Century England by Kellye Corcoran a Disserta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in the Work of Colley Cibber

BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS HUMANISTIC STUDIES Vol. 1 October 1, 1912 No. 1 STUDIES IN THE WORK OF COLLEY CIBBER BY DE WITT C.:'CROISSANT, PH.D. A ssistant Professor of English Language in the University of Kansas LAWRENCE, OCTOBER. 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS I Notes on Cibber's Plays II Cibber and the Development of Sentimental Comedy Bibliography PREFACE The following studies are extracts from a longer paper on the life and work of Cibber. No extended investigation concerning the life or the literary activity of Cibber has recently appeared, and certain misconceptions concerning his personal character, as well as his importance in the development of English literature and the literary merit of his plays, have been becoming more and more firmly fixed in the minds of students. Cibber was neither so much of a fool nor so great a knave as is generally supposed. The estimate and the judgment of two of his contemporaries, Pope and Dennis, have been far too widely accepted. The only one of the above topics that this paper deals with, otherwise than incidentally, is his place in the development of a literary mode. While Cibber was the most prominent and influential of the innovators among the writers of comedy of his time, he was not the only one who indicated the change toward sentimental comedy in his work. This subject, too, needs fuller investigation. I hope, at some future time, to continue my studies in this field. This work was suggested as a subject for a doctor's thesis, by Professor John Matthews Manly, while I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago a number of years ago, and was con• tinued later under the direction of Professor Thomas Marc Par- rott at Princeton. -

Her Hour Upon the Stage: a Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1965 Her Hour Upon the Stage: A Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress Julie Ann Farrer Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Farrer, Julie Ann, "Her Hour Upon the Stage: A Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress" (1965). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2862. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2862 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HER HOUR UPON THE STAGE: A STUDY OF ANNE BRAC EGIRDLE, RESTORATION ACTRESS by Julie Ann Farrer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis, in its final form, owes much to a number of willing people, without whose help the entire undertaking would be incomplete or else impossible. First thanks must go to Dr. Robert C. Steensma, chairman of my committee, and an invaluable source of help and encour agement throughout the entire year. I am also indebted to the members of my committee, Dr. Del Rae Christiansen and Dr. King Hendricks for valid and helpful suggestions . Appreciation is extended to Utah State University, to the English department and to Dr. Hendricks . I thank my understanding parents for making it possible and my friends for ma~ing it worthwhile . -

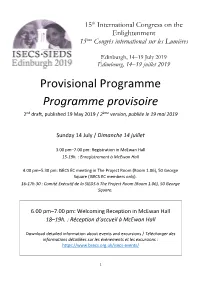

Programme19may.Pdf

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

Prints Collection

Prints Collection: An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Prints Collection Title: Prints Collection Dates: 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825) Extent: 54 document boxes, 7 oversize boxes (33.38 linear feet) Abstract: The collection consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. RLIN Record #: TXRC02-A1 Language: English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Provenance The Prints Collection was assembled by Theater Arts staff, primarily from the Messmore Kendall Collection which was acquired in 1958. Other sources were the Robert Downing and Albert Davis collections. Processed by Helen Baer and Antonio Alfau, 2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Prints Collection Scope and Contents The Prints Collection, 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825), consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. The collection is organized in three series: I. Individuals, 1669-1906 (58.25 boxes), II. Theatrical Prints, 1720-1891 (1.75 boxes), and III. Works of Art and Miscellany, 1827-82 (1 box), each arranged alphabetically by name or subject. The prints found in this collection were made by numerous processes and include lithographs, woodcuts, etchings, mezzotints, process prints, and line blocks; a small number of prints are hand-tinted. A number of the prints were cut out from books and periodicals such as The Illustrated London News, The Universal Magazine, La belle assemblée, Bell's British Theatre, and The Theatrical Inquisitor; others comprised sets of plates of dramatic figures such as those published by John Tallis and George Gebbie, or by the toy theater publishers Orlando Hodgson and William West. -

Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson

Please do not remove this page Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage: Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson Ledoux, Ellen Malenas https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643459340004646?l#13643538220004646 Ledoux, E. M. (2014). Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage: Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson. In Stage Mothers: Women, Work, and the Theater, 1660-1830 (pp. 79–101). Rowman & Littlefield. https://doi.org/10.7282/T38G8PKB This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/28 21:58:31 -0400 Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson Ellen Malenas Ledoux 1 March 2013 A smooth black band drawn over an impossibly white neck, a luminous bust barely concealed under fashionable dishabillé, powdered locks set off by a black hat profuse with feathers--these focal points, and many others, are common to two of the Romantic-era’s most famous celebrity portraits: Sir Joshua Reynolds’s “Mrs. Mary Robinson” (1782) and Thomas Gainsborough’s “Sarah Siddons” (1785). (See figure 1.) Despite both drawing on modish iconography in their choice of composition, pose, and costume, Reynolds and Gainsborough manage to create disparate tones. Siddons awes as a noble matron, whereas Robinson oozes sexuality with a “come hither” stare. The paintings’ contrasting tones reflect and promulgate the popular perceptions of these two Romantic-era actresses from the playhouse and the media. In the early 1780s Siddons was routinely referred to as a “queen” or a “goddess,” whereas Robinson was unceremoniously maligned by her detractors as a “whore.”1 Current scholarship on Siddons and Robinson devotes considerable attention to how these women’s semi-private sexual lives had major influence over their respective characterizations. -

William Congreve University Archives

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange The John C. Hodges Collection of William Congreve University Archives Spring 1970 The John C. Hodges Collection of William Congreve Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_libarccong Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation "The John C. Hodges Collection of William Congreve" (1970). The John C. Hodges Collection of William Congreve. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_libarccong/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The John C. Hodges Collection of William Congreve by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES Occasional Publication NU:MBER 1 • SPRING 1970 The Occasional Publication of The University of Tennessee Libraries is intended to be very flexible in its content and in its frequency of publication. As a medium for descriptive works re lated to various facets of library collections as well as for contributions of merit on a variety of topics, it will not be limited in format or subject matter, nor will it be issued at prescribed intervals' JOHN DOBSON, EDITOR JOHN C. HODGES 1892-1967 THE JOHN C. HODGES COLLECTION OF William Congreve In The University of Tennessee Library: A Bibliographical Catalog. Compiled by ALBERT M. LYLES and JOHN DOBSON KNOXVILLE· THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES· 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 73-631247 Copyright © 1970 by The University of Tennessee Libraries, Knoxville, Tennessee. -

Saplings Cover

Face to Face AUTUMN/WINTER 2011 My Favourite Portrait by Erin O’Connor The First Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2011 Comedians: From the 1940s to Now COVER DETAIL AND BELOW Frances Abington as Prue in Love for Love by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1771 © Yale Center for British Art. Paul Mellon Collection This portrait will feature in the exhibition The First Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons from 20 October 2011 until 8 January 2012 in the Wolfson Gallery Face to Face Issue 37 Communications & Development Director and Deputy Director Pim Baxter Communications Officer Helen Corcoran Editor Elisabeth Ingles Designer Annabel Dalziel All images National Portrait Gallery, London and © National Portrait Gallery, London, unless stated www.npg.org.uk Recorded Information Line 020 7312 2463 FROM THE DIRECTOR THIS OCTOBER the Gallery presents The First we preview Scott of the Antarctic, a select Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons, the display of rarely seen photographs of the ill- first exhibition to explore art and theatre in fated expedition. Arriving at the Gallery after eighteenth-century England through portraiture. a national tour, Comedians: From the 1940s A major exhibition featuring portraits of to Now will be on show from September; learn actresses such as Nell Gwyn, Elizabeth Farren, more about this photographic display, and its Lavinia Fenton and Sarah Siddons by artists origins, on pages 14–15. 2011 marks the third including Reynolds, Gainsborough, Hogarth year of Chasing Mirrors, a partnership project and Gillray, it will include major loans from between the National Portrait Gallery and other museums, alongside works from private young people involved with community collections on show to the public for the first organisations in Brent, Barnet and Ealing, time. -

Download Full Book

Staging Governance O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Staging Governance: Theatrical Imperialism in London, 1770–1800. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60320. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60320 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 18:04 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Staging Governance This page intentionally left blank Staging Governance theatrical imperialism in london, 1770–1800 Daniel O’Quinn the johns hopkins university press Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Karl and Edith Pribram Endowment. © 2005 the johns hopkins university press All rights reserved. Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Staging governance : theatrical imperialism in London, 1770–1800 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8018-7961-2 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. English drama—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Theater—England— London—History—18th century. 5. Political plays, English—History and criticism. 6. Theater—Political aspects—England—London. 7. Colonies in literature. I. Title. PR719.I45O59 2005 822′.609358—dc22 2004026032 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

"Great Writers." EDITED by PROFESSOR ERIC S

"Great Writers." EDITED BY PROFESSOR ERIC S. ROBERTSON, M.A. LIFE OF CONGREVE. LIFE OF WILLIAM CONGREVE BY EDMUND GOSSE, M.A. CLARK LECTURER IN ENGLISH LITERATURE AT TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE LONDON WALTER SCOTT, 24 WARWICK LANE NEW YORK : THOMAS WHITTAKER TORONTO : W. J. GAGE & CO. 1888 (All rights reserved.) h CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE The Congreve family; William Congreve born at Bardsey, February 10, 1670; removal to Youghal and Lismorej goes to Kilkenny, 1681, and to Trinity College, Dublin, 1685 ; begins to write at college; friendship with Swift; returns to England, 1688 ; writes Incognita, not published until February 25, 1692 ; account of that novel; The Old Bachelor composed in a country garden, 1690; entered at the Middle Temple, March 17, 1691 ; the life in London coffee-houses ; introduced to Dryden ; the Juvenal and Persius published October 27, 1692; forms the friendship of Southerne, Hopkins, Maynwaring, Moyle, and other men of letters; The Old Bachelor accepted at the Theatre Royal, and produced, January, 1693, with very great suc cess ; characteristics of this comedy; anecdote of Purcell and Dennis^ 13 CHAPTER II. Congreve's success; friendship with Montague; The Double Dealer produced in November, 1693 5 characteristics of that play; Dryden's eulogy on it; Swift's epistle to the 6 CONTENTS. author ; Queen Mary's patronage of Congreve ; introduc tion to Addison; theatrical intrigues in London, and foundation of the Lincoln's Inn Theatre; Congreve pub lishes The Mourning Muse of Alexis, January 28, 1695 ; Love for Love produced at Easter, 1695; characteristics and history of that comedy; Dennis publishes Letters upon Several Occasions, containing Congreve's essay on Humour in Comedy, dated July 10, 1695 ; Congreve is made a commissioner of hackney coaches; he publishes the Ode to the King; produces The Mourning Bride early in 1697 5 characteristics and history of that tragedy ; Congreve pub lishes The Birth of the Muse, Nov. -

John Collet (Ca

JOHN COLLET (CA. 1725-1780) A COMMERCIAL COMIC ARTIST TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I CAITLIN BLACKWELL PhD University of York Department of History of Art December 2013 ii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the comic work of the English painter John Collet (ca. 1725- 1780), who flourished between 1760 and 1780, producing mostly mild social satires and humorous genre subjects. In his own lifetime, Collet was a celebrated painter, who was frequently described as the ‘second Hogarth.’ His works were known to a wide audience; he regularly participated in London’s public exhibitions, and more than eighty comic prints were made after his oil paintings and watercolour designs. Despite his popularity and prolific output, however, Collet has been largely neglected by modern scholars. When he is acknowledged, it is generally in the context of broader studies on graphic satire, consequently confusing his true profession as a painter and eliding his contribution to London’s nascent exhibition culture. This study aims to rescue Collet from obscurity through in-depth analysis of his mostly unfamiliar works, while also offering some explanation for his exclusion from the British art historical canon. His work will be located within both the arena of public exhibitions and the print market, and thus, for the first time, equal attention will be paid to the extant paintings, as well as the reproductive prints. The thesis will be organised into a succession of close readings of Collet’s work, with each chapter focusing on a few representative examples of a significant strand of imagery. These images will be examined from art-historical and socio-historical perspectives, thereby demonstrating the artist’s engagement with both established pictorial traditions, and ephemeral and topical social preoccupations. -

Performance of the Self in the Theatre of the Elite the King's Theatre, 1760

Performance of the self in the theatre of the elite The King’s Theatre, 1760–1789: The opera house as a political and social nexus for women. Joanna Jarvis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Design and Media This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/?ref=chooser-v1 October 2019 Volumes 1 & 2 0 1 Abstract This research takes as its starting point the King’s Theatre in London, known as the Opera House, between 1760 and 1789. It examines the elite women subscribers who were on display and their approach to self-presentation in this social and political nexus. It makes a close examination of four women who sat in the audience at that time, as exemplars of the various experiences and approaches to attending the opera. Recent research has examined the performative offerings at the Opera House, the constitution of the audience and the troubled management of the theatre in that period. What is missing, is an examination of the power of the visual in confirming and maintaining status. As a group the women presented a united front as members of the ruling class, but as individuals they were under observation, as much from their peers as others in the audience and the visual dynamic of this display has not been analysed before. The research uses a combination of methodological approaches from a range of disciplines, including history, psychology and phenomenology, in order to extrapolate a sense of the experience for these women. -

Pregnancy and Performance on the British Stage in the Long Eighteenth Century, 1689-1807

“Carrying All Before Her:” Pregnancy and Performance on the British Stage in the Long Eighteenth Century, 1689-1807 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chelsea Phillips, MFA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Lesley Ferris, Advisor; Dr. Jennifer Schlueter; Dr. Stratos Constantinidis; Dr. David Brewer Copyright by Chelsea Lenn Phillips 2015 ABSTRACT Though bracketed by centuries of greater social restrictions, the long eighteenth century stands as a moment in time when women enjoyed a considerable measure of agency and social acceptance during pregnancy. In part, this social acceptance rose along with birth rates: the average woman living in the eighteenth century gave birth to between four and eight children in her lifetime. As women spent more of their adult lives pregnant, and as childbearing came to be considered less in the light of ritual and more in the light of natural phenomenon, social acceptance of pregnant women and their bodies increased. In this same century, an important shift was occurring in the professional British theatre. The eighteenth century saw a rise in the respectability of acting as a profession generally, and of the celebrity stage actress in particular. Respectability does not mean passivity, however—theatre historian Robert Hume describes the history of commercial theatre in eighteenth century London as a “vivid story of ongoing competition, sometimes fierce, even destructive competition.”1 Theatrical managers deployed their most popular performers and entertainments strategically, altering the company’s repertory to take advantage of popular trends, illness or scandal in their competition, or to capitalize on rivalries.