Nicholas F. Jones the Organization of Corinth Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

(Eponymous) Heroes

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Athenian Political Art from the fi h and fourth centuries: Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes S e Cleisthenic reforms of /, which fi rmly established democracy at Ath- ens, imposed a new division of Attica into ten tribes, each of which consti- tuted a new political and military unit, but included citizens from each of the three geographical regions of Attica – the city, the coast, and the inland. En- rollment in a tribe (according to heredity) was a manda- tory prerequisite for citizenship. As usual in ancient Athenian aff airs, politics and reli- gion came hand in hand and, a er due consultation with Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, each new tribe was assigned to a particular hero a er whom the tribe was named; the ten Amy C. Smith, “Athenian Political Art from the Fi h and Fourth Centuries : Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , A.C. Smith. tribal heroes are thus known as the eponymous (or name giving) heroes. T : Aristotle indicates that each hero already received worship by the time of the Cleisthenic reforms, although little evi- dence as to the nature of the worship of each hero is now known (Aristot. -

A Garrison at Oropos?

A Garrison at Oropos? The primary military function of the Athenian ephebeia in the Lycurgan era (and the likely reason for its existence) was to protect the inhabitants of Attica against small bands of raiders originating from Boeotia. According to the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia “ephebes patrol the countryside and spend time in the guard-posts (phylakteria)” in the second year of their national service (42.4: περιπολοῦσι τὴν χώραν καὶ διατρίβουσιν ἐν τοῖς φυλακτηρίοις). If the ephebeia was created sometime after Alexander of Macedon’s destruction of Thebes in September 335 BCE, it would mean that the terminus post quem for the regular deployment of a minimum of one phyle of ephebes at these phylakteria was 333/2 BCE (Friend 2019). The epigraphic habit of the ephebes who had garrisoned the defensive infrastructure of Attica in the 330s and 320s BCE, until the probable abolition of the ephebeia after the Lamian War, permits the identification of the Athenaion Politeia’s unnamed “guard-posts”. An analysis of those end of service dedications erected by individual ephebic phylai reveals that the phylakteria would have consisted of fortified demes (Eleusis, Rhamnous, and Oinoe) and of border forts (Phyle and Panactum) situated at the Attic-Boeotian frontier or at the northeastern coast of Attica. Did the ephebes also garrison Oropos after the acquisition of the frontier stronghold from Alexander in 335/4 (rather than from Philip in 338/7), just as in the Peloponnesian War (Thuc. 8.60.1)? Two arguments can be adduced in support of the view that ephebes (and presumably their older compatriots) were responsible for patrolling the Oropia. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Roads and Forts in Northwestern Attica Author(S): Eugene Vanderpool Source: California Studies in Classical Antiquity, Vol

Roads and Forts in Northwestern Attica Author(s): Eugene Vanderpool Source: California Studies in Classical Antiquity, Vol. 11 (1978), pp. 227-245 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25010733 . Accessed: 08/12/2014 16:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to California Studies in Classical Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.22.1.233 on Mon, 8 Dec 2014 16:03:34 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EUGENE VANDERPOOL Hp6cKEiTatTij; 3COpacfipCl O6pj esydXa, KaIKcovTa iffi Tiv Botioiav, 6S' )v Eiei TV Xcpav ooao60t Cs vai E KCai IpodavTEtS Xenophon, Memorabilia 3. 5.25 Roads and Forts in Northwestern Attica In recent years I have done a good deal of walking, accompanied by various members of the American School of Classical Studies, in the mountainous country of northwestern Attica between the upland plains of Mazi and Skourta and the coastal plain of Eleusis.' The peaks in this region, which are covered with a forest of pine, rise to heights of over seven hundred meters above sea level, their sides are steep and often precipitous, and they are separated by deep valleys in which flow the two streams, the Kokkini and the Sarandapotamos, which unite to form the Eleusinian Kephissos just before they emerge from the hills into the coastal plain (figs. -

The City of Dionysos: a Social and Historical Study of the Ionian City of Teos

THE CITY OF DIONYSOS: A SOCIAL AND HISTORICAL STUDY OF THE IONIAN CITY OF TEOS by JONATHAN RYAN STRANG February 16th, 2007 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics Committee Members: Dr. Carolyn Higbie (Advisor) Dr. Susan Guettel Cole Dr. Bradley Ault UMI Number: 3268815 UMI Microform 3268815 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Abstract The present study focuses on tying together all the archaeological, architectural, and epigraphic research on the ancient Greek polis of Teos in Ionia. The work falls into two distinct parts. The first section surveys the geography, the political history, and the society and government of Teos. These chapters will draw upon sources from the full history of the ancient city, from its foundation down until the abandonment of the site. The second part comprises of four separate studies. The first of these will deal with the cult of Dionysos at Teos and will examine the mythology, architecture, and cult practices for the god. The inscription recording a pirate attack on Teos will serve as the starting point for a chapter exploring the recurring problem of piracy in the general area of Teos and the social developments that came about because of it. -

The Heroes of Phyle

THE HEROES OF PHYLE Upon these men the crown of valor Was placed by Athens' ancient people; They were the vanguard of those stalwarts Wlho crushed the cruel tyrants' power And lawless rule; nor shunned they peril. Only modest public honors were granted to Thrasyboulos and the small group of patriots who were the first to join him in his fight for the return of freedom and democracy in Athens. He and his friends, while 'living as refugees in Thebes, under- stood the execution of Theramenes as an indication that the rule of the Thirty had turned into a desperate tyranny. These exiles trusted that Attika was full of truly democratic citizens who disapproved of the terror that had swept over their country in consequence of the military defeat of Athens and the subsequent occupation by the army of the enemy. But the desired downfall of these well-established forces required more than disapproval, and Thrasyboulos was determined by a courageous effort to turn this silent hostility into open revolt. He had not trusted in vain either in the democratic spirit of his fellow-citizens or in the hatred aroused by the Thirty against their own rule. And yet the importance of the heroic action of this small group of men must not be underestimated; they turned despair into hope and inertia into courage. It was in the early winter of the year 404/3 B.C. that Thrasyboulos set out from Thebes accompanied by seventy men.' He crossed into Attika and arrived in the mountain deme Phyle, a place that could easily be defended from all sides.2 The news of Thrasyboulos' arrival spread, and, in spite of the military measures taken by the Thirty, his snmallgroup increased daily. -

Spartan Hegemony I, Key Words

Week 12: The Struggle for Hegemony in Fourth-Century Greece Lecture 21, The Spartan Hegemony I, Key Words Thebes Lysander Agis Pausanias Decarchies Harmosts Tribute Asiatic Greeks Samos Law Epitadeus Hypomeiones Cinadon Neodamodeis Perioikoi The Thirty Critias Gorgias Socrates Orator Twenty Theramenes Ten Council of 500 Sycophants Gerousia Homoioi Hoplite Census Thrasybulus Anytus Phyle Lysias Metics 3000 Reign of Terror Niceratus Leon of Salamis 1500 700 Callibius Eleusis Thras Battle of Munychia 1 Amnesty Ten at Piraeus Eleven Nepos Pausanias The Academy Son of Lycus Hermes by Praxiteles 2 Lecture 22, The Spartan Hegemony II, Key Words The Ten Thousand Tissaphernes Thibron Conon Evagoras of Cyprus Pharnabazus Artaxerxes Conon Agesilaus Agamemnon Aulis Boeotian Insult Rhodes Cnidos Corinthian War Corinth Thebes War on Elis Timocrates of Rhodes Tithraustes Argos Phocis Locris Thras Euboea Chalcidice Acarnania Ismenias Heraclea Nemea Isthmus Coronea Iphicrates Peltasts Spartan mora Lemnos Imbros Scyros Delos Chios Argive-Corinthian union Antalchidas Hellespont Clazomenae 3 Cyprus Boeotian League Mantinea Phlius Chalcidian Confederacy Olynthus Apollonia Acanthus Phoebidas Leontiades Cadmea Thesmophoria Pelopidas Epaminondas Sphodrias Second Athenian League Bicameral Synedrion Syntaxis Phoros Cleruchies Byzantium Mytilene Methymna Rhodes Autonomy 4 Chronological Table for the Spartan Hegemony 404-371 405 immediately following his victory at Aegospotami, Lysander, to ensure the destruction of Athens’ empire, takes control of Sestos on the -

The Freedom of the Greeks in the Early Hellenistic Period (337-262 BC)

The Freedom of the Greeks in the Early Hellenistic Period (337-262 BC). A Study in Ruler-City Relations Shane Wallace Ph.D. University of Edinburgh 2011 Signed Declaration This thesis has been composed by the candidate, the work is the candidate‘s own and the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Signed: ii Abstract This thesis treats of the use and meaning of the Greek concept of eleutheria (freedom) and the cognate term autonomia (autonomy) in the early Hellenistic Period (c.337-262 BC) with a specific focus on the role these concepts played in the creation and formalisation of a working relationship between city and king. It consists of six chapters divided equally into three parts with each part exploring one of the three major research questions of this thesis. Part One, Narratives, treats of the continuities and changes within the use and understanding of eleutheria and autonomia from the 5th to the 3rd centuries. Part Two, Analysis, focuses on the use in action of both terms and the role they played in structuring and defining the relationship between city and king. Part Three, Themes, explores the importance of commemoration and memorialisation within the early Hellenistic city, particularly the connection of eleutheria with democratic ideology and the afterlife of the Persian Wars. Underpinning each of these three sections is the argument that eleutheria played numerous, diverse roles within the relationship between city and king. In particular, emphasis is continually placed variously on its lack of definition, inherent ambiguity, and the malleability of its use in action. -

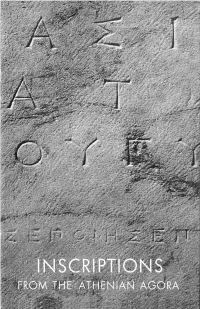

Agorapicbk-10.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 10 Prepared by Benjamin D. Meritt Photographs by Alison Frantz Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut The thirty-five inscriptions shown here represent but a small selec- tion of the many types of written records found in the Athenian Ag- ora. Each of the now over 7000 inventoried stones, of course, carries a unique text, and each is worthy of study in its own right; prelimi- nary publication may be found, for the most part, in the volumes of Hesperia. EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS i. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (igsi) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos 11 in Athens (1959) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (1960) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1960) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (1961) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore $Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfroni the Athenian Agora (1966) 11. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (1971) 13. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (1973) 14. Grazti in the Athenian Agora (1974) 15. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (1976) German and French editions (1977) 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A. -

DEME THEATERS in ATTICA and the TRITTYS SYSTEM Author(S): Jessica Paga Source: Hesperia: the Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol

DEME THEATERS IN ATTICA AND THE TRITTYS SYSTEM Author(s): Jessica Paga Source: Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. 79, No. 3 (July-September 2010), pp. 351-384 Published by: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40981054 . Accessed: 18/03/2014 10:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 71.168.218.10 on Tue, 18 Mar 2014 10:15:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HESPERIA 79 (2010) DEME THEATERS IN Pages 351-384 ATTICA AND THE TRITTY5 SYSTEM ABSTRACT Analysisof the physical form and geographic distribution of deme theaters in Atticademonstrates their multiplicity offunctions during the Classical period. A patternof one théâtral area per trittys per phyle is identified,pointing to the use ofthe trittyes as nodesof communication within the broader framework ofAthenian society and democratic organization. -

Identification of Some Sites in Northwestern Attica

APPENDIX IDENTIFICATION OF SOME SITES IN NORTHWESTERN ATTICA Although the correlation of ancient place names with archaeological sites is not central to the thesis of this study, it is an issue which has ex cited a good deal of scholarly interest and should be considered briefly. The identifications of Phyle (the main fort), Rhamnous, and Eleusis have never been in doubt. The identification of Kotroni as the acropolis of the deme of Aphidna and of Palaiokastro as the site of the Spartan camp at Dekeleia are less certain, but have been accepted by most modern scholars. There is less agreement on the identification of the sites in northwestern Attica. The locations of the district and village of Eleutherai, the deme of Oinoe, the fort of Panakton, and the regions of Drymos and Orgas have been much debated. I propose only to point out the main lines of argumentation. For a full review of the literary evidence and of scholarly opinion, C. N. Edmonson, "The Topography of Northwest Attica" (unpublished Ph.D dissertation, University of California, Berkeley 1966) is indispensable although I do not agree with his identifications for any of the sites considered below. Eleutherai: The district of Eleutherai was on the northwestern border between Plataea and the rest of Attica and was almost certainly the Mazi plain. Pausanias (1.38.8) says that Plataea is presently the border be tween Boeotia and Attica, but that formerly Eleutherai had been the border. Arrian (1. 7 .9) mentions the "gates" (the Kaza pass) that lead from Boeotia to Eleutherai and Attica.