Global Environment Facility (GEF) Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Guidelines

Contents S. No. Description Page 1. Background 3 2. Review of the earlier NBM and Issues to be addressed 3 3. Objectives 6 4. Strategy 7 5. Key Outputs 8 6. Mission Structure 9 I) National Level 9 Executive Committee 9 Sub Committee 1 10 Sub Committee 2 10 National Bamboo Mission Cell 11 Bamboo Technical Support Group 11 II) State Level 12 State Level Executive Committee 12 State Bamboo Mission 13 III) District Level 14 7. Preparation of Action Plan and Approvals 15 8. Monitoring & Evaluation 15 9. Funding Pattern 16 10. Mission Intervention 16 10.1 Research & Development 17 10.2 Plantation development 18 10.2.1 Establishment of Nurseries 19 10.2.2 Certified Planting Material 19 10.2.3 Nurseries 19 10. 2.4 Raising New Plantations 20 10. 3 Extension, Education and Skill Development 20 10. 4 Micro-Irrigation 21 10.5 Post-harvest storage and treatment facilities 21 10.6 Promotion and Development of Infrastructure for Bamboo 22 Market 10. 7 Bamboo Market Research 22 10.8 . Incubation Centres 23 Page 1 of 40 10.9 . Production, Development & Processing 23 10.10 Role of Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) & Other Agencies for 23 Capacity Building 10.11 Export of Bamboo Based Products 23 Annexure I: State wise list of infrastructure created in earlier NBM Annexure II: Intervention for implementation role of Ministries/ Departments Annexure III: Indicative BTSG Component Annexure IV: Interventions with cost norms and funding pattern Annexure V: Format for submission of Annual Action Plan Annexure VI: Format for application for the approval of Executive Committee Page 2 of 40 OPERATIONAL GUIDELINES OF RESTRUCTURED NATIONAL BAMBOO MISSION 1. -

Book of Abstracts.Pdf

1 List of presenters A A., Hudson 329 Anil Kumar, Nadesa 189 Panicker A., Kingman 329 Arnautova, Elena 150 Abeli, Thomas 168 Aronson, James 197, 326 Abu Taleb, Tariq 215 ARSLA N, Kadir 363 351Abunnasr, 288 Arvanitis, Pantelis 114 Yaser Agnello, Gaia 268 Aspetakis, Ioannis 114 Aguilar, Rudy 105 Astafieff, Katia 80, 207 Ait Babahmad, 351 Avancini, Ricardo 320 Rachid Al Issaey , 235 Awas, Tesfaye 354, 176 Ghudaina Albrecht , Matthew 326 Ay, Nurhan 78 Allan, Eric 222 Aydınkal, Rasim 31 Murat Allenstein, Pamela 38 Ayenew, Ashenafi 337 Amat De León 233 Azevedo, Carine 204 Arce, Elena An, Miao 286 B B., Von Arx 365 Bétrisey, Sébastien 113 Bang, Miin 160 Birkinshaw, Chris 326 Barblishvili, Tinatin 336 Bizard, Léa 168 Barham, Ellie 179 Bjureke, Kristina 186 Barker, Katharine 220 Blackmore, 325 Stephen Barreiro, Graciela 287 Blanchflower, Paul 94 Barreiro, Graciela 139 Boillat, Cyril 119, 279 Barteau, Benjamin 131 Bonnet, François 67 Bar-Yoseph, Adi 230 Boom, Brian 262, 141 Bauters, Kenneth 118 Boratyński, Adam 113 Bavcon, Jože 111, 110 Bouman, Roderick 15 Beck, Sarah 217 Bouteleau, Serge 287, 139 Beech, Emily 128 Bray, Laurent 350 Beech, Emily 135 Breman, Elinor 168, 170, 280 Bellefroid, Elke 166, 118, 165 Brockington, 342 Samuel Bellet Serrano, 233, 259 Brockington, 341 María Samuel Berg, Christian 168 Burkart, Michael 81 6th Global Botanic Gardens Congress, 26-30 June 2017, Geneva, Switzerland 2 C C., Sousa 329 Chen, Xiaoya 261 Cable, Stuart 312 Cheng, Hyo Cheng 160 Cabral-Oliveira, 204 Cho, YC 49 Joana Callicrate, Taylor 105 Choi, Go Eun 202 Calonje, Michael 105 Christe, Camille 113 Cao, Zhikun 270 Clark, John 105, 251 Carta, Angelino 170 Coddington, 220 Carta Jonathan Caruso, Emily 351 Cole, Chris 24 Casimiro, Pedro 244 Cook, Alexandra 212 Casino, Ana 276, 277, 318 Coombes, Allen 147 Castro, Sílvia 204 Corlett, Richard 86 Catoni, Rosangela 335 Corona Callejas , 274 Norma Edith Cavender, Nicole 84, 139 Correia, Filipe 204 Ceron Carpio , 274 Costa, João 244 Amparo B. -

Dear Readers Welcome to the 30Th Issue of Produce Vegetable Oil

Dear readers Welcome to the 30th issue of produce vegetable oil. The oil is not We continue to feature APANews! This issue includes several only rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and developments in agroforestry interesting articles on recent potassium, but can also be education and training through the developments in agroforestry. We converted into industrial biodiesel. SEANAFE News. Articles in this issue also have several contributions This article is indeed timely as recent of SEANAFE News discuss about presenting findings of agroforestry research efforts are focusing on projects on landscape agroforestry, research. alternative sources of fuel and and marketing of agroforestry tree energy. products. There are also updates on Two articles discuss non-wood forest its Research Fellowship Program and products in this issue. One article Another article presents the results reports from the national networks of features the findings of a research of a study that investigated the SEANAFE’s member countries. that explored various ways of storing physiological processes of rattan seeds to increase its viability. agroforestry systems in India. The There are also information on The article also presents a study focused on photosynthesis and upcoming international conferences comprehensive overview of rattan other related growth parameters in agroforestry which you may be seed storage and propagation in that affect crop production under interested in attending. Websites Southeast Asia. tree canopies. and new information sources are also featured to help you in your Another article discusses the In agroforestry promotion and various agroforestry activities. potential of integrating Burma development, the impacts of a five- bamboo in various farming systems year grassroots-oriented project on Thank you very much to all the in India. -

Bamboo Cultivation RASHTRIYA KRISHI Volume 10 Issue 1 June, 2015 47-49 E ISSN–2321–7987 | Article |Visit Us

Bamboo Cultivation RASHTRIYA KRISHI Volume 10 Issue 1 June, 2015 47-49 e ISSN–2321–7987 | Article |Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in| Bamboo cultivation : Generating income for the rural poor Hiralal Jana Department of Agricultural Extension, College of Agriculture, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, BURDWAN (W.B.) INDIA (Email: [email protected]) Diminishing resources and availability of forest wood Madhya Pradesh, 9.90 per cent in Maharashtra, 8.7 per and conservation concerns have highlighted the need to cent in Orissa, 7.4 per cent in Andhra Pradesh, 5.5 per identify substitutes for traditional timbers. It is in this context cent in Karnataka and the balance is spread in other States. bamboo assumes special significance. Bamboos are aptly Diversified uses of bamboos : Bamboos are employed called the poor man’s timber and are found in great for a variety of uses, these are the followings : abundance. The word bamboo comes from the Kannada Food purpose : (a) A kind of food in Thailand is glutinous term bambu. Bamboo is a flowering, perennial, evergreen rice with sugar and coconut cream is specially prepared plant in the grass family Poaceae, sub-family bamboo sections of different diameters and lengths, (b) Bambusoideae, Their strength, straightness and lightness The shoots (new culms that come out of the ground) of combined with extraordinary hardness, range in sizes, bamboo are used in numerous Asian dishes and thin soups abundance, easy and are available in various propagation and the short sliced forms, (c) The period in which they attain bamboo shoot in its maturity make them suitable fermented state forms an for a variety of purposes. -

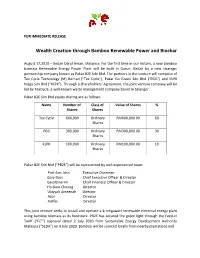

Wealth Creation Through Bamboo Renewable Power and Biochar

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wealth Creation through Bamboo Renewable Power and Biochar August 17,2020 – Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia: For the first time in our history, a new bamboo biomass Renewable Energy Power Plant will be built in Gurun, Kedah by a new strategic partnership company known as Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd. The partners in the venture will comprise of Tex Cycle Technology (M) Berhad (“Tex Cycle”), Pakar Go Green Sdn Bhd (“PGG”) and KLPK Niaga Sdn Bhd (“KLPK”). Through a Shareholders’ Agreement, the joint venture company will be led by TexCycle, a well-known waste management company based in Selangor. Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd equity sharing are as follows: Name Number of Class of Value of Shares % Shares Shares Tex Cycle 600,000 Ordinary RM600,000.00 60 Shares PGG 300,000 Ordinary RM300,000.00 30 Shares KLPK 100,000 Ordinary RM100,000.00 10 Shares Pakar B2E Sdn Bhd (“PB2E”) will be represented by well experienced team: Prof Azni Idris Executive Chairman Gary Dass Chief Executive Officer & Director Geraldine Hii Chief Financial Officer & Director Ho Siew Choong Director ‘Atiyyah Ameenah Director Azizi Director Ariffin Director This joint venture seeks to install and operate a 4-megawatt renewable electrical energy plant using bamboo biomass as its feedstock. PB2E has secured the green light through the Feed-in Tariff (“FiT”) approval dated 2 July 2020 from Sustainable Energy Development Authority Malaysia (“SEDA”) on 9 July 2020. Bamboo will be sourced locally from nearby plantations and supported by newly developed 1000 hectares of future bamboo farm initiated by KLPK in tandem with the current plan under the YAB Menteri Besar of Kedah. -

International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR)

Good practices, success stories and lessons learned on implementation of the UN Strategic Plan for Forests and the Global Forest Goals Input received from INBAR - International Network for Bamboo and Rattan • Reforestation using bamboo in Chishui, China • Comparing the eco-cost of bamboo, teak and acacia charcoal in Ghana • Bamboo for land restoration in India • Bamboo charcoal in Tanzania Reforestation using bamboo in Chishui, China Bamboo is a key part of the Chinese government’s flagship reforestation programme in Chishui, Guizhou. Goals and targets addressed BAMBOO, FORESTS AND LAND: the advantages of UNFF Global Forest Goals 1 (Reverse the bamboo loss of forest cover worldwide), 2 With over 30 million hectares and 1600 species spread (Enhance forest-based economic, social across the world, bamboo offers a naturally abundant, and environmental benefits), 3 (Increase strategic tool for land restoration and reforestation. the area of protected forests worldwide), Restoring degraded land. Bamboo has extensive root 5 (Promote governance frameworks to systems, which can measure up to 100 kilometres per implement sustainable forest hectare of bamboo and live for around a century. This management) underground biomass makes bamboo capable of Background surviving and regenerating, even when the biomass above ground is destroyed. Launched in 1999, China’s Conversion of Cropland into Forest Programme (CCFP) Raising water levels. When properly selected and well was a response to a number of ecological managed, bamboo species can help raise the crises and growing environmental groundwater table level significantly and reduce water challenges. Its main aim was to restore run-off. Bamboo is tolerant to both floods and droughts. -

Rwanda Green Well Potential for Investment In

Rwanda’s Green Well Opportunities to engage private sector investors in Rwanda’s forest landscape restoration Global Forest and Climate Change Programme Rwanda’s Green Well Opportunities to engage private sector investors in Rwanda’s forest landscape restoration i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or other participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organisations. This report has been produced by IUCN’s Global Forest and Climate Change Programme, funded by UKaid from the UK government. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: IUCN (2015). Rwanda’s Green Well: Opportunities to engage private sector investors in Rwanda’s forest landscape restoration. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xii+85pp. Cover Photo: Craig Beatty/IUCN 2016 Layout by: Chadi Abi Available From: IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Global Forest and Climate Change Programme Rue Mauverney 28 1196 Gland, Switzerland [email protected] www.iucn.org/FLR ii Executive summary Rwanda has pledged to plant two million Rwanda has a complex policy environment as hectares of trees by 2020. -

Living with Wood to the Participants and the General Public

REDISCOVERING WOOD: THE KEY TO A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE ART AND JOY OF WOOD BANGALORE, INDIA 19 OCTOBER – 22 OCTOBER 2011 PROCEEDINGS PART 1- CONFERENCE OVERVIEW The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107598-2 (print) E-ISBN 978-92-5-107599-9 (PDF) © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence- request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Report on the Situation Potential and Prospect of Bamboo Industry In

Dr. & Prof. Ding Xingcui China National Bamboo Research Center June 16, 2020 1 Preface Our age has been one ubiquitously harassed by adverse climate changes that no country or community on this planet could stay intact. Behind the more and more relentless ravages of our national economies, lives and people’s safety is the fact that our planet is being tormented by changing weather patterns, rising sea levels, more extreme weather events and unprecedented greenhouse gas emissions. If we stay as unresponsive to them as before, the world’s average surface temperature is likely to rise by 3 degrees centigrade within this century. Among the victimized populations, the poorest and the most vulnerable people are the most pathetic ones. Affordable, scalable solutions are now available to enable countries to leapfrog to cleaner, more resilient economies. Renewable energy and other emission-reducing and adaptation- oriented measures, as embraced by more and more people, represent our faster and faster paces to alleviate and mend the damages. However, climate change is a global challenge disregarding national borders that no low-carbon economy in the real sense could be developed in the developing countries without viable solution based on international coordination. On the International Day of Forests (21 March), UN chief António Guterres is calling for 2020, which has been referred to as a “nature super year”, to be the year that the world turns the tide on deforestation and forestry loss.1 While the outrageous degradation of forest on our planet, and the environment as a whole, is precluding our sustainable development, our overconsumption of natural resources are accelerating the biodiversity loss and exacerbating climate changes, according to the UN chief. -

Biodiversity in Bamboo Forests: a Policy Perspective for Long Term Sustainability

INBAR Working Paper 59 Bamboo forests are unique in their ability to meet economic and social objectives of providing timber, development and raising rural incomes rapidly and over a sustained period of time. China’s example has shown that by changing their management practices, farmers are able to get richer through significantly increasing the supply of timber to markets without depleting the source of this timber - a relatively uncommon phenomenon in the forestry sector. However, recent changes in practices are altering bamboo forest structure and biodiversity with negative effects. INBAR’s Bamboo Biodiversity Project examined current practices and policies to determine causes, as well as interventions to halt the loss in biodiversity and subsequent degradation of forests. This report presents the project’s general findings, and suggests what changes are needed to ensure healthy development of China’s bamboo forests, as a key component to its forestry sector. Biodiversity in Bamboo Forests: a policy perspective for long term sustainability Lou Yiping & Giles Henley INBAR Working Paper 59 Table of Contents Biodiversity in Bamboo Forests: a policy perspective for long term sustainability A case study on the implications of China’s forestry policies for biodiversity in bamboo forests INBAR Contents The International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR) is an intergovernmental Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................................................i -

Plant Sciences: Network in Health and Environment (PSNHE-2018) NATIONAL CONFERENCE

National Conference on Plant Sciences: Network in Health and Environment (PSNHE-2018) NATIONAL CONFERENCE On Plant Sciences: Network in Health and Environment (PSNHE-2018) (October 30-31st, 2018) ABSTRACT BOOK SPONSORED BY ORGANIZED BY ESTD. 1892 POST GRADUATE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY KHALSA COLLEGE AMRITSAR (AN AUTONOMOUS COLLEGE) NAAC Reaccrediated ‘A’ Grade (CGPA) ‘College with Potential for Excellence’ Status Conferred by UGC ‘Star Status’ Conferred by Dept. of Biotechnology, G.O.I., New Delhi National Conference on Plant Sciences: Network in Health and Environment (PSNHE-2018) POST GRADUATE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY KHALSA COLLEGE AMRITSAR (O): +91-183-5015511 E-mail: [email protected] : +91-183-2258097 Web: www.khalsacollegeamritsar.org Pin: 143002 (Pb.) India Preface Modern civilization rests on successful and sustained cultivation of plants and wise use of biological and physical resources. Since time immemorial, plants have been collected, traded and bred for new combination of traits. Plants are important in regulating the climatic conditions. As a component of nature, plants are providing solutions to agriculture, health and environment including climate change, food security and as renewable energy sources. “PSNHE-2018” is aimed at providing a platform for adoption and diffusion of research in the upcoming areas of plant sciences. It will disseminate knowledge among researchers, academicians and environmentalists. “PSNHE-2018” will be precursor to understand specific and complete technologies and chart a roadmap for future. The recommendations of the conference will be communicated to the policy makers in the government and other stake holders, with the aim of taking a step forward in finding solutions and new pathways for future potential medicines and climate related issues. -

Bamboo Cultivation in Tripura

BAMBOO CULTIVATION IN TRIPURA Background: Bamboos are popularly known as green gold & poorman’s timber and can generally adapt to wide range of climatic and edaphic conditions. The North Eastern state represents 28% of the countries bamboo stock and Tripura has 2397 sq. Km of bamboo forests forming about 23% geographical area of the state. Muli bamboo comprises about 80% of the bamboo resources and this is the only single stand- bamboo (non-clump forming) most widely used species in the state. Details of Initiatives Bamboo is the most important non timber forest produce used extensively by tribal and rural people of Tripura and plays an important role in employment generation and socio-economic upliftment in rural sector. It is estimated that around 6.1 million mandays is generated per year by way of harvesting and utilisation of bamboo in different forms Bamboo species available in Tripura: 21 species of bamboos are found in Tripura. Most common bamboos are; Muli (Melocanna baccifera), Barak (Bambusa balcooa), Bari (Bambusa polymorpha), Mritinga (Bambusa tulda), Paora (Bambusa teres), Rupai (Dendrocalamus longispathus), Dolu (Neohuzeaua dullooa), Makal (Bambusa pallida), Pecha (Dendrocalamus hamiltonii), Kanak kaich (Bambusa affinis), Jai (Bambusa spp.) Cultivation of Bamboo Bamboo can be vegetatively propagated through rhizome planting, branch cutting, culm cutting and even through tissue culture. Bamboo flowers after long intervals and hence availability of bamboo seed is less. As after flowering culm dies so seed collection and cultivation of bamboo through seeds is recommended in course of bamboo flowering. Achievements of the Initiatives Bamboo plantation raised by Forest Department A total of 50828 ha plantation has been raised so far including 3147 ha in private land through different Schemes of National Afforestation Project, JICA, IGDC, Tripura Bamboo Mission, Rural Development, ADC and National bamboo Mission schemes etc.