Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

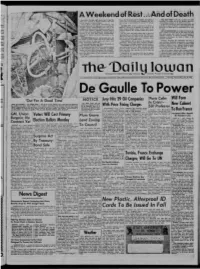

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1958-05-30

I' American Thursday nJiht headt>d into a long Me dents with 206 injurie and 7 Cat31ities, the highe t in THE HIGH POINT oC the day In citie and town morial Da)' w !tend 01 picnic , par d , auto trips r cent y ar . The 0\' r· aU ~y ar .lemori31 Day 3CCi· throughout the nation will be the parades, peechcs, and tilt! nK'Race of high 'ay deaUJ. d nt a\erag is 130 ac id nls, 65 Injured, and 3 latali· and traditional trloot to the nation' war dead. Russell Bro\\n. tale lety Commi ioner, id til' . In the We t a de troyer and na\'al patrol plane will ~rgency Iowa has joined with Ih'e other lat in a coordinated IN IOWA CITY, traffic i. expected to be h a\'y on drop flower upon lhe Paeiric. A flower·bedecked raft lurgency campai n against IraCrlC lalahli .. The crux of the lIigh 'ay 6 coming in on Dubuque l. becall.! of the was to be let adrift down 1he f ippi Ri\'er from Icra::ltdown i that if an Iowa re id nt is caught in a d tour around 0 Itdale. Abo,· normal framc is ex· Sl Louis. exeeu, mD\'ini tr me \'101 lion - din , improper in , pected on Highway 261, including Dodge tr t traffic AND IN WASHINGTON, the cask ts bearing the un· Kress ia etc., - in one of til other tate. the "iolalion will be to Solon. known Idi r oC World War II and Koren will take mem· Ireport d to the Iowa tate Saf ty Commis ion.' All city, . -

Revolutionary Reader Reminiscences and Indian Legends

REVOLUTIONARY READER REMINISCENCES AND INDIAN LEGENDS SOPHIE LEE FOSTER AMERICA 1. My Country, 'tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing; Land where our fathers died, Land of the pilgrims' pride, From every mountain side Let freedom ring. 2. My native Country, thee, Land of the noble free, Thy name I love; I love thy rocks and rills, Thy woods and templed hills, My heart with rapture thrills, Like that above. 3. Let music swell the breeze, And ring from all the trees, Sweet Freedom's song; Let mortal tongues awake, Let all that breathe partake, Let rocks their silence break, The sound prolong. 4. Our Father's God, to Thee, Author of liberty, To Thee we sing; Long may our land be bright, With Freedom's holy light, Protect us with Thy might, Great God, our King! WASHINGTON'S NAME At the celebration of Washington's Birthday, Maury Public School, District of Columbia, Miss Helen T. Doocy recited the following beautiful poem written specially for her by Mr. Michael Scanlon: Let nations grown old in the annals of glory Retrace their red marches of conquest and tears, And glean with deft hands, from the pages of story The names which emblazon their centuried years— Bring them forth, ev'ry deed which their prowess bequeathed Unto them caught up from the echoes of fame; Yet thus, round their brows all their victories wreathed, They'll pale in the light of our Washington's Name! Oh, ye who snatched fame from the nation's disasters And fired your ambitions at glory's red springs, To bask, for an hour, in the smiles of your masters, And -

By GRACE FLAN- Railway Company, Fort Union and Its Neighbors on The

Fort Union and Its Neighbors on the Upper Missouri 303 Cook, Meares and Vancouver. No claim is made to a presenta tion of new material but the new arrangement makes available in convenient and inexpensive form a connected account of events in the early history of the North Pacific Coast. The book is well illustrated and contains seven maps. It is particularly well adapt ed to school use but is worthy of a place in libraries, public or private. Five tales of maritime adventure from log books and orginal narratives compose the volume entitled The Sea} The Ship, and the Sailor. Two are of special interest to students of the Pacific Northwest. One of these is a reprint of The Life and Adventures of John Nicol (Edinburgh, Blackwoods, 1822) a rare volume growing out of the voyage of Portlock and Dixon. The other is the first printing of a manuscript entitled : Narrative of Events in the Life of John Bartlett of Boston, Massachusetts, in the years 1790-1793} During Voyages to Canton and the Northwest Coast of North America. The narrative gives new information and its value is enhanced by notes supplied by his honour, Judge F. W. Howay. CHARLES W. SMITH. Fort Union and Its Neighbors on the Upper Missouri. By FRANK B. HARPER. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Com pany, 1925. Pp. 36.) A Glance at the Lewis and Clark Expedition. By GRACE FLAN DRAU. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Company, 1925. Pp.29.) An Important Visit, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, 1805. (Saint Paul: The Great Northern Railway Company, 1925. -

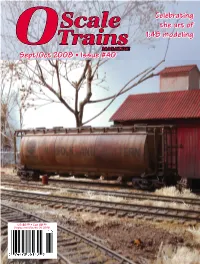

MTH DCS to DCC Conversion Changing Over an MTH Steam Loco As Detailed by Ray Grosser

Celebrating Scale the art of Trains 1:48 modeling MAGAZINE O u Sept/Oct 2008 Issue #40 US $6.95 • Can $8.95 Display until October 31, 2008 www.goldengatedepot.com / FAX: (408) 904-5849 GGD - RERUN P70s NEW CAR NUMBERS: ORDER IN PAIRS: PRR, PRSL, LIRR, $249.95 MSRP. RESERVE TODAY! VERY LIMITED QUANTITIES. RERUN PULLMAN 12-1 SLEEPERS IN ABS NEW CAR NAMES TOO: PRR, PULLMAN (GREEN), PULLMAN (TTG), ERIE (TWO TONE GREEN), LACKAWANNA (Grey and Maroon). RESERVE TODAY! COMING FALL 2008. $129.95 MSRP each. Set A: RPO/Baggage 5018 Diner 681 NYC 20th Century 1938 & 1940 4-4-2 Imperial Highlands YES WE ARE OFFERING THE 1940 STRIPING TOO! Observation Manhattan Is. Set B: Dorm/Club Century Club 17-Roomette City of Albany 10-5 Cascade Dawn 13-Double Bedroom Cuyahoga County Set C: Diner 682 17-Roomette City of Chicago Available in Late 2008 for $599.95 (RESERVE PRICE) per 4 Car Set 10-5 Cascade Glory 4-4-2 Imperial Falls 54’ STEEL REEFERS HW DINER / OBSERVATION Also: PRR - BIG CHANGE REA ORIG 4-2-1 PULLMAN OBSERVATION ACL D78br - DINER (w/3DP1 Trucks) GN B&O REA Green Pull-Green NYC SF OFFERED IN MANY OTHER ROADS WITH PULLMAN TRUCKS GGDGGD Aluminum Aluminum SetsSets -- PRICEPRICE CHANGE CHANGE - NYC ESE: 6 Car Set, 2 Car Add On ($599.95 / $299.95) FALL 2008 - Santa Fe 1937 Super Chief: 6 Car Set, 2 Car Add On ($599.95 / $299.95) FALL 2008 - Southern Pacific Daylight: 5 Car, 5 Articulated Add On ($599.95 / $599.95) Late 2008 - PRR Fleet of Mod. -

About the Pioneer Zephyr

About the Pioneer Zephyr The Pioneer Zephyr is America’s first diesel-electric, streamlined, stainless-steel passenger train. It is located in the Museum’s Entry Hall and was renovated and conserved in 2020. History In an attempt to increase rail passenger traffic, the Burlington Zephyr was built for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company (CB&Q) in 1934 by the Budd Company of Philadelphia. The Burlington Zephyr offered high-speed transportation in an elegant, streamlined, stainless steel design. It was the first diesel-electric passenger train to enter regular service. The train was renamed the “Pioneer Zephyr” in 1936 because it was the first of several diesel-powered Zephyrs built for the CB&Q. On May 26,1934, the Pioneer Zephyr left Denver and arrived in Chicago 13 hours and five minutes later to reopen the A Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1934. That single nonstop trip of 1,015 miles at record-breaking average speed of 77.6 mph changed the course of railroading and land transportation. Never before had a train traveled more than 775 miles without stopping for fuel and water. The Pioneer Zephyr, nicknamed the “Silver Streak,” was donated to the Museum of Science and Industry in 1960 and was displayed outside next to the 999 Empire State Express locomotive near the Columbia Basin. In 1997, the Museum hired Northern Rail Car of Milwaukee to restore the Pioneer Zephyr to it 1930s-era glory. The gleaming, refurbished train was then moved to a new, underground gallery at the Museum in 1998. The exhibit closed in October 2019, to make way for a completely new exhibition, opening in March 2021. -

October 2, 1896

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23. 1862—VOL. 34. FRIDAY OCTOBER . PORTLAND, MAINE. MORNING, 2, 1896j fS2Ki5£V8g!K| PRICE THREE CENTS. APSED. Many other were wrecked or THE REVIEWING STAND COLL buildings WOLCOTT AND CRANE. LATEST SIENTIFIC KNOWL- IS BECOMING SERIOUS. SIX MARYLAND VICTIMS. damaged. GAVE IT TO * REFORMS ASKED FOR. Three Men Drowned. GROVER. EDGE ON FOOD AND DIGESTION. Got. Drake of Iowa and Vice President The Gubernational Ticket Nominated by October 1.—During Tues- — ~ 1 he real cause ol most of our diseases Is Washington, » ■' ■ Massachusetts Republicans. Stevenson Badly Hurt. days storm the oyster schooner Capital simply an Inability to digest food. This induces \ foundered off Sandy Point, 35 miles thinness, loss of flesh and loss weakness, fat, down the Potomac. Three men were Boston, Ootober 1.—The annual state of vitality, wasting away. Canadian Pacific Burlington, Iowa. October 1.—Just From Tues- drowned. Trouble Assuming Further Loss Of Life Bryau Pays His to the convention of the Massachusetts Repub- Ladies of the W. C. T. U. Conven- Loss of flesh and vitality means constant after the in the semi-oenten- Respects procession licans for the nomination of a full state liability to sickness. Wasting away is con- Grave nial celebration got under headway and GENERAL STRIKE IMMINENT. Aspect. day’s Storm. President.. ticket and Presidential electors was con- tion Call for sumption. while were in the Many. 20,000 people streets, vened in Musio this at filf getting thin Is what tails you, there is only Bituminous Coil Miners Are Booking for hall, morning a reviewing stand broke down. -

North Coast Limited BRASS CAR SIDES

R O U T E O F T H E Vista-Dome North Coast Limited ek BRASS CAR SIDES Passenger Car Parts for the Streamliners HO North Coast Limited Budd Dining Cars (NP 459-463, CB&Q 458) #173-29 for Con-Cor Conversion, #173-89 for Walthers Conversion Six full dining cars were delivered by Budd in 1957-58 for the Vista-Dome North Coast Limited. They were the last full diners built before the advent of Amtrak. They displaced the Pullman-Standard dining cars NP 450-455 to service on the Mainstreeter. The Budd diners operated between Chicago and Seattle until the end of BN service in 1971. Dining cars were cycled in and out of eastbound No. 26 at St. Paul Union Depot and were serviced at the nearby NP Commissary. Five of the six cars were purchased by Amtrak in 1971 and operated in the North Coast Hiawatha, and later in the "Heritage Fleet", particularly on the trains between Chicago and New York and Washington. A typical summer consist for the North Coast Limited of the late 1950's and 1960's is listed below. [Side sets in brackets available from BRASS CAR SIDES or other manufacturers.] NP 400-411 Water-baggage (Chicago-Seattle) [173-56] NP 425-430 Mail-dorm (Chicago-Seattle) [173-50] NP 325-336 24-8 Budd Slumbercoach (Chicago-Seattle) [Walthers or Con-Cor] SP&S 559 46-Seat Vista-Dome coach (Chicago-Portland) [173-20] NP 588-599 56-Seat leg-rest coach (Chicago-Portland) [173-4] NP 549-556 46-Seat Vista-Dome coach (Chicago-Seattle) [173-20] NP 588-599 56-Seat leg-rest coach (Chicago-Seattle) [173-4] NP 500-517 56-Seat coach (extra cars as needed from -

Report on Streamline, Light-Weight, High-Speed Passenger Trains

T F 570 .c. 7 I ~38 t!of • 3 REPORT ON STREAMLINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT, HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRAINS June 30, 1938 • DEC COVE RDALE & COL PITTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS 120 WALL STREE:T, N ltW YORK REPORT ON STREAMLINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRAINS June 30. 1938 COVERDALE & COLPITTS " CONSUL..TING ENGINEERS 1a0 WALL STREET, NEW YORK INDEX PAOES J NTRODUC'r!ON • s-s PR£FATORY R£MARKS 9 uNION PAC! FIC . to-IJ Gen<ral statement City of Salina >ioRTH WESTERN-UNION PAcln c City of Portland City of Los Angd<S Cit)' of Denve'r NoRTH W£sTERN-l.:~<IOS P \ l"IIIC-Sm 1HrR" PACirJc . '9"'~1 Cit)' of San Francisco Forty Niner SouTHERN PAclnC. Sunbeam Darlight CHICAco, BuR~lNGTON & QuiN<'' General statement Origin:tl Zephyr Sam Houston Ourk State Mark Twain Twin Citi<S Zephyn Den\'tr Zephyrs CHICACO, ~ULWACK.EE, ST. l'AUL AND PACit' lt• Hiawatha CHICAOO AND NoRTH \Yss·rr;J<s . ,; -tOO" .•hCHISON, T orEKJ\ AND SAN'rA FE General statement Super Chief 1:.1 Capitan Son Diegon Chicagoan and Kansas Cityon Golden Gate 3 lJID£X- COIIIinutd PACES CmCAco, RocK IsLAND AND PACIFIC 46-50 General statement Chicago-Peoria Rocket Chicago-Des Moines Rocket Kansas City-Minneapolis Rocket Kansas City-Oklahoma City Rocket Fort Worth-Dallas-Houston Rocket lLuNOJS CENTRAL • Green Diamond GULF, MOBlL£ AI<D NORTHERN 53-55 Rebels New YoRK Cesr&AI•. Mercury Twentieth Century Limited, Commodore Vanderbilt PENNSYLVANiA . 57 Broadway Lirruted, Liberty Limited, General, Spirit of St. Louis BALTIMORE AND 0HJO • ss Royal Blue BALTIMORE AND OHIO-ALTO!\ • Abraham Lincoln Ann Rutledge READ!KC Crusader New YoRK, NEw HAvEN A~'l> HARTFORD Comet BosToN AND MAINE-MAt"£ CeNTRAL Flying Yankee CONCLUSION 68 REPORT ON STREA M LINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT, HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRA INS As of June 30, 1938 BY CovERDALE & COLPITTS INTRODUCTION N January 15, 1935, we made a the inauguration ofservice by the Zephyr O report on the performance of and a statement comparing the cost of the first Zephyr type, streamline, operation of the Zephyr with that of the stainless steel, light-weight, high-speed, trains it replaced. -

![1919-12-16 [P 15]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2615/1919-12-16-p-15-392615.webp)

1919-12-16 [P 15]

" boxing | mmm RIAN MEE'IS BILL} Windsor Five Here For The Melting Pot PAGER BIG HIE THOMPSON THURSDAY Return Tomorrow Sport News Boiled Down Game vs. Another card of fights has been ar- Colby Mick. will The following has been received But our man was game, if nothing ranged for Lhe Amboy Sporting Club The six round semi-final event who Colby of Chroma Fein DEFEAT from a fight fan of the fair sex. else on Thursday night, and the prog'im bring together young and KEPPGRT Tha basketball fans will thmong to around team work. Schelling seems to be quute a backer of the And still came up for more. will consist of one e ftht, one six nd and Henry Mick of I3rookIyn. Colby the Auditorium Court tomorrow night fast men a dead ot will be the forwards, two "iia.be Ruth of boxing" Al Roberta. three four round bouts. has been meeting with great to see the Windsor Big Five and the The Pacer Big Five of this city local w'ho have In wonderful “To AL” But he is only Just a kid Hyan vs. TIumipHon. success in the ring, having ap- team action for pttfortned traveled to last night, where local Auditorium in Keyport, h.m a to learn. the peared in preliminaries and scmL-flnal the local court already this There was a young fellow Let's give chance In the main event. Willie Hyan. the second time this season, the first style on they defeated the Aero Flyers of that all around box- His first naano was Al And u hen ho gets experience fc.st climbing vvel'er of New Bruns events. -

St. Benedict Option Taki: the Movie ANDREW BACEVICH Justin Raimondo ROD DREHER Taki

One Percent America Kennedy’s Wars St. Benedict Option Taki: The Movie ANDREW BACEVICH JUSTIN RAIMONDO ROD DREHER TAKI NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2013 IDEAS OVER IDEOLOGY • PRINCIPLES OVER PARTY WHY THE TEA PARTY CAN’T GOVERN by DANIEL MCCARTHY $9.99 US/Canada theamericanconservative.com “One of the best liberal arts colleges in America.” - George Weigel DISCOVER THE DIFFERENCE Catholic Liberal Arts at Its Best! Enter Our Full-Tuition SCHOLARSHIP Competition! Rigorous Liberal Arts Curriculum Integrated Core Emphasizing Research, Written & Oral Communication Scholarships and Robust Financial Aid Program Integrated Career Development Program Leadership and Internship Opportunities Semester in Rome and Summer Ireland Programs Intercollegiate Athletic Program Drama, Music, and Performance Opportunities Mission Trips and Outreach Programs Authentic Catholic Culture and Liturgical Celebrations Front Royal, Virginia 800.877.5456 Tomorrow’s Leaders. Here Today. christendom.edu Vol. 12, No. 6, November/December 2013 2224 3228 40 COVER STORY FRONT LINES ARTS & LETTERS 12 Why the Tea Party Can’t Govern 6 Mike Lee, rugged 40 Goliath: Life and Loathing Its conservatism is a product of communitarian in Greater Israel by Max the disco era. JONATHAN COPPAGE Blumenthal DANIEL MCCARTHY 7 The magazine for crunchy cons SCOTT MCCONNELL GRACY OLMSTEAD artIcles 44 Rebound: Getting America Back 9 Britain’s Tories need a woman. to Great by Kim R. Holmes 16 Benedict Option EMMA ELLIOTT FREIRE JUSTIN LOGAN The promise of Christian 46 Conservative Internationalism: intentional communities COMMentary ROD DREHER Armed Diplomacy Under Jefferson, Polk, Truman, and 5 Turning right since 2012 20 One Percent Republic Reagan by Henry Nau Inequality applies to military 11 Has the NSA gone too far? MICHAEL C. -

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/Notes Format Quantity

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/notes Format Quantity Sire Against Me! 2 song 7" single I Was A Teenage Anarchist (acoustic) 7" vinyl 2500 Sub-pop Album Leaf There Is a Wind Featuring 2 new tracks, 2 alternate takes 12" vinyl 1000 on songs from "A Chorus of Storytellers" LP Righteous Babe Ani DiFranco live @ Bull Moose recorded live on Record Store Day at CD Bull Moose in Maine Rough Trade Arthur Russell Calling Out of Context 12 new tracks Double 12" set 2000 Rocket Science Asteroids Galaxy Tour Fun Ltd edition vinyl of album with bonus 12" 250 track "Attack of the Ghost Riders" Hopeless Avenged Sevenfold Unholy Confessions picture disc includes tracks (Eternal 12" vinyl 2000 Rest, Eternal Rest (live), Unholy Confessions Artist First/Shangri- Band of Skulls Live at Fingerprints Live EP recorded at record store CD 2000 la 12/15/2009 Fingerprints Sub-pop Beach House Zebra 2 new tracks and 2 alternate from album 12" vinyl 1500 "Teen Dream" Beastie Boys white label 12" super surprise 12" vinyl 1000 Nonesuch Black Keys Tighten Up/Howlin' For 12" vinyl contains two new songs 45 RPM 12" Single 50000 You Vinyl Eagle Rock Black Label Society Skullage Double LP look at the history of Zakk Double LP 180 Wylde and Black Label Society Gram GREEN vinyl Graveface Black Moth Super Eating Us extremely limited foil pressed double LP double LP Rainbow Jagjaguwar Bon Iver/Peter Gabriel "Come Talk To Bon Iver and Peter Gabriel cover each 7" vinyl 2000 Me"/"Flume" other. Bon Iver track is EXCLUSIVE to this release Ninja Tune Bonobo featuring "Eyes -

Ing at Ounce

( .'i TUESDAY,''MAY 15, 1956 f a Qi ^ sccT Eo ir AYMRge Daily Net Preaa Run lianrlfeitfr lEurnitts 1|pfalb For «lM Week EiaSH May 12, 1888 ) The Weather ra n o H t t Vi n. Weather B « , Mechanical engineers from a lf , Andcraon-Shea Poat No.' 2048,' ter Health Dejiartment, of local ,094 A b o i l t T m m parts of Connecticut will celebrate VFW; will hold an important busl- Bradley Selected MarsHal / Vaccine Seeii phyaiciana who were, aakesl how the ■26th anniversary ef tlrtr 'ori m n meeting Uonight atjg;l6 at many patients In . the auHMrisM' MANCHESTER fthe Anilt nearlhg tM* avetdair. lair ganlaing of the American Society the poat home. All members afe a ge' bracket are awaiting ihqta. Baroaa W ClMalntteB eneler taalglit. IrMf 48-46. r k CaiMTlu T. >L « f 94 of Mechanical Engineers May 18 urged to attend. The meeting will For Memorial Day Par) Here by July Doctors art* allowed to give /Irat auto parts day M r. Hli8< iu middle die. WalKw at, »/ai1v*r ^ t h the at a Connecticut sections meeting be followed by a aoclaj hour and and second Shots to the i . i p 12 i Manchester—^ City of llUage Charm Hartford Urvf/nuil of tha^NaUonal at tha Rockledge Country Club In refreahmenti. year olds an)i to pregnant pothers. *70 BROAD BTREET The law forbids them to.inve thir(* Co. o f BkJdKcport West Hartford. Dr. Arthur B. Lvoh C. Bradley e f 73 Phelps •cWHIIam Knight, a Jun>6r, at Man-': Epr 1,900Tots VOL.