Political Economy Thomas Plümper Version 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Handler, Heinz Working Paper The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area WIFO Working Papers, No. 446 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Handler, Heinz (2013) : The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area, WIFO Working Papers, No. 446, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/128970 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler 446/2013 The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler WIFO Working Papers, No. -

17Th Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements

BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1st APRIL 1946—31st MARCH 1947 BASLE 16th June 1947 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introductory Remarks 5 II. Transition from War to Peace Economy 9 Budget situation (p. 9), resources for productive investments (p. 9), subsidies (p. 10), nationalisations (p. 11), financial accounts (p. 11), foreign credits and foreign aid (p. 13)., em- ployment policy (p. 14), shortage of consumption goods (p. 15), wage increases (p. 15), price control (p. 16), wheat situation (p. I"]), meat, fat etc. (p. 18), industrial production (p. 20 ), coal , situation (p. 22), over-employment (p. 25) . III. Price Movements 28 Types of movement (p. 28), prices in Greece (p. 28), Hungary (p. 28), Roumania (p. 29), China (p. 29), Poland (p. 30), Italy (p. 30), France (p. 31), Finland (p. 32), Bulgaria (p. 32), Belgium (p. 32), Czechoslovakia (p. 32), Holland (p. 32), Turkey (p. 32), United States (p. 33), Great Britain (p. 35), Germany (p. 36), Austria (p. 37), wartime shortages (p. 38), general observations (p. 39) IV. Recovery of Foreign Trade .................. 41 Volume of world trade (p. 41), foreign trade in the United States (p. 42), in Canada (p. 45), Great Britain (p. 46), Denmark (p. 49), Norway (p. 49), Sweden (p. 5°), Finland (p. 50), Belgium (p. 51), Holland (p. 51), Switzerland (p. 52), Portugal (p. 52), France (p. 52), Italy (p. 54), Germany (p. 55), Poland (p. 5&), Czechoslovakia (p. 57), Austria (p. 58), Hungary (p. 58), Roumania (p. 59), Yugoslavia (p. 59), Bulgaria (p. 59), Greecç (p. 59); Turkey (p. 60), U.S.S.R. -

Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D

World Coins Session D Begins at 14:00 PST on Friday, January 20, 2017 1349. BAVARIA: Karl Albert, 1726-1745, AV ½ karolin, Munich mint, 1729, KM-406, Fr-230, bust right of king // crowned World Coins Madonna holding Christ child and coat-of-arms, much original luster, AU $600 - 800 Europe (continued) 1345. AUGSBURG: Udalschak, 1184-1202, AR bracteate (0.85g), Berger-2636/39, bust of the bishop, holding crozier & long cross, surrounded by 8 crescents, each filled with a lily, EF $120 - 160 This issue continued under Hartwig II, 1202-1208. 1350. BAVARIA: Karl Theodor, 1777-1799, AR thaler, 1799, KM-600.2, Dav-1966A, Madonna and Child, light reverse adjustment marks, somewhat prooflike, AU $250 - 300 1346. AUGSBURG: Hartmann II, 1250-1286, AR bracteate (0.75g), Berger-2644, enthroned bishop, with crozier & cross, EF $100 - 125 1351. BAVARIA: Maximilian II, 1848-1865, AR 2 thaler, 1856, KM-467, commemorating the Erection of the Monument of Maximilian II at Lindau, AU $400 - 500 1347. AUGSBURG: Anonymous, ca. 1290-1330, AR bracteate (0.56g), Berger-2656/61, head of the bishop, his hands raised before him, holding crozier and the bible, EF $100 - 125 1352. BAVARIA: Ludwig II, 1864-1886, AR thaler, 1865, KM-869, some hairlines, somewhat prooflike, UNC $175 - 225 1348. BAMBERG: Franz Ludwig, 1779-1795, AR thaler, 1795, KM-146, Dav-1939, Contribution thaler, somewhat prooflike, one-year type, made from the silver service of the Bishop, Choice AU $350 - 450 1353. BAVARIA: Otto, 1886-1913, AR 2 mark, 1888-D, KM-905, hairlined, nicely toned, EF $250 - 350 112 Stephen Album Rare Coins | Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D 1354. -

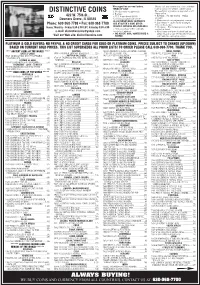

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

Historical Record of Monetary Unions: Lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov • Vol. 6 (55) •No. 2 - 2013 Series V: Economic Sciences HISTORICAL RECORD OF MONETARY UNIONS: LESSONS FOR THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION Ileana TACHE1 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to make a record of previous monetary unions and derive some useful lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union. Evaluating the political economy of the euro through the lens of history, with the help of comparative analysis, can contribute to better understanding the present stage of the EMU and its challenges. Even if the EU is a unique, sui generis, phenomenon, the analytical lessons learned from the historical cases could be applied to the contemporary situation of the euro. Key words: European Economic and Monetary Union, Gold Standard, USA monetary union, monetary unification of Italy, German Zollverein, Latin Monetary Union, Scandinavian Monetary Union. 1. Introduction The study is built on the main contributions Even if euro still appears like a novelty in of the literature in this field, such as Bordo the process of European construction and as and Jonung (1999), Bergman (1999), international currency, it was preceded by a Foreman-Peck (2005), McNamara (2011) few monetary unions on the continent and or de Vanssay (1999). outside of it. While much of the European The paper is organized as follows. The monetary project has indeed been of an next section is dedicated to the Gold ambition never seen in Europe before, the Standard, then the other monetary unions idea of bringing currencies together is far are discussed: USA monetary union after from new. -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

World Bank Document

P ReportN 0. EA-69-a Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared for use within the Bank. In making it available to others, the Bank assumes no responsibility to them for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized JAMAICA - MISSION REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized March 5, 1957 Public Disclosure Authorized Department of Operations Europe, Africa and Australasia CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS 1 Jamaican Pound = 1 Pound Sterling f1 = U.S. $2.80 f 1 Million . U.S. $2.8 million REPOqT uF T-7 ,ISIOE TO JAURICA Page I. Introduction - Purpose of the .ission ............... 1 II. Political and Constitutional Position - Federation of the British Uest-Indies ............... 1 III. Economic Situation ................................. 4 iain Agricultural Exports Tourist Trade Bauxite Importance of 3auxite Revenues to the 3udvet IV. The Develolment Pro,ra, ................. ....... 8 The Programi and the Creditworthiness of the Government V. Possible Projects ................................... 11 1. The Jamaican Governient Railuay 2. The Fort of Kingston 3. Electric -swer 4. Airports 5. Other Projects in the Developent Program 6. Import Requireaents VI. The U.K. Colonial Loans Act ......................... 17 VII. Conclusions .............................. ....... 17 JAMAICA Taoic Dohta Area: 4,400 square miles Population: 1.5 million National income (1952): 906 million Income per head: N6 = ($168) Origin of Gross Donestic Product (1952) 1 -

Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and Currencies in History from Earliest Times to the Euro

E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 3 Money Museum Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and currencies in history from earliest times to the euro Coins and maps from the MoneyMuseum with texts by Ursula Kampmann E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 4 All rights reserved Any form of reprint as well as the reproduction in television, radio, film, sound or picture storage media and the storage and dissemination in electronic media or use for talks, including extracts, are only permissible with the approval of the publisher. 1st edition ??? 2010 © MoneyMuseum by Sunflower Foundation Verena-Conzett-Strasse 7 P O Box 9628 C H-8036 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 242 76 54, Fax: +41 (0)44 242 76 86 Available for free at MoneyMuseum Hadlaubstrasse 106 C H-8006 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 350 73 80, Bureau +41 (0)44 242 76 54 For further information, please go to www.moneymuseum.com and to the Media page of www.sunflower.ch Cover and coin images by MoneyMuseum Coin images p. 56 above: Ph. Grierson, Münzen des Mittelalters (1976); p. 44 and 48 above: M. J. Price, Monnaies du Monde Entier (1983); p. 44 below: Staatliche Münzsammlung München, Vom Taler zum Dollar (1986); p. 56 below: Seaby, C oins of England and the United Kingdom (1998); p. 57: archive Deutsche Bundesbank; p. 60 above: H. Rittmann, Moderne Münzen (1974) Maps by Dagmar Pommerening, Berlin Typeset and produced by O esch Verlag, Zürich Printed and bound by ? Printed in G ermany E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 5 Contents The Publisher’s Foreword . -

Federal Reserve Bulletin January 1947

FEDERAL VE BULLETIN JANUARY 1947 BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM WASHINGTON Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis EDITORIAL COMMITTEE ELLIOTT THURSTON WOODLIEF THOMAS CARL E. PARRY The Federal Reserve BULLETIN is issued monthly under the direction of the staff editorial committee. This committee is responsible for interpretations and opinions expressed, except in official statements and signed articles. CONTENTS PAGE Review of the Month—Recent Market Developments. 1-10 International Monetary Fund Statement Concerning Initial Par Values. 11-12 Report by the Council of Economic Advisers. 13-25 Law Department: Cessation of Hostilities: Statement by the President 26 Cessation of Hostilities of World War II by the President of the United States of America. Proclamation 2714. 26-27 Regulation T: Exercise of Rights to Subscribe .... 27 Transactions of Customers Who Are Brokers or Dealers. 27 Regulation U—Determination and Effect of Purpose of Loan. 27 Consumer Credit: Credits Extended Before December 1, 1946 27-28 Conversion of Non-Instalment Credit to Instalment Basis. 28 Preservation of Records. 28 Automobile Appraisal Guides. ... 28-30 Suit Regarding Removal of Bank Directors. ... 30-34 Foreign Funds Control—Treasury Department Releases. 34-35 Current Events 36-37 National Summary of Business Conditions. 38-39 Financial, Industrial, Commercial Statistics, U. S. (See p. 41 for list of tables) 41-93 International Financial Statistics (See p. 94 for list of tables). 94-111 Board of Governors and Staff; Open Market Committee and Staff; Federal Ad- visory Council 112 Senior Officers of Federal Reserve Banks; Managing Officers of Branches 113 Map of Federal Reserve Districts. -

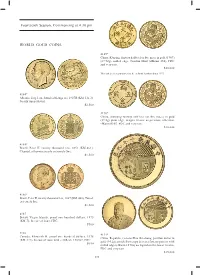

Fourteenth Session, Commencing at 4.30 Pm WORLD GOLD COINS

Fourteenth Session, Commencing at 4.30 pm WORLD GOLD COINS 4189* China, K'uping, fantasy half tael or fi ve mace in gold (1907) (27.92g), milled edge, Tientsin Mint (cfKann 154). FDC and very rare. $10,000 This and the next purported to be ex Spink London about 1973. 4184* Albania, Zog I, one hundred franga ari, 1927R (KM.11a.3). Nearly uncirculated. $2,500 4190* China, Sinkiang fantasy half tael (or fi ve mace) in gold (27.8g) plain edge, dragon reverse as previous, otherwise cfKann B107. FDC and very rare. $10,000 4185* Brazil, Peter II, twenty thousand reis, 1851 (KM.461). Cleaned, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne. $1,500 4186* Brazil, Peter II, twenty thousand reis, 1867 (KM.468). Toned, extremely fi ne. $1,000 4187 British Virgin Islands, proof one hundred dollars, 1975 (KM.7). In case of issue, FDC. $300 4188 4191* Canada, Elizabeth II, proof one hundred dollars, 1978 China, Republic, General Hsu Shi-chang, pavillon dollar in (KM.122). In case of issue with certifi cate 190767, FDC. gold (34.2g), struck from copy dies as a fantasy pattern with $650 milled edge (cfKann 1570a) no legend on the lower reverse. FDC and very rare. $15,000 484 4198* France, Napoleon Emperor, forty francs, 1811A (KM.696.1). Extremely fi ne. 4192* $600 China, Yuan Shih-kai, medallic gold fantasy dollar, not dated (1916), (41.76 g), signed L.Giorgi, plain edge, obv. military bust facing of Yuan Shih-kai with plumed cap and military uniform, rev. dragon to left, with sun above a fl eet of junks, commemorating inauguration of Hung Hsien regime, (KM. -

Metadata on the Exchange Rate Statistics

Metadata on the Exchange rate statistics Last updated 26 February 2021 Afghanistan Capital Kabul Central bank Da Afghanistan Bank Central bank's website http://www.centralbank.gov.af/ Currency Afghani ISO currency code AFN Subunits 100 puls Currency circulation Afghanistan Legacy currency Afghani Legacy currency's ISO currency AFA code Conversion rate 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new); with effect from 7 October 2002 Currency history 7 October 2002: Introduction of the new afghani (AFN); conversion rate: 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new) IMF membership Since 14 July 1955 Exchange rate arrangement 22 March 1963 - 1973: Pegged to the US dollar according to the IMF 1973 - 1981: Independently floating classification (as of end-April 1981 - 31 December 2001: Pegged to the US dollar 2019) 1 January 2002 - 29 April 2008: Managed floating with no predetermined path for the exchange rate 30 April 2008 - 5 September 2010: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 6 September 2010 - 31 March 2011: Stabilised arrangement (exchange rate within a narrow band without any political obligation) 1 April 2011 - 4 April 2017: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 5 April 2017 - 3 May 2018: Crawl-like arrangement (moving central rate with an annual minimum rate of change) Since 4 May 2018: Other managed arrangement Time series BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.M.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A01 -

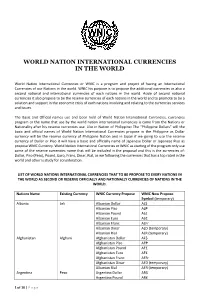

Propose Reserve Currency Table – for PDF Copy

WORLD NATION INTERNATIONAL CURRENCIES IN THE WORLD World Nation International Currencies or WNIC is a program and project of having an International Currencies of our Nations in the world. WNIC his purpose is to propose the additional currencies as also a second national and international currencies of each nations in the world. Aside of second national currencies it also propose to be the reserve currencies of each nations in the world and to promote to be a solution and support in the economic crisis of each nations involving and relating to the currencies services and issues. The Basic and Official names use and been hold of World Nation International Currencies, currencies program or the name that use by the world nation international currencies is came from the Nations or Nationality after his reserve currencies use. Like in Nation of Philippine: The “Philippine Dollars” will the basic and official names of World Nation International Currencies propose in the Philippine as Dollar currency will be the reserve currency of Philippine Nation and in Japan if we going to use the reserve currency of Dollar or Piso it will have a basic and officially name of Japanese Dollar or Japanese Piso as propose WNIC Currency. World Nation International Currencies or WNIC as starting of the program only use some of the reserve currencies name that will be included in the proposal and this is the currencies of: Dollar, Piso (Peso), Pound, Euro, Franc, Dinar, Rial, as we following the currencies that has a top rated in the world and other is study for consideration.