The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Handler, Heinz Working Paper The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area WIFO Working Papers, No. 446 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Handler, Heinz (2013) : The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area, WIFO Working Papers, No. 446, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/128970 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler 446/2013 The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler WIFO Working Papers, No. -

MYNTAUKTION LÖRDAG 6 MAJ 2017 Svartensgatan 6, Stockholm

MYNTAUKTION LÖRDAG 6 MAJ 2017 Svartensgatan 6, Stockholm MYNTKOMPANIET Svartensgatan 6, 116 20 Stockholm, Sweden Tel. 08-640 09 78. Fax 08-643 22 38 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.myntkompaniet.se/auktion Förord Preface Välkommen till Myntkompaniets vårauktion 2017! Welcome to our Spring sale 2017! Det är med glädje som vi härmed presenterar vår tolfte It is with pleasure that we hereby present our twelfth coin myntauktion. auction. Sverige-avsnittet är denna gång extra fylligt med ett antal mynt som borde falla de flesta samlare i smaken. Bland ”topparna” The Swedish section this time is well represented with a number kan nämnas 1 daler 1559 i praktkvalitet, 1 daler 1592, det of coins that should appeal to most collectors. Some highlights begärliga typmyntet 8 mark 1608, 1 dukat 1701 och 1709, are 1 daler 1559 in superb quality, 1 daler 1592, the attractive samt ¼ dukat 1692. Typmyntet 2½ öre, ett av de vackraste 8 mark 1608, the stunning 2½ öre – one of the most beautiful 1 1 exemplaren av detta rara mynt, samt tre exemplar av /6 öre på specimens of this rare coin, three specimens of /6 öre on a en ej utstansad ten. Vi utbjuder även ovanligt många kastmynt planchet. We also offer an unusual number of largesse coins från 1620-talet och framåt. Bland de modernare mynten hittar from the 1620s onwards. Among the more modern coins we can vi ett ovanligt provmynt – 4 skilling banco 1844 med kungens find an unusual specimen coin – 4 skilling banco 1844 with the namnchiffer i stället för porträtt. -

Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D

World Coins Session D Begins at 14:00 PST on Friday, January 20, 2017 1349. BAVARIA: Karl Albert, 1726-1745, AV ½ karolin, Munich mint, 1729, KM-406, Fr-230, bust right of king // crowned World Coins Madonna holding Christ child and coat-of-arms, much original luster, AU $600 - 800 Europe (continued) 1345. AUGSBURG: Udalschak, 1184-1202, AR bracteate (0.85g), Berger-2636/39, bust of the bishop, holding crozier & long cross, surrounded by 8 crescents, each filled with a lily, EF $120 - 160 This issue continued under Hartwig II, 1202-1208. 1350. BAVARIA: Karl Theodor, 1777-1799, AR thaler, 1799, KM-600.2, Dav-1966A, Madonna and Child, light reverse adjustment marks, somewhat prooflike, AU $250 - 300 1346. AUGSBURG: Hartmann II, 1250-1286, AR bracteate (0.75g), Berger-2644, enthroned bishop, with crozier & cross, EF $100 - 125 1351. BAVARIA: Maximilian II, 1848-1865, AR 2 thaler, 1856, KM-467, commemorating the Erection of the Monument of Maximilian II at Lindau, AU $400 - 500 1347. AUGSBURG: Anonymous, ca. 1290-1330, AR bracteate (0.56g), Berger-2656/61, head of the bishop, his hands raised before him, holding crozier and the bible, EF $100 - 125 1352. BAVARIA: Ludwig II, 1864-1886, AR thaler, 1865, KM-869, some hairlines, somewhat prooflike, UNC $175 - 225 1348. BAMBERG: Franz Ludwig, 1779-1795, AR thaler, 1795, KM-146, Dav-1939, Contribution thaler, somewhat prooflike, one-year type, made from the silver service of the Bishop, Choice AU $350 - 450 1353. BAVARIA: Otto, 1886-1913, AR 2 mark, 1888-D, KM-905, hairlined, nicely toned, EF $250 - 350 112 Stephen Album Rare Coins | Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session D 1354. -

The Scandinavian Currency Union, 1873-1924

The Scandinavian Currency Union, 1873-1924 Studies in Monetary Integration and Disintegration t15~ STOCKHOLM SCHOOL 'lJi'L-9 OF ECONOMICS ,~## HANDELSHOGSKOLAN I STOCKHOLM BFI, The Economic Research Institute EFIMission EFI, the Economic Research Institute at the Stockholm School ofEconomics, is a scientific institution which works independently ofeconomic, political and sectional interests. It conducts theoretical and empirical research in management and economic sciences, including selected related disciplines. The Institute encourages and assists in the publication and distribution ofits research fmdings and is also involved in the doctoral education at the Stockholm School ofEconomics. EFI selects its projects based on the need for theoretical or practical development ofa research domain, on methodological interests, and on the generality ofa problem. Research Organization The research activities are organized in twenty Research Centers within eight Research Areas. Center Directors are professors at the Stockholm School ofEconomics. ORGANIZATIONAND MANAGEMENT Management and Organisation; (A) ProfSven-Erik Sjostrand Center for Ethics and Economics; (CEE) Adj ProfHans de Geer Center for Entrepreneurship and Business Creation; (E) ProfCarin Holmquist Public Management; (F) ProfNils Brunsson Infonnation Management; (I) ProfMats Lundeberg Center for People and Organization; (PMO) ProfJan Lowstedt Center for Innovation and Operations Management; (T) ProfChrister Karlsson ECONOMIC PSYCHOLOGY Center for Risk Research; (CFR) ProfLennart Sjoberg -

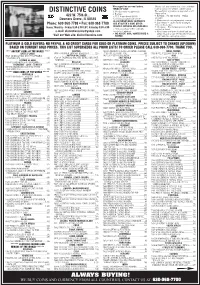

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

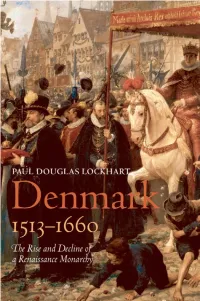

The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy

DENMARK, 1513−1660 This page intentionally left blank Denmark, 1513–1660 The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy PAUL DOUGLAS LOCKHART 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Paul Douglas Lockhart 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lockhart, Paul Douglas, 1963- Denmark, 1513–1660 : the rise and decline of a renaissance state / Paul Douglas Lockhart. -

Historical Record of Monetary Unions: Lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov • Vol. 6 (55) •No. 2 - 2013 Series V: Economic Sciences HISTORICAL RECORD OF MONETARY UNIONS: LESSONS FOR THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION Ileana TACHE1 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to make a record of previous monetary unions and derive some useful lessons for the European Economic and Monetary Union. Evaluating the political economy of the euro through the lens of history, with the help of comparative analysis, can contribute to better understanding the present stage of the EMU and its challenges. Even if the EU is a unique, sui generis, phenomenon, the analytical lessons learned from the historical cases could be applied to the contemporary situation of the euro. Key words: European Economic and Monetary Union, Gold Standard, USA monetary union, monetary unification of Italy, German Zollverein, Latin Monetary Union, Scandinavian Monetary Union. 1. Introduction The study is built on the main contributions Even if euro still appears like a novelty in of the literature in this field, such as Bordo the process of European construction and as and Jonung (1999), Bergman (1999), international currency, it was preceded by a Foreman-Peck (2005), McNamara (2011) few monetary unions on the continent and or de Vanssay (1999). outside of it. While much of the European The paper is organized as follows. The monetary project has indeed been of an next section is dedicated to the Gold ambition never seen in Europe before, the Standard, then the other monetary unions idea of bringing currencies together is far are discussed: USA monetary union after from new. -

Political Economy Thomas Plümper Version 2019

Political Economy Thomas Plümper Version 2019 Content 16.10.2019 Elections and Voting Behavior 23.10.2019 Party Competition and Electoral Systems 30.10.2019 Interest Groups, Lobbying and Reforms 06.11.2019 Business Cycle, Debt, Inflation 13.11.2019 Redistribution and Inequality 20.11.2019 Trade and Development 27.11.2019 Capital Flow, Exchange Rates and Currency Unions 04.12.2019 Tax Competition 11.12.2019 WU Matters: Natural Disasters 18.12.2019 Klausur 08.01.2020 Final Discussion Alternatives Number and Size of Nations, Political Integration and Brexit Terrorism and Anti-Terrorist Policies Migration and Asylum Else? Political Economy: Definitions Politicians neither love nor hate, interest, not sentiment, governs them. Earl of Chesterfield Political science has studied man’s behavior in the public arena; economics has studied man in the marketplace. Political science has often assumed that political man pursues the public interest. Economics has assumed that all men pursue their private interests. (…) But is this dichotomy valid? Dennis Muller Over its long lifetime, the phrase ‘political economy’ has had many meanings. For Adam Smith, political economy was the science of managing a nation’s resource as to generate wealth. For Marx, it was how the ownership of the means of production influenced historical processes. Weingast and Wittman A general definition is that political is the study of the interaction of politics and economics. Political economy begins with the nature of political decision-making and is concerned with how politics will affect economic choice in a society. Political economy begins with the observation that actual policies are often quite different from optimal policies. -

Sweden in the Seventeenth Century

Sweden in the Seventeenth Century Paul Douglas Lockhart Sweden in the Seventeenth Century European History in Perspective General Editor: Jeremy Black Benjamin Arnold Medieval Germany, 500–1300 Ronald Asch The Thirty Years’ War Christopher Bartlett Peace, War and the European Powers, 1814–1914 Robert Bireley The Refashioning of Catholicism, 1450–1700 Donna Bohanan Crown and Nobility in Early Modern France Arden Bucholz Moltke and the German Wars, 1864–1871 Patricia Clavin The Great Depression, 1929–1939 Paula Sutter Fichtner The Habsburg Monarchy, 1490–1848 Mark Galeotti Gorbachev and his Revolution David Gates Warfare in the Nineteenth Century Alexander Grab Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe Martin P. Johnson The Dreyfus Affair Paul Douglas Lockhart Sweden is the Seventeenth Century Peter Musgrave The Early Modern European Economy J.L. Price The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century A.W. Purdue The Second World War Christopher Read The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System Francisco J. Romero-Salvado Twentieth-Century Spain Matthew S. Seligmann and Roderick R. McLean Germany from Reich to Republic, 1871–1918 Brendan Simms The Struggle for Mastery in Germany, 1779–1850 David Sturdy Louis XIV David J. Sturdy Richelieu and Mazarin Hunt Tooley The Western Front Peter Waldron The End of Imperial Russia, 1855–1917 Peter G. Wallace The Long European Reformation James D. White Lenin Patrick Williams Philip II European History in Perspective Series Standing Order ISBN 0–333–71694–9 hardcover ISBN 0–333–69336–1 paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

A Long Term Perspective on the Euro

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A LONG TERM PERSPECTIVE ON THE EURO Michael D. Bordo Harold James Working Paper 13815 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13815 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2008 Paper prepared for the conference "Ten Years After the Euro", DGECFIN Brussels, Belgium, November 26-27, 2007. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Michael D. Bordo and Harold James. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Long Term Perspective on the Euro Michael D. Bordo and Harold James NBER Working Paper No. 13815 February 2008 JEL No. F02,F33,N20 ABSTRACT This study grounds the establishment of EMU and the euro in the context of the history of international monetary cooperation and of monetary unions, above all in the U.S., Germany and Italy. The purpose of national monetary unions was to reduce transactions costs of multiple currencies and thereby facilitate commerce; to reduce exchange rate volatility; and to prevent wasteful competition for seigniorage. By contrast, supranational unions, such as the Latin Monetary Union or the Scandinavian Currency Union were conducted in the broader setting of an international monetary order, the gold standard. -

Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and Currencies in History from Earliest Times to the Euro

E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 3 Money Museum Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and currencies in history from earliest times to the euro Coins and maps from the MoneyMuseum with texts by Ursula Kampmann E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 4 All rights reserved Any form of reprint as well as the reproduction in television, radio, film, sound or picture storage media and the storage and dissemination in electronic media or use for talks, including extracts, are only permissible with the approval of the publisher. 1st edition ??? 2010 © MoneyMuseum by Sunflower Foundation Verena-Conzett-Strasse 7 P O Box 9628 C H-8036 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 242 76 54, Fax: +41 (0)44 242 76 86 Available for free at MoneyMuseum Hadlaubstrasse 106 C H-8006 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 350 73 80, Bureau +41 (0)44 242 76 54 For further information, please go to www.moneymuseum.com and to the Media page of www.sunflower.ch Cover and coin images by MoneyMuseum Coin images p. 56 above: Ph. Grierson, Münzen des Mittelalters (1976); p. 44 and 48 above: M. J. Price, Monnaies du Monde Entier (1983); p. 44 below: Staatliche Münzsammlung München, Vom Taler zum Dollar (1986); p. 56 below: Seaby, C oins of England and the United Kingdom (1998); p. 57: archive Deutsche Bundesbank; p. 60 above: H. Rittmann, Moderne Münzen (1974) Maps by Dagmar Pommerening, Berlin Typeset and produced by O esch Verlag, Zürich Printed and bound by ? Printed in G ermany E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 5 Contents The Publisher’s Foreword .