Responsibility and Accountability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in Hato Builico Timor Leste

Blue Mountains East Timor Friendship Committee The Friendship Committee was formed in 2006 as part of an Australia-wide initiative to develop friendship agreements with communities in Timor-Leste. To date, more than 40 councils across Australia have participated. Walking in Hato Builico The Blue Mountains committee is made up of community members, councillors and council staff from Blue Mountains City Council, all committed to improving the lives of the rural community of Hato Builico. A partner committee of residents of Hato Timor Leste Builico assesses the needs of the community and liaises with the Blue Mountains to progress projects. Fundraising events are organised regularly by volunteers. If you live in or plan to visit Australia in 2012, what about raising funds for Hato Builico by joining the sponsored Trek for Timor Blue Mountains on September 15th 2012. 50km or 15km - the choice is yours. www.trekfortimorbm.org.au Members of the Blue Mountains committee visit regularly on self-funded trips to monitor progress of projects and to talk to villagers about their needs. In 2011, a volunteer from Australian Volunteers International will spend extended periods in Hato Builico to work on local projects. Projects so far have included: Refurbishment of a community centre for training and community meetings Scholarships for 43 students to attend primary school, high school and university Collaborations between schools in East Timor and Blue Mountains Hedge seedlings to counteract the effects of deforestation Solar panels for the community centre Two water tanks for the community centre (supported by Rotary) Sports equipment, school equipment, readers and guitars for schools as well as participation in training for sports teaching And of course – this project! Two volunteers from the Blue Mountains spent three months living in Hato Builico and developing this series of guided walks. -

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3216 INTERNATIONAL

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3216 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 42.5 MILLION (US$59.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF TIMOR-LESTE FOR A TIMOR-LESTE BRANCH ROADS PROJECT November 1, 2019 Transport Global Practice East Asia And Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 30, 2019) Currency Unit = United States Dollar (US$) SDR 0.71932 = US$1 US$1.39021 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Country Director: Rodrigo A. Chaves Regional Director: Ranjit Lamech Practice Manager: Almud Weitz Task Team Leader(s): Rodrigo Archondo-Callao, Elena Y. Chesheva ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic ADB Asian Development Bank ADN Agência de Desenvolvimento Nacional (National Development Agency) CAFI Conselho de Administração do Fundo Infraestrutura (Council for the Administration of the Infrastructure Fund) CERC Contingent Emergency Response Component CESMP Contractor’s Environmental and Social Management Plan CO2 Carbon Dioxide DA Designated Account DED Detailed Engineering Design DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade DG Director General DRBFC Directorate of Roads, Bridges and Flood Control EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environmental Management Plan -

World Bank Document

INTEGRATED SAFEGUARDS DATASHEET APPRAISAL STAGE I. Basic Information Date prepared/updated: 09/11/2012 Report No.: AC6721 Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Basic Project Data Original Project ID: P125032 Original Project Name: Timor Leste Road Climate Resilience Project Country: Timor-Leste Project ID: P130975 Project Name: Timor Leste Road Climate Resilience Project - Additional Financing Task Team Leader: Mitsuyoshi Asada Estimated Appraisal Date: April 30, 2012 Estimated Board Date: March 21, 2013 Managing Unit: EASNS Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Sector: Rural and Inter-Urban Roads and Highways (85%);Public administration- Transportation (15%) Theme: Climate change (60%);Rural services and infrastructure (20%);Regional Public Disclosure Authorized integration (20%) IBRD Amount (US$m.): 30 IDA Amount (US$m.): 10 GEF Amount (US$m.): 0 PCF Amount (US$m.): 0 Other financing amounts by source: Borrower 52.00 52.00 Environmental Category: B - Partial Assessment Simplified Processing Simple [] Repeater [] Is this project processed under OP 8.50 (Emergency Recovery) Public Disclosure Authorized Yes [ ] No [X] or OP 8.00 (Rapid Response to Crises and Emergencies) 2. Project Objectives The project will deliver sustainable climate resilient road infrastructure on the Dili- Ainaro corridor. 3. Project Description The project would provide additional financing for the ongoing Timor Leste Road Climate resilience Project (TLRCRP). The proposed Additional Financing will finance the following revised components under RCRP: Component A: Climate Resilient Road Infrastructure This component will invest in key road infrastructure to improve its climate resilience. Public Disclosure Authorized The objective is to reduce the impact of the increasing traffic volume and intensity of rainfall on the road corridor from Dili to Ainaro. -

Project Brief: Enhancing Rural Access

Project Brief International Labour Organization Enhancing Rural Access (ERA) Objective To improve access and income opportunities for rural communities through rehabilitation and maintenance of rural roads by trained contractors. Key Partners Secretariat of State for Support and Promotion of Private Sector (SEAPRI) Ministry of Public Works (MPW) Don Bosco Foundation, Training Center in Comoro Instituto de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Empresarial (IADE) Chambers of Commerce and Industry Timor-Leste (CCI-TL) Duration 4 years (2011 – 2015) Geographical Timor-Leste, Districts of Ainaro, Aileu, Bobonaro, Covalima, Ermera and Liquica Coverage Country Programme Enhanced rural employment, safety net, and economy through infrastructure investment Reference and private sector development. Donor The European Union Budget EUR 10,000,000 Contact Tomas Stenstrom | Project Chief Engineer | [email protected] Donato da Costa Pinheiro | Don Bosco Training Coordinator | [email protected] Project Background Timor-Leste is one of the least developed countries capacities, both in the private sector, in contract in the region. Its economy is essentially agriculture- management and in training delivery. Whilst the main based, with approximately 75% of its total population of objective of ERA is improved access through the about 1.1 million living in rural areas. A key constraint rehabilitation and maintenance of rural roads, this will to economic development is the poor condition of largely be done by local contractors trained in using a infrastructure in general, and the road network in labour-based approach. particular. Another serious structural problem of the economy is the inability to create employment Labour-based technology (LBT) optimizes the use of opportunities for the rapidly expanding labour force. -

3. Promotion of Community Reconciliation and Peacebuilding Process Through Development Projects

3. Promotion of Community Reconciliation and Peacebuilding Process through Development Projects War-affected communities possess particular mutual characteristics. The evaluation report on post-conflict humanitarian assistance prepared by UNDP and the Japanese government (2002) concludes that many features in post-conflict situations affect all humanitarian assistance projects: Lack of baseline data and lack of reliable information relating to damages and needs of the communities lead the requirement of modification in planning and budgeting of projects. Security issues and the difficulties of arranging logistics delay the projects. The presence of international organisations and personnel raises the prices of every product dramatically in the country and makes for an unnatural economy. This also increases the project budget. Short term contract of staff in international organisations in war-affected countries makes cooperation among humanitarian assistance organisations, as well as the sustainability of projects, difficult physically. In many cases, the recipient government and its administration system are not existing or not viable enough. And there are lack of techniques and the people who have special skills and techniques. This increases the dependency of the recipient countries on international assistance. This chapter will discuss how the development project could or should promote the community reconciliation and peacebuilding process at the community level. Firstly, the author will describe the development projects in Ainaro district. Secondly, the author will assess three particular development projects; aim, performance, implementation structure, relationship with local communities, relevance, efficiency, effectiveness, impact, sustainability, challenges and relation with promoting reconciliation process. Then discuss how the development project could or should promote the community reconciliation and peacebuilding process at the community level based on the lessons learned from project analysis in Ainaro. -

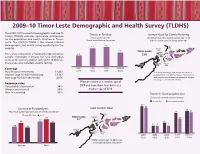

Timor-Leste DHS 2009-10 Fact Sheet

2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey (TLDHS) The 2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Trends in Fertility Unmet Need for Family Planning Survey (TLDHS) provides up-to-date information TFR for women for the Percent of currently married women age 15-49 on the population and health situation in Timor- 3-year period before the survey with an unmet need for family planning* Leste. The 2009–10 TLDHS is the second national demographic and health survey conducted in the 7.4 7.8 Dili 29% country. Liquiçá Lautem 5.7 Timor-Leste 29% Baucau 28% Aileu Manatuto 35% 27% The survey is based on a nationally representative 4.4 31% Ermera 30% Viqueque sample. It provides estimates for rural and urban 23% 31% Bobonaro Manufahi areas of the country and for each of the 13 districts. 42% 22% The survey also included anemia testing. Oecussi Covalima Ainaro 40% 17% 43% Coverage 1997 2002 2003 2009-10 IDHS MICS DHS TLDHS Households interviewed 11,463 *Currently married fecund women who want to Women (age 15–49) interviewed 13,137 postpone their next birth for two or more years or Men (age 15–54) interviewed 4,076 who want to stop childbearing altogether but are not using a contraceptive method Women marry at a median age of Response rates Households interviewed 98% 20.9 and have their first birth at a Women interviewed 95% median age of 22.4. Men interviewed 92% Trends in Contraceptive Use Percent of currently married women Any method Any modern method 27 25 Literacy of Respondents Total Fertility Rate 22 21 Percent of women and men age 15-49 -

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’S Office (RCO) Situation Report No

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) Situation Report No. 6 (As of 21 April 2021) This report is produced by RCO Timor-Leste in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by UN Timor-Leste. It covers the period from 16 to 21 April 2021. The next report will be issued on or around 28 April 2021. HIGHLIGHTS • Following the Government’s declaration of a state of calamity in Dili on 8 April, several humanitarian donors have provided additional humanitarian support the flood response, equivalent to nearly USD 10 million. • According to the latest official figures (21 April) from the Ministry of State Administration, which leads the Task Force for Civil Protection and Natural Disaster Management, a total of 28,734 households have reportedly been affected by the floods across all 13 municipalities. Of whom, 90% - or 25,881 households – are in Dili municipality. • The same report cites that currently there are 6,029 temporary displaced persons in 30 evacuation facilities across Dili, the worst-affected municipality. • 4,546 houses across all municipalities have reportedly been destroyed or damaged. • According to the preliminary assessment by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries conducted in 9 municipalities to date, a total of 1,820 ha of rice crops and 190 ha of maize crops have been affected by the flooding. 13 28,734 4,546 30 41 Municipalities Total affected Houses Evacuation Fatalities affected (out households destroyed or facilities in of 13 across the damaged across Dili municipalities) country the country SITUATION OVERVIEW Heavy rains across the country from 29 March to 4 April have resulted in flash floods and landslides affecting all 13 municipalities in Timor-Leste to varying degrees, with the capital Dili and the surrounding low-lying areas the worst affected. -

The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EAST TIMOR TRANSITIONAL ADMINISTRATION THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT VolumeⅠ: SUMMARY REPORT FEBRUARY 2001 TOKYO ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, CO., LTD. PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL SSS JR 01-040 THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT CONSTITUENT VOLUMES VOLUME Ⅰ SUMMARY REPORT VOLUME Ⅱ MAIN REPORT VOLUME Ⅲ APPENDIX VOLUME Ⅳ QUICK PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL Foreign Exchange Rate: USD 1.00 = INDONESIA RUPIAH 9,500 AUD 1.00 = JPY 58.50 USD 1.00 = JPY 111.07 (Status as of the 30 November 2000) PREFACE In response to a request from the United Nations Transitional Administration of East Timor, the Government of Japan decided to conduct The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Kazufumi Momose of Tokyo Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. in association with Pacific Consultants International to East Timor, twice between February 2000 and February 2001. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration and Asian Development Bank which is a trustee of East Timor Trust Fund and conducted field surveys in the study area. Based on the field surveys, the Study Team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between Japan and East Timor Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration for their close cooperation extended to the Study. -

Analytical Report on Education Timor-Leste Population and Housing Census 2015

Census 2015 Analytical Report on Education Timor-Leste Population and Housing Census 2015 Thematic Report Volume 11 Education Monograph 2017 Copyright © GDS, UNICEF and UNFPA 2017 Copyright © Photos: Bernardino Soares General Directorate of Statistics (GDS) United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 1 Executive Summary Education matters. It is the way through which one generation passes on its knowledge, experience and cultural legacy to the next generation. Education has the means to empower individuals and impacts every aspect of life. It is the vehicle to how one develops and understands the world. It creates opportunities for decent work and higher income and is correlated to many other components which can enrich one's quality of life and contribute to happiness, health, mental well-being, civic engagement, home ownership and long-term financial stability. Besides the economic implications, education is a fundamental right of each and every child. It is a matter of fulfilling basic human dignity, believing in the potential of every person and enhancing it with knowledge, learning and skills to construct the cornerstones of healthy human development (Education Matters, 2014)1. It is important to consider those most vulnerable and deprived of learning and ensure they receive the access to education they deserve. Simply stated: all children form an integral part of a country's future and therefore all should be educated. To protect the right of every child to an education, it is crucial to focus on the following components2: a) early learning in pre-schools, b) equal access to education for all children, c) guarantee education for children in conflict or disaster-prone areas and emergencies, d) enhance the quality of the schools, e) create partnerships to ensure funding and support and f) Build a strong education system. -

Democratic Republic of Timor Leste Country Profile for Emergencies and Disasters

Democratic Republic of Timor Leste Country Profile for Emergencies and Disasters Context The Democratic Republic of Timor Leste is located in the eastern part of the Timor Island with the western part belonging to the Republic of Indonesia as part of the East Nusa Tengara province. It is bordered by the Wetar straits to the north and the Timor Sea in the South. From the 1511 till 1975 Timor Leste was a colony of Portugal. This was followed by the Indonesian annexation in which the Timorese continued to fight for independence through the guerilla resistance movement. It was a period wrought with violence, human rights abuses and an estimated 200,000 deaths. In 30 August 1999 the East Timorese voted in an historic referendum for independence. In May 20, 2002 after two years of an interim UN Transitional Administration, the country gained its independence. Currently there are still 30,000 East Timorese nationals in West Timor, most of whom have no intentions of returning to the new republic of Timor Leste. An Indonesian Government program is currently working in the resettlement of these East Timorese to Sumba island. Some violent incidents perpetrated At present Timor Leste, with a population of 850,000 ranks as one of the 10 poorest countries in the world. It has a GDP per capita of US$ 478 with 41% of the population living below the poverty line of US$ 0.55 a day. 1 2 The Government is still in its infancy stages however much progress has been made in the rehabilitation of many institutions particularly in education and health- the two priorities of the National Development Plan. -

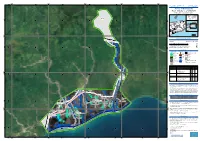

AINARO, V1 Ainaro - TIMOR-LESTE Flood - Situation As of 07/04/2021 Delineation - Overview Map 01

750000 760000 770000 780000 790000 125°16'0"E 125°20'0"E 125°24'0"E 125°28'0"E 125°32'0"E 125°36'0"E GLIDE number: FF-2021-000032-TMP Activation ID: EMSR507 Int. Charter Act. ID: 701 Product N.: 03AINARO, v1 Ainaro - TIMOR-LESTE Flood - Situation as of 07/04/2021 Delineation - Overview map 01 Banda Sea S Ainaro! " 0 ' 0 ° S " 9 0 ' 0 ° 9 Banda Sea Lautem 01 Dili 02 Baucau Manatuto Liquica Aileu Dil^i ViqSauvue Sqeaue Timor-Leste Ermera Bobonaro Ainaro !( Indonesia Timor Sea 04 Manufahi Ainaro 03 Timor Sea Cova Lima 25 0 0 0 0 km 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 9 Cartographic Information Plan etSco pe (07 /04/20 21 at 1:65000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution 01:34 UTC) 0 1.25 2.5 5 km S " Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 51S map coordinate system 0 ' 4 ° S " 9 Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system 0 ' 4 ° ± 9 Legend Crisis Information Placenames Facilities Flooded Area ! Placename Construction for mining or extraction (07/04/2021 01:34 UTC) Flood trace Built-Up Area Transportation General Information Built-Up Area Highway Area of Interest Hydrography Primary Road Coastline Image Footprint Local Road River Not Analysed Cart Track Stream Not Analysed - No data Physiography & Land Use - Land Cover ! Administrative boundaries River Features available in the vector package Region Province Consequences within the AOI Unit of measurement Affected Total in AOI Flood trace ha 520.4 Flooded area ha 39.4 Estimated population Number of inhabitants 318 19 976 Built-up Residential Buildings ha 10.5 909.6 Office buildings ha 0.0 0.7 Industrial buildings ha 0.0 -

Timor-Leste Strategic Development Plan, 2011–2030

SDP 2011-2013 PART 1: INTRODUCTION SDP 2011-2013 PART 1: INTRODUCTION TIMOR-LESTE STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011 - 2030 VERSION SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL PARLIAMENT 1 SDP 2011-2013 PART 1: INTRODUCTION 2 SDP 2011-2013 TIMOR-LESTESDP 2011-2013 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011 - 2030 PART 1: INTRODUCTION PART 1: INTRODUCTION CONTENTS PART 1 INTRODUCTION 7 OVERVIEW 8 BACKGROUND 9 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 11 PART 2 SOCIAL CAPITAL 13 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 14 HEALTH 33 SOCIAL INCLUSION 44 ENVIRONMENT 53 CULTURE AND HERITAGE 61 PART 3 INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 69 ROADS AND BRIDGES 70 WATER AND SANITATION 77 ELECTRICITY 85 SEA PORTS 93 AIRPORTS 97 TELECOMMUNICATIONS 99 PART 4 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 105 RURAL DEVELOPMENT 107 AGRICULTURE 118 PETROLEUM 136 TOURISM 141 PRIVATE SECTOR INVESTMENT 151 PART 5 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 157 SECURITY 158 DEFENCE 163 FOREIGN AFFAIRS 170 JUSTICE 176 PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGEMENT AND GOOD GOVERNANCE 181 NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY AND ECONOMIC POLICY AND INVESTMENT AGENCY 188 PART 6 ECONOMIC CONTEXT AND MACROECONOMIC DIRECTION 192 PART 7 CONCLUSION AND STAGING OF THE STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 215 3 TIMOR-LESTESDP 2011-2013 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011 - 2030 PART 1: INTRODUCTION DISTRICT MAP OF TIMOR-LESTE 2011 Source: UNDP 4 SDP 2011-2013 TIMOR-LESTESDP 2011-2013 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011 - 2030 PART 1: INTRODUCTION PART 1: INTRODUCTION LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1 – ESTIMATED SCHOOL INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS 15 TABLE 2 – PROGRESS ACHIEVED IN BASIC EDUCATION, 2000 TO 2010 17 TABLE 3 – SECONDARY EDUCATION IN TIMOR-LESTE, 2010 20 TABLE 4 – GRADUATED STUDENTS (CUMULATIVE DATA UP TO 2011) 22 TABLE 5 – SUMMARY OF EXISTING HEALTH FACILITIES IN TIMOR-LESTE 34 TABLE 6 – BENEFITS PAID UNDER DECREE-LAW NO.