Calendar 2018 Classic Trains Calendar 13” x 21” 11” x 18” hung. $14.95 (#9067) 13.7” x 21.5” hung. $15.95 (#9034) hung, B&W photos. $14.99 (#9107) 2018 Union Pacific Then & Now Calendar 2018 Santa Fe Railway Calendar 2018 Union Pacific Calendar 11” x 18” hung. $14.95 (#9068) 13.7” x 21.5” hung. $15.95 (#9035) 13” x 21” hung. $15.95 (#9037) 01 Colorado Railroad Museum Catalog 2017 / 2018 HATS & SHIRTS CLOTHING D&RGW Locomotive D&RGW Locomotive Galloping Goose Khaki Colorado Railroad Museum No. 346 Baseball Hat No. 491 Baseball Hat Baseball Hat Embroidered, Baseball Hat Embroidered, Embroidered, adjustable velcro Embroidered, adjustable Museum logo in back, adjustable velcro strap strap $25.99 (#5370) velcro strap.