Performance of the Self in the Theatre of the Elite the King's Theatre, 1760

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Dancer Taking Leap Into World of Professional Ballet Vancouver Native Eyeing the Crown at International Contest

Young dancer taking leap into world of professional ballet Vancouver native eyeing the crown at international contest Vancouver native Derek Drilon, currently between gigs with the Joffrey and Boston Ballet companies, will dance with his home school, Northwest Classical Ballet, on June 18. (Courtesy of Northwest Classical Ballet) By Scott Hewitt, Columbian Arts & Features Reporter Published: June 10, 2016, 6:04 AM It’s good to be the prince. “I like playing princely roles. It feels pretty natural to me,” said Derek Drilon, 19. That makes sense. At age 19, the Vancouver native recently assumed a position of young royalty in the largest international dance competition in the world. The Youth America Grand Prix draws thousands of aspiring ballet dancers to regional semi- final competitions in cities all over the world, where professional judges evaluate each dancer’s performance, potential and artistry. Finalists are invited to New York City for the final contest, with prizes of scholarship money to the world’s leading dance academies and the invaluable contacts and connections that follow. Drilon won the semi-final Grand Prix Award in Chicago and was named one of the top six men in the New York finals, for his performance of the Siegfried Variation from “Swan Lake.” In Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Prince Siegfried is enraptured with a woman who has been transformed into a swan — but then falls under the spell of a pretender, with tragic consequences. The prince’s famously expressive solo dance, as he considers his predicament and his passion, require great power and artistry. Comedy is a whole different challenge. -

Introduction: the Royal Character in the Public Imagination 1

Notes Introduction: The Royal Character in the Public Imagination 1. I use the words “royal” and “monarch” (and their variants, “royalty,” “monarchy,” “monarchical,” etc.) interchangeably. By the late eigh- teenth century both terms in common usage referred equally to kings and to those who ruled (queens, regents). “Royal” also referred, and still does, to near relatives of the monarch, as in “royal family,” and I use it in this sense also. 2. Austen’s conservatism is famously unstable. Feminist critics espe- cially have suggested that a feminist subtext undercuts or at least tempers the conservative trajectories of her novels. In Equivocal Beings, Claudia Johnson provides a comprehensive discussion of the conservative reading of Emma as well as its implicit feminist critique (192–96). 3. Unlike Pride and Prejudice, in which she was revising an earlier draft, Austen wrote Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion after 1810. She began writing Mansfield Park in February 1811, the same month in which the Regency began (Sturrock 30; see also Tomalin 223–24). 4. Clara Tuite suggests that Mansfield Park can be read as “a provincial deflection of the wider national issues of responsible hereditary gov- ernment” (Romantic Austen 132). 5. The phrase “Queen Caroline affair” historically refers to the events of 1820 and 1821, when the uncrowned King attempted to divorce his wife by Act of Parliament. Although Caroline was technically Queen, supporters of the new King used a variety of means, some political, some rhetorical, to contest her legitimacy. Similarities as well as an evident continuity between this episode and the Prince’s first attempt to obtain a divorce, some fifteen years earlier, have often led scholars to refer to their marital disputes before, during, and after the Regency as the Queen Caroline affair. -

'Henley' Fits Perfectly in Turf Trinity

THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2019 ‘HENLEY’ FITS PERFECTLY BROMANS TO OFFER A DOZEN YEARLINGS AT SARATOGA IN CHANGE OF TACTICS IN TURF TRINITY by Christie DeBernardis Chester and Mary Broman have dedicated 22 years to the New York breeding program and have enjoyed quite a bit of success with the likes of GI Breeders’ Cup F/M Sprint winner Bar of Gold (Medaglia d’Oro), MGISW Artemis Agrotera (Roman Ruler) and GI Florida Derby hero Friends Lake (A.P. Indy), among others. The couple spent the first 20 years racing everything they produced on their 300-acre farm in Chestertown, N.Y., but starting last term, they began selling off their crops in what Chester Broman refers to as estate planning. Buyers at Fasig- Tipton’s upcoming yearling sales will have a chance to acquire some of New York’s finest with five Broman-bred yearlings in the Saratoga Selected Yearling Sale and an additional seven in the NY-Bred Yearling Sale. Cont. p5 Henley’s Joy | Sarah Andrew IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Joe Bianca TOO DARN HOT ADDS SUSSEX TO RESUME SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY--Back when the New York Racing Too Darn Hot (GB) (Dubawi {Ire}) made it two Group 1 victories Association announced its bold new initiative for 3-year-old turf on the bounce, taking the G1 Qatar Sussex S. at Goodwood on horses in the summer, a trio of big-money events dubbed the Wednesday after winning the G1 Prix Jean Prat on July 7. Click “Turf Trinity,” many quipped that it would quickly be or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. -

November Ebn Mon

WEDNESDAY, 7TH OCTOBER 2020 ALL EYES ON KEENELAND NOVEMBER EBN MON. 9 - WED. 18 EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU TODAY’S HEADLINES TATTERSALLS EBN Sales Talk Click here to is brought to contact IRT, or you by IRT visit www.irt.com PANTILE’S BEAUTY SNAPPED UP BY BAHRAIN Bahrain’s intent as a growing power within European racing was clearly signalled when Book 1 of the Tattersalls October Yearling Sunday’s Gr.1 Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe is won by Sottsass Sale opened in Newmarket yesterday, writes Carl Evans. (Siyouni), who has been retired to join the stallion roster Operating for a member of the Gulf state’s royal family, at Coolmore. See story on page 17. bloodstock agent Oliver St Lawrence was underbidder on a 2,000,000gns half-sister to Golden Horn and then secured the session’s top lot, a son of Kingman (Lot 174), whose sale for 2,700,000gns was a windfall of epic size for breeder Colin Murfitt. IN TODAY’S ISSUE... It was also the best ring result for consignor Robin Sharp of Houghton Bloodstock, whose previous auction high was one of Steve Cargill’s Racing Week p20 500,000gns. Racing Round-up p21 The jewel which generated such a sum is a half-brother to the Gr.1 2,000 Guineas winner and sire Galileo Gold, who was First Crop Sire Maidens p26 produced by the Galileo mare Galicuix. She was bought by Pinhooking Tables p28 Murfitt for 8,000gns at the 2013 December Sale, having earlier See pages 3 & 5 – October Yearlings -

SOH-Annual-Report-2016-2017.Pdf

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2016-17 Contents Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2016-17 01 About Us Our History 05 Who We Are 08 Vision, Mission and Values 12 Highlights 14 Awards 20 Chairman’s Message 22 CEO’s Message 26 02 The Year’s Activity Experiences 37 Performing Arts 37 Visitor Experience 64 Partners and Supporters 69 The Building 73 Building Renewal 73 Other Projects 76 Team and Culture 78 Renewal – Engagement with First Nations People, Arts and Culture 78 – Access 81 – Sustainability 82 People and Capability 85 – Staf and Brand 85 – Digital Transformation 88 – Digital Reach and Revenue 91 Safety, Security and Risk 92 – Safety, Health and Wellbeing 92 – Security and Risk 92 Organisation Chart 94 Executive Team 95 Corporate Governance 100 03 Financials and Reporting Financial Overview 111 Sydney Opera House Financial Statements 118 Sydney Opera House Trust Staf Agency Financial Statements 186 Government Reporting 221 04 Acknowledgements and Contact Our Donors 267 Contact Information 276 Trademarks 279 Index 280 Our Partners 282 03 About Us 01 Our History Stage 1 Renewal works begin in the Joan 2017 Sutherland Theatre, with $70 million of building projects to replace critical end-of-life theatre systems and improve conditions for audiences, artists and staf. Badu Gili, a daily celebration of First Nations culture and history, is launched, projecting the work of fve eminent First Nations artists from across Australia and the Torres Strait on to the Bennelong sail. Launch of fourth Reconciliation Action Plan and third Environmental Sustainability Plan. The Vehicle Access and Pedestrian Safety 2016 project, the biggest construction project undertaken since the Opera House opened, is completed; the new underground loading dock enables the Forecourt to become largely vehicle-free. -

Bay Filly (IRE) – February 4Th, 2008

BAY FILLY (GB) March 24th, 2016 Danehill Danehill Dancer Mira Adonde Mastercraftsman (IRE) Black Tie Affair Starlight Dreams Reves Celestes Night Shift Azamour Asmara Porttraitoflove (IRE) (2009) Green Desert Flashing Green Colorsnap MASTERCRAFTSMAN (IRE), Grey or Roan horse, 2006, by Danehill Dancer (IRE), out of Starlight Dreams (USA), by Black Tie Affair. Champion 2yr old in Europe in 2008. Won 7 races, value £1,018,611, at 2 and 3, from 6 furlongs to 1 mile 2½ furlongs, Bank of Scotland (Ire) National Stakes, Curragh, Gr.1, Ind. Waterford Wedgwood Phoenix Stakes, Curragh, Gr.1, St James's Palace Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, boylesports.com Irish 2000 Guineas, Curragh, Gr.1, One 51 Railway Stakes, Curragh, Gr.2, Diamond Stakes, Dundalk, Gr.3, also placed second in Juddmonte International Stakes, York, Gr.1, and third in Tatts Millions Irish Champion Stakes, Leopardstown, Gr.1. Retired to Stud in 2010, and sire of the winners of 613 races, and £14,620,389; including THEE AULD FLOOZIE (NZ) (Spinning World (USA), Harcourts Thorndon Mile, Gr.1), VALLEY GIRL (NZ) (Bianconi (USA), Herbie Dyke Stakes, Gr.1), AMAZING MARIA (IRE) (Tale of The Cat (USA), Falmouth Stakes, Gr.1, Prix Rothschild, Gr.1), KINGSTON HILL (GB) (Rainbow Quest (USA), Ladbrokes St Leger Stakes, Gr.1, Racing Post Trophy, Gr.1), THE GREY GATSBY (IRE) (Entrepreneur (GB), QIPCO Irish Champion Stakes, Gr.1, Prix du Jockey Club, Gr.1), MIME (NZ) (Montjeu (IRE), Travis Dulcie Stakes, Gr.2, Cambridge Stud Sir Tristram Classic (f), Gr.2), EVEN SONG (IRE) (Sadler's Wells (USA), Ribblesdale -

Programme19may.Pdf

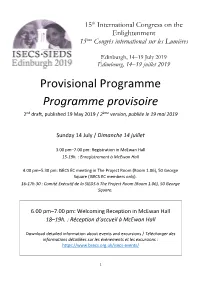

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

Prints Collection

Prints Collection: An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Prints Collection Title: Prints Collection Dates: 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825) Extent: 54 document boxes, 7 oversize boxes (33.38 linear feet) Abstract: The collection consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. RLIN Record #: TXRC02-A1 Language: English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Provenance The Prints Collection was assembled by Theater Arts staff, primarily from the Messmore Kendall Collection which was acquired in 1958. Other sources were the Robert Downing and Albert Davis collections. Processed by Helen Baer and Antonio Alfau, 2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Prints Collection Scope and Contents The Prints Collection, 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825), consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. The collection is organized in three series: I. Individuals, 1669-1906 (58.25 boxes), II. Theatrical Prints, 1720-1891 (1.75 boxes), and III. Works of Art and Miscellany, 1827-82 (1 box), each arranged alphabetically by name or subject. The prints found in this collection were made by numerous processes and include lithographs, woodcuts, etchings, mezzotints, process prints, and line blocks; a small number of prints are hand-tinted. A number of the prints were cut out from books and periodicals such as The Illustrated London News, The Universal Magazine, La belle assemblée, Bell's British Theatre, and The Theatrical Inquisitor; others comprised sets of plates of dramatic figures such as those published by John Tallis and George Gebbie, or by the toy theater publishers Orlando Hodgson and William West. -

Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson

Please do not remove this page Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage: Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson Ledoux, Ellen Malenas https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643459340004646?l#13643538220004646 Ledoux, E. M. (2014). Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage: Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson. In Stage Mothers: Women, Work, and the Theater, 1660-1830 (pp. 79–101). Rowman & Littlefield. https://doi.org/10.7282/T38G8PKB This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/28 21:58:31 -0400 Working Mothers on the Romantic Stage Sarah Siddons and Mary Robinson Ellen Malenas Ledoux 1 March 2013 A smooth black band drawn over an impossibly white neck, a luminous bust barely concealed under fashionable dishabillé, powdered locks set off by a black hat profuse with feathers--these focal points, and many others, are common to two of the Romantic-era’s most famous celebrity portraits: Sir Joshua Reynolds’s “Mrs. Mary Robinson” (1782) and Thomas Gainsborough’s “Sarah Siddons” (1785). (See figure 1.) Despite both drawing on modish iconography in their choice of composition, pose, and costume, Reynolds and Gainsborough manage to create disparate tones. Siddons awes as a noble matron, whereas Robinson oozes sexuality with a “come hither” stare. The paintings’ contrasting tones reflect and promulgate the popular perceptions of these two Romantic-era actresses from the playhouse and the media. In the early 1780s Siddons was routinely referred to as a “queen” or a “goddess,” whereas Robinson was unceremoniously maligned by her detractors as a “whore.”1 Current scholarship on Siddons and Robinson devotes considerable attention to how these women’s semi-private sexual lives had major influence over their respective characterizations. -

Notes Upon Dancing Historical and Practical by C. Blasis

: / NOTES UPON DANCING, HISTORICAL AND PRACTICAL, BY C. BLASIS, BALLET MASTER TO THE ROYAL ITALIAN OPERA, COVENT GARDEN ; FINISHING MASTER OF THE IMPERIAL ACADEMY OF DANCING AT MILAN; AUTHOR OF A TREATISE ON DANCING, AND OTHER WORKS ON THEATRICAL ART, PUBLISHED IN ITALY, FRANCE, AND ENGLAND. FOLLOWED BY A HISTORY OF THE IMPERIAL AND ROYAL ACADEMY OF DANCING, AT MILAN, TO WHICH ARE ADDED BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICES OF THE BLASIS FAMILY, INTERSPERSED WITH VARIOUS PASSAGES ON THEATRICAL ART. EDITED AND TRANSLATED, FROM THE ORIGINAL FRENCH AND ITALIAN, by R. BARTON. WITH ENGRAVINGS. ? - 4 . / E r -7 ' • . r ' lionJjon PUBLISHED BY M. DELAPORTE, 116, REGENT STREET, AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. 1847. Digitized by Google M'OOWAN AND CO., GREAT WINDMILL STREET, HAYMAREET Digitized by Google Digitized by Google ; ADVERTISEMENT. (by tiik kditor.) It will be seen, that the principle object of this work is to place that part of the entertainment at the Lyric Theatres or Opera, called the Ballet, on a new basis. This, the eminent artiste, who is the author of this work, has already effected in his own country, where he is patronized and supported by the government, and is there undoubtedly the first in his profession, as he is perhaps in Europe. The true object of the Ballet appears to be the Beautiful in motion, supported by expressive and well-adapted music. This may be effected in two ways, by two classes of movements the one is quick, vehement and joyous, and is no other than Dancing—but the other class of motions is a far different tiling ; it is no less than a mute expression of feelings, passions, ideas, intentions, or any other sensations belonging to a reasonable being—this is properly termed Pantomime, and must also be sus- tained by music, which now becomes a kind of explanatory voice ; and while it greatly assists the Mime, when well adapted to the subject to be ex- pressed by his gestures, it produces upon the mind and feelings of the spectator an extraordinary effect. -

Cal Poly Arts Brings Miami City Ballet to PAC Oct. 5 for Performance of "Coppelia"

California Polytechnic State University Sept. 17, 2004 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: LISA WOSKE (805) 756-7110 Cal Poly Arts Brings Miami City Ballet To PAC Oct. 5 For Performance of "Coppelia" SAN LUIS OBISPO – The light-hearted tale of star-crossed lovers and mistaken identities is exquisitely danced in “Coppelia,” the full-length comic ballet performed by Miami City Ballet on Tuesday, October 5, 2004 at the Christopher Cohan Center. Part of the Cal Poly Arts Great Performances Series, the 19th Century, Romantic era masterpiece of comedy is presented at a special 7 p.m. curtain time. “Coppelia” takes place in three acts and tells the story of two mischievous lovers who, on the eve of their nuptials, find their affection for each other surprisingly put to the test. The beloved classical ballet was first presented by the Paris Opera Ballet on May 2, 1870. The Miami City Ballet production captures the timeless beauty and sweet sensibilities of the classic story. The New Yorker magazine called Miami City Ballet “one of the most daring and rewarding of the younger companies now on the rise.” Founding Miami City Ballet Artistic Director Edward Villella was the first American-born male principal ballet stars of the New York City Ballet (1957-1975). His career is said to have established the male's role in classical dance in the U.S. Villella's vision and style for the Company is based on the neoclassical 20th-century aesthetic established by famed choreographer George Balanchine. The Company’s repertoire features 90 ballets -- including 38 world premieres -- ranging from Balanchine masterworks to pieces by contemporary choreographers such as Paul Taylor. -

Columbus Native Turned Company Dancer Duane Gosa to Perform with Les Ballets Trockadero De Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre February 28

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 18, 2017 Columbus Native Turned Company Dancer Duane Gosa to Perform with Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre February 28 The world’s foremost all-male comic ballet company, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo was founded in 1974 by a group of ballet enthusiasts for the purpose of presenting a playful, entertaining view of traditional, classical ballet in parody form and “en travesti” (males performing female roles). The Trocks, as they are affectionately known, blend their comic approach with a loving knowledge of dance, proving once and for all that men can, indeed, dance “en pointe” without falling flat on their faces. Columbus native Duane Gosa, a member of the company since 2003, will be performing as Helen Highwaters as well as the Legupski Brothers. CAPA presents Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre (39 E. State St.) on Tuesday, February 28, at 7:30 pm. Tickets are $20-$40 at the CAPA Ticket Center (39 E. State St.), all Ticketmaster outlets, and www.ticketmaster.com. To purchase tickets by phone, please call (614) 469-0939 or (800) 745-3000. Founded in 1974 by a group of ballet enthusiasts for the purpose of presenting a playful, entertaining view of traditional, classical ballet in parody form and en travesti, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo first performed in the late-late shows of Off-Off Broadway lofts. The Trocks, as the dancers are affectionately known, quickly garnered a major critical essay by Arlene Croce in The New Yorker which, combined with reviews in The New York Times and The Village Voice, established the company as an artistic and popular success.