Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genpact Looks to a New Era Beyond “General Electric's Provider”

A Horses for Sources Rapid Insight Genpact Looks to a New Era beyond “General Electric’s Provider” Mike Atwood, Horses for Sources Phil Fersht, Horses for Sources In its first industry analyst conference, leading business process outsourcing (BPO) provider Genpact emphasized its business, today, is much broader than supporting General Electric’s back office and primarily delivering finance and accounting (F&A) services. The global service provider surpassed the $1 billion revenue threshold, in 2008 and new opportunities and challenges have emerged to scale and diversify its growing services business. “Tiger” Tyagarajan (Chief Operating Officer) and Bob Pryor (Executive Vice President, responsible for sales, marketing and new business development globally) co-hosted on May 18-19 in Cambridge, MA what Genpact billed as its first analyst and advisor conference. The event was well attended by all the analyst firms and many of the consulting firms which regularly help clients hire BPO firms such as Genpact. The largest of the advisory firms present was EquaTerra, which currently advises on the lion’s share of the BPO business. All and all, it was a good first effort, and more open than many service provider events we have attended in the past. The headline message was that the majority of Genpact’s business is no longer with its former parent GE (currently about 40 percent). In fact, its GE business actually declined last year as a percentage of total revenues. Further, only about one third of its business is now in finance and accounting outsourcing (FAO). As demand in other areas grows, Genpact will continue to verticalize its offerings in areas such as back office processing for financial institutions and healthcare companies, in addition to developing its IT services, and knowledge process outsourcing (KPO))/analytics offerings. -

PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE GG1 4800 National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark

PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE GG1 4800 National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark Friends of GG1 4800 The American Society of Mechanical Engineers Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania Strasburg, Pennsylvania April 23, 1983 he GG1 was a remarkable design, and so The locomotive required two frames; one of the two pantographs. Steps at the ends successful, because of its integrative each frame was a one-piece casting from the of the prototype GG1 led to the pantographs T synthesis of innovations from many General Steel Castings Corporation and was on the roof. But, as long as a pantograph was fields of engineering — mechanical, electrical, machined by Baldwin at Eddystone, Pennsyl- raised and “hot”, access was prevented by a industrial. vania. The two frames, each nearly forty feet blocking plate at the top of the steps. Throwing In 1913, before the era of the GG1, the long, held three driver axle assemblies and a a lever swung the plate clear but caused the Pennsylvania Railroad decided to electrify its two-axle pilot truck. Driver axles fit into roller pantograph to de-energize by dropping. tracks in the vicinity of Philadelphia. The bearing boxes that could move vertically in system, at 11,000 volts and 25 hertz, expanded pedestal jaws in the frame. The driver axle Three pairs of General Electric GEA-627-A1 until by the early 1930s it stretched from New was surrounded by a quill on which was electric motors were mounted in each frame. York City south to Wilmington, Delaware, and mounted a ring gear driven by the pinions of Each pair drove one quill. -

MTH DCS to DCC Conversion Changing Over an MTH Steam Loco As Detailed by Ray Grosser

Celebrating Scale the art of Trains 1:48 modeling MAGAZINE O u Sept/Oct 2008 Issue #40 US $6.95 • Can $8.95 Display until October 31, 2008 www.goldengatedepot.com / FAX: (408) 904-5849 GGD - RERUN P70s NEW CAR NUMBERS: ORDER IN PAIRS: PRR, PRSL, LIRR, $249.95 MSRP. RESERVE TODAY! VERY LIMITED QUANTITIES. RERUN PULLMAN 12-1 SLEEPERS IN ABS NEW CAR NAMES TOO: PRR, PULLMAN (GREEN), PULLMAN (TTG), ERIE (TWO TONE GREEN), LACKAWANNA (Grey and Maroon). RESERVE TODAY! COMING FALL 2008. $129.95 MSRP each. Set A: RPO/Baggage 5018 Diner 681 NYC 20th Century 1938 & 1940 4-4-2 Imperial Highlands YES WE ARE OFFERING THE 1940 STRIPING TOO! Observation Manhattan Is. Set B: Dorm/Club Century Club 17-Roomette City of Albany 10-5 Cascade Dawn 13-Double Bedroom Cuyahoga County Set C: Diner 682 17-Roomette City of Chicago Available in Late 2008 for $599.95 (RESERVE PRICE) per 4 Car Set 10-5 Cascade Glory 4-4-2 Imperial Falls 54’ STEEL REEFERS HW DINER / OBSERVATION Also: PRR - BIG CHANGE REA ORIG 4-2-1 PULLMAN OBSERVATION ACL D78br - DINER (w/3DP1 Trucks) GN B&O REA Green Pull-Green NYC SF OFFERED IN MANY OTHER ROADS WITH PULLMAN TRUCKS GGDGGD Aluminum Aluminum SetsSets -- PRICEPRICE CHANGE CHANGE - NYC ESE: 6 Car Set, 2 Car Add On ($599.95 / $299.95) FALL 2008 - Santa Fe 1937 Super Chief: 6 Car Set, 2 Car Add On ($599.95 / $299.95) FALL 2008 - Southern Pacific Daylight: 5 Car, 5 Articulated Add On ($599.95 / $599.95) Late 2008 - PRR Fleet of Mod. -

October 2, 1896

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23. 1862—VOL. 34. FRIDAY OCTOBER . PORTLAND, MAINE. MORNING, 2, 1896j fS2Ki5£V8g!K| PRICE THREE CENTS. APSED. Many other were wrecked or THE REVIEWING STAND COLL buildings WOLCOTT AND CRANE. LATEST SIENTIFIC KNOWL- IS BECOMING SERIOUS. SIX MARYLAND VICTIMS. damaged. GAVE IT TO * REFORMS ASKED FOR. Three Men Drowned. GROVER. EDGE ON FOOD AND DIGESTION. Got. Drake of Iowa and Vice President The Gubernational Ticket Nominated by October 1.—During Tues- — ~ 1 he real cause ol most of our diseases Is Washington, » ■' ■ Massachusetts Republicans. Stevenson Badly Hurt. days storm the oyster schooner Capital simply an Inability to digest food. This induces \ foundered off Sandy Point, 35 miles thinness, loss of flesh and loss weakness, fat, down the Potomac. Three men were Boston, Ootober 1.—The annual state of vitality, wasting away. Canadian Pacific Burlington, Iowa. October 1.—Just From Tues- drowned. Trouble Assuming Further Loss Of Life Bryau Pays His to the convention of the Massachusetts Repub- Ladies of the W. C. T. U. Conven- Loss of flesh and vitality means constant after the in the semi-oenten- Respects procession licans for the nomination of a full state liability to sickness. Wasting away is con- Grave nial celebration got under headway and GENERAL STRIKE IMMINENT. Aspect. day’s Storm. President.. ticket and Presidential electors was con- tion Call for sumption. while were in the Many. 20,000 people streets, vened in Musio this at filf getting thin Is what tails you, there is only Bituminous Coil Miners Are Booking for hall, morning a reviewing stand broke down. -

Baldwin Locomotive Works Location: Philadelphia (Eddystone, PA, in 1912) Operating Dates: 1831-1956 Principals: Matthias W

BUILDERS OF COLORADO OFFICE OF ARCHEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH COLORADO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Firm: Baldwin Locomotive Works Location: Philadelphia (Eddystone, PA, in 1912) Operating Dates: 1831-1956 Principals: Matthias W. Baldwin Information Jeweler and silversmith Matthias Baldwin founded the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1831. The original manufacturing plant was on Broad Street in Philadelphia where the company did business for 71 years until moving in 1912 to Eddystone, PA. Baldwin made its reputation building steam locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, and many of the other North American railroads, as well as for overseas railroads in England, France, India, Haiti and Egypt. Baldwin locomotives found their way onto the tracks of most Colorado railroads, both standard and narrow gauge. Baldwin built a huge number of 4-4-0 American type locomotives, but was perhaps best known for the 2-8-2 Mikado (D&RGW No. 491) and 2-8-0 Consolidation types (D&RGW No. 346 and DSP&P No. 191).1 It was also well known for the unique cab-forward 4-8-8-2 articulated locomotives built for the Southern Pacific Railroad and the massive 2-10-2 engines for the Santa Fe Railroad. One of Baldwin's last new and improved locomotive designs was the 4-8-4 (Northern) locomotive (Santa Fe No. 2911). In 1939, Baldwin offered its first standard line of diesel locomotives, all designed for rail yard service. Two years later, America's entry into World War II destroyed Baldwin's diesel development program when the War Production Board dictated that ALCO (American Locomotive Company) and Baldwin produce only diesel-electric yard switching engines. -

40Thanniv Ersary

Spring 2011 • $7 95 FSharing tihe exr periencste of Fastest railways past and present & rsary nive 40th An Things Were Not the Same after May 1, 1971 by George E. Kanary D-Day for Amtrak 5We certainly did not see Turboliners in regular service in Chicago before Amtrak. This train is In mid April, 1971, I was returning from headed for St. Louis in August 1977. —All photos by the author except as noted Seattle, Washington on my favorite train to the Pacific Northwest, the NORTH back into freight service or retire. The what I considered to be an inauspicious COAST LIMITED. For nearly 70 years, friendly stewardess-nurses would find other beginning to the new service. Even the the flagship train of the Northern Pacific employment. The locomotives and cars new name, AMTRAK, was a disappoint - RR, one of the oldest named trains in the would go into the AMTRAK fleet and be ment to me, since I preferred the classier country, had closely followed the route of dispersed country wide, some even winding sounding RAILPAX, which was eliminat - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, up running on the other side of the river on ed at nearly the last moment. and was definitely the super scenic way to the Milwaukee Road to the Twin Cities. In addition, wasn’t AMTRAK really Seattle and Portland. My first association That was only one example of the serv - being brought into existence to eliminate with the North Coast Limited dated to ices that would be lost with the advent of the passenger train in America? Didn’t 1948, when I took my first long distance AMTRAK on May 1, 1971. -

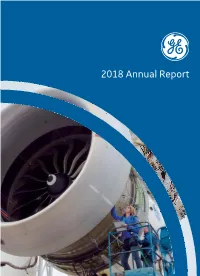

2018 Annual Report WHERE YOU CAN FIND MORE INFORMATION Annual Report

2018 Annual Report WHERE YOU CAN FIND MORE INFORMATION Annual Report https://www.ge.com/investor-relations/annual-report Sustainability Website https://www.ge.com/sustainability FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Some of the information we provide in this document is forward-looking and therefore could change over time to reflect changes in the environment in which GE competes. For details on the uncertainties that may cause our actual results to be materially different than those expressed in our forward-looking statements, see https://www.ge.com/ investor-relations/important-forward-looking-statement-information. We do not undertake to update our forward-looking statements. NON-GAAP FINANCIAL MEASURES We sometimes use information derived from consolidated financial data but not presented in our financial statements prepared in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Certain of these data are considered “non-GAAP financial measures” under the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rules. These non-GAAP financial measures supplement our GAAP disclosures and should not be considered an alternative to the GAAP measure. The reasons we use these non-GAAP financial measures and the reconciliations to their most directly comparable GAAP financial measures are included in the CEO letter supplemental information package posted to the investor relations section of our website at www.ge.com. Cover: The GE9X engine hanging on a test stand at our Peebles Test Operation facility in Ohio. Here we test how the engine’s high-pressure turbine nozzles and shrouds, composed of a new lightweight and ultra-strong material called ceramic matrix composites (CMCs), are resistant to the engine’s white-hot air. -

Download Our Latest White Paper, Lean Maintenance Programs: How Creative Machining Solutions Can Help, At

2005 MARCH COVER.qxd 3/2/2005 10:45 AM Page 1 March 2005 MARITIME REPORTER Cruise Shipbuilding AND ENGINEERING NEWS Italy Leads the Comeback www.marinelink.com Ship Safety SAFEDOR Launched Government Update Nontank Vessels Need Response Plans Investment in Design New Solutions for LNG Ships Navy X Marks the Spot New Products • Sea Technology • Tanker Market Report • Ships Store • SatCom Directory MR MARCH 2005 #1 (1-8).qxd 3/2/2005 11:58 AM Page 2 A Century of Navy Partnership Power Solutions When the Stakes are High More than a century ago, when the U.S. Navy wanted more precise targeting Call us to find out how our innovative and changed its aiming systems from hydraulic and steam-powered movement attitude can make you more successful to electric systems, Ward Leonard led the way, creating and installing the at 860-283-5801 world’s first multiple voltage system. The system played an important role in or visit us at www.wardleonard.com. the Spanish-American War. We’ve got answers. Today, as the U.S. Navy moves from hydraulic and mechanical systems to all electric, Ward Leonard is on station, innovating and partnering. We have just created an innovative, multi-protocol communications module that simplifies shipboard motor control management and reduces development costs while eliminating equipment duplications. Circle 288 on Reader Service Card MR MARCH 2005 #1 (1-8).qxd 2/28/2005 3:54 PM Page 3 ACCESS With C-MAP/Commercial’s CM-93 electronic chart database, you receive global coverage on one CD. Our 18,000+ electronic charts make navigating commercial vessels easier and safer than ever. -

Cruising the Information Highway: Online Services and Electronic Mail for Physicians and Families John G

Technology Review Cruising the Information Highway: Online Services and Electronic Mail for Physicians and Families John G. Faughnan, MD; David J. Doukas, MD; Mark H. Ebell, MD; and Gary N. Fox, MD Minneapolis, Minnesota; Ann Arbor and Detroit, Michigan; and Toledo, Ohio Commercial online service providers, bulletin board ser indirectly through America Online or directly through vices, and the Internet make up the rapidly expanding specialized access providers. Today’s online services are “information highway.” Physicians and their families destined to evolve into a National Information Infra can use these services for professional and personal com structure that will change the way we work and play. munication, for recreation and commerce, and to obtain Key words. Computers; education; information services; reference information and computer software. Com m er communication; online systems; Internet. cial providers include America Online, CompuServe, GEnie, and MCIMail. Internet access can be obtained ( JFam Pract 1994; 39:365-371) During past year, there has been a deluge of articles information), computer-based communications, and en about the “information highway.” Although they have tertainment. Visionaries imagine this collection becoming included a great deal of exaggeration, there are some the marketplace and the workplace of the nation. In this services of real interest to physicians and their families. article we focus on the latter interpretation of the infor This paper, which is based on the personal experience mation highway. of clinicians who have played and worked with com There are practical medical and nonmedical reasons puter communications for the past several years, pre to explore the online world. America Online (AOL) is one sents the services of current interest, indicates where of the services described in detail. -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Ray Marshall and Bob Hench: Back to School for Ge

RAY MARSHALL AND BOB HENCH: BACK TO SCHOOL FOR GE PaBe 7 PRODUCT LINE MANAGEMENT pwe~8-9 FIRST-QUARTER RESULTS PaBe 13 PC MAILBOX FOR GE CIT KESLE Ray Marshall, KESLE Bob Hench, KESLE Product Line Management Bottom Line GE First Quarter America's Cup Wrap-Up U.S. Electronic Privacy Act GE CIT Stock Split Approved ED1 Users' Group Good News Industry Briefs Documentation Happy Birthday, Mr. Edison S&SP Milestones Contributors SPECTRUM is published for employees by Employee Communication, GE Information Services, 401 N. Washington St. OlD, Rockuille, Maryland 20850, U.S.A. For distribution changes, send a message via the QUIK-COMMTU System to OLOS. For additional copies, send a QUIK-COMM message to OLOS, publication number 0308.22. SPECTRUM Editor: Sallie Birket Chafer Managing Editor: Spencer Carter QUIK-COMM: SALLIE; DIAL COMM: B"273- 4476 INFORMATION SERVICES RAY MARSHALL AND BOB HENCH: BACK TO SCHOOL FOR GE This [robot arm equipment for the Engineering Ray Marshall (Technology Operations) and Bob Department] is another indication of thegrowing Hench (Information Processing Technology) have relationship between higher education and the private been spending a lot of time in school lately. For the sector. Both GE and Michigan State University have past four and six years, respectively, they have joined long been regarded as leaders in this type of key operating managers in other GE components who relationship. What this does is continue to reinforce serve in the Corporate-sponsored Key Engineering the linkage between this university, industry, and School Liaison Executive (KESLE) program. government. Our destinies are intertwined. -

Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems

MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THESIS N° 2568 (2002) PRESENTED AT THE CIVIL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY - LAUSANNE BY GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Civil Engineer, EPFL French nationality Approved by the proposition of the jury: Prof. F.L. Perret, thesis director Prof. M. Hirt, jury director Prof. D. Foray Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps Prof. M. Finger Prof. M. Bassand Lausanne, EPFL 2002 MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THÈSE N° 2568 (2002) PRÉSENTÉE AU DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉNIE CIVIL ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE PAR GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Ingénieur Génie-Civil diplômé EPFL de nationalité française acceptée sur proposition du jury : Prof. F.L. Perret, directeur de thèse Prof. M. Hirt, rapporteur Prof. D. Foray, corapporteur Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps, corapporteur Prof. M. Finger, corapporteur Prof. M. Bassand, corapporteur Document approuvé lors de l’examen oral le 19.04.2002 Abstract 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Prof. Francis-Luc Perret, my Supervisory Committee Chairman, as well as to Prof. Dominique Foray for their enthusiasm, encouragements and guidance. I also express my gratitude to the members of my Committee, Prof. Jean-Philippe Deschamps, Prof. Mathias Finger, Prof. Michel Bassand and Prof. Manfred Hirt for their comments and remarks. They have contributed to making this multidisciplinary approach more pertinent. I would also like to extend my gratitude to our Research Institute, the LEM, the support of which has been very helpful. Concerning the exchange program at ITS -Berkeley (2000-2001), I would like to acknowledge the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation.