One Currency One? Country?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Handler, Heinz Working Paper The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area WIFO Working Papers, No. 446 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Handler, Heinz (2013) : The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area, WIFO Working Papers, No. 446, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/128970 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler 446/2013 The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler WIFO Working Papers, No. -

Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D

World Coins Session D Begins at 14:00 PST on Friday, January 20, 2017 1349. BAVARIA: Karl Albert, 1726-1745, AV ½ karolin, Munich mint, 1729, KM-406, Fr-230, bust right of king // crowned World Coins Madonna holding Christ child and coat-of-arms, much original luster, AU $600 - 800 Europe (continued) 1345. AUGSBURG: Udalschak, 1184-1202, AR bracteate (0.85g), Berger-2636/39, bust of the bishop, holding crozier & long cross, surrounded by 8 crescents, each filled with a lily, EF $120 - 160 This issue continued under Hartwig II, 1202-1208. 1350. BAVARIA: Karl Theodor, 1777-1799, AR thaler, 1799, KM-600.2, Dav-1966A, Madonna and Child, light reverse adjustment marks, somewhat prooflike, AU $250 - 300 1346. AUGSBURG: Hartmann II, 1250-1286, AR bracteate (0.75g), Berger-2644, enthroned bishop, with crozier & cross, EF $100 - 125 1351. BAVARIA: Maximilian II, 1848-1865, AR 2 thaler, 1856, KM-467, commemorating the Erection of the Monument of Maximilian II at Lindau, AU $400 - 500 1347. AUGSBURG: Anonymous, ca. 1290-1330, AR bracteate (0.56g), Berger-2656/61, head of the bishop, his hands raised before him, holding crozier and the bible, EF $100 - 125 1352. BAVARIA: Ludwig II, 1864-1886, AR thaler, 1865, KM-869, some hairlines, somewhat prooflike, UNC $175 - 225 1348. BAMBERG: Franz Ludwig, 1779-1795, AR thaler, 1795, KM-146, Dav-1939, Contribution thaler, somewhat prooflike, one-year type, made from the silver service of the Bishop, Choice AU $350 - 450 1353. BAVARIA: Otto, 1886-1913, AR 2 mark, 1888-D, KM-905, hairlined, nicely toned, EF $250 - 350 112 Stephen Album Rare Coins | Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D 1354. -

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

Historical Record of Monetary Unions: Lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov • Vol. 6 (55) •No. 2 - 2013 Series V: Economic Sciences HISTORICAL RECORD OF MONETARY UNIONS: LESSONS FOR THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION Ileana TACHE1 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to make a record of previous monetary unions and derive some useful lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union. Evaluating the political economy of the euro through the lens of history, with the help of comparative analysis, can contribute to better understanding the present stage of the EMU and its challenges. Even if the EU is a unique, sui generis, phenomenon, the analytical lessons learned from the historical cases could be applied to the contemporary situation of the euro. Key words: European Economic and Monetary Union, Gold Standard, USA monetary union, monetary unification of Italy, German Zollverein, Latin Monetary Union, Scandinavian Monetary Union. 1. Introduction The study is built on the main contributions Even if euro still appears like a novelty in of the literature in this field, such as Bordo the process of European construction and as and Jonung (1999), Bergman (1999), international currency, it was preceded by a Foreman-Peck (2005), McNamara (2011) few monetary unions on the continent and or de Vanssay (1999). outside of it. While much of the European The paper is organized as follows. The monetary project has indeed been of an next section is dedicated to the Gold ambition never seen in Europe before, the Standard, then the other monetary unions idea of bringing currencies together is far are discussed: USA monetary union after from new. -

Political Economy Thomas Plümper Version 2019

Political Economy Thomas Plümper Version 2019 Content 16.10.2019 Elections and Voting Behavior 23.10.2019 Party Competition and Electoral Systems 30.10.2019 Interest Groups, Lobbying and Reforms 06.11.2019 Business Cycle, Debt, Inflation 13.11.2019 Redistribution and Inequality 20.11.2019 Trade and Development 27.11.2019 Capital Flow, Exchange Rates and Currency Unions 04.12.2019 Tax Competition 11.12.2019 WU Matters: Natural Disasters 18.12.2019 Klausur 08.01.2020 Final Discussion Alternatives Number and Size of Nations, Political Integration and Brexit Terrorism and Anti-Terrorist Policies Migration and Asylum Else? Political Economy: Definitions Politicians neither love nor hate, interest, not sentiment, governs them. Earl of Chesterfield Political science has studied man’s behavior in the public arena; economics has studied man in the marketplace. Political science has often assumed that political man pursues the public interest. Economics has assumed that all men pursue their private interests. (…) But is this dichotomy valid? Dennis Muller Over its long lifetime, the phrase ‘political economy’ has had many meanings. For Adam Smith, political economy was the science of managing a nation’s resource as to generate wealth. For Marx, it was how the ownership of the means of production influenced historical processes. Weingast and Wittman A general definition is that political is the study of the interaction of politics and economics. Political economy begins with the nature of political decision-making and is concerned with how politics will affect economic choice in a society. Political economy begins with the observation that actual policies are often quite different from optimal policies. -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and Currencies in History from Earliest Times to the Euro

E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 3 Money Museum Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and currencies in history from earliest times to the euro Coins and maps from the MoneyMuseum with texts by Ursula Kampmann E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 4 All rights reserved Any form of reprint as well as the reproduction in television, radio, film, sound or picture storage media and the storage and dissemination in electronic media or use for talks, including extracts, are only permissible with the approval of the publisher. 1st edition ??? 2010 © MoneyMuseum by Sunflower Foundation Verena-Conzett-Strasse 7 P O Box 9628 C H-8036 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 242 76 54, Fax: +41 (0)44 242 76 86 Available for free at MoneyMuseum Hadlaubstrasse 106 C H-8006 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 350 73 80, Bureau +41 (0)44 242 76 54 For further information, please go to www.moneymuseum.com and to the Media page of www.sunflower.ch Cover and coin images by MoneyMuseum Coin images p. 56 above: Ph. Grierson, Münzen des Mittelalters (1976); p. 44 and 48 above: M. J. Price, Monnaies du Monde Entier (1983); p. 44 below: Staatliche Münzsammlung München, Vom Taler zum Dollar (1986); p. 56 below: Seaby, C oins of England and the United Kingdom (1998); p. 57: archive Deutsche Bundesbank; p. 60 above: H. Rittmann, Moderne Münzen (1974) Maps by Dagmar Pommerening, Berlin Typeset and produced by O esch Verlag, Zürich Printed and bound by ? Printed in G ermany E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 5 Contents The Publisher’s Foreword . -

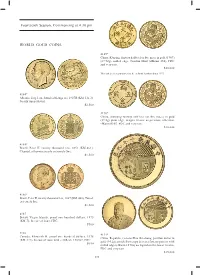

Fourteenth Session, Commencing at 4.30 Pm WORLD GOLD COINS

Fourteenth Session, Commencing at 4.30 pm WORLD GOLD COINS 4189* China, K'uping, fantasy half tael or fi ve mace in gold (1907) (27.92g), milled edge, Tientsin Mint (cfKann 154). FDC and very rare. $10,000 This and the next purported to be ex Spink London about 1973. 4184* Albania, Zog I, one hundred franga ari, 1927R (KM.11a.3). Nearly uncirculated. $2,500 4190* China, Sinkiang fantasy half tael (or fi ve mace) in gold (27.8g) plain edge, dragon reverse as previous, otherwise cfKann B107. FDC and very rare. $10,000 4185* Brazil, Peter II, twenty thousand reis, 1851 (KM.461). Cleaned, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne. $1,500 4186* Brazil, Peter II, twenty thousand reis, 1867 (KM.468). Toned, extremely fi ne. $1,000 4187 British Virgin Islands, proof one hundred dollars, 1975 (KM.7). In case of issue, FDC. $300 4188 4191* Canada, Elizabeth II, proof one hundred dollars, 1978 China, Republic, General Hsu Shi-chang, pavillon dollar in (KM.122). In case of issue with certifi cate 190767, FDC. gold (34.2g), struck from copy dies as a fantasy pattern with $650 milled edge (cfKann 1570a) no legend on the lower reverse. FDC and very rare. $15,000 484 4198* France, Napoleon Emperor, forty francs, 1811A (KM.696.1). Extremely fi ne. 4192* $600 China, Yuan Shih-kai, medallic gold fantasy dollar, not dated (1916), (41.76 g), signed L.Giorgi, plain edge, obv. military bust facing of Yuan Shih-kai with plumed cap and military uniform, rev. dragon to left, with sun above a fl eet of junks, commemorating inauguration of Hung Hsien regime, (KM. -

Ninth Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am WORLD SILVER & BRONZE

Ninth Session, Commencing at 11.30 am WORLD SILVER & BRONZE COINS 2786* Germany, Strassbourg, civic issue, 15th century, silver groschen, (3.55 grams), obv. lis within circular octagon frame, rev. cross, (Saurma 1965 [Pl.XXXII, 964], Boudeau 1344). Attractive grey tone, nearly extremely fi ne and rare. $200 Ex CNG. 2783* Germany, Altenburg, Friedrich I Barbarossa (1152-1190), silver pfennig as a bracteate, c.1185-1190. (0.95 grams), obv. seated ruler facing with orb surmounted by cross in his left hand and fl eur de lis in his right hand, line border, (cf.Kestner Hannover 2078 [p.256-7] attributed to Otto IV, Seega Collection 1905 [lot 530], cf.Riechmann [1925] Lobbecke Collection [lot 682], cf.Peus Sale 317 collection A 2787* [lot 852]). Large fl an, toned, very fi ne and rare, lot includes Germany, Ausburg, Ferdinand III, silver thaler, 1643 (KM.77; old 19th century ticket. Dav.5039). Toned, good very fi ne. $200 $300 Ex H.H. Kricheldorf Auction Sale 44, December 12, 1994 [lot 656]. 2788 Germany, Brandenburg in den Marken, Brandenburg - Prussia and Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector, (1640-1688), 1683 HS, six groschen (KM.429); Solms- Laubach, Christian August (1738-1784), County issue, ten kreuzer 1762 IIE/CRD, (KM.27). Last rare, very fi ne; good fi ne. (2) $100 2784* Germany, Altenburg, Heinrich VI (1190-1197), silver pfennig as a bracteate, c.1195. (0.945 grams), obv. seated ruler facing with orb surmounted by cross in his left hand and fl eur de lis in his right hand, line border, (cf.Kestner Hannover 2077 [p.256-7], Seega Collection 1905 [lot 535], cf.Riechmann [1925] Lobbecke Collection [lot 688], cf.Peus Sale 317 collection A [lot 855]). -

The Big Reset

REVISED s EDITION Willem s Middelkoop s TWarh on Golde and the Financial Endgame BIGs s RsE$EAUPTs The Big Reset The Big Reset War on Gold and the Financial Endgame ‘Revised and substantially enlarged edition’ Willem Middelkoop AUP Cover design: Studio Ron van Roon, Amsterdam Photo author: Corbino Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 027 3 e-isbn 978 90 4852 950 6 (pdf) e-isbn 978 90 4852 951 3 (ePub) nur 781 © Willem Middelkoop / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. To Moos and Misha In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods. -

Catalogue of a Large and Important Collection of Coins, Medals, Books

PUBLIC AUCTION SALE C ata logu e o f a La rge and I mpo rtant C o l le ct io n of COINS MEDA LS BOOK P R , , S , A PE MONEY CURIOS E , , tc . The P o ti s of Se a I ndividu als ff d Wi r per e ver l , O ere tho u t Res erve Inc lu ding : Large and Va rie d Lines of Un i ted States and Fo i n G o ld a nd Si l r C in of Al l S iz and A re g ve o s es ges , Hun re of i Tha e a nd M a Fi C C d ds S lver l rs ed ls , ne o lon ia l o ins and Pa Mon a 1 85 ] i er Do per ey , R re S lv l l ar , Handso m e Art M a B d l , Man o ks o n N umi matic Co l l c ti n G u n e s y o s s , e g , nery , n I ian , e tc . etc Au to a h Cu io t d s , , , gr p s , r s , e c . , Over 2250 Va i Lot To be r ed , S ld in Thre e Se ion s o ss s , On TH URSDAY FRI , DAY and SA T URDA Y ANUA Y J 30th , 3 I s t and F B UA Y l R , E R R s t , 1 9 1 9 ’ Comm nci om t h e ng Pr p ly Eac Day at o clo ck in the Afterno o n By THE ELDER co m CURIO co . -

Lissner Sale Slated a Highlight the Lissner Collection of World Coins Will of the Lissner Be Sold Aug

World Coin News • June 2014 World U.S. $4.99/Canada $5.99 Vol. 41, No. 6 • JUNE 2014 Lissner sale slated A highlight The Lissner collection of world coins will of the Lissner be sold Aug. 1-2 at the Chicago Marriott collection is O’Hare, just prior to the annual summer this Bolivia convention of the American Numismatic 1852 PTS FB Association in Rosemont, Ill. gold 8 escu- Valued at over $2 million, the collection dos, NGC will be sold by Classical Numismatic Group, MS-62, which Inc., of Lancaster, Pa., and London, England, is Lot 971300. and St. James’s Auctions Ltd. (Knightsbridge Lissner/Page 46 Paris dealer Prieur dies at age 58 By Mark Fox Our hobby lost one of its staunchest supporters Baldwin’s when Michel Prieur, the numismatist who literally set a record propelled French coin collecting into the 21st century, price when died March 18 of a sudden heart attack in Paris. His this Edward two blog postings on cgb.fr the same day signaled no VIII proof health issues. One was an appeal for information to sovereign sold locate the heirs of Joseph Daniel, author of Les jetons at auction for nearly des etats de Bretagne (1980). This was a title on jetons $870,000. Michel Prieur Prieur/Page 24 Künker reaches auction milestone The 250th auction sale of Fritz Rudolf Künker will feature The Masuren Collection and be conducted July Baldwin sets record 2, 2014 in Osnabrück, Germany. It is part of five days of sales to be held June 30-July with gold sovereign 4 that will offer over 5,000 lots.