International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbon Sequestration Potential of Oil Palm Plantations in Southern Philippines

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.14.041822; this version posted April 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Oil Palm Plantations in Southern Philippines ∗ Sheila Mae C. Borbon, Michael Arieh P. Medina , Jose Hermis P. Patricio, and Angela Grace Toledo-Bruno Department of Environmental Science, College of Forestry and Environmental Science Central Mindanao University, University Town, Musuan, Bukidnon, Philippines Abstract. Aside from the greenhouse gas reduction ability of palm oil-based biofuel as alternative to fossil fuels, another essential greenhouse gas mitigation ability of oil palm plantation is in terms of offsetting anthropogenic carbon emissions through carbon sequestration. In this context, this study was done to determine the carbon sequestration potential of oil palm plantations specifically in two areas in Mindanao, Philippines. Allometric equation was used in calculating the biomass of oil palm trunk. Furthermore, destructive methods were used to determine the biomass in other oil palm parts (fronds, leaves, and fruits). Carbon stocks from the other carbon pools in the oil palm plantations were measured which includes understory, litterfall, and soil. Results revealed that the average carbon stock in the oil palm plantations is 40.33 tC/ha. Majority of the carbon stock is found in the oil palm plant (53%), followed by soil (38%), litterfall (6%), and understory, (4%). The average carbon sequestration rate of oil palm plants is estimated to be 4.55 tC/ha/year. -

Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Ecosystems General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 6 Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L. 2008. Wildland fire in ecosystems: fire and nonnative invasive plants. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 6. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 355 p. Abstract—This state-of-knowledge review of information on relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants can assist fire managers and other land managers concerned with prevention, detection, and eradi- cation or control of nonnative invasive plants. The 16 chapters in this volume synthesize ecological and botanical principles regarding relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants, identify the nonnative invasive species currently of greatest concern in major bioregions of the United States, and describe emerging fire-invasive issues in each bioregion and throughout the nation. This volume can help increase understanding of plant invasions and fire and can be used in fire management and ecosystem-based management planning. The volume’s first part summarizes fundamental concepts regarding fire effects on invasions by nonnative plants, effects of plant invasions on fuels and fire regimes, and use of fire to control plant invasions. The second part identifies the nonnative invasive species of greatest concern and synthesizes information on the three topics covered in part one for nonnative inva- sives in seven major bioregions of the United States: Northeast, Southeast, Central, Interior West, Southwest Coastal, Northwest Coastal (including Alaska), and Hawaiian Islands. -

Revised Guidelines

Contents S. No. Description Page 1. Background 3 2. Review of the earlier NBM and Issues to be addressed 3 3. Objectives 6 4. Strategy 7 5. Key Outputs 8 6. Mission Structure 9 I) National Level 9 Executive Committee 9 Sub Committee 1 10 Sub Committee 2 10 National Bamboo Mission Cell 11 Bamboo Technical Support Group 11 II) State Level 12 State Level Executive Committee 12 State Bamboo Mission 13 III) District Level 14 7. Preparation of Action Plan and Approvals 15 8. Monitoring & Evaluation 15 9. Funding Pattern 16 10. Mission Intervention 16 10.1 Research & Development 17 10.2 Plantation development 18 10.2.1 Establishment of Nurseries 19 10.2.2 Certified Planting Material 19 10.2.3 Nurseries 19 10. 2.4 Raising New Plantations 20 10. 3 Extension, Education and Skill Development 20 10. 4 Micro-Irrigation 21 10.5 Post-harvest storage and treatment facilities 21 10.6 Promotion and Development of Infrastructure for Bamboo 22 Market 10. 7 Bamboo Market Research 22 10.8 . Incubation Centres 23 Page 1 of 40 10.9 . Production, Development & Processing 23 10.10 Role of Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) & Other Agencies for 23 Capacity Building 10.11 Export of Bamboo Based Products 23 Annexure I: State wise list of infrastructure created in earlier NBM Annexure II: Intervention for implementation role of Ministries/ Departments Annexure III: Indicative BTSG Component Annexure IV: Interventions with cost norms and funding pattern Annexure V: Format for submission of Annual Action Plan Annexure VI: Format for application for the approval of Executive Committee Page 2 of 40 OPERATIONAL GUIDELINES OF RESTRUCTURED NATIONAL BAMBOO MISSION 1. -

Book of Abstracts.Pdf

1 List of presenters A A., Hudson 329 Anil Kumar, Nadesa 189 Panicker A., Kingman 329 Arnautova, Elena 150 Abeli, Thomas 168 Aronson, James 197, 326 Abu Taleb, Tariq 215 ARSLA N, Kadir 363 351Abunnasr, 288 Arvanitis, Pantelis 114 Yaser Agnello, Gaia 268 Aspetakis, Ioannis 114 Aguilar, Rudy 105 Astafieff, Katia 80, 207 Ait Babahmad, 351 Avancini, Ricardo 320 Rachid Al Issaey , 235 Awas, Tesfaye 354, 176 Ghudaina Albrecht , Matthew 326 Ay, Nurhan 78 Allan, Eric 222 Aydınkal, Rasim 31 Murat Allenstein, Pamela 38 Ayenew, Ashenafi 337 Amat De León 233 Azevedo, Carine 204 Arce, Elena An, Miao 286 B B., Von Arx 365 Bétrisey, Sébastien 113 Bang, Miin 160 Birkinshaw, Chris 326 Barblishvili, Tinatin 336 Bizard, Léa 168 Barham, Ellie 179 Bjureke, Kristina 186 Barker, Katharine 220 Blackmore, 325 Stephen Barreiro, Graciela 287 Blanchflower, Paul 94 Barreiro, Graciela 139 Boillat, Cyril 119, 279 Barteau, Benjamin 131 Bonnet, François 67 Bar-Yoseph, Adi 230 Boom, Brian 262, 141 Bauters, Kenneth 118 Boratyński, Adam 113 Bavcon, Jože 111, 110 Bouman, Roderick 15 Beck, Sarah 217 Bouteleau, Serge 287, 139 Beech, Emily 128 Bray, Laurent 350 Beech, Emily 135 Breman, Elinor 168, 170, 280 Bellefroid, Elke 166, 118, 165 Brockington, 342 Samuel Bellet Serrano, 233, 259 Brockington, 341 María Samuel Berg, Christian 168 Burkart, Michael 81 6th Global Botanic Gardens Congress, 26-30 June 2017, Geneva, Switzerland 2 C C., Sousa 329 Chen, Xiaoya 261 Cable, Stuart 312 Cheng, Hyo Cheng 160 Cabral-Oliveira, 204 Cho, YC 49 Joana Callicrate, Taylor 105 Choi, Go Eun 202 Calonje, Michael 105 Christe, Camille 113 Cao, Zhikun 270 Clark, John 105, 251 Carta, Angelino 170 Coddington, 220 Carta Jonathan Caruso, Emily 351 Cole, Chris 24 Casimiro, Pedro 244 Cook, Alexandra 212 Casino, Ana 276, 277, 318 Coombes, Allen 147 Castro, Sílvia 204 Corlett, Richard 86 Catoni, Rosangela 335 Corona Callejas , 274 Norma Edith Cavender, Nicole 84, 139 Correia, Filipe 204 Ceron Carpio , 274 Costa, João 244 Amparo B. -

Solid Bamboo Installation Instructions

Installation Instructions Pre-Finished Solid Bamboo Portfolio Naturals | Synergy MPL | Signature Naturals | Craftsman II | Wright Bamboo Industry Designation of Solid 4. Bamboo flooring installation should be one of the last items completed on the construction project. Limit Bamboo: foot traffic on the finished bamboo floor. The customary construction of solid bamboo traditionally describes Grading Standards 1. Flat - Three layers of bamboo strips laminated edge General Rules: to edge on top of one another. In solid flat grain, Bamboo flooring shall be tongue and grooved and end the grain of the bamboo layers all run in the same matched, unless otherwise indicated, as Välinge Self direction. Locking. Flooring shall not be considered of standard grade unless properly dried. The drying standard for 2. Vertical - Multiple layers of bamboo strips laminated Teragren Bamboo solid bamboo product shall be 7 to top to bottom and laid on their sides. Exposing the 9% moisture content by volume with a plus or minus narrow edge of the bamboo strip to the surface of the factor of 2% for storage conditions in various climate plank. zones. 3. Strand Woven Bamboo - Multiple layers woven Grading Rules: together, and all running in same direction from top to Teragren Bamboo floors are not graded in the same bottom of plank, therefore the behavior of this type of way as hardwood flooring. Bamboo has many construction most closely resembles the properties of similarities to wood but different grading standards are solid hardwood – thus the designation. applied. The main stem of a bamboo is called a culm. The Attention culm is the support structure for the branches and leaves, and contains the main vascular system for the Before starting installation, read all instructions transport of water, nutrients and food. -

Physical, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2004 Physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of bamboo and its utilization potential for fiberboard manufacturing Xiaobo Li Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Li, Xiaobo, "Physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of bamboo and its utilization potential for fiberboard manufacturing" (2004). LSU Master's Theses. 866. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/866 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL, AND MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF BAMBOO AND ITS UTILIZATION POTENTIAL FOR FIBERBOARD MANUFACTURING A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faulty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In The School of Renewable Natural Resources By Xiaobo Li B.S. Beijing Forestry University, 1999 M.S. Chinese Academy of Forestry, 2002 May, 2004 Acknowledgements The author would like to express his deep appreciation to Dr. Todd F. Shupe for his guidance and assistance throughout the course of this study. He will always be grateful to Dr. Shupe’s scientific advice, detailed assistance, and kind encouragement. The author would always like to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Chung Y. -

Dear Readers Welcome to the 30Th Issue of Produce Vegetable Oil

Dear readers Welcome to the 30th issue of produce vegetable oil. The oil is not We continue to feature APANews! This issue includes several only rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and developments in agroforestry interesting articles on recent potassium, but can also be education and training through the developments in agroforestry. We converted into industrial biodiesel. SEANAFE News. Articles in this issue also have several contributions This article is indeed timely as recent of SEANAFE News discuss about presenting findings of agroforestry research efforts are focusing on projects on landscape agroforestry, research. alternative sources of fuel and and marketing of agroforestry tree energy. products. There are also updates on Two articles discuss non-wood forest its Research Fellowship Program and products in this issue. One article Another article presents the results reports from the national networks of features the findings of a research of a study that investigated the SEANAFE’s member countries. that explored various ways of storing physiological processes of rattan seeds to increase its viability. agroforestry systems in India. The There are also information on The article also presents a study focused on photosynthesis and upcoming international conferences comprehensive overview of rattan other related growth parameters in agroforestry which you may be seed storage and propagation in that affect crop production under interested in attending. Websites Southeast Asia. tree canopies. and new information sources are also featured to help you in your Another article discusses the In agroforestry promotion and various agroforestry activities. potential of integrating Burma development, the impacts of a five- bamboo in various farming systems year grassroots-oriented project on Thank you very much to all the in India. -

Bamboo Cultivation RASHTRIYA KRISHI Volume 10 Issue 1 June, 2015 47-49 E ISSN–2321–7987 | Article |Visit Us

Bamboo Cultivation RASHTRIYA KRISHI Volume 10 Issue 1 June, 2015 47-49 e ISSN–2321–7987 | Article |Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in| Bamboo cultivation : Generating income for the rural poor Hiralal Jana Department of Agricultural Extension, College of Agriculture, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, BURDWAN (W.B.) INDIA (Email: [email protected]) Diminishing resources and availability of forest wood Madhya Pradesh, 9.90 per cent in Maharashtra, 8.7 per and conservation concerns have highlighted the need to cent in Orissa, 7.4 per cent in Andhra Pradesh, 5.5 per identify substitutes for traditional timbers. It is in this context cent in Karnataka and the balance is spread in other States. bamboo assumes special significance. Bamboos are aptly Diversified uses of bamboos : Bamboos are employed called the poor man’s timber and are found in great for a variety of uses, these are the followings : abundance. The word bamboo comes from the Kannada Food purpose : (a) A kind of food in Thailand is glutinous term bambu. Bamboo is a flowering, perennial, evergreen rice with sugar and coconut cream is specially prepared plant in the grass family Poaceae, sub-family bamboo sections of different diameters and lengths, (b) Bambusoideae, Their strength, straightness and lightness The shoots (new culms that come out of the ground) of combined with extraordinary hardness, range in sizes, bamboo are used in numerous Asian dishes and thin soups abundance, easy and are available in various propagation and the short sliced forms, (c) The period in which they attain bamboo shoot in its maturity make them suitable fermented state forms an for a variety of purposes. -

Gum Naval Stores: Turpentine and Rosin from Pine Resin

- z NON-WOOD FORESTFOREST PRODUCTSPRODUCTS ~-> 2 Gum naval stores:stores: turpentine and rosinrosin from pinepine resinresin Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unaed Nations N\O\ON- -WOODWOOD FOREST FOREST PRODUCTSPRODUCTS 22 Gum navalnaval stores:stores: turpentine• and rosinrosin from pinepine resinresin J.J.W.J.J.W. Coppen andand G.A.G.A. HoneHone Mi(Mf' NANATURALTURAL RESRESOURCESOURCES INSTITUTEIN STITUTE FFOODOOD ANDAN D AGRICULTUREAGRIC ULTURE ORGANIZATIONORGANIZATION OFOF THETH E UNITEDUNITED NATIONSNATIONS Rome,Rome, 19951995 The designationsdesignations employedemployed andand thethe presentationpresentation of of materialmaterial inin thisthis publication do not imply the expression of any opinionopinion whatsoever onon thethe partpart ofof thethe FoodFood andand AgricultureAgriculture OrganizationOrganization ofof thethe UnitedUnited Nations concernconcerninging thethe legal status of any countrycountry,, territory, city or areaareaorofits or of its auauthorities,thorities, orconcerningor concerning the delimitationdelirnitation of itsits frontiers or boundaries.boundaries. M-37M-37 IISBNSBN 92-5-103684-5 AAllll rights reserved.reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrretrievalieval systemsystem,, oror transmitted inin any form or byby anyany means,means, electronic,electronic, mechanimechanicai,cal, photocphotocopyingopying oror otherwise, withoutwithout thethe prior permission ofof the copyright owner. AppApplicationslications forfor such permission,permission, with a statementstatement -

Creating a Forest Garden Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops

Creating a Forest Garden Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops Martin Crawford Contents Foreword by Rob Hopkins 15. Ground cover and herbaceous perennial species Introduction 16. Designing the ground cover / perennial layer 17. Annuals, biennials and climbers Part 1: How forest gardens work 18. Designing with annuals, biennials and climbers 1. Forest gardens Part 3: Extra design elements and maintenance 2. Forest garden features and products 3. The effects of climate change 19. Clearings 4. Natives and exotics 20. Paths 5. Emulating forest conditions 21. Fungi in forest gardens 6. Fertility in forest gardens 22. Harvesting and preserving 23. Maintenance Part 2: Designing your forest garden 24. Ongoing tasks 7. Ground preparation and planting Glossary 8. Growing your own plants 9. First design steps Appendix 1: Propagation tables 10. Designing wind protection Appendix 2: Species for windbreak hedges 11. Canopy species Appendix 3: Plants to attract beneficial insects and bees 12. Designing the canopy layer Appendix 4: Edible crops calendar 13. Shrub species 14. Designing the shrub layer Resources: Useful organisations, suppliers & publications Foreword In 1992, in the middle of my Permaculture Design Course, about 12 of us hopped on a bus for a day trip to Robert Hart’s forest garden, at Wenlock Edge in Shropshire. A forest garden tour with Robert Hart was like a tour of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory with Mr Wonka himself. “Look at this!”, “Try one of these!”. There was something extraordinary about this garden. As you walked around it, an awareness dawned that what surrounded you was more than just a garden – it was like the garden that Alice in Alice in Wonderland can only see through the door she is too small to get through: a tangible taste of something altogether new and wonderful yet also instinctively familiar. -

Wealth Creation Through Bamboo Renewable Power and Biochar

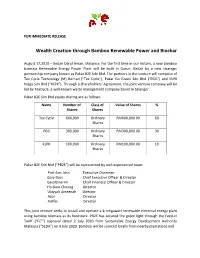

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wealth Creation through Bamboo Renewable Power and Biochar August 17,2020 – Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia: For the first time in our history, a new bamboo biomass Renewable Energy Power Plant will be built in Gurun, Kedah by a new strategic partnership company known as Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd. The partners in the venture will comprise of Tex Cycle Technology (M) Berhad (“Tex Cycle”), Pakar Go Green Sdn Bhd (“PGG”) and KLPK Niaga Sdn Bhd (“KLPK”). Through a Shareholders’ Agreement, the joint venture company will be led by TexCycle, a well-known waste management company based in Selangor. Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd equity sharing are as follows: Name Number of Class of Value of Shares % Shares Shares Tex Cycle 600,000 Ordinary RM600,000.00 60 Shares PGG 300,000 Ordinary RM300,000.00 30 Shares KLPK 100,000 Ordinary RM100,000.00 10 Shares Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd (“PB2E”) will be represented by well experienced team: Prof Azni Idris Executive Chairman Gary Dass Chief Executive Officer & Director Geraldine Hii Chief Financial Officer & Director Ho Siew Choong Director ‘Atiyyah Ameenah Director Azizi Director Ariffin Director This joint venture seeks to install and operate a 4-megawatt renewable electrical energy plant using bamboo biomass as its feedstock. PB2E has secured the green light through the Feed-in Tariff (“FiT”) approval dated 2 July 2020 from Sustainable Energy Development Authority Malaysia (“SEDA”) on 9 July 2020. Bamboo will be sourced locally from nearby plantations and supported by newly developed 1000 hectares of future bamboo farm initiated by KLPK in tandem with the current plan under the YAB Menteri Besar of Kedah. -

Effects of Different Bamboo Forest Spaces on Psychophysiological

Article Effects of Different Bamboo Forest Spaces on Psychophysiological Stress and Spatial Scale Evaluation Wei Lin, Qibing Chen *, Xiaoxia Zhang, Jinying Tao, Zongfang Liu, Bingyang Lyu , Nian Li, Di Li and Chengcheng Zeng College of Landscape Architecture, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (N.L.); [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (C.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0288-265-2175 Received: 10 May 2020; Accepted: 28 May 2020; Published: 1 June 2020 Abstract: Forests are large-scale green space resources that may exert a positive impact on human physiology and psychology. Forests can be divided into mixed forest and pure forest, according to the number of dominant tree species. Pure forest offers specific advantages for the study of spatial structure and scale. In this study, a type of pure forest (i.e., bamboo forest) was adopted as a research object to investigate differences in the physiological and psychological responses of psychologically pressured college students to different types of forest space. We recruited 60 participants and randomly assigned them to three experimental groups: forest interior space (FIS), forest external space (FES) and forest path space (FPS). All participants were asked to perform the same pre-test task but different post-test tasks. The pre-test involved performing a pressure-inducing task, whereas the post-test involved viewing photographs of each space type. The same indicators were measured in both the pre- and post-test, including a β/α index from each lobe, positive emotion, negative emotion and total mood disturbance (TMD) values, according to the profile of mood states (POMS), in addition to spatial scale preferences obtained through a questionnaire and interviews.