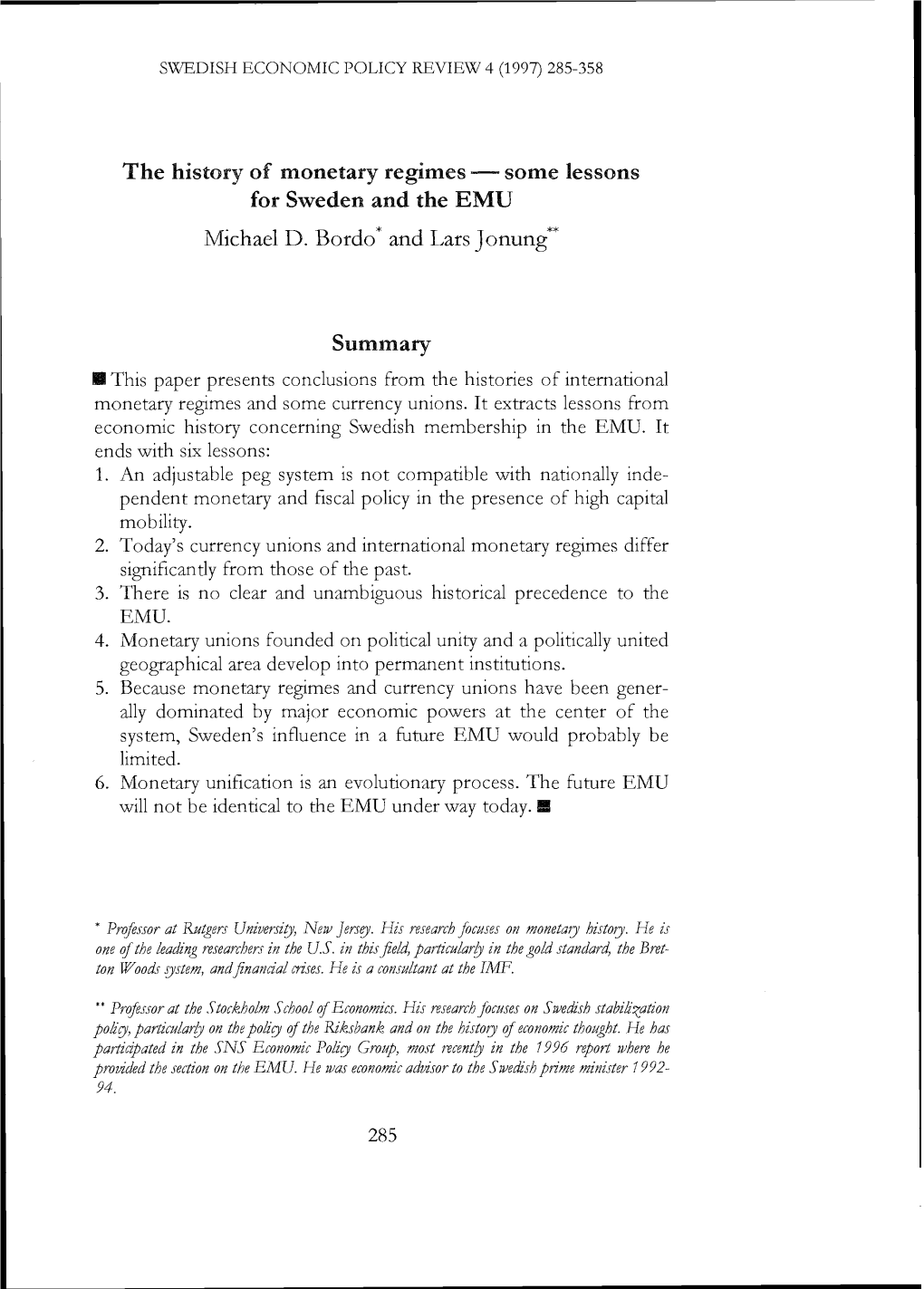

The History of Monetary Regimes - Some Lessons for Sweden and the EMU Michael D.Rordo* and Lars Jonung'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Handler, Heinz Working Paper The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area WIFO Working Papers, No. 446 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Handler, Heinz (2013) : The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area, WIFO Working Papers, No. 446, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/128970 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler 446/2013 The Eurozone: Piecemeal Approach to an Optimum Currency Area Heinz Handler WIFO Working Papers, No. -

MYNTAUKTION LÖRDAG 6 MAJ 2017 Svartensgatan 6, Stockholm

MYNTAUKTION LÖRDAG 6 MAJ 2017 Svartensgatan 6, Stockholm MYNTKOMPANIET Svartensgatan 6, 116 20 Stockholm, Sweden Tel. 08-640 09 78. Fax 08-643 22 38 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.myntkompaniet.se/auktion Förord Preface Välkommen till Myntkompaniets vårauktion 2017! Welcome to our Spring sale 2017! Det är med glädje som vi härmed presenterar vår tolfte It is with pleasure that we hereby present our twelfth coin myntauktion. auction. Sverige-avsnittet är denna gång extra fylligt med ett antal mynt som borde falla de flesta samlare i smaken. Bland ”topparna” The Swedish section this time is well represented with a number kan nämnas 1 daler 1559 i praktkvalitet, 1 daler 1592, det of coins that should appeal to most collectors. Some highlights begärliga typmyntet 8 mark 1608, 1 dukat 1701 och 1709, are 1 daler 1559 in superb quality, 1 daler 1592, the attractive samt ¼ dukat 1692. Typmyntet 2½ öre, ett av de vackraste 8 mark 1608, the stunning 2½ öre – one of the most beautiful 1 1 exemplaren av detta rara mynt, samt tre exemplar av /6 öre på specimens of this rare coin, three specimens of /6 öre on a en ej utstansad ten. Vi utbjuder även ovanligt många kastmynt planchet. We also offer an unusual number of largesse coins från 1620-talet och framåt. Bland de modernare mynten hittar from the 1620s onwards. Among the more modern coins we can vi ett ovanligt provmynt – 4 skilling banco 1844 med kungens find an unusual specimen coin – 4 skilling banco 1844 with the namnchiffer i stället för porträtt. -

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913

THE FEDERAL RESERVE ACT OF 1913 HISTORY AND DIGEST by V. GILMORE IDEN PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL BANK NEWS PHILADELPHIA Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Copyright, 1914 by Ccrtttiois Bator Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis History of Federal Reserve Act History N MONDAY, October 21, 1907, the Na O tional Bank of Commerce of New York City announced its refusal to clear for the Knickerbocker Trust Company of the same city. The trust company had deposits amounting to $62,000,000. The next day, following a run of three hours, the Knickerbocker Trust Company paid out $8,000,000 and then suspended. One immediate result was that banks, acting independently, held on tight to the cash they had in their vaults, and money went to a premium. Ac cording to the experts who investigated the situation, this panic was purely a bankers’ panic and due entirely to our system of banking, which bases the protection of the financial solidity of the country upon the individual reserves of banks. In the case of a stress, such as in 1907, the banks fail to act as a whole, their first consideration being the protec tion of their own reserves. PAGE 5 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis History of Federal Reserve Act The conditions surrounding previous panics were entirely different. -

Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Variation in the Paper Monies Issued by the American Colonies from 1690 to 1775

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS PAPER MONEY JUST PAPER MONEY? EXPERIMENTATION AND VARIATION IN THE PAPER MONIES ISSUED BY THE AMERICAN COLONIES FROM 1690 TO 1775 Farley Grubb Working Paper 17997 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17997 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2012 Previously circulated as 'Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Local Variation in the Fiat Paper Monies Issued by the Colonial Governments of British North America, 1690-1775: Part I." A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the Conference on "De-Teleologising History of Money and Its Theory," Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research–Project 22330102, University of Tokyo, 14-16 February 2012. The author thanks the participants of this conference and Akinobu Kuroda for helpful comments. Tracy McQueen provided editorial assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Farley Grubb. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Variation in the Paper Monies Issued by the American Colonies from 1690 to 1775 Farley Grubb NBER Working Paper No. 17997 April 2012, Revised April 2015 JEL No. -

Report on the Legal Protection of Banknotes in the European Union Member States

ECB EZB EKT BCE EKP REPORT ON THE LEGAL PROTECTION OF BANKNOTES IN THE EUROPEAN UNION MEMBER STATES November 1999 REPORT ON THE LEGAL PROTECTION OF BANKNOTES IN THE EUROPEAN UNION MEMBER STATES November 1999 © European Central Bank, 1999 Address Kaiserstrasse 29 D-60311 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 16 03 19 D-60066 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone +49 69 1344 0 Internet http://www.ecb.int Fax +49 69 1344 6000 Telex 411 144 ecb d All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank. ISBN 92-9181-051-7 2 ECB Report on the legal protection of banknotes • November 1999 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 I. LEGAL PROTECTION OF EURO BANKNOTES 7 A. THE CRIMINAL APPROACH: COUNTERFEITING 7 1. The legal situation in the Member States 7 2. The desired legal situation 9 3. The risk of increased counterfeit activity 11 4. The possibilities of prevention – co-operation and co-ordination 12 5. The harmonisation of sanctions 18 6. The detention of counterfeit banknotes 18 B. THE CIVIL APPROACH: COPYRIGHT PROTECTION (COMPLEMENTARY TOOLS AND SETTING CRITERIA FOR LEGAL REPRODUCTIONS) 20 1. Copyright protection for euro banknotes 20 2. The use of the © sign on euro banknotes 22 3. The enforcement of copyright 23 4. The reproduction of euro banknotes 24 C. THE MATERIAL APPROACH: ANTI-COPYING DEVICES FOR REPRODUCTION EQUIPMENT 26 II. LEGAL ASPECTS OF FIDUCIARY CIRCULATION 28 A. -

The Scandinavian Currency Union, 1873-1924

The Scandinavian Currency Union, 1873-1924 Studies in Monetary Integration and Disintegration t15~ STOCKHOLM SCHOOL 'lJi'L-9 OF ECONOMICS ,~## HANDELSHOGSKOLAN I STOCKHOLM BFI, The Economic Research Institute EFIMission EFI, the Economic Research Institute at the Stockholm School ofEconomics, is a scientific institution which works independently ofeconomic, political and sectional interests. It conducts theoretical and empirical research in management and economic sciences, including selected related disciplines. The Institute encourages and assists in the publication and distribution ofits research fmdings and is also involved in the doctoral education at the Stockholm School ofEconomics. EFI selects its projects based on the need for theoretical or practical development ofa research domain, on methodological interests, and on the generality ofa problem. Research Organization The research activities are organized in twenty Research Centers within eight Research Areas. Center Directors are professors at the Stockholm School ofEconomics. ORGANIZATIONAND MANAGEMENT Management and Organisation; (A) ProfSven-Erik Sjostrand Center for Ethics and Economics; (CEE) Adj ProfHans de Geer Center for Entrepreneurship and Business Creation; (E) ProfCarin Holmquist Public Management; (F) ProfNils Brunsson Infonnation Management; (I) ProfMats Lundeberg Center for People and Organization; (PMO) ProfJan Lowstedt Center for Innovation and Operations Management; (T) ProfChrister Karlsson ECONOMIC PSYCHOLOGY Center for Risk Research; (CFR) ProfLennart Sjoberg -

OIG-10-024 Audit of the Office of Comptroller of The

Audit Report OIG-10-024 Audit of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s Fiscal Years 2009 and 2008 Financial Statements December 22, 2009 Office of Inspector General Department of the Treasury DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20220 OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL December 22, 2009 MEMORANDUM FOR JOHN C. DUGAN COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY FROM: Michael Fitzgerald Director, Financial Audits SUBJECT: Audit of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s Fiscal Years 2009 and 2008 Financial Statements I am pleased to transmit the attached audited Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) financial statements for fiscal years 2009 and 2008. Under a contract monitored by the Office of Inspector General, GKA, P.C. (GKA), an independent certified public accounting firm, performed an audit of the financial statements of OCC as of September 30, 2009 and 2008 and for the years then ended. The contract required that the audit be performed in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards; applicable provisions of Office of Management and Budget Bulletin No. 07-04, Audit Requirements for Federal Financial Statements, as amended; and the GAO/PCIE Financial Audit Manual. The following reports, prepared by GKA, are incorporated in the attachment: • Independent Auditor’s Report on Financial Statements; • Independent Auditor’s Report on Internal Control over Financial Reporting; and • Independent Auditor’s Report on Compliance with Laws and Regulations In its audit of OCC’s financial statements, GKA found: • that the financial statements were fairly presented, in all material respects, in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America, • no matters involving internal control and its operations that are considered material weaknesses, and • no instances of reportable noncompliance with laws and regulations tested. -

Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America

Number 2015-06 ECONOMIC COMMENTARY May 13, 2015 Paper Money and Infl ation in Colonial America Owen F. Humpage Infl ation is often thought to be the result of excessive money creation—too many dollars chasing too few goods. While in principle this is true, in practice there can be a lot of leeway, so long as trust in the monetary authority’s ability to keep things under control remains high. The American colonists’ experience with paper money illustrates how and why this is so and offers lessons for the modern day. Money is a societal invention that reduces the costs of The Usefulness of Money engaging in economic exchange. By so doing, money allows Money reduces the cost of engaging in economic exchange individuals to specialize in what they do best, and specializa- primarily by solving the double-coincidence-of-wants prob- tion—as Adam Smith famously pointed out—increases a lem. Under barter, if you have an item to trade, you must nation’s standard of living. Absent money, we would all fi rst fi nd people who want it and then fi nd one among them have to barter, which is time consuming and wasteful. who has exactly what you desire. That is diffi cult enough, but suppose you needed that specifi c thing today and had If money is to do its job well, it must maintain a stable value nothing to exchange until later. Making things always re- in terms of the goods and services that it buys. Traditional- quires access to the goods necessary for their production ly, monies have kept their purchasing power by being made before the fi nal good is ready, but pure barter requires that of precious metals—notably gold, silver, and copper—that receipts and outlays occur at the same time. -

Davis S Dissertation 2010.Pdf

The Trend Towards The Debasement Of American Currency A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Steven Davis Master of Science Stanford University, 2003 Master of Science University of Durham, 2002 Bachelor of Science University of Pennsylvania, 2001 Director: Dr. Richard Wagner, Professor Department of Economics Fall Semester 2010 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2010 by Steven Davis All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Richard Wagner, Robin Hanson, and John Crockett for their insight, feedback, and flexibility in their positions on my dissertation committee. Additional thanks to Professor Wagner for his guidance in helping me customize my academic program here at George Mason. I would also like to thank Mary Jackson for her amazing responsiveness to all of my questions and her constant supply of Krackel candy bars. Thanks to Professor “Doc” Bennett for being a great “RA-employer” and helping me optimize my Scantron-grading technique. Thanks to the Economics Department for greatly assisting my studies by awarding me the Dunn Fellowship, as well as providing a great environment for economic study. Thanks to my Mom and Dad for both their support and their implicit contribution to the Allen Davis game. Finally, thanks to the unknown chef of the great brownies available in the small Enterprise Hall cafeteria. Hopefully, they will one day become a topping at Mr. Yogato or at its successor, Little Yohai. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................ vi ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. viii Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................. -

The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy

DENMARK, 1513−1660 This page intentionally left blank Denmark, 1513–1660 The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy PAUL DOUGLAS LOCKHART 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Paul Douglas Lockhart 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lockhart, Paul Douglas, 1963- Denmark, 1513–1660 : the rise and decline of a renaissance state / Paul Douglas Lockhart. -

Sweden in the Seventeenth Century

Sweden in the Seventeenth Century Paul Douglas Lockhart Sweden in the Seventeenth Century European History in Perspective General Editor: Jeremy Black Benjamin Arnold Medieval Germany, 500–1300 Ronald Asch The Thirty Years’ War Christopher Bartlett Peace, War and the European Powers, 1814–1914 Robert Bireley The Refashioning of Catholicism, 1450–1700 Donna Bohanan Crown and Nobility in Early Modern France Arden Bucholz Moltke and the German Wars, 1864–1871 Patricia Clavin The Great Depression, 1929–1939 Paula Sutter Fichtner The Habsburg Monarchy, 1490–1848 Mark Galeotti Gorbachev and his Revolution David Gates Warfare in the Nineteenth Century Alexander Grab Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe Martin P. Johnson The Dreyfus Affair Paul Douglas Lockhart Sweden is the Seventeenth Century Peter Musgrave The Early Modern European Economy J.L. Price The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century A.W. Purdue The Second World War Christopher Read The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System Francisco J. Romero-Salvado Twentieth-Century Spain Matthew S. Seligmann and Roderick R. McLean Germany from Reich to Republic, 1871–1918 Brendan Simms The Struggle for Mastery in Germany, 1779–1850 David Sturdy Louis XIV David J. Sturdy Richelieu and Mazarin Hunt Tooley The Western Front Peter Waldron The End of Imperial Russia, 1855–1917 Peter G. Wallace The Long European Reformation James D. White Lenin Patrick Williams Philip II European History in Perspective Series Standing Order ISBN 0–333–71694–9 hardcover ISBN 0–333–69336–1 paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Statement on Hr 1098, the Free Competition in Currency Act of 2011 September 13, 2011 ______

STATEMENT ON HR 1098, THE FREE COMPETITION IN CURRENCY ACT OF 2011 SEPTEMBER 13, 2011 _____________________ Lawrence H. White Professor of Economics, George Mason University House Committee on Financial Services Subcommittee on Domestic Monetary Policy and Technology Chairman Paul, Ranking Member Clay, and members of the subcommittee: Thank you for the opportunity to discuss my views on HR 1098, the Free Competition in Currency Act of 2011 (hereafter “the Act”). As an economist specializing in monetary systems I have studied and written for many years about the role of free competition in currency. Indeed the second book of my three books on the topic, published in 1989 by New York University Press, was entitled Competition and Currency. THE BENEFITS OF CURRENCY COMPETITION It is widely understood that competition among private enterprises gives us technological improvements in all kinds of products, delivering higher quality at lower cost. For example, the competition of FedEx and UPS with the U.S. Postal Service in package delivery has been of great benefit to American consumers. Currency users also benefits from competition. My research indicates that currency has been better provided by competing private enterprises than by government monopoly. For example, private gold and silver mints during the American gold rushes provided trustworthy coins until they were suppressed by legislation. Scientific appraisals have found that the privately minted coins were produced even more precisely than the coins of the U.S. Mint. Private bank-issued currency was the most popular form of money around the world until government-sponsored central banks, with few exceptions, gained exclusive note-issuing privileges.