Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to <I>Lyrical

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-15-2014 Revising for Genre: Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to Lyrical Tales Shelley AJ Jones University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, S. A.(2014). Revising for Genre: Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to Lyrical Tales. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3008 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVISING FOR GENRE: MARY ROBINSON’S POETRY FROM NEWSPAPER VERSE TO LYRICAL TALES by Shelley AJ Jones Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2002 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2004 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Anthony Jarrells, Major Professor William Rivers, Committee Member Christy Friend, Committee Member Amy Lehman, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Shelley AJ Jones, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION For my boys. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project, like Robinson’s poetry, has benefited from the many versions it has taken. While many friends and colleagues, and my dissertation committee in its current composition, have been kind enough to offer guidance on my work over the years, I would like to acknowledge specifically Paula Feldman’s contribution as the former director of the dissertation committee. -

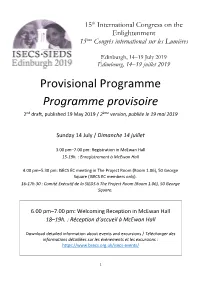

Programme19may.Pdf

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

Prints Collection

Prints Collection: An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Prints Collection Title: Prints Collection Dates: 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825) Extent: 54 document boxes, 7 oversize boxes (33.38 linear feet) Abstract: The collection consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. RLIN Record #: TXRC02-A1 Language: English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Provenance The Prints Collection was assembled by Theater Arts staff, primarily from the Messmore Kendall Collection which was acquired in 1958. Other sources were the Robert Downing and Albert Davis collections. Processed by Helen Baer and Antonio Alfau, 2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Prints Collection Scope and Contents The Prints Collection, 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825), consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. The collection is organized in three series: I. Individuals, 1669-1906 (58.25 boxes), II. Theatrical Prints, 1720-1891 (1.75 boxes), and III. Works of Art and Miscellany, 1827-82 (1 box), each arranged alphabetically by name or subject. The prints found in this collection were made by numerous processes and include lithographs, woodcuts, etchings, mezzotints, process prints, and line blocks; a small number of prints are hand-tinted. A number of the prints were cut out from books and periodicals such as The Illustrated London News, The Universal Magazine, La belle assemblée, Bell's British Theatre, and The Theatrical Inquisitor; others comprised sets of plates of dramatic figures such as those published by John Tallis and George Gebbie, or by the toy theater publishers Orlando Hodgson and William West. -

British Humour Satirical Prints of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

British Humour Satirical Prints of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Comics and caricatures were born in eighteenth-century Europe. While the Enlightenment8 gave rise to a culture of criticism, the bolder art of ridicule can be credited to innovative artists responding to great social changes of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This exhibition focuses on three generations of British satirists pioneering this new form: William Hogarth, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, and George Cruikshank. Hogarth, the “grandfather of the political cartoon,” lampooned the mores and behaviors of the ruling class, but no class, station, or profession was above his reproach. Following his example, Gillray and Rowlandson became thorns in the sides of aristocratic and public leaders by styling a new form of caricature with exaggerated features and proportions. Cruikshank, from a family of satirists, was able to imitate the style of Gillray so closely that Gillray’s publisher, Hannah Humphrey, hired him to complete projects the older artist left unfinished, and he was hailed in his lifetime as a “Modern Hogarth.” But comedy is serious business, because it speaks truth to power. These artists were at turns threatened, bullied, and bribed; they became part of the very debates they depicted and derided. Each succeeded because they created and then fulfilled the demands of a highly engaged citizenry, which is part of any democratic society valuing freedom of debate and expression. Modern counterparts, from editorial cartoons to The Daily Show, continue their tradition. William Hogarth (British, 1697–1764) The complete series Marriage à la Mode, 1745 Etching and engraving on paper Prints made by Gérard Jean-Baptiste Scotin II Gift of Museum Associates (2008.16.1-6) Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode was his first series of satirical images that focused on elite British society. -

House of Lords Library: Gillray Collection

Library: Special Collections House of Lords Library: Gillray Collection The House of Lords Library Gillray collection was acquired in 1899 as a bequest from Sir William Augustus Fraser (1826–1898). The collection consists of eleven folio volumes, retaining Fraser’s fine bindings: half red morocco with elaborate gold tooling on the spines. Ownership bookplates on the verso of the front boards show Fraser’s coat of arms and some of the prints bear his “cinquefoil in sunburst” collector’s mark. The volumes are made up of leaves of blue paper, on to which the prints are pasted. Perhaps surprisingly, given the age of the paper and adhesive, there is no evident damage to the prints. Due to the prints being stored within volumes, light damage has been minimised and the colour is still very vibrant. The collection includes a few caricatures by other artists (such as Thomas Rowlandson) but the majority are by Gillray. It is possible that the prints by other artists were mistakenly attributed to Gillray by Fraser. Where Fraser lacked a particular print he pasted a marker at the relevant chronological point in the volume, noting the work he still sought. These markers have been retained in the collection and are listed in the Catalogue. The collection includes some early states of prints, such as Britania in French Stays and a few prints that are not held in the British Museum’s extensive collection. For example, Grattan Addresses the Mob is listed in Dorothy George’s Catalogue as part of the House of Lords Library’s collection only.1 Volume I includes a mezzotint portrait of the author by Charles Turner, and two manuscript letters written by Gillray; one undated and addressed to the artist Benjamin West; the other dated 1797 and addressed to the publisher John Wright. -

Tfs 2.4 2016

VOL.2 No .4, 2016 The Future of INSIDE THIS ISSUE The Life of Mrs Gooch**** Chawton House Library What women writers wouldn’t say Chawton at Washington Our account of the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM FTER MORE THAN 20 YEARS AS Sandy has generously pledged to cover the costs of running the Library until the end of 2017, and to gift THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF a final lump sum to contribute towards the annual Seduction and Celebrity TRUSTEES, DR SANDY LERNER HAS A running costs thereafter. Her intention is that we What Mary Robinson is doing ANNOUNCED THAT SHE IS STEPPING DOWN should use her generous support as a ‘challenge’ in Greenwich FROM THE BOARD, AND TAKING ON THE gift to raise matched funding to secure the future HONORARY POSITION OF FOUNDING PATRON. of the Library. Sandy Lerner is a highly successful, innovative, Dr Linda Bree, of Cambridge University Press, our and original entrepreneur. Her career highlights interim Chair, writes: include co-founding Cisco Systems and starting the cosmetics company, Urban Decay, as well as ‘What Sandy Lerner has done in establishing Chawton more recent involvement in ethical and sustainable House Library is a magnificent thing, and what she farming, in accordance with her strong interest in animal welfare. Sandy has been honoured by many proposes – as she turns her attention, after all this time, universities and organisations around the world for to her other interests – is typically generous. We will now her extraordinary philanthropy. In May 2015, she need to work towards a sustainable future for the Library was presented with an honorary OBE for services which will pay tribute to her vision, and the years of to UK culture. -

Open Showalter Sensational Lives Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DIVISION OF ENGLISH SENSATIONAL LIVES: BYRON AND ROBINSON‘S LIVES MIRRORED IN LITERATURE ADRIENNE SHOWALTER Fall 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Arnold A. Markley Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Adam J. Sorkin Distinguished Professor of English Honors Advisor *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College i ABSTRACT Sensational Lives: Byron and Robinson‘s Lives Mirrored in Literature This paper analyzes the lives and selected works of two controversial British Romantic writers: Mary Darby Robinson and Lord Byron. Both writers‘ lives and work were in the public eye in a manner more reminiscent of modern celebrity culture. Due to their celebrity, both authors‘ made use of their personal lives to enhance their written works. In some cases, they used their poems or novels as a way to manipulate or otherwise control their public persona. This thesis attempts to ascertain the level of personal experience apparent in the author‘s works through research of biographies and memoirs, critical texts, and explications of the subjects‘ literary material. The works examined include Mary Darby Robinson‘s ―The Linnet‘s Petition‖ and The Natural Daughter and Lord Byron‘s Don Juan and The Bride of Abydos. Keywords: Byron, Robinson, celebrity, persona, feminism, sexuality ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................i -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Aesthetic Intersections

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Aesthetic Intersections: Portraiture and British Women’s Life Writing in the Long Eighteenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Flavia Ruzi September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Adriana Craciun, Chairperson Dr. George Haggerty Dr. Malcolm Baker Copyright by Flavia Ruzi 2017 ii The Dissertation of Flavia Ruzi is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside iii Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support of my committee, who have stood relentlessly beside me through every step of the process. I am immensely grateful to Adriana Craciun for her continued faith in my project and in my capacity to meet her ambitious expectations. She has made me a better writer and a more sophisticated thinker. I would also like to express my gratitude to Malcolm Baker, who has patiently born with my literary propensities through my examination of art historical materials. His dedicated guidance has enabled me to discuss such materials in each chapter with the art historical rigor they deserve. The interdisciplinary impetus of my project would not have been possible without him. And I would like to thank George Haggerty, who has been there for me since the first day of my graduate career and continues to inspire me with his unabating love for eighteenth- century literature. The reading group he organized for me and my friend, Rebecca Addicks-Salerno, was instrumental in the evolution of my project. Our invaluable conversations ensured that my dissertation was not a lonely and isolated process but the product of an eighteenth-century-salon-like culture of enjoyable intellectual exchange. -

British Art Studies November 2016 British Art Studies Issue 4, Published 28 November 2016

British Art Studies November 2016 British Art Studies Issue 4, published 28 November 2016 Cover image: Martin Parr, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, East Sussex, England, UK, 1978. Digital image courtesy of Martin Parr / © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos (LON28062) PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Super-size caricature: Thomas Rowlandson's Place des Victoires at the Society of Artists in 1783, Kate Grandjouan Super-size caricature: Thomas Rowlandson's Place des Victoires at the Society of Artists in 1783 Kate Grandjouan Abstract This article re-examines an ambitious caricature of the French that Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) exhibited in London in 1783. -

Saplings Cover

Face to Face AUTUMN/WINTER 2011 My Favourite Portrait by Erin O’Connor The First Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2011 Comedians: From the 1940s to Now COVER DETAIL AND BELOW Frances Abington as Prue in Love for Love by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1771 © Yale Center for British Art. Paul Mellon Collection This portrait will feature in the exhibition The First Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons from 20 October 2011 until 8 January 2012 in the Wolfson Gallery Face to Face Issue 37 Communications & Development Director and Deputy Director Pim Baxter Communications Officer Helen Corcoran Editor Elisabeth Ingles Designer Annabel Dalziel All images National Portrait Gallery, London and © National Portrait Gallery, London, unless stated www.npg.org.uk Recorded Information Line 020 7312 2463 FROM THE DIRECTOR THIS OCTOBER the Gallery presents The First we preview Scott of the Antarctic, a select Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons, the display of rarely seen photographs of the ill- first exhibition to explore art and theatre in fated expedition. Arriving at the Gallery after eighteenth-century England through portraiture. a national tour, Comedians: From the 1940s A major exhibition featuring portraits of to Now will be on show from September; learn actresses such as Nell Gwyn, Elizabeth Farren, more about this photographic display, and its Lavinia Fenton and Sarah Siddons by artists origins, on pages 14–15. 2011 marks the third including Reynolds, Gainsborough, Hogarth year of Chasing Mirrors, a partnership project and Gillray, it will include major loans from between the National Portrait Gallery and other museums, alongside works from private young people involved with community collections on show to the public for the first organisations in Brent, Barnet and Ealing, time. -

Download Full Book

Staging Governance O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Staging Governance: Theatrical Imperialism in London, 1770–1800. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60320. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60320 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 18:04 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Staging Governance This page intentionally left blank Staging Governance theatrical imperialism in london, 1770–1800 Daniel O’Quinn the johns hopkins university press Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Karl and Edith Pribram Endowment. © 2005 the johns hopkins university press All rights reserved. Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Staging governance : theatrical imperialism in London, 1770–1800 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8018-7961-2 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. English drama—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Theater—England— London—History—18th century. 5. Political plays, English—History and criticism. 6. Theater—Political aspects—England—London. 7. Colonies in literature. I. Title. PR719.I45O59 2005 822′.609358—dc22 2004026032 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY A Catalogue of Various Prints adapted for furniture, ornaments, etc. published by R. Ackermann, at his Repository of Arts, No. 101, Strand (London: Rudolph Ackermann, 1802) A catalogue of various Prints, Medallions, Transparencies, and Caricatures, adapted for Furniture, Ornaments, & Amusement; also a great variety of drawing books and rudiments, consisting of about 2000 plates, published by R. Ackermann, at his Repository of Arts, No 101 Strand, London (London: Rudolph Ackermann, 1805) A List of the Livery of London, alphabetically arranged under their several Wards, districts, and other places of residence. In 30 parts (London, 1802) Ackermann’s New Drawing Book, Comprising Groups of Figures, Cattle, and other Animals, for the Embellishment of Landscapes, Designed and Engraved by J. F. Manskirsh (London: Rudolph Ackermann, 1808) Catalogue général des livres composant les bibliothèques du Département de la marine et des colonies (Paris, 1838) Catalogue of Atlas’s, Maps, Prints, Books of Penmanship, and Miscellaneous Works, excepting sea-charts and hydrographic publications (London: Laurie & Whittle, 1813) Catalogue of Materials for water-colour painting, and sketching, pencil, and chalk drawing (London: Windsor & Newton, 1849) Catalogue. Ackermann publisher of Books and Prints, and superfine water colour manufacturer to his Majesty (London: Rudolph Ackermann, 1830) Chesterfield Travestie; or, School for Modern Manners. Embellished with Ten Caricatures, Engraved by Woodward from original Drawings by Rowlandson (London: Printed by Thomas Plummer, Seething-Lane, for Thomas Tegg, 111, Cheapside 1808) © The Author(s) 2017 197 J. Baker, The Business of Satirical Prints in Late-Georgian England, Palgrave Studies in the History of the Media, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-49989-5 198 BIBLIOGRAPHY Chronology, or the Historians Companion; being an authentic register of events, from the earliest period to the present time, comprehending an epitome of universal his- tory, with a copious list of the most eminent men in all ages of the world.