General News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Prosopis Glandulosa (Mesquite) Invasion in the Arid Environment of South Africa Using Remote Sensing Techniques

Mapping Prosopis glandulosa (mesquite) invasion in the arid environment of South Africa using remote sensing techniques NYASHA FLORENCE MURERIWA 0604748V Supervisor: Dr Elhadi Adam A dissertation submitted to the School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Sciences March 2016 Johannesburg South Africa Abstract Decades after the first introduction of the Prosopis spp. (mesquite) to South Africa in the late 1800s for its benefits, the invasive nature of the species became apparent as its spread in regions of South Africa resulting in devastating effects to biodiversity, ecosystems and the socio- economic wellbeing of affected regions. Various control and management practices that include biological, physical, chemical and integrated methods have been tested with minimal success as compared to the rapid spread of the species. From previous studies, it has been noted that one of the reasons for the low success rates in mesquite control and management is a lack of sufficient information on the species invasion dynamic in relation to its very similar co-existing species. In order to bridge this gap in knowledge, vegetation species mapping techniques that use remote sensing methods need to be tested for the monitoring, detection and mapping of the species spread. Unlike traditional field survey methods, remote sensing techniques are better at monitoring vegetation as they can cover very large areas and are time-effective and cost- effective. Thus, the aim of this research was to examine the possibility of mapping and spectrally discriminating Prosopis glandulosa from its native co-existing species in semi-arid parts of South Africa using remote sensing methods. -

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

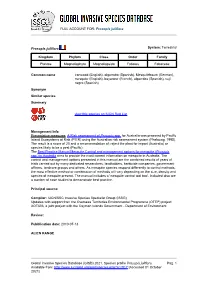

Prosopis Juliflora Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Prosopis juliflora Prosopis juliflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Fabales Fabaceae Common name ironwood (English), algarrobo (Spanish), Mesquitebaum (German), mesquite (English), bayarone (French), algarroba (Spanish), cují negro (Spanish) Synonym Similar species Summary view this species on IUCN Red List Management Info Preventative measures: A Risk assessment of Prosopis spp. for Australia was prepared by Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER) using the Australian risk assessment system (Pheloung, 1995). The result is a score of 20 and a recommendation of: reject the plant for import (Australia) or species likely to be a pest (Pacific). The Best Practice Manual Mesquite Control and management options for mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in Australia aims to provide the most current information on mesquite in Australia. The control and management options presented in this manual are the combined results of years of trials carried out by many dedicated researchers, landholders, herbicide companies, government officers, landcare groups and others. As mesquite species respond differently to control methods, the most effective method or combination of methods will vary depending on the size, density and species of mesquite present. The manual includes a 'mesquite control tool box'. Included also are a number of case studies to demonstrate best practice. Principal source: Compiler: IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) Updates with support from the Overseas -

Moths of the Douglas Lake Region (Emmet and Cheboygan Counties), Michigan: VI

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 35 Number 1 - Spring/Summer 2002 Number 1 - Article 10 Spring/Summer 2002 April 2002 Moths of the Douglas Lake Region (Emmet and Cheboygan Counties), Michigan: VI. Miscellaneous Small Families (Lepidoptera) Edward G. Voss University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Voss, Edward G. 2002. "Moths of the Douglas Lake Region (Emmet and Cheboygan Counties), Michigan: VI. Miscellaneous Small Families (Lepidoptera)," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 35 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol35/iss1/10 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Voss: Moths of the Douglas Lake Region (Emmet and Cheboygan Counties), 2002 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 53 MOTHS OF THE DOUGLAS LAKE REGION (EMMET AND CHEBOYGAN COUNTIES), MICHIGAN: VI. MISCELLANEOUS SMALL FAMILIES (LEPIDOPTERA) Edward G. Voss1 ABSTRACT Forty-seven species in nine families of Lepidoptera (Hepialidae, Psychidae, Alucitidae, Sesiidae, Cossidae, Limacodidae, Thyrididae, Pterophoridae, Epiplemi- dae) are listed with earliest and latest recorded flight dates in Emmet and Cheboy- gan counties, which share the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. The records are from the principal institutional and private collections of Michigan moths and continue the documented listing of Lepidoptera in the region. ____________________ Emmet and Cheboygan counties share the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, the former bordered on the west by Lake Michigan and the latter, on the east by Lake Huron. -

Zootaxa, Carmenta Chromolaenae Eichlin, a New Species (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae)

Zootaxa 2288: 42–50 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Carmenta chromolaenae Eichlin, a new species (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) for the biological control of Chromolaena odorata (L.) King & Robinson (Asteraceae) THOMAS D. EICHLIN1, OONA S. DELGADO3, LORRAINE W. STRATHIE2, COSTAS ZACHARIADES2, & JOSE CLAVIJO3 11367 E. Washington Ave., Gilbert, Arizona 85234, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Agricultural Research Council-Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X6006, Hilton, SOUTH AFRICA. E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] 3 Museo del Instituto de Zoologia Agricola, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Maracay, VENEZUELA. E-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract A new species of Sesiidae, Carmenta chromolaenae Eichlin, is described to make the name available to researchers evaluating the moth's potential for biological control of its host plant, Chromolaena odorata, in South Africa and other parts of the plant's invasive range. This clearwing moth species was reared from the host plant in Venezuela. The adult moth, including the male and female genitalia, larva, and pupa are described and illustrated. Its biology and possible use as a control agent are discussed. Key words: Sesiidae, Carmenta, new species, description, Venezuela, South Africa, biological control, host plant, biology, genitalia, larva, pupa Introduction During efforts to discover herbivores of the perennial woody shrub Chromolaena odorata (L.) King & Robinson (Asteraceae), an undescribed species of Carmenta (Sesiidae) was reared. The host plant is commonly referred to as “chromolaena,” “Siam weed,” or “Jack in the bush” and is native to the subtropics and tropics of the Americas. -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Biology of the Bruchidae +6178

Ann. Rev. Entomol 1979. 24:449-73 Copyright @ 1979 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved BIOLOGY OF THE BRUCHIDAE +6178 B. J. Southgate Biology Department, Pest Infestation Control Laboratory, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, Slough SL3 7HJ, Berks, England INTRODUCTION Species of Bruchidae breed in every continent except Antarctica. The larg est number of species live in the tropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Many species have obvious economic importance because they breed on grain legumes and consume valuable proteins that would otherwise be eaten by man. Other species, however, destroy seeds of an immense number of leguminous trees and shrubs, which, though they have no obvious economic value, stem the advance of the deserts into the marginal cultivated areas of the world. When this ecosystem is mismanaged by practices such as over grazing, then any organism that restricts the normal regeneration of seed lings will, in the long run, affect agriculture adversely. This has been demonstrated recently in some African and Middle Eastern semiarid zones (65). The present interest in the management of arid areas and in the introduc Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1979.24:449-473. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by Copyright Clearance Center on 11/01/20. For personal use only. tion of alternative tree species to provide timber, fodder, or shade has stimulated a detailed study of the ecology of some leguminous trees and shrubs that has revealed some deleterious effects of bruchid beetles on the seeds of these plants (42, 43, 59). It has also emphasized the inadequacy of our knowledge of the taxonomy and biology of these beetles. -

Identification and Quantification of Headspace Volatile Constituents of Okpehe, Fermented Prosopis Africana Seeds *Onyenekwe, P

International Food Research Journal 21(3): 1193-1197 (2014) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Identification and quantification of headspace volatile constituents of okpehe, fermented Prosopis africana seeds *Onyenekwe, P. C., Odeh, C. and Enemali, M. O. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Nasarawa State University, P. M. B. 1022, 930001 Keffi, Nigeria Article history Abstract Received: 23 July 2013 The volatile components of the fermented seeds of Prosopis africana, (okpehe), were determined. Received in revised form: Traditional method of production was used. The volatile constituents were analyzed by Gas 16 January 2014 Accepted: 18 January 2014 Chromatography using the PDMS-SPME head space technique and identification of volatiles was by comparing their retention time and mass spectra with those of the library. In all, there Keywords are about 51 volatile components with 8 alcohols, 15 aldehydes, 8 ketones, 2 acetates, 11 Condiment benzene derivatives, 4 alkanes, 2 alkenes and 4 others. The aldehydes constitutes the bulk of Fermented the volatiles followed by the pyrazines. Most of the identified compounds are known to have Flavour strong impact on the flavour and fragrance of fermented and roasted products. Okpehe Prosopis africana Volatile components © All Rights Reserved Introduction Extraction of Prosopis seed is generally difficult because the seeds are imbedded in a pulpy mesocarp Okpehe, a fermented flavouring food condiment, within a hard dry pod. Grinding mills have been used most popular in the middle belt of Nigeria, is produced to remove the outer dry pod. The pods are then soaked from Prosopis africana, a leguminous oil seed. It is in a 0.1 M solution of hydrochloric acid for 24 hours. -

A New Species of Clearwing Moth, Carmenta Laurelae (Sesiidae)

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 39(4), 1985, 262-265 A NEW SPECIES OF CLEAR WING MOTH, CARMENTA LAURELAE (SESIIDAE), FROM FLORIDA LARRY N. BROWN Department of Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620 THOMAS D . EICHLIN Insect Taxonomy Laboratory, A. & I., Division of Plant Industry, California Department of Food and Agriculture, Sacramento, California 95814 AND J. WENDELL SNOW Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, U.S.D.A., Byron, Georgia 31008 ABSTRACT. A new species of clear wing moth, Carmenta laurelae, was discovered in west-central Florida using the synthetic pheromone, (Z,Z) 3, 13-octadecadien-1-ol acetate and is herein described. The type series consists of 75 male specimens which were taken only in cypress swamps and the adjacent forested floodplain habitats. The flight period of the adult males occurred from 1100-1400 h daily. Adults were captured only between 13 May to 3 June 1985 in the Tampa Bay area. Although the North American sesiids have been the subject of two monographs (Beutenmuller, 1901; and Engelhardt, 1946), the fauna is still imperfectly known. The development of several chemical sex at tractants by Tumlinson and colleagues (1974) and Schwarz and col leagues (1983) has greatly aided the collecting of clear wing species and also helped elucidate their ecological and taxonomic relationships (Duckworth & Eichlin, 1977). While using a variety of sesiid sex attractants to survey for the moths in the Tampa Bay area of west-central Florida during 1985, a new species of clearwing moth was captured in May and early June. The description of this species follows. -

Insect Interactions in a Biological Control Context Using Water Hyacinth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) “Is more, less?” Insect – insect interactions in a biological control context using water hyacinth as a model A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE of Rhodes University By Philip Sebastian Richard Weyl December 2011 Abstract Interactions between insects have been shown to be important regulators of population abundances and dynamics as well as drivers of spatial segregation and distribution. These are important aspects of the ecology of insects used in biological control and may have implications for the overall success of a particular programme. In the history of biological control there has been a tendency to release a suite of agents against a weed, which in some cases has increased the level of success, while in others little change has been observed. In most of these cases the implications of increasing the level of complexity of the system is not taken into account and there is little research on the effect of releasing another agent into the system. A brief meta-analysis was done on all the biological control programmes initiated in South Africa. Emphasis was placed on multi-species releases and the effects that overlapping niches were having on the number of agents responsible for the success of a programme. Where overlapping niches were present among agents released the number of agents responsible for success was lower than the number established. Water hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes (Martius) Solms-Laubach in South Africa has more arthropod agents released against it than anywhere else in the world, yet control has been variable. -

Invasive Alien Flora and Fauna in South Africa: Expertise and Bibliography

Invasive alien flora and fauna in South Africa: expertise and bibliography by Charles F. Musil & Ian A.W. Macdonald Pretoria 2007 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 September 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibilities relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI is to be the leading institution in biodiversity science in Africa, facilitating conservation, sustainable use of living resources, and human wellbeing. SANBI’s mission is to promote the sustainable use, conservation, appreciation and enjoyment of the exceptionally rich biodiversity of South Africa, for the benefit of all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series publishes occasional reports on projects, technologies, workshops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Technical editor: Gerrit Germishuizen and Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Daleen Maree Cover design: Sandra Turck The authors: C.F. Musil—Senior Specialist Scientist, Global Change & Biodiversity Program, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, Claremont, 7735 ([email protected]) I.A.W. Macdonald—Extraordinary Professor, Sustainability Institute, School of Public Management and Planning, Stellenbosch University ([email protected]) How to cite this publication MUSIL, C.F. & MACDONALD, I.A.W. 2007. Invasive alien flora and fauna in South Africa: expertise and bibliography.