The Wildfowl Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSNZ News Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the Members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.)

Supplement to Notornis, Vol. 25, Part 3, September 1978 OSNZ news Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.). No. 8 September 1978 NOTE: Next deadline is earlier to try to beat the Christmas and January shut- Deadline for the December issue will be down of printers and have NOTORNIS 20 November. and OSNZ NEWS out early in 1979. DACHICKS Rough estimates: northland 150-200; The 1978 inquiry into the NZ Dabchick has gone remarkably well, with North Island Volcanic Plateau 600-800; South Taranakii members putting in a lot of time, often with meagre results, in order to help form an overall Wanganui 30; ManawatulWairarapa 300; picture of the status and habits of this species. GisborneiHawkes Bay 50. Total 1 150-1400. We began with a series of questions, to which we now have much better answers. If We thus already have a fairly good base members can stand it, we need another year's effort to confirm and clarify these answers. line agalnst which to measure any major changes in the future. Another year's f~eld 1. Is the NZ Dabchick extinct in the South Island? Answer, apparently yes. Was it ever work should cons~derably Improve the strong there? Possibly not (see Oliver). accuracy of our knowledge. 2. Does the North Island population reach a total of 1000? Answer, yes. Est~matedtotal Regional activity (very rough, see below) 1 1 50-1400 birds. We have no up-tb-date report from Far 3. Are Australian grebelets taking over? Answer, in North Island, not yet. -

Iourgl).\~S • 20AT0712

HIGH TIDE ~ LOW TIO[ -7-68 5-7-613 6 AT 1318 13ATI942 e I AT 0118 ~IOURGl).\~S • 20AT0712 K\oIAJAlEIN. MA.RSHALL ISLANDS MOttO ... T M... v 6, 1968 WASHINGTON (UP1)--PI!ESIDENT JOHN Saigon Fighting in Secon~ Day; SON SUMMONED AMBASSADO~S AVERELL HAII_ Tax Increase Approved RI~AN AND CYRUS VANCE TO THE WHITE HoUSE TODAY TO DISCUSS THE FORTHCOM With Spending Cut Red Offensive on Nation-Wide Scale ING US TALKS WITH NORTH VIET NAM IN SAIGON (UPI)~~NoRTH VIETNAMESE: AND VIET CONG TROOPS FIGHTING AT THE EDGE or PARIS WASHINGTON (lfIl)--THE SENATE ... ND HOUSEl THE CAPITAL FIRED AT LEAST SIX ROCI\[TS AN~ MORTAR INTO HI[ HEART or SAIGON TO- THE TWO EN~OYS WHO H~~t 6EEN N~MEO T ... )(WRITERS, WHO BLOCKED PRESIOENT JOHN BY THE PRESIDENT TO REPRESENT TtlE SON'S PROPOSED TAX SURCH ... RGE FOR NINE '" US. MILITARY POLICE SAID THE SHELLS STRUCK THE CITY FOLLOWING DAY-LONG FIGHT- UNITED ST~TES IN THE INITI~L DISCUS· MONTHS, CHANGED THEIR "'INDS TODAY AND ING 4ROUNO THE Ol;TSKIRTS, BUT rOR THE SECOND TIME IN THEIR 1'''O_O"Y OFfENSIVE THE SIONS WITH. NORTH VIErN~MESE DIPLOMATS, ... PPROVED ... $10 BILLION INCOME HX IN_ COMMUNISTS FAilED TO STRIKE MAJOR TARGETS ARE EXPECTED TO LEAVE rOR PARIS SHORT- CREASE COUPLED WITH'" $4 BILLION SPEND THE SHELLS CAME WHIRLING INTO THE CITY BEFORE MIDNIGHT AND MORE T~N AN HOUR ING CUT LATER THE ~S S~IO THERE WERE NO REPORTS OF C~SU~LTIES fRENCH GOVERNMENT SOURCES S~IO TO· THE "'CTION BY THE HOUSE WAYS .. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

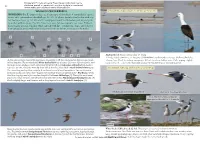

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Clare Ecodistrict 730 40

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Clare Ecodistrict 730 40 © Crown Copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, 2014. Ecological Landscape Analysis, Ecodistrict 730: Clare Prepared by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Authors: Western Region DNR staff ISBN 978-1-55457-598-5 This report, one of 38 for the province, provides descriptions, maps, analysis, photos and resources of the Clare Ecodistrict that can help landowners and planners understand important characteristics of the landscape. The report details the main elements in the ecodistrict and, of particular interest to woodland owners, vegetation types within forest stands. Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) is a first step in developing an ecosystem approach to managing resource values at a landscape level. It supports planning by landowners wanting to understand how their land fits into the landscape ecosystem. Additional direction will be provided by a landscape planning guide, and internet-based inventory update system, both of which are currently under development. The ELAs were analyzed and written from 2005 – 2009. They provide baseline information for this period in a standardized framework of ecosystem mapping and data summary designed to support future data updates, forecasts and trends. This document includes Part 1 – Learning about what makes this ecodistrict distinctive – and Part 2 – How woodland owners can apply landscape concepts to their woodland. Part 3 – Greater detail for forest planners and analysts – will be available on request by contacting DNR officials -

Nocturnal Roost on South Carolina Coast Supports Nearly Half of Atlantic Coast Population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius Hudsonicus During Northward Migration

research paper Wader Study 128(2): xxx–xxx. doi:10.18194/ws.00228 Nocturnal roost on South Carolina coast supports nearly half of Atlantic coast population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus during northward migration Felicia J. Sanders1, Maina C. Handmaker2, Andrew S. Johnson3 & Nathan R. Senner2 1South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, 220 Santee Gun Club Road, McClellanville, SC 29458, USA. [email protected] 2Dept. of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, 715 Sumter Street, Columbia, SC 29208, USA 3Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, New York 14850, USA Sanders, F.J., M.C. Handmaker, A.S. Johnson & N.R. Senner. Nocturnal roost on South Carolina coast supports nearly half of Atlantic coast population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus during northward migration. Wader Study 128(2): xxx–xxx. Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus are rapidly declining and understanding Keywords their use of migratory staging sites is a top research priority. Nocturnal roosts are site fidelity an essential, yet often overlooked component of staging sites due to their apparent rarity, inaccessibility, and inconspicuousness. The coast of Georgia and stopover South Carolina is one of two known important staging areas for Atlantic coast staging area Whimbrel during spring migration. Within this critical staging area, we discovered the largest known Whimbrel nocturnal roost in the Western Hemisphere at population estimate Deveaux Bank, South Carolina. Surveys in 2019 and 2020 during peak spring management migration revealed that Deveaux Bank supports at least 19,485 roosting Whimbrel, conservation which represents approximately 49% of the estimated eastern population of Whimbrel and 24% of the entire North American population. -

12 Boterdijk

12 Boterdijk At Boterdijk, near Roermondsplein, is an Airborne pillar, a memorial to the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions and their efforts in the after- noon of 18 and the morning of 19 September 1944 to join their com- rades at the bridge. The pillar marks the farthest point these British parachutists managed to reach. After the Rhine Bridge’s northern ramp was secured by British units in the evening and night of the 17th, other troops made further at- tempts to break through to the bridge over the following days in or- der to bolster the allied positions. On Monday 18 September two groups from the 3rd Parachute Battalion would get as far as Boter- dijk. Involved was a group led by Lieutenant John Dickson and a group led by Major Anthony Deane-Drummond. Next day they would be taken prisoner. On Tuesday 19 September companies of the 1st Parachute Battalion tried to get to the Rhine Bridge. ‘S’ Company ca- me to within 800 metres of the Rhine Bridge, but by then had too few men and too little fire-power to continue its advance. In this sto- ry the tale of these groups is depicted using war diaries and recollec- tions of British soldiers who were there. Dickson’s group Deane-Drummond’s group Units of the 1st Parachute Battalion in the attack 'S' Company R Company Making the balance Dickson’s group Map showing the situation around Boterdijk in 1944 (Copyright Cartographic Bureau MAP/Bert Stamkot) In the afternoon of 18 September the 3rd Parachute Battalion failed in its efforts to break through the German defence line al- ong Noordelijke Parallelweg and over Utrechtseweg. -

In the Cape Verde Islands

ZOOLOGIA CABOVERDIANA REVISTA DA SOCIEDADE CABOVERDIANA DE ZOOLOGIA VOLUME 5 | NÚMERO 1 Abril de 2014 ZOOLOGIA CABOVERDIANA REVISTA DA SOCIEDADE CABOVERDIANA DE ZOOLOGIA Zoologia Caboverdiana is a peer-reviewed open-access journal that publishes original research articles as well as review articles and short notes in all areas of zoology and paleontology of the Cape Verde Islands. Articles may be written in English (with Portuguese summary) or Portuguese (with English summary). Zoologia Caboverdiana is published biannually, with issues in spring and autumn. For further information, contact the Editor. Instructions for authors can be downloaded at www.scvz.org Zoologia Caboverdiana é uma revista científica com arbitragem científica (peer-review) e de acesso livre. Nela são publicados artigos de investigação original, artigos de síntese e notas breves sobre zoologia e paleontologia das Ilhas de Cabo Verde. Os artigos podem ser submetidos em inglês (com um resumo em português) ou em português (com um resumo em inglês). Zoologia Caboverdiana tem periodicidade bianual, com edições na primavera e no outono. Para mais informações, deve contactar o Editor. Normas para os autores podem ser obtidas em www.scvz.org Chief Editor | Editor principal Dr Cornelis J. Hazevoet (Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Portugal); [email protected] Editorial Board | Conselho editorial Dr Joana Alves (Instituto Nacional de Saúde Pública, Praia, Cape Verde) Prof. Dr G.J. Boekschoten (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Dr Eduardo Ferreira (Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal) Rui M. Freitas (Universidade de Cabo Verde, Mindelo, Cape Verde) Dr Javier Juste (Estación Biológica de Doñana, Spain) Evandro Lopes (Universidade de Cabo Verde, Mindelo, Cape Verde) Dr Adolfo Marco (Estación Biológica de Doñana, Spain) Prof. -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

British Birds |

VOL. LU JULY No. 7 1959 BRITISH BIRDS WADER MIGRATION IN NORTH AMERICA AND ITS RELATION TO TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS By I. C. T. NISBET IT IS NOW generally accepted that the American waders which occur each autumn in western Europe have crossed the Atlantic unaided, in many (if not most) cases without stopping on the way. Yet we are far from being able to answer all the questions which are posed by these remarkable long-distance flights. Why, for example, do some species cross the Atlantic much more frequently than others? Why are a few birds recorded each year, and not many more, or many less? What factors determine the dates on which they cross? Why are most of the occurrences in the autumn? Why, despite the great advantage given to them by the prevail ing winds, are American waders only a little more numerous in Europe than European waders in North America? To dismiss the birds as "accidental vagrants", or to relate their occurrence to weather patterns, as have been attempted in the past, may answer some of these questions, but render the others still more acute. One fruitful approach to these problems is to compare the frequency of the various species in Europe with their abundance, migratory behaviour and ecology in North America. If the likelihood of occurrence in Europe should prove to be correlated with some particular type of migration pattern in North America this would offer an important clue as to the causes of trans atlantic vagrancy. In this paper some aspects of wader migration in North America will be discussed from this viewpoint. -

HUDSONIAN WHIMBREL at FAIR ISLE by KENNETH WILLIAMSON and VALERIE M

HUDSONIAN WHIMBREL AT FAIR ISLE BY KENNETH WILLIAMSON and VALERIE M. THOM (Fair Isle Bird Observatory) WHILST bird-watching over an area of close-cropped grassland at the south end of Fair Isle on 27th May 1955 the writers, together with visitors to the Bird Observatory, disturbed a party of half-a- dozen Whimbrels (Numenius phmopus). As they flew off, V.M.T. remarked that one of the birds was without a white rump. During the remainder of the day, and on the 28th, we kept this party under observation, often at very close quarters from the cover of dry-stone dykes, and were able to satisfy ourselves that the odd bird was an example of the American race, the Hudson- ian Whimbrel (Numenius ph. hudsonicus)—called Hudsonian Curlew in the A.O.U. Checklist. The bird was distinctly smaller than its companions (some of the observers estimated from one-third to one-quarter smaller) and of slenderer build and sleeker appearance. The disparity in size was most obvious when the birds were in flight. The head- markings were similar to those of the European Whimbrel but were more pronounced, due to the paler colour of the cheeks and more complete eye-stripe. In flight, the bird offered a distinctive pattern of dark brown primaries contrasting with paler brown, buff-mottled secondaries and coverts, and a warmer brown mantle, rump and tail. The last, in fact, appeared in some lights to have a russet tinge. The bill was similar in length to the Whirnbrel's, blackish in colour, and strongly decurved over the distal half. -

New Caledonia, Fiji & Vanuatu

Field Guides Tour Report Part I: New Caledonia Sep 5, 2011 to Sep 15, 2011 Phil Gregory The revamped tour was a little later this year and it seemed to make some things a bit easier, note how well we did with the rare Crow Honeyeater, and Kagu was as ever a standout. One first-year bird was rewarded with a nice juicy scorpion that our guide found, and this really is a fabulous bird to see, another down on Harlan's famiy quest, too, as an added bonus to what is a quite unique bird. Cloven-feathered Dove was also truly memorable, and watching one give that strange, constipated hooting call was fantastic and this really is one of the world's best pigeons. Air Calin did their best to make life hard with a somewhat late flight to Lifou, and I have to say the contrast with the Aussie pilots in Vanuatu was remarkable -- these French guys must still be learning as they landed the ATR 42's so hard and had to brake so fiercely! Still, it all worked out and the day trip for the Ouvea Parakeet worked nicely, whilst the 2 endemic white-eyes on Lifou were got really early for once. Nice food, an interesting Kanak culture, with a trip to the amazing Renzo Piano-designed Tjibaou Cultural Center also feasible this The fantastic Kagu, star of the tour! (Photo by guide Phil year, and a relaxed pace make this a fun birding tour with some Gregory) terrific endemic birds as a bonus. My thanks to Karen at the Field Guides office for hard work on the complex logistics for this South Pacific tour, to the very helpful Armstrong at Arc en Ciel, Jean-Marc at Riviere Bleue, and to Harlan and Bart for helping me with my bags when I had a back problem. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

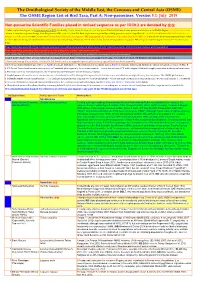

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately.