The Forfeiture by Wrongdoing Exception To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights Violations

Civil Rights Violations Police Misconduct Nicholas S. Kamau, Esq. Police Misconduct Any improper or illegal behavior engaged in by a police officer while attempting to administer justice Types of Police Misconduct Excessive Force – The use of force that exceeds the amount of force that a police officer reasonably believes is necessary. Whether the amount of force was objectively reasonable under the circumstances is a factual issue to be determined by the jury. Types of Police Misconduct Sexual Misconduct- Sexual misconduct includes sexual harassment or sexual assault, indecent assault, an act of indecency, possession of child pornography or other behaviors of a sexual nature which are crimes in Pennsylvania. Sexual misconduct is the second most reported form of police misconduct. Types of Police Misconduct Witness Tampering –This behavior concerns an officer who attempts to either change a witness’ testimony, or prevents a witness from testifying in a criminal or civil proceeding. Types of Police Misconduct False confessions – Some officers convince individuals to give false confessions, convincing them to plead guilty to something they did not actually do. Types of Police Misconduct Racial profiling – Racial profiling is the use of someone’s race or ethnicity as a justification for suspecting him of committing a crime. For instance, assuming a man must be a terrorist because he’s Muslim, or assuming a black man driving an expensive car must have stolen it. Types of Police Misconduct False Arrest - A false arrest is an arrest that is made without a warrant, or without probable cause. A person may sue on the grounds of false arrest if there was not a legitimate reason to arrest him in the first place. -

Threats and Consent

Wrongs and Crimes Chapter 11 Threats and Consent Note: This is a draft chapter from a long book on criminalization entitled Wrongs and Crimes that I am in the process of completing. It is one of four chapters on consent. I hope that it is reasonably self-standing (though, obviously, all apparent egregious errors are shown to be brilliant insights in other parts of the book). Victor Tadros Threats and deception can undermine valid consent. When do they do so? Why do they do so? What affects the gravity of the resultant wrongdoing? And when should the conduct that the victim does not consent to be criminalized as a result? Although these questions are general I will explore them in the important and difficult realm of wrongful penetrative sex. This chapter is concerned with threats, the next with deception. Work on sexual wrongdoing generates sharp disagreement, not only about what we should think, but also about how we should think about it. Some are hostile to the use of my standard philosophical method in this context, especially the use of unusual hypothetical cases. Using this method, some think, trivializes sexual wrongdoing, or fails to show respect to victims of wrongdoing. In employing this method, I aim at a clearer and deeper grasp of sexual wrongdoing. As we will see, the nature and scope of sexual wrongdoing is by no means obvious. We owe it to victims and potential victims of sexual wrongdoing to use the tools that are best suited to develop a clear and deep grasp of that wrongdoing. -

Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions for the District Courts of the First Circuit)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE 2019 REVISIONS TO PATTERN CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE DISTRICT COURTS OF THE FIRST CIRCUIT DISTRICT OF MAINE INTERNET SITE EDITION Updated 6/24/19 by Chief District Judge Nancy Torresen PATTERN CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT Preface to 1998 Edition Citations to Other Pattern Instructions How to Use the Pattern Instructions Part 1—Preliminary Instructions 1.01 Duties of the Jury 1.02 Nature of Indictment; Presumption of Innocence 1.03 Previous Trial 1.04 Preliminary Statement of Elements of Crime 1.05 Evidence; Objections; Rulings; Bench Conferences 1.06 Credibility of Witnesses 1.07 Conduct of the Jury 1.08 Notetaking 1.09 Outline of the Trial Part 2—Instructions Concerning Certain Matters of Evidence 2.01 Stipulations 2.02 Judicial Notice 2.03 Impeachment by Prior Inconsistent Statement 2.04 Impeachment of Witness Testimony by Prior Conviction 2.05 Impeachment of Defendant's Testimony by Prior Conviction 2.06 Evidence of Defendant's Prior Similar Acts 2.07 Weighing the Testimony of an Expert Witness 2.08 Caution as to Cooperating Witness/Accomplice/Paid Informant 2.09 Use of Tapes and Transcripts 2.10 Flight After Accusation/Consciousness of Guilt 2.11 Statements by Defendant 2.12 Missing Witness 2.13 Spoliation 2.14 Witness (Not the Defendant) Who Takes the Fifth Amendment 2.15 Definition of “Knowingly” 2.16 “Willful Blindness” As a Way of Satisfying “Knowingly” 2.17 Definition of “Willfully” 2.18 Taking a View 2.19 Character Evidence 2.20 Testimony by Defendant -

Sagicor Fraud & Other Wrongdoing Policy

SAGICOR FRAUD & OTHER WRONGDOING POLICY September 2008 i Sagicor Fraud and Other Wrongdoing Policy TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ………………………….……………….……………………………… 1 2 Scope of Policy ………………………………………………...…..……………..... 1 3 Definitions and Actions That May Constitute Fraud ……………..……………... 1 4 Other Inappropriate or Wrongful Conduct ……………………………………….. 2 5 Related Policies……………………………………………………………………… 2 6 Confidentiality……………...………………...………………...………………...….. 2 7 Whistleblower Protection..…….……………...………………...………………...... 3 8 Responsibilities……………………………………………………………...………. 3 8.1 Management ………………………...…………………..……………… 3 8.2 Employees …………………………….....……………...…………..….. 3 8.3 Enterprise Risk Management …………………………………...…..… 4 8.4 Internal Audit……………………......……….………………………..…. 4 8.5 Legal Department ………………………………………………………. 4 8.6 Audit Committee and Board of Directors……………………………... 4 8.7 Various Departments …..……………...………………...………….…. 4 8.8 Investigation Unit ……………..……………..……………...…….……. 4 8.9 Investigation Team…..…………...………………...………………...… 5 9 Security of Evidence ………………...……………...………………...…………… 5 10 Authorization for Investigating Suspected Fraud or other Wrongdoing ….…… 5 11 Reporting Procedures……………...………………...………………...…………… 5 11.3 Employees ……………………………………..……………......………. 5 11.4 Managers ………………………………………………………………… 6 11.5 Company Compliance Officers ………………………………………... 6 11.6 Anonymous Reports …………………………..……………...………… 6 11.7 Investigation Inquiries…………………………………………………… 6 12 Termination ………………………………………………………………………….. 6 13 Administration ………………………………………………………………………. -

Working with the Justice Sector to End Violence Against Women and Girls

Working with the Justice Sector to End Violence against Women and Girls Developed by: Cheryl Thomas, Director, Women’s Program Laura Young, Staff Attorney, International Justice Program Mary Ellingen, Staff Attorney, Women’s Program Contributors: Margarita Alarcon, Lawyer (Cuba) Dr. Kelly Askin, Senior Legal Officer, International Justice, Open Society Justice Initiative, United States Lisa Dailey, Lawyer (United States) Geraldine R. Bjallerstedt, Lawyer, Head of Nairobi Office, Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (Kenya) Terence Fitzgerald, Senior Program Specialist, Justice Operations Division, International Justice Mission (United States) Loretta Frederick, Senior Legal and Policy Advisor, Battered Women’s Justice Project, (Minnesota, United States) Albena Koycheva, Lawyer (Bulgaria) Audrey Lee and Ann Campbell, International Women’s Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific (Malaysia) Sara A. Lulo, Executive Director, Avon Global Center for Justice, Adjunct Professor of Law, Cornell Law School (United States) Patricia MacIntosh, Deputy Minister of Community Services (Canada) Aileen Marques, Lawyer (India) Eniko Pap, Lawyer (Hungary) Dr. Maria F. Perez Solla, Lawyer (Austria) Justice Sonia A.C. Rivera, Senior Judge, Gender Violence Specialized Court (Madrid, Spain) Dr. Anicée Van Engeland-Nourai, Lecturer in Law, University of Exeter, Research Associate, SOAS (United Kingdom) Joan Winship, Executive Director, International Association of Women Judges (United States) Justice Sector Module 1 December 2011 INTRODUCTION -

PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the THIRD CIRCUIT ___No. 10-2790 ___UNITED STATES of AMERI

PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT _____________ No. 10-2790 _____________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. GLORIOUS SHAVERS, a/k/a G, a/k/a G-Bucks, a/k/a Julious Colzie, a/k/a Glorious Grand Glorious Shavers, Appellant _____________ No. 10-2931 _____________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JERMEL LEWIS, a/k/a STAR, a/k/a PR-STAR, a/k/a P Jermel Lewis, Appellant _____________ No. 10-2971 _____________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. ANDREW WHITE, Appellant _________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (Crim. Nos. 08-01616-001, 08-0161-002, 08-0161-003) District Judge: Honorable J. Curtis Joyner Argued March 19, 2012 _________________ Before: RENDELL, FISHER, and CHAGARES, Circuit Judges. (Filed: August 27, 2012) 2 Keith M. Donoghue, Esq. (Argued) Robert Epstein, Esq. Kai N. Scott, Esq. Federal Community Defender Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania 601 Walnut Street The Curtis Center, Suite 540 West Philadelphia, PA 19106 Attorneys for Appellant Glorious Shavers Paul J. Hetznecker, Esq. (Argued) Suite 911 1420 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 Attorney for Appellant Jermel Lewis Carina Laguzzi, Esq. Laguzzi & Associates 1500 John F. Kennedy Boulevard Suite 200 Philadelphia, PA 19102 Attorney for Appellant Andrew White Robert A. Zauzmer, Esq. (Argued) Arlene D. Fisk, Esq. Office of United States Attorney 615 Chestnut Street Suite 1250 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Attorneys for Appellee 3 __________________ OPINION __________________ CHAGARES, Circuit Judge. This is a consolidated appeal by three codefendants, Glorious Shavers, Andrew White, and Jermel Lewis (collectively referred to as the “appellants”), who were convicted of robbery affecting interstate commerce, conspiracy to commit robbery affecting interstate commerce, witness tampering, and using and carrying firearms during and in relation to a crime of violence. -

STATE V. ORTIZ—CONCURRENCE BISHOP, J., Concurring in Part and Concurring in the Judgment

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** STATE v. ORTIZÐCONCURRENCE BISHOP, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment. I believe that the evidence at trial was suffi- cient to convict the defendant, Akov Ortiz, of tampering with a witness in violation of General Statutes § 53a- 151 (a), not for the reasons stated by the majority, but because the trial evidence permitted the jury reasonably to infer, from the defendant's threatening behavior toward the victim, that he intended to prevent the victim from testifying at trial. -

Ground Lost and Found in Criminal Discovery Roger J

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Published Scholarship The onorH able Roger J. Traynor Collection 1964 Ground Lost and Found in Criminal Discovery Roger J. Traynor Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/traynor_scholarship_pub Recommended Citation Roger J. Traynor, Ground Lost and Found in Criminal Discovery , 39 N.Y.U. L. REV. 228 (1964). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/traynor_scholarship_pub/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The onorH able Roger J. Traynor Collection at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Published Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7c Ti, L GROUND LOST AND FOUND IN CRIMINAL DISCOVERY ROGER J. TRAYNOR Reprinted from New York University Law Review April 1964, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 228-250 New York University School of Law Arthur T. Vanderbilt Hall 40 Washington Square South New York, N. Y. 10003 Q Copyright, 1964, by New York University GROUND LOST AND FOUND IN CRIMINAL DISCOVERY ROGER J. TRAYNOR system is that it elicits a reasonable T HEapproximation plea for the ofadversary the truth. The reasoning is that with each side on its mettle to present its own case and to challenge its op- ponent's, the relevant unprivileged evidence in the main emerges in the ensuing clash. Such reasoning is hardly realistic unless the evidence is accessible in advance to the adversaries so that each can prepare accordingly in the light of such evidence. -

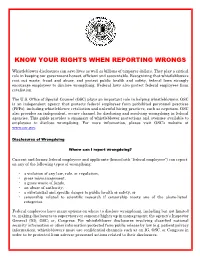

Know Your Rights When Reporting Wrongs

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS WHEN REPORTING WRONGS Whistleblower disclosures can save lives as well as billions of taxpayer dollars. They play a critical role in keeping our government honest, efficient and accountable. Recognizing that whistleblowers root out waste, fraud and abuse, and protect public health and safety, federal laws strongly encourage employees to disclose wrongdoing. Federal laws also protect federal employees from retaliation. The U.S. Office of Special Counsel (OSC) plays an important role in helping whistleblowers. OSC is an independent agency that protects federal employees from prohibited personnel practices (PPPs), including whistleblower retaliation and unlawful hiring practices, such as nepotism. OSC also provides an independent, secure channel for disclosing and resolving wrongdoing in federal agencies. This guide provides a summary of whistleblower protections and avenues available to employees to disclose wrongdoing. For more information, please visit OSC’s website at www.osc.gov. Disclosures of Wrongdoing Where can I report wrongdoing? Current and former federal employees and applicants (henceforth “federal employees”) can report on any of the following types of wrongdoing: • a violation of any law, rule, or regulation, • gross mismanagement, • a gross waste of funds, • an abuse of authority, • a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety, or • censorship related to scientific research if censorship meets one of the above-listed categories. Federal employees have many options on where to disclose wrongdoing, including but not limited to, making disclosures to supervisors or someone higher up in management; the agency’s Inspector General (IG); OSC; or, Congress. For whistleblower disclosures involving classified national security information or other information protected from public release by law (e.g. -

Admissions of Guilt in Civil Enforcement Verity Winship

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 2018 Admissions of Guilt in Civil Enforcement Verity Winship Jennifer K. Robbennolt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Winship, Verity and Robbennolt, Jennifer K., "Admissions of Guilt in Civil Enforcement" (2018). Minnesota Law Review. 100. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/100 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Admissions of Guilt in Civil Enforcement Verity Winship† & Jennifer K. Robbennolt†† Introduction ............................................................................. 1078 I. The Context of Civil Enforcement ................................... 1083 A. Agency Enforcement ................................................... 1083 B. The Role of Settlement ............................................... 1088 C. Consequences of Admissions Policy .......................... 1091 II. Admission Models ............................................................. 1095 A. No Admission .............................................................. 1096 1. Factual Allegations .............................................. 1097 2. Denial .................................................................... 1100 3. No Denial -

Kant's Typo, and the Limits of the Law

Kant's Typo, and the Limits of the Law The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Newhouse, Marie E. 2013. Kant's Typo, and the Limits of the Law. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11158257 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Kant’s Typo, and the Limits of the Law A dissertation presented by Marie E. Newhouse to The Committee on Higher Degrees in Public Policy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Public Policy Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 i © 2013 Marie E. Newhouse All rights reserved. ii Advisor: Professor Arthur Applbaum Marie E. Newhouse Kant’s Typo, and the Limits of the Law Abstract This dissertation develops a Kantian philosophical framework for understanding our individual obligations under public law. Because we have a right to do anything that is not wrong, the best interpretation of Immanuel Kant’s Universal Principle of Right tracks the two ways—material and formal—in which actions can be wrong. This interpretation yields surprising insights, most notably a novel formulation of Kant’s standard for formal wrongdoing. Because the wrong-making property of a formally wrong action does not depend on whether or not the action in question has been prohibited by statute, Kant’s legal philosophy is consistent with a natural law theory of public crime. -

Witness Tampering Is Against the Law!

WITNESS TAMPERING IS AGAINST THE LAW THE DEFENDANT SHOULD NEVER THREATEN OR BRIBE YOU! If someone is trying to stop you from going to court or telling the truth in court you can get help with a SAFETY PLAN: WITNESS The ASU Diane Halle Center for Family Justice TAMPERING IS (602) 258-1656 It is against the law for the defendant AGAINST THE to offer a bribe to a victim or witness. Phoenix Family Advocacy Center (602) 534-2120 or (888) 246-0303 LAW! What is a bribe? Under the law a bribe is a promise of Voice for Victims “any benefit” to a witness to stay (480) 600-2661 or (602) 416-6780 quiet, lie, or not show up in court. The Arizona Coalition Against Domestic Violence Examples: (602) 279-2900 or (800) 782-6400 Each of the following statements could be a bribe: “If you testify . Maricopa County Attorney’s Office “I will stop beating you.” Investigations Division (602) 506-8370 “I will pay the rent.” If someone bribes you or “I will buy you a car." Remember… threatens to stop you from “I will buy the kids presents.” If you need immediate help or if you are in an emergency, testifying in court, you may be a victim of “witness tampering.” call 9-1-1 right away! *Witness tampering is the most common crime committed KNOW THE LAW ON against abuse victims. *Please share widely* WITNESS TAMPERING *Help us stop it! The ASU Diane Halle Center for Family Justice By Hannah Burnidge, 3L & Prof. Sarah Buel with thanks to the many who gave suggestions.