Labor History: the Astronaut Strike by Ed Leavy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Annotated List of Works Cited Primary Sources Newspapers “Apollo 11 se Vraci na Zemi.” Rude Pravo [Czechoslovakia] 22 July 1969. 1. Print. This was helpful for us because it showed how the U.S. wasn’t the only ones effected by this event. This added more to our project so we had views from outside the US. Barbuor, John. “Alunizaron, Bajaron, Caminaron, Trabajaron: Proeza Lograda.” Excelsior [Mexico] 21 July 1969. 1. Print. The front page of this newspaper was extremely helpful to our project because we used it to see how this event impacted the whole world not just America. Beloff, Nora. “The Space Race: Experts Not Keen on Getting a Man on the Moon.” Age [Melbourne] 24 April 1962. 2. Print. This was an incredibly important article to use in out presentation so that we could see different opinions. This article talked about how some people did not want to go to the moon; we didn’t find many articles like this one. In most everything we have read it talks about the advantages of going to the moon. This is why this article was so unique and important. Canadian Press. “Half-billion Watch the Moon Spectacular.” Gazette [Montreal] 21 July 1969. 4. Print. This source gave us a clear idea about how big this event really was, not only was it a big deal in America, but everywhere else in the world. This article told how Russia and China didn’t have TV’s so they had to find other ways to hear about this event like listening to the radio. -

Apollo Space Suit

APOLLO SPACE S UIT 1962–1974 Frederica, Delaware A HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK SEPTEMBER 20, 2013 DelMarVa Subsection Histor y of the Apollo Space Suit This model would be used on Apollo 7 through Apollo 14 including the first lunar mission of Neil Armstrong and Buzz International Latex Corporation (ILC) was founded in Aldrin on Apollo 11. Further design improvements were made to Dover, Delaware in 1937 by Abram Nathanial Spanel. Mr. Spanel improve mobility for astronauts on Apollo 15 through 17 who was an inventor who became proficient at dipping latex material needed to sit in the lunar rovers and perform more advanced to form bathing caps and other commercial products. He became mobility exercises on the lunar surface. This suit was known as famous for ladies apparel made under the brand name of Playtex the model A7LB. A slightly modified ILC Apollo suit would also go that today is known worldwide. Throughout WWII, Spanel drove on to support the Skylab program and finally the American-Soyuz the development and manufacture of military rubberized products Test Program (ASTP) which concluded in 1975. During the entire to help our troops. In 1947, Spanel used the small group known time the Apollo suit was produced, manufacturing was performed as the Metals Division to develop military products including at both the ILC plant on Pear Street in Dover, Delaware, as well as several popular pressure helmets for the U.S. Air Force. the ILC facility in Frederica, Delaware. In 1975, the Dover facility Based upon the success of the pressure helmets, the Metals was closed and all operations were moved to the Frederica plant. -

Gram, No In-Depth Cross-Correlation of the Voluminous Multidisciplinary Data Has Been Possible

SKYLAB: A BEGINNING NationaZ Aeronautics and Space Ahinistration I Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center "The Eagle has landed; Tranquillity Base here." This simple and now historic message of July 20, 1969, marked the attainment of perhaps the greatest peacetime goal in the history of man. It fulfilled President Kennedy's directive issued some 8 short, hectic years earlier, when he proclaimed on May 25, 1961 : "I bel ieve we should go to the moon . before this decade is out." It marked the culmination of a technically complex engineering accomplishment that began with Mercury and continued uninterrupted through Gemini and prelunar Apollo. The ultimate goal of these efforts was a manned lunar landing. None of these programs had as a major objective the detailed study of man's biomedical responses to the space environment, except in the broadest sense of survival and the ability to live and work effectively in that environment. Nevertheless, throughout each program, information con- cerning man and his new surroundings was obtained wherever possible and whenever practicable, ever mindful of the time constraints imposed by the lunar landing goal and the weight limitations of the launch vehicles. In these few days, the preliminary biomedical results of NASA's Skylab effort have been presented to you. A major goal of Skylab was to learn more about man and his responses to the space environment for missions lasting up to 84 days. The results are necessarily prelimin- ary, for in the short time which has elapsed since the end of the pro- gram, no in-depth cross-correlation of the voluminous multidisciplinary data has been possible. -

Spaceport News John F

Aug. 9, 2013 Vol. 53, No. 16 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe MAVEN arrives, Mars next stop Astronauts By Steven Siceloff Spaceport News gather for AVEN’s approach to Mars studies will be Skylab’s Mquite different from that taken by recent probes dispatched to the Red Planet. 40th gala Instead of rolling about on the By Bob Granath surface looking for clues to Spaceport News the planet’s hidden heritage, MAVEN will orbit high above n July 27, the Astronaut the surface so it can sample the Scholarship Foundation upper atmosphere for signs of Ohosted a dinner at the what changed over the eons and Kennedy Space Center’s Apollo/ why. Saturn V Facility celebrating the The mission will be the first 40th anniversary of Skylab. The of its kind and calls for instru- gala featured many of the astro- ments that can pinpoint trace nauts who flew the missions to amounts of chemicals high America’s first space station. above Mars. The results are Six Skylab astronauts partici- expected to let scientists test pated in a panel discussion dur- theories that the sun’s energy ing the event, and spoke about slowly eroded nitrogen, carbon living and conducting ground- dioxide and water from the Mar- breaking scientific experiments tian atmosphere to leave it the aboard the orbiting outpost. dry, desolate world seen today. Launched unpiloted on May “Scientists believe the planet 14, 1973, Skylab was a complex CLICK ON PHOTO NASA/Tim Jacobs orbiting scientific laboratory. has evolved significantly over NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft rests on a processing the past 4.5 billion years,” said stand inside Kennedy’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility Aug. -

Finding Aid to the William R. Pogue Papers, 1939-2011

FINDING AID TO THE WILLIAM R. POGUE PAPERS, 1939-2011 Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2016 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Processed by: Mary A. Sego, September 12, 2016 Descriptive Summary Creator Information Pogue, William R., 1930-2014 Title William R. Pogue papers Collection Identifier MSP 208 Date Span 1939-2011; predominant, 1963-1994 Abstract Papers documenting aspects of William (Bill) R. Pogue’s career as an astronaut. There are a few items related to nuclear energy, including a copy of a signed letter from Albert Einstein to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in regards to research on the atomic bomb, dated August 2, 1939. Extent 0.30 cubic feet (1 mss box and 1 folder) Finding Aid Author Mary A. Sego, 2016 Languages English Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries Administrative Information Location Information: ASC-R Access Restrictions: Collection is open for research. Acquisition Donated by William R. Pogue, September 27, 2013. Information: Accession Number: 20130927; 20140516 Preferred Citation: MSP 208, William R. Pogue papers, Karnes Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries Copyright Notice: Purdue University per deed of gift. Related Materials William Pogue official website: Information: http://www.williampogue.com/ The Manhattan Project: an interactive history, U.S. Department of Energy – Office of History and Heritage Resources: 9/27/2016 2 https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project- history/Events/1939-1942/einstein_letter.htm 9/27/2016 3 Subjects and Genres Persons Pogue, William R., 1930-2014 Organizations NASA United States Air Force Flights Archives at Purdue University Topics Astronauts Skylab Program Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Form and Genre Types Autobiography Correspondence DVDs Trading cards Occupations Astronaut 9/27/2016 4 Biography of William R. -

Skylab: the Human Side of a Scientific Mission

SKYLAB: THE HUMAN SIDE OF A SCIENTIFIC MISSION Michael P. Johnson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: J. Todd Moye, Major Professor Alfred F. Hurley, Committee Member Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Johnson, Michael P. Skylab: The Human Side of a Scientific Mission. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 115pp., 3 tables, references, 104 titles. This work attempts to focus on the human side of Skylab, America’s first space station, from 1973 to 1974. The thesis begins by showing some context for Skylab, especially in light of the Cold War and the “space race” between the United States and the Soviet Union. The development of the station, as well as the astronaut selection process, are traced from the beginnings of NASA. The focus then shifts to changes in NASA from the Apollo missions to Skylab, as well as training, before highlighting the three missions to the station. The work then attempts to show the significance of Skylab by focusing on the myriad of lessons that can be learned from it and applied to future programs. Copyright 2007 by Michael P. Johnson ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the help of numerous people. I would like to begin, as always, by thanking my parents. You are a continuous source of help and guidance, and you have never doubted me. Of course I have to thank my brothers and sisters. -

Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 288 714 SE 048 726 AUTHOR Hartsfield, John W.; Hartsfield, Kendra J. TITLE Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Cleveland, Ohio. Lewis Research Center. PUB DATE Oct 85 NOTE 126p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; Aerospace Technology; Educational Games; Elementary Education; *Elementary School Science; 'Science Activities; Science and Society; Science Education; *Science History; *Science Instruction; *Space Exploration; Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS *Space Travel ABSTRACT Since its beginning, the space program has caught the attention of young people. This space science activity booklet was designed to provide information and learning activities for students in elementary grades. It contains chapters on:(1) primitive beliefs about flight; (2) early fantasies of flight; (3) the United States human spaceflight programs; (4) a history of human spaceflight activity; (5) life support systems for the astronaut; (6) food for human spaceflight; (7) clothing for spaceflight and activity; (8) warte management systems; (9) a human space flight le;g; and (10) addition 1 activities and pictures. Also included is a bibliography of books, other publications and films, and the answers to the three word puzzles appearing in the booklet. (TW) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT U.S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Activities CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as mewed from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to norm. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 361 202 SE 053 616 TITLE Beyond

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 361 202 SE 053 616 TITLE Beyond Earth's Boundaries INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Kennedy Space Center, FL. John F. Kennedy Space Center. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 214p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; Astronomy; Earth Science; Elementary Education; Elementary School Science; Elementary School Students; Elementary School Teachers; Physics; Resource Materials; *Science Activities; Science History; *Science Instruction; Scientific Concepts; Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS Astronauts; Space Shuttle; Space Travel ABSTRACT This resource for teachers of elementary age students provides a foundation for building a life-long interest in the U.S. space program. It begins with a basic understanding of man's attempt to conquer the air, then moves on to how we expanded into near-Earth space for our benefit. Students learn, through hands-on experiences, from projects performed within the atmosphere and others simulated in space. Major sections include:(1) Aeronautics,(2) Our Galaxy, (3) Propulsion Systems, and (4) Living in Space. The appendixes include a list of aerospace objectives, K-12; descriptions of spin-off technologies; a list of educational programs offered at the Kennedy Space Center (Florida); and photographs. (PR) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** -

US SENATOR ROBERT C. BYRD's ADDRESSES to June30.I994^ ^Jjg

108 STAT. 5106 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—JUNE 30, 1994 SEC. 2. The Speaker of the House and the majority leader of the Senate, acting jointly after consultation with the minority leader of the House and the minority leader of the Senate, shall notify the Members of the House and the Senate, respectively, to reassemble whenever, in their opinion, the public interest shall warrant it. Agreed to June 30, 1994. T ,n ,00. "U.S. SENATOR ROBERT C. BYRD'S ADDRESSES TO [SJune30.i994. Con. Res. 68^] ^jjg UNITED STATES SENATE ON THE HISTORY OF ROMAN CONSTITUTIONALISM"—SENATE PRINT Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concur ring), That there shall be printed as a Senate document "U.S. Senator Robert C. Byrd's Addresses to the United States Senate on the History of Roman Constitutionalism", delivered between May 5, 1993 and October 18, 1993. SEC. 2. The document referred to in the first section shall be- (1) published under the supervision of the Secretary of the Senate; and (2) in such style, form, manner, and binding as directed by the Joint Committee on Printing, after consultation with the Secretary of the Senate. The document shall include illustrations. SEC. 3. In addition to the usual number of copies of the docu ment, there shall be printed the lesser of— (1) 5,000 copies for the use of the Secretary of the Senate; or (2) such number of copies as does not exceed a total produc tion and printing cost of $47,864. Agreed to June 30, 1994. [Hfr'JirL. Con. Res . -

SKYLAB the FORGOTTEN MISSIONS a Senior Honors Thesis

SKYLAB THE FORGOTTEN MISSIONS A Senior Honors Thesis by MICHAEL P. IOHNSON Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs 4 Academic Scholarships Texas ARM University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS April 2004 Major: History SKYLAB THE FORGOTTEN MISSIONS A Senior Honors Thesis by MICHAEL P. JOHNSON Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs & Academic Scholarships Texas A&M University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOW Approved as to style and content by: Jonathan C pers ith Edward A. Funkhouser (Fellows dv' or) (Executive Director) April 2004 Major: History ABSTRACT Skylab The Forgotten Missions. (April 2004) Michael P. Johnson Department of History Texas A&M University Fellows Advisor: Dr. Jonathan Coopersmith Department of History The Skylab program featured three manned missions to America's first and only space station from May 1973 to February 1974. A total of nine astronauts, including one scientist each mission, flew aboard the orbital workshop. Since the Skylab missions contained major goals including science and research in the space environment, the majority of publications dealing with the subject focus on those aspects. This thesis intends to focus, rather, on the human elements of the three manned missions. By incorporating not only books, but also oral histories and interviews with the actual participants, this work contains a more holistic approach and viewpoint. Beginning with a brief history of the development of a space station, this document also follows the path of the nine astronauts to their acceptance into the program. Descriptions of the transition period for NASA from the Moon to a space station, a discussion on the main events of all the missions, and finally a look at the transition to the new space shuttle comprise a major part of the body. -

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Medical Report

NASA SP-411 The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Medical Report National Aeronautics and Space Administration THE APOLLO-SOYUZ TEST PROJECT MEDICAL REPORT , .. Ji I NASA SP-411 The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Medical Report Compiled by Arnauld E. Nicogossian,M.D. 1977 Scientific and Technical Information Office National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC For sale by the National Technical Information Service Springfield, Virginia 22161 Price - $6.00 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Apollo Soyuz Test Project. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project medical report. (NASA SP ; 411) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Space medicine. 2. Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. 3. Space flight-Physiological effect. I. Nicogossian, Arnauld E. II. Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. III. Title. IV. Series: United States. National Aero nautics and Space Administration. NASA SP ; 411. RC1l35.A66 616.9'80214 77-2370 FOREWORD The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) was both an end and a beginning. It was the final flight of the highly successful Apollo program. It was the last time that three U.S. astronauts, tightly packed into a command module, would launch from an expendable booster, elbow their way through space, and then return gracefully to a salty splashdown. But it was the first time that an international purpose to manned flight was demonstrated. Joint docking and the sharing of quarters, experiments, and pro visions have all symbolized the feasibility and the will of cooperative space explora tion. As we summarize the Life Sciences findings of this mission, we look forward to the future. We are confident that international manned missions will continue in ever increasing frequency and duration. -

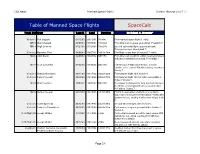

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target.