Fit-For-Purpose Seed Supply Systems for the Implementation of Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

Prosopis Juliflora Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Prosopis juliflora Prosopis juliflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Fabales Fabaceae Common name ironwood (English), algarrobo (Spanish), Mesquitebaum (German), mesquite (English), bayarone (French), algarroba (Spanish), cují negro (Spanish) Synonym Similar species Summary view this species on IUCN Red List Management Info Preventative measures: A Risk assessment of Prosopis spp. for Australia was prepared by Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER) using the Australian risk assessment system (Pheloung, 1995). The result is a score of 20 and a recommendation of: reject the plant for import (Australia) or species likely to be a pest (Pacific). The Best Practice Manual Mesquite Control and management options for mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in Australia aims to provide the most current information on mesquite in Australia. The control and management options presented in this manual are the combined results of years of trials carried out by many dedicated researchers, landholders, herbicide companies, government officers, landcare groups and others. As mesquite species respond differently to control methods, the most effective method or combination of methods will vary depending on the size, density and species of mesquite present. The manual includes a 'mesquite control tool box'. Included also are a number of case studies to demonstrate best practice. Principal source: Compiler: IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) Updates with support from the Overseas -

Prosopis Pallida) and Implications for Peruvian Dry Forest Conservation

Revista de Ciencias Ambientales (Trop J Environ Sci). (Enero-Junio, 2018). EISSN: 2215-3896. Vol 52(1): 49-70. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rca.52-1.3 URL: www.revistas.una.ac.cr/ambientales EMAIL: [email protected] Community Use and Knowledge of Algarrobo (Prosopis pallida) and Implications for Peruvian Dry Forest Conservation Uso y conocimiento comunitario del algarrobo (Prosopis pallida) e implicaciones para la conservación del bosque seco peruano Johanna Depenthala and Laura S. Meitzner Yoderb a Master’s candidate in Environmental Management with a concentration in Ecosystem Science and Conservation at Duke University; ORCID: 0000-0003-4560-0862, [email protected] b Doctorate in Forestry and Environmental Studies; researcher and professor at Wheaton College, IL, [email protected] Director y Editor: Dr. Sergio A. Molina-Murillo Consejo Editorial: Dra. Mónica Araya, Costa Rica Limpia, Costa Rica Dr. Gerardo Ávalos-Rodríguez. SFS y UCR, USA y Costa Rica Dr. Manuel Guariguata. CIFOR-Perú Dr. Luko Hilje, CATIE, Costa Rica Dr. Arturo Sánchez Azofeifa. Universidad de Alberta-Canadá Asistente: Sharon Rodríguez-Brenes Editorial: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (EUNA) Los artículos publicados se distribuye bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) basada en una obra en http://www. revistas.una.ac.cr/ambientales., lo que implica la posibilidad de que los lectores puedan de forma gratuita descargar, almacenar, copiar y distribuir la versión final aprobada y publicada del artículo, siempre y cuando se mencione la fuente y autoría de la obra. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales (Trop J Environ Sci). -

The Good, the Bad and the Thorny: Impacts of Prosopis in Africa

The Good, the Bad and the Thorny: Impacts of Prosopis in Africa Nick Pasiecznik CAB International, Wallingford, OXON, UK. E-mail: [email protected] April 2004 Tropical agroforesters have been successful over the past 25 years in the selection, introduction, promotion and plantation of many exotic, fast-growing tree species for the benefit of rural people. However, some of these ‘miracle trees’ have proved to be very well adapted to local conditions, escaping from cultivation and spreading widely as aggressive weeds, threatening, rather than improving livelihoods. The status of exotic Prosopis species in sub-Saharan Africa epitomises this dilemma; it is the main plantation species in Cape Verde, the subject of national eradication and control programmes in South Africa, and all possible combinations in between, throughout the Sahel, East and southern Africa. Even after decades of work with probably the most common and widespread, multi-purpose trees in Africa, it appears that the agroforestry research and development community still cannot decide what to advise. Perceptions of Prosopis species vary widely, ranging from the most useful and productive tree tolerant of sites where little else will grow, to a weedy invader worthy only of wholesale eradication. What is a weed to one farmer may be a source of livelihood to another, but the extent of this dichotomy of opinion regarding Prosopis sends a very confused message to extension workers, foresters and farmers, who don’t know whether to plant it, prune it or pull it up. Prosopis trees provided many valuable resources to indigenous populations in the native range, and are still a source of food, feed, fuel, timber and other raw materials today; often the cornerstone of local economies in arid regions where they constitute the main forest resource. -

Production and Characterisation of Prosopis Seed Galactomannan

Research Collection Doctoral Thesis Production and characterisation of Prosopis seed galactomannan Author(s): Cruz Alcedo, Gastón Eduardo Publication Date: 1999 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-003838586 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Diss.ETHNo. 13153 Production and characterisation of Prosopis seed galactomannan A dissertation submitted to the SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ZURICH For the degree of Doctor of Technical Sciences presented by Gaston Eduardo CRUZ ALCEDO Ingeniero Industrial, Universidad de Piura born June 2, 1963 citizen of Peru accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Renato Amadö, examiner Prof. Dr. Felix Escher, co-examiner Ms. Eva Arrigoni, co-examiner Zurich 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Prof. Dr. Renato Amadö, my thesis director, for giving me the opportunity to work in his laboratory, for the fruitful discussions and his excellent guidance. Already in 1987 he believed in my skills and enthusiasm for the study of Prosopis fruits and permitted me to learn many analytical techniques during a stay at the ETH in Zurich. I am happy for winning his estimation. A special thanks is due also to Evi Arrigoni for her practical advice in the laboratory and for her friendly collaboration, as well as for the critical review and correction of my thesis. I am very grateful to her for agreeing to be my co-examiner. I would also like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Felix Escher for agreeing to be co- examiner and for the helpful discussion on processing technologies and the rheology of gums. -

Working Guide for Integrated Management of Invasive Species in the Arid and Semi-Arid Zones of Ethiopia

Working Guide for Integrated Management of Invasive Species in the Arid and Semi-Arid Zones of Ethiopia Photo by: J.Duraisamy @ www.ecoport.org Compiled by: Faith Ryan, USDA Forest Service June, 2011 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Section 1: People and Capacity Building .............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Community Participation ........................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Invasive Species Inventory Tools ................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Information and Coordination Tools ........................................................................................... 5 1.4 Value of Monitoring and Evaluation ........................................................................................... 7 Section 2: Practices and Potential Actions ........................................................................................... 8 2.1 Prevention ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Early Detection / Rapid Response ............................................................................................... 9 2.3 Contain and Control ............................................................................................................... -

General News

Biocontrol News and Information 27(1), 1N–26N pestscience.com General News The Dilemma of Prosopis: Is There a Rose The last article, from South Africa, evaluates the Between the Thorns? status of Prosopis in that country and the conflicts of interest it has created. It addresses many of the The genus Prosopis contains species with outstand- questions raised in the articles above, discussing ingly useful qualities: they grow in arid and semi- from South Africa’s position of experience the limita- arid zones and give high yields where little else will tions of and possibilities for both utilization and grow. They produce high-quality wood for fuel and control, including biological control – also consid- timber, seeds with varied uses as human and animal ering in this context its obligations as part of the food, and other non-wood products. Species from the African continental community. New World have been introduced into Africa, Asia and Australia over the last 200 years. In some coun- These articles are followed by a tribute to Daniel tries, however, introduced Prosopis has become a Gandolfo, who died in January 2006. He worked on highly invasive weed, covering large tracts of land many weed projects for different cooperators, but his with impenetrable thorny thickets and rendering it inputs into Prosopis biocontrol research will be with unusable. It can even be invasive in its area of origin us forever as a result of the fact that David Kissinger in the New World. As affected countries devote named the seed-feeding weevil on which Daniel worked (see South African article, below) Coelo- increasing amounts of time and money to controlling cephalapion gandolfoi. -

Session 3-Grados

New Approaches to Industrialization of Algarrobo (Prosopis pallida) Pods in Peru Nora Grados and Gastón Cruz University of Piura Faculty of Engineering - Laboratory of Chemistry Aptdo. 353, Piura, Peru e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Peruvian "algarrobo" (Prosopis pallida and Prosopis juliflora) and its fruits are described and some new ways for its industrialization are suggested on the basis of the research done at the University of Piura since 1984. The processing alternatives of Prosopis pods developed at the University of Piura are focused especially on the different uses for each part of the fruit [exocarp, mesocarp (pulp), endocarp], and the episperm, endos- perm and cotyledon from the seed. Each of these components has specific industrial applications. Several specific components have been determined. Sucrose is the main sugar (46% in weight) in the pulp. In the endosperm the polysaccharide is a galactomannan, with a 1:1.36 galactose/mannose ratio. Among the important amino acids in the seed cotyledon are: glutamic acid, arginine, aspartic acid, leucine, proline and serine. In the pulp, vitamin C, nicotinic acid, and calcium pantothenate have also been found. In the seed the content of vitamin C and E are significant. The dietary fiber of the pulp and endocarp hulls is basically insoluble dietary fiber. The results of the research show the feasibility of industrialization of Prosopis in Peru. The basic equipment for a pilot plant is being installed at the University of Piura to demonstrate this fact. Introduction Piura is on the northwestern coast of Peru (Figure 1), an arid zone where the annual rainfall is below 100 mm. -

Leguminosae Mesquite

Prosopis spp. Family: Leguminosae Mesquite North American species Prosopis glandulosa-Algaroba, bilayati kikar, common mesquite, cuji, honey locust, honey mesquite, honey-pod, ibapiguazu, inesquirte, ironwood, mesquite, screwbean, Torrey mesquite, wawahi, western honey mesquite. Prosopis pubescens-Mescrew, screwbean, screwbean mesquite, screw-pod mesquite, scrub mesquite, tornillo. Prosopis velutina-Mesquite, velvet mesquite. South/Central American species Prosopis abbreviata-Algarrobillo espinoso. Prosopis alba Acacia de catarina, algaroba, algaroba blanca, algarobo, algarroba, algarrobe blanco, algarrobo, algarrobo bianco, algarrobo blanco, algarrobo impanta, algarrobo panta, aroma, barbasco, bate caixa, bayahonda, carbon, chachaca, cuji yaque, ibope-para, igope, igope-para, ironwood, jacaranda, manca-caballa, mesquite, nacasol, screwbean, tintatico, visna, vit algarroba, white algaroba. Prosopis affinis-Algarobilla, algarobillo, algarrobilla, algarrobo nandubay, algarrobo negro, calden, espinillo, espinillo nandubay, ibope-moroti, nandubay. Prosopis articulata-Mesquit, mesquite, mesquite amargo. Prosopis caldenia-Calden. Prosopis calingastana-Cusqui. Prosopis chilensis-Algaroba chilena. algaroba du chili, algarroba, algarrobo, algarrobo blanco, algarrobo cileno, algarrobo de chile, algarrobo panta, arbol blanco, chilean algaroba, chileens algaroba, cupesi, dicidivi, divi-divi, mesquite, nacascal, nacascol, nacascolote, nasascalote, tcako, trupillo. Prosopis cineraria-Jambu, kandi, shami. Prosopis ferox-Churqui, churqui blanco, churqui -

Usaid/Peru 118/119 Tropical Forest and Biodiversity Analysis

DIEGO PÉREZ USAID/PERU 118/119 TROPICAL FOREST AND BIODIVERSITY ANALYSIS Report authors: Juan Carlos Riveros, Maina Martir-Torres, César Ipenza, Patricia Tello September, 2019 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID/PERU 118/119 TROPICAL FOREST AND BIODIVERSITY ANALYSIS September, 2019 Prepared with technical support from US Forest Service International Programs LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF MAPS Figure 1 Map 1 Summary of Main Threats and Drivers of Official Ecosystems Map of Peru 32 Biodiversity and Tropical Forest Loss in Tropical Forests and Marine Ecosystems 13 Map 2 Forest Loss in the Peruvian Amazon Figure 2 Between 2001-2017 39 Forest Loss in Peru 38 Map 3 Figure 3 National Natural Protected Areas Species Richness of Select Taxonomic Managed by SERNANP 43 Groups in Peru 40 Map 4 Figure 4 Forest Use Designations 45 Number of Threatened Plant Species 41 Figure 5 Number of Threatened Animal Species 41 Figure A5 1 Forest Loss in Selected Regions 135 LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Table A2 1 Actions Necessary to Conserve Biodiversity Weekly Activities and Milestones 118 (Tropical Forests and Marine Ecosystems) 15 Table A5 1 Table 2 Ecosystem Categories 128 Policies and Other Legal Instruments Relevant for Biodiversity and Tropical Table A5 2 Forest Conservation 59 National Natural Protected Areas 130 Table 3 Table A5 3 Actions Necessary to Conserve Biodiversity CITES Listed Animal Species 133 (Tropical -

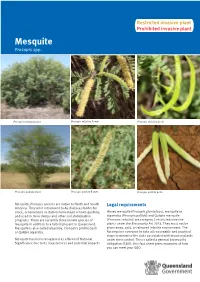

Mesquite Prosopis Spp

Restricted invasive plant Prohibited invasive plant Mesquite Prosopis spp. Prosopis velutina plant Prosopis velutina flower Prosopis velutina pods Prosopis pallida plant Prosopis pallida flower Prosopis pallida pods Mesquite, Prosopis species are native to North and South Legal requirements America. They were introduced to Australia as fodder for stock, ornamentals in station homestead or town gardens, Honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), mesquite or and used in mine dumps and other soil stabilisation algarroba (Prosopis pallida) and Quilpie mesquite programs. There are currently three known species of (Prosopis velutina) are category 3 restricted invasive mesquite in addition to a hybrid present in Queensland. plants under the Biosecurity Act 2014. They must not be Mesquite is also called algaroba, Cloncurry prickle bush given away, sold, or released into the environment. The or Quilpie algaroba. Act requires everyone to take all reasonable and practical steps to minimise the risks associated with invasive plants Mesquite has been recognised as a Weed of National under their control. This is called a general biosecurity Significance due to its invasiveness and potential impacts. obligation (GBO). This fact sheet gives examples of how you can meet your GBO. At a local level, each local government must have a Seeds can lay dormant for years, and mesquite seedlings biosecurity plan that covers invasive plants in its area. can therefore reappear in areas that have been previously This plan may include actions to be taken on certain cleared. species. Some of these actions may be required under local laws. Contact your local government for more Methods of spread information. The major method of spread of mesquite is by dispersal of All other mesquite species are prohibited invasive plants seeds in the faeces of stock.