Brunei International Medical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australians Into Battle : the Ambush at Gema S

CHAPTER 1 1 AUSTRALIANS INTO BATTLE : THE AMBUSH AT GEMA S ENERAL Percival had decided before the debacle at Slim River G that the most he could hope to do pending the arrival of further reinforcements at Singapore was to hold Johore. This would involve giving up three rich and well-developed areas—the State of Selangor (includin g Kuala Lumpur, capital of the Federated Malay States), the State of Negr i Sembilan, and the colony of Malacca—but he thought that Kuala Lumpu r could be held until at least the middle of January . He intended that the III Indian Corps should withdraw slowly to a line in Johore stretching from Batu Anam, north-west of Segamat, on the trunk road and railway , to Muar on the west coast, south of Malacca . It should then be respon- sible for the defence of western Johore, leaving the Australians in thei r role as defenders of eastern Johore. General Bennett, however, believing that he might soon be called upo n for assistance on the western front, had instituted on 19th December a series of reconnaissances along the line from Gemas to Muar . By 1st January a plan had formed in his mind to obtain the release of his 22nd Brigade from the Mersing-Jemaluang area and to use it to hold the enem y near Gemas while counter-attacks were made by his 27th Brigade on the Japanese flank and rear in the vicinity of Tampin, on the main road near the border of Malacca and Negri Sembilan . Although he realised tha t further coastal landings were possible, he thought of these in terms of small parties, and considered that the enemy would prefer to press forwar d as he was doing by the trunk road rather than attempt a major movement by coastal roads, despite the fact that the coastal route Malacca-Muar- Batu Pahat offered a short cut to Ayer Hitam, far to his rear . -

Menganalisis Pola Dan Arah Aliran Hujan Di Negeri Sembilan Menggunakan Kaedah GIS Poligon Thiessen Dan Kontur Isoyet

GEOGRAFIA OnlineTM Malaysian Journal of Society and Space 2 (105 - 113) 105 © 2006, ISSN 2180-2491 Menganalisis pola dan arah aliran hujan di Negeri Sembilan menggunakan kaedah GIS poligon Thiessen dan kontur Isoyet Shaharuddin Ahmad1, Noorazuan Md. Hashim1 1School of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Correspondence: Shaharuddin Ahmad (email: [email protected]) Abstrak Curahan hujan seringkali digunakan sebagai indeks iklim bagi menentukan perubahan dalam kajian perubahan iklim global. Frekuensi dan tempoh curahan hujan dianggap sebagai indeks penting bagi bidang geomorfologi, hidrologi dan kajian cerun. Di samping itu, maklumat tentang taburan hujan penting kepada manusia kerana boleh mempengaruhi pelbagai aktiviti manusia seperti pertanian, perikanan dan pelancongan. Oleh itu, kajian ini meneliti pola taburan dan tren hujan yang terdapat di Negeri Sembilan. Data hujan bulanan dan tahunan untuk tempoh 21 tahun (1983 – 2003) dibekalkan oleh Perkhidmatan Kajicuaca Malaysia (MMS) bagi lapan stesen kajiklim yang terdapat di seluruh negeri. Kaedah GIS Poligon Thiessen dan Kontur Isoyet digunakan bagi mengira dan menentukan pola taburan hujan manakala kaedah Ujian Mann-Kendall digunakan bagi mengesan pola perubahan tren dan variabiliti hujan. Hasil kajian menunjukkan bahawa berdasarkan kaedah Persentil dan Kontur Isoyet, pola taburan hujan di Negeri Sembilan boleh di kategorikan kepada dua jenis kawasan iaitu kawasan sederhana lembap (memanjang dari Jelebu -Kuala Pilah-Gemencheh) dan kawasan hujan lebat (sekitar kawasan pinggir pantai-Seremban- Chembong). Pola perubahan hujan didapati tidak tetap bagi kesemua stesen kajian bagi tempoh kajian ini. Berasaskan Ujian Mann-Kendall tahun 1980-an dan 1990-an menandakan tahun perubahan taburan hujan bagi kesemua stesen kajian yang boleh memberi kesan kepada kawasan tadahan dan seterusnya menentukan kadar bekalan air yang mencukupi. -

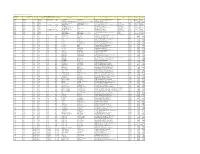

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-180 ISSUE 16, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Copyright Page Issue 16, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 16, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Table of Contents 1. -

Usp Register

SURUHANJAYA KOMUNIKASI DAN MULTIMEDIA MALAYSIA (MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION) USP REGISTER July 2011 NON-CONFIDENTIAL SUMMARIES OF THE APPROVED UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLANS List of Designated Universal Service Providers and Universal Service Targets No. Project Description Remark Detail 1 Telephony To provide collective and individual Total 89 Refer telecommunications access and districts Appendix 1; basic Internet services based on page 5 fixed technology for purpose of widening communications access in rural areas. 2 Community The Community Broadband Centre 251 CBCs Refer Broadband (CBC) programme or “Pusat Jalur operating Appendix 2; Centre (CBC) Lebar Komuniti (PJK)” is an nationwide page 7 initiative to develop and to implement collaborative program that have positive social and economic impact to the communities. CBC serves as a platform for human capital development and capacity building through dissemination of knowledge via means of access to communications services. It also serves the platform for awareness, promotional, marketing and point- of-sales for individual broadband access service. 3 Community Providing Broadband Internet 99 CBLs Refer Broadband access facilities at selected operating Appendix 3; Library (CBL) libraries to support National nationwide page 17 Broadband Plan & human capital development based on Information and Communications Technology (ICT). Page 2 of 98 No. Project Description Remark Detail 4 Mini Community The ultimate goal of Mini CBC is to 121 Mini Refer Broadband ensure that the communities living CBCs Appendix 4; Centre within the Information operating page 21 (Mini CBC) Departments’ surroundings are nationwide connected to the mainstream ICT development that would facilitate the birth of a society knowledgeable in the field of communications, particularly information technology in line with plans and targets identified under the National Broadband Initiatives (NBI). -

Senarai Premis Penginapan Pelancong : N.Sembilan

SENARAI PREMIS PENGINAPAN PELANCONG : N.SEMBILAN BIL. NAMA PREMIS ALAMAT POSKOD DAERAH 1 Avillion Port Dickson Batu 3, Jalan Pantai 71000 Port Dickson 2 Bayu Beach Resort 4 1/2 Miles, Jalan Pantai, Si Rusa 71050 Port Dickson 3 ACBE Hotel No 524-526, Lorong 12, Taman ACBE 72100 Bahau 4 Hotel Seri Malaysia Seremban Jalan Sg Ujong 70200 Seremban 5 Thistle Hotel Port Dickson KM 16, Jalan Pantai, Teluk Kemang 71050 Port Dickson 6 Hotel We Young 241E, 7 1/2 Miles, Jalan Pantai, Si Rusa 71050 Port Dickson 7 Casa Rachado Resort Tanjung Biru, Batu 10, Jalan Pantai, Si Rusa 71050 Port Dickson 8 Corus Paradise Resort Port Dickson 3.5KM, Jalan Pantai 71000 Port Dickson 9 Desa Inn Lot 745, Jalan Dato'Abdul Manap 72000 Kuala Pilah 10 Glory Beach Resort Batu 2, Jalan Seremban, Tanjung Gemuk 71000 Port Dickson 11 The Regency Tanjung Tuan Beach Resort 5th. Mile, Jalan Pantai, 71050 Port Dickson 12 Eagle Ranch Resort Lot 544, Batu 14, Jalan Pantai 71250 Port Dickson 13 Tampin Hotel SH29-32, Pekan Woon Hoe Kan 73000 Tampin 14 Bahau Hotel 8-11, Tingkat 2 & 3, Lorong 1, Taman ACBE 72100 Bahau 15 Seremban Inn Hotel No 39, Jalan Tuanku Munawir 70000 Seremban 16 Carlton Star Hotel 47, Jalan Dato'Sheikh Ahmad 70000 Seremban 17 Lido Hotel Batu 8, Jalan Pantai Teluk Kemang 71050 Port Dickson 18 Bougainvilla Resort NO. 1178, Batu 9, JLN KEMANG 12, Teluk Kemang 71050 Port Dickson 19 Kong Ming Hotel KM 13, Jalan Pantai, Teluk Kemang, Si Rusa 71050 Port Dickson 20 Beach Point Hotel Lot 2261, Batu 9, Jalan Pantai, Si Rusa 71000 Port Dickson 21 Hotel Seri Malaysia Port -

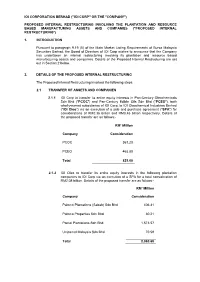

Proposed Internal Restructuring

IOI CORPORATION BERHAD ("IOI CORP" OR THE "COMPANY") PROPOSED INTERNAL RESTRUCTURING INVOLVING THE PLANTATION AND RESOURCE BASED MANUFACTURING ASSETS AND COMPANIES ("PROPOSED INTERNAL RESTRUCTURING") 1. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to paragraph 9.19 (5) of the Main Market Listing Requirements of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad, the Board of Directors of IOI Corp wishes to announce that the Company has undertaken an internal restructuring involving its plantation and resource based manufacturing assets and companies. Details of the Proposed Internal Restructuring are set out in Section 2 below. 2. DETAILS OF THE PROPOSED INTERNAL RESTRUCTURING The Proposed Internal Restructuring involved the following steps. 2.1 TRANSFER OF ASSETS AND COMPANIES 2.1.1 IOI Corp to transfer its entire equity interests in Pan-Century Oleochemicals Sdn Bhd ("PCOC") and Pan-Century Edible Oils Sdn Bhd ("PCEO"), both wholly-owned subsidiaries of IOI Corp, to IOI Oleochemical Industries Berhad ("IOI Oleo") via an execution of a sale and purchase agreement ("SPA") for considerations of RM0.36 billion and RM0.46 billion respectively. Details of the proposed transfer are as follows:- RM’ Million Company Consideration PCOC 361.20 PCEO 463.88 Total 825.08 2.1.2 IOI Oleo to transfer its entire equity interests in the following plantation companies to IOI Corp via an execution of a SPA for a total consideration of RM2.08 billion. Details of the proposed transfer are as follows:- RM’ Million Company Consideration Palmco Plantations (Sabah) Sdn Bhd 406.31 Palmco Properties Sdn Bhd 30.21 Pamol Plantations Sdn Bhd 1,573.57 Unipamol Malaysia Sdn Bhd 70.59 Total 2,080.68 2.1.3 IOI Corp to transfer seven (7) estates located in Peninsular Malaysia and part of Paya Lang estate measuring in total of approximately 15,396.41 hectares and its entire equity interest in IOI Pelita Plantation Sdn Bhd ("IOI Pelita"), a 70% owned subsidiary company, to IOI Plantation Sdn Bhd ("IOI Plantation") via an execution of SPAs for considerations of RM1.02 billion and RM44.32 million respectively. -

1970 Population Census of Peninsular Malaysia .02 Sample

1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE DATA DOCUMENTATION AND CODEBOOK 1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE CONTENTS Page TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON THE DATA TAPE 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA FILE 2 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1: HOUSEHOLD RECORD 4 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2: PERSON RECORD (AGE BELOW 10) 5 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3: PERSON RECORD (AGE 10 AND ABOVE) 6 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1 7 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2 15 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3 24 APPENDICES: A.1: Household Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 4) 33 A.2: Individual Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 5) 34 B.1: List of State and District Codes 35 B.2: List of Codes of Local Authority (Cities and Towns) Codes within States and Districts for States 38 B.3: "Cartographic Frames for Peninsular Malaysia District Statistics, 1947-1982" by P.P. Courtenay and Kate K.Y. Van (Maps of Adminsitrative district boundaries for all postwar censuses). 70 C: Place of Previous Residence Codes 94 D: 1970 Population Census Occupational Classification 97 E: 1970 Population Census Industrial Classification 104 F: Chinese Age Conversion Table 110 G: Educational Equivalents 111 H: R. Chander, D.A. Fernadez and D. Johnson. 1976. "Malaysia: The 1970 Population and Housing Census." Pp. 117-131 in Lee-Jay Cho (ed.) Introduction to Censuses of Asia and the Pacific, 1970-1974. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Population Institute. -

PDF Senarai Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara

Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 MAKLUMAT ALAMAT, NO TELEFON DAN FAKS PAGN Bil ALAMAT NO TEL EMAIL JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Batu Pahat No. 7, Jalan Gunung Soga 1 - [email protected] 83000, Batu Pahat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Felda Tenggaroh 2 No.1, Jalan Cempaka 2 07-7911059 [email protected] Felda Tenggaroh 2 86810 Mersing JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Parit Guntong TLJM 336 Parit Guntong 3 07-4163036 [email protected] Mukim Lubok, Semerah 83600, Batu Pahat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Segamat LOT 15550 Mukim Sg Segamat 4 Bandar Putra 07-9432385 [email protected] 85000 Segamat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Kulaijaya LOT 23780, Jalan Sri Putri 1/13 07-6623117 5 [email protected] Taman Putri, 81000 Kulaijaya 07-6623257 JOHOR Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Pasir Gudang PTD 158017 Persimpangan Jalan 6 Gunung 07-3861070 [email protected] Jalan Gunung 41, Bandar Sri Alam 81750 Masai JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Pengerang Lot PTD 7329, Taman Bayu Damai 7 Mukim Pantai Timur, Daerah Kecil 07-8263075 [email protected] Pengerang 81620, Kota Tinggi, Johor Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 Bil ALAMAT NO TEL EMAIL MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Bukit Peringgit 8 No. 47 Kuarters Kerajaan 06-2821309 [email protected] 75150 Bukit Peringgit MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Jasin Lot PT 5566, Jalan Melaka, Taman 9 Bahagia 06-5292791 [email protected] 77000, Jasin MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Bukit Katil Lot PT 5497, Kawasan MITC, Ayer 10 06-2325173 [email protected] -

Klinik Perubatan Swasta Negeri Sembilan Sehingga Disember 2020

Klinik Perubatan Swasta Negeri Sembilan Sehingga Disember 2020 NAMA DAN ALAMAT KLINIK KLINIK SEREMBAN 300 Senawang Jaya 70450 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK TEH HENG ONG SDN BHD 2633, Simpang Lukut Jalan Sepang 71010 Port Dickson KLINIK REMBAU 1014, Off Jalan Besar 71300 Rembau Negeri Sembilan KLINIK PAKAR KANAK-KANAK KIDDI CARE No. 293_G, Taman AST Jalan Sg. Ujung, 70200 Seremban Negeri Sembilan POLIKLINIK AMAN 74, Jalan Besar Pekan Nilai 71800 Nilai KLINIK BAKTI 149, Jalan Yam Tuan Raden 72000 Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK CARE4ME PT 12948, Jalan BBN 1/7D Putra Indah Bandar Baru Nilai 71800 Nilai, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK HEE, ANNANDAN & SIVA 4 Jalan Lintang 73400 Gemas, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK AMMANPAL 5799, Jalan TS 2/7G, Taman Semarak 2 71800 Nilai, Negeri Sembilan ALEEN MEDICAL CENTRE 519 Jalan Tuanku Antah 70100 Seremban Negeri Sembilan KLINIK HEE No. 32, Jalan Besar Batang Melaka 73300 Tampin, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK PAKAR ORTOPEDIK PHANG & WANITA YANG No. 48, Jalan Tunku Hassan 70000 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK A.K. CHONG 57 Jalan Temiang (Grd Floor) 70200 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK AISYAH DAN YUSOF B 25, KLIA Business Centre Jalan Pusat Niaga KLIA 2, Kuarters KLIA 71800 Nilai, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK HEE Bangunan UMNO, Gemencheh 73200 Tampin, Negeri Sembilan POLIKLINIK PERDANA & X-RAY PT 9924, Ground Floor & 1st Floor Jalan BBN 1/3 G, Putra Point Fasa II A, Bandar Baru Nilai 71800 Nilai, Negeri Sembilan KLINIK NAGIAH 137, Jalan Damai 72100 Bahau KELINIK LEE 124, Jalan Yam Tuan 72000 Kuala Pilah KLINIK RAMANI 2026 Taman Ria KM 4, Jalan Seremban 71000 Port Dickson KLINIK KHOO 2827, Jalan SJ 3/6A Seremban Jaya 70450 Seremban KLINIK LEE PT 4963, Jalan T/S 2/1 Taman Semarak, Nilai 71800 seremban KLINIK TAN & SURGERY 2742 Main Road 71200 Rantau KLINIK PANTAI Lot 2747, Jalan Besar 71200 Rantau Negeri Sembilan KLINIK CHUA No. -

Senarai Nama Adun Penggal Ke14

SENARAI NAMA ADUN PENGGAL KE14 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA PARTI P.126-JELEBU N.01 - CHENNAH LOKE SIEW FOOK PH P.126-JELEBU N.02 - PERTANG NOOR AZMI BIN YUSOF BN P.126-JELEBU N.03 - SUNGAI LUI MOHD.RAZI BIN MOHD.ALI BN P.126-JELEBU N.04 - KLAWANG BAKRI BIN SAWIR PH P.127-JEMPOL N.05 -SERTING DATO SHAMSHULKAHAR BIN MOHD DELI BN P.127-JEMPOL N.06 - PALONG DATO MUSTAPHA BIN NAGOOR BN P.127-JEMPOL N.07 - JERAM MANICKAM A/L LETCHUMAN BN PADANG P.127-JEMPOL N.08 - BAHAU TEO KOK SEONG PH P.128-SEREMBAN N.09 - LENGGENG SUHAIMI BIN KASSIM PH P.128-SEREMBAN N.10 - NILAI ARUL KUMAR A/L JAMBUNATHAN PH P.128-SEREMBAN N.11 - LOBAK CHEW SEH YONG PH P.128-SEREMBAN N.12 - TEMIANG NG CHIN TSAI PH P.128-SEREMBAN N.13 - SIKAMAT DATO SERI HAJI AMINUDDIN BIN HAJI HARUN PH BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA PARTI P.128-SEREMBAN N.14 - AMPANGAN DATO DR. MOHAMAD RAFIE BIN AB MALEK PH P.129-KUALA PILAH N.15 - JUASSEH DATO' HAJI ISMAIL BIN LASIM BN P.129-KUALA PILAH N.16 - SERI MENANTI DATO' HAJI ABD SAMAD BIN IBRAHIM BN P.129-KUALA PILAH N.17 - SENALING DATO' HAJI ADNAN BIN ABU HASSAN BN P.129-KUALA PILAH N.18 - PILAH MOHAMAD NAZARUDDIN BIN SABTU PH P.129-KUALA PILAH N.19 - JOHOL HAJI SAIFUL YAZAN BIN SULAIMAN BN P.130-RASAH N.20 - LABU HAJI ISMAIL BIN HAJI AHMAD PH P.130-RASAH N.21 - BUKIT TAN LEE KOON PH KEPAYANG P.130-RASAH N.22 - RAHANG MARY JOSEPHINE PRITTAM SINGH BEBAS P.130-RASAH N.23 - MAMBAU YAP YEW WENG PH P.130-RASAH N.24 SEREMBAN JAYA GUNASEKAREN A/L PALASAMY PH P.131-REMBAU N.25 - PAROI DATO HAJI MOHAMAD TAUFEK BIN ABD GHANI PH P.131-REMBAU N.26 - CHEMBONG DATO' ZAIFULBAHRI BIN IDRIS BN BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA PARTI P.131-REMBAU N.27 - RANTAU DATO' SERI UTAMA MOHAMAD BIN HAJI HASAN BN P.131-REMBAU N.28 - KOTA DATO' DR. -

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State 2M Automotive Automotive 22 GROUND FLOOR JALAN DATO SHEIKH AHMAD SEREMBAN N

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State 2M Automotive Automotive 22 GROUND FLOOR JALAN DATO SHEIKH AHMAD SEREMBAN NEGERI SEMBILAN70000 Negeri Sembilan Abul Kalam enterprise Automotive Abul Kalam enterprise no 25 Jalan 3/1 Nilai3 Negeri Sembilan Aby Tyre Centre Automotive LOT 687 KG SASAPAN BATU REMBAU BERANANG Negeri Sembilan ADIB SUCCESS GARAGE Automotive TANJONG IPOH NO 32 Tanjung Ipoh Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri Sembilan Ah Keong Motor Service Automotive 138139 jalan tampin 4 1/2 miles senawang light industrial area 70450 seremban Negeri sembilan Jalan Tampin Seremban Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri Sembilan Ah Keong Motor Svc Automotive LOT 138 & 139, SENAWANG LIGHT IND AREA, BT 4 1/2, JALAN TAMPIN 70450, SEREMBAN NEGERI SEMBILAN70450 Negeri Sembilan AJ AVENUE CAR WASH Automotive NO 21 JALAN HARTAMAS 2 Jalan Seremban Taman Port Dickson Port Dickson Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri Sembilan alat alat ganti kenderaan Automotive Jalan Selandar Gemencheh Gemencheh Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri Sembilan AMIR IMRAN ENTERPRISE Automotive Imran Carpets205 JALAN 3/6 NILAI 3 Lot 205 Jalan Nilai 3/6 Kawasan Perindustrian Nilai 3 Nilai Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri Sembilan ARH Auto Care Seremban Automotive No.93 Jalan MSJ 4,Medan Perniagaan SenawangNegeri Sembilan Negeri Sembilan Arh Auto Care Sg Gadut Automotive No 41G, Jalan TJ 1/4A,Kawasan Perindustrian Tuanku Jaafar, Sungai Gadut,Negeri Sembilan Negeri Sembilan Asia Access Parking Automotive C/O Asia Access Parkig No10 Jalan Wolff Seremban Negeri Sembilan Malaysia Negeri