Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Mentions

SPECIAL MENTIONS The following matters of Public Importance were laid on the Table with the permission of the Chair during the Session: — Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. *1. 21-08- Shri Lalit Kishore Need to release funds for 2007 Chaturvedi renovation of National Highways in Rajasthan. 2. -do- Shri Motilal Vora Concern over the shortage of seeds with Chhattisgarh Seed Development Corporation. 3. -do- Shrimati Brinda Concern over import of wheat at a Karat high price. 4. -do- Shri Abu Asim Azmi Concern over delay in Liberhan 0-01 Commission Report. 5. -do- Shri Santosh Demand to ban toxic toys. Bagrodia 6. -do- Shrimati N.P. Durga Need to appoint at least two teachers in every school in the Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. country. 7. -do- Shri Dharam Pal Demand to make strict laws to curb Sabharwal smear campaign by Media. 8. 21-08- Shri Thennala G. Demand to take measures to check 2007 Balakrishna Pillai outbreak of Chikunguniya and Dengue fever in Kerala. 9. -do- Shri Pyarelal Concern over unprecedented Khandelwal increase in the prices of medicines. 10. -do- Shri Jai Parkash Need to take advance measures to Aggarwal protect telecom and other services from probable dangers of strong solar rays. 11. -do- Shri Saman Pathak Demand to improve the condition of National Highways in the North- Eastern region. 12. -do- Shri Moinul Hassan Demand to re-constitute Jute 0-01 Advisory Board and Jute Development Council. Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. -

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

PESA-DP-Hyderabad-Sindh.Pdf

Rani Bagh, Hyderabad “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Hyderabad August 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader de velopment programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

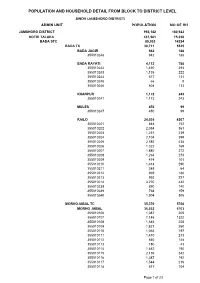

Jamshoro Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAMSHORO DISTRICT 993,142 180,922 KOTRI TALUKA 437,561 75,038 BADA STC 85,033 14234 BADA TC 30,711 5525 BADA JAGIR 942 188 355010248 942 188 BADA RAYATI 4,112 788 355010242 1,430 294 355010243 1,135 222 355010244 677 131 355010245 66 8 355010246 804 133 KHANPUR 1,173 243 355010241 1,173 243 MULES 450 99 355010247 450 99 RAILO 24,034 4207 355010201 844 152 355010202 2,054 361 355010203 1,251 239 355010204 2,104 399 355010205 2,585 438 355010206 1,022 169 355010207 1,880 272 355010208 1,264 273 355010209 474 101 355010210 1,414 290 355010211 348 64 355010212 969 186 355010213 993 227 355010214 3,270 432 355010238 890 140 355010239 768 159 355010240 1,904 305 MORHOJABAL TC 35,370 5768 MORHO JABAL 35,032 5703 355010106 1,087 205 355010107 7,146 1322 355010108 1,646 228 355010109 1,821 260 355010110 1,065 197 355010111 1,410 213 355010112 840 148 355010113 180 43 355010114 1,462 190 355010115 2,136 342 355010116 1,387 192 355010117 1,544 216 355010118 617 104 Page 1 of 23 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 355010119 79 15 355010120 3,665 538 355010121 951 129 355010122 2,161 343 355010123 2,169 355 355010124 1,468 261 355010125 2,198 402 TARBAND 338 65 355010126 338 65 PETARO TC 18,952 2941 ANDHEJI-KASI 1,541 292 355010306 1,541 292 BELO GHUGH 665 134 355010311 665 134 MANJHO JAGIR 659 123 355010307 659 123 MANJHO RAYATI 1,619 306 355010310 1,619 -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

Crimeindelhi.Pdf

CRIME IN DELHI 2018 as against 2,23,077 in 2017. The yardstick of crime per lakh of population is generally used worldwide to compare The social churning is quite evident in the crime scene of the crime rate. Total IPC crime per lakh of population was 1289 capital. The Delhi Police has been closely monitoring the ever- crimes during the year 2018, in comparison to 1244 such changing modus operandi being adopted by criminals and crimes during last year. adapting itself to meet these new challenges head-on. The year 2018 saw a heavy thrust on modernization coupled with unrelenting efforts to curb crime. Here too, there was a heavy TOTAL IPC CRIME mix of the state-of-the-art technology with basic policing. The (per lakh of population) police maintained a delicate balance between the two and this 1500 was evident in the major heinous cases worked out this year. 1243.90 1289.36 Along with modern investigative techniques, traditional beat- 1200 1137.21 level inputs played a major role in tackling crime and also in 900 its prevention and detection. 600 Some of the important factors impacting crime in Delhi are 300 the size and heterogeneous nature of its population; disparities in income; unemployment/ under employment, consumerism/ 0 materialism and socio-economic imbalances; unplanned 2016 2017 2018 urbanization with a substantial population living in jhuggi- jhopri/kachchi colonies and a nagging lack of civic amenities therein; proximity in location of colonies of the affluent and the under-privileged; impact of the mass media and the umpteen TOTAL IPC advertisements which sell a life-style that many want but cannot afford; a fast-paced life that breeds a general proclivity 250000 223077 236476 towards impatience; intolerance and high-handedness; urban 199107 anonymity and slack family control; easy accessibility/means 200000 of escape to criminal elements from across the borders/extended 150000 hinterland in the NCR region etc. -

The Marked Reduction of the Indus River Flow

The marked reduction of the Indus river flow downstream from the Kotry barrage: can the mangrove ecosystems of Pakistan survive in the resulting hypersaline environment? Item Type article Authors Ahmed, S.I. Download date 01/10/2021 19:37:14 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31900 Pakistan Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol.1(2), 145-153, 1992. REVIEW ARTICLE THE MARKED REDUCTION OF THE INDUS RIVER FLOW DOWNSTREAM FROM THE KOTRI BARRAGE: CAN THE MANGROVE ECOSYSTEMS OF PAKISTAN· SURVIVE IN THE RESULTING HYPERSALINE ENVIRONMENT? Saiyed I. Ahmed School of Oceanography, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, U.SA. APPLICATION OF KNOWLEDGE ,OF MANGROVE ECOSYSTEMS FROM AROUND THE WORLD TO THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE PRESENT STATUS OF MANGROVES OF PAKISTAN. The global inventory of obligate mangroves consists of 54 species belonging to 20 genera in 16 families and are estimated to occupy about 23 million hectares of shel tered coastal intertidal land (Tomlinson, 1986; Lugo and Snedaker, 1974; Chapman, 1975, 1976). These are regarded as 11 obligate11 mangroves as they are 11 restricted11 to coastal saline intertidal environments compared to 11 facultative 11 mangroves which may develop in non-coastal environments. In a general classification scheme basically two groups of mangroves can be identified: (a) the Eastern Group: mangroves on the coasts of Indian and Western Pacific Oceans, (b) the Western Group: Those on the coasts of the Americas, West Indies and West Africa. Generally speaking, the Eastern Group of mangroves is richer in species diversity with mangroves in India and southeast Asia exhibiting species diversity of > 20 with generally healthy and luxurious plant growth. -

Sindh Fact Sheet Final Version

FACTS & FIGURES October- December 2011 Sindh The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been active in Pakistan since 1948, with a permanent presence since 1982. In the province of Sindh, the ICRC provides support to First Aid training conducted by the Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) and hosts seminars on emergency response for medical doctors. It provides training in International Humanitarian Law (IHL) for the Pakistan Armed Forces and promotes IHL in civil society through educational institutions. It contributes to the training of the Police, teaching human right norms governing the use of force in law enforcement. It carries out prison visits, supporting the authorities' efforts to comply with international norms and standards and helps separated family members to restore and maintain contact with each other. When the devastating floods hit Sindh in 2010, the ICRC set up a logistic base in Karachi and launched a large-scale relief operation in northern Sindh in partnership with the PRCS. Throughout 2011, the ICRC continued to assist the population in their efforts to recover from the consequences of the 2010 floods and supported the response of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in the areas affected by the floods in 2011. Standing by victims of floods The ICRC has completed the renovation of the Sheranpur Basic Healthcare Unit (BHU), while the renovation of Mohammad Pur BHU building as well as construction of its During the final quarter of 2011, the ICRC has assisted boundary wall will be completed early January 2012. 30,419 flood-affected families, comprising about 212,000 people, in a third distribution round of food and essential The renovation of the Garhi Khairo Taluka Hospital is household items in six Union Councils namely Mohammad ongoing and 70% of the structural works has been Pur, Allan Pur, Miran Pur, Garhi Khairo, Allahabad and completed. -

Bonded Labour in Agriculture: a Rapid Assessment in Sindh and Balochistan, Pakistan

InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration on Fundamental Principles WORK IN FREEDOM and Rights at Work International Labour Office Bonded labour r in agriculture: e a rapid assessment p in Sindh and Balochistan, a Pakistan P Maliha H. Hussein g Abdul Razzaq Saleemi Saira Malik Shazreh Hussain n i k r Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour o DECLARATION/WP/26/2004 ISBN 92-2-115484-X W WP. 26 Working Paper Bonded labour in agriculture: a rapid assessment in Sindh and Balochistan, Pakistan by Maliha H. Hussein Abdul Razzaq Saleemi Saira Malik Shazreh Hussain International Labour Office Geneva March 2004 Foreword In June 1998 the International Labour Conference adopted a Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up that obligates member States to respect, promote and realize freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, the effective abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.1 The InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration is responsible for the reporting processes and technical cooperation activities associated with the Declaration; and it carries out awareness raising, advocacy and research – of which this Working Paper is an example. Working Papers are meant to stimulate discussion of the questions covered by the Declaration. They express the views of the author, which are not necessarily those of the ILO. This Working Paper is one of a series of Rapid Assessments of bonded labour in Pakistan, each of which examines a different economic sector. -

Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No

FINAL REPORT Mid-Term Evaluation /' " / " kku / Kondioro k I;sDDHH1 (Koo1,, * Nowbshoh On$ Hyderobcd Bulei Pt.ochi 7 godin Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No. 391-0480 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Islamabad, Pakistan IOC PDC-0249-1-00-0019-00 * Delivery Order No. 23 prepared by DE LEUWx CATHER INTERNATIONAL LIMITED May 26, 1993 Table of Contents Section Pafle Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables and Figures iv List of Abbieviations, Acronyms vi Basic Project Identification Data Sheet ix AID Evaluation Summary x Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-1 Chapter 2 - Background 2-1 Chapter 3 - Road Maintenance 3-1 Chapter 4 - Road Rehabilitation 4-1 Chapter 5 - Training Programs 5-1 Chapter 6 - District Revenue Sources 6-1 Appendices: - A. Work Plan for Mid-term Evaluation A-1 - B. Principal Officers Interviewed B-1 - C. Bibliography of Documents C-1 - D. Comparison of Resources and Outputs for Maintenance of District Roads in Sindh D-1 - E. Paved Road System Inventories: 6/89 & 4/93 E-1 - F. Cost Benefit Evaluations - Districts F-1 - ii Appendices (cont'd.): - G. "RRM" Road Rehabilitation Projects in SINDH PROVINCE: F.Y.'s 1989-90; 1991-92; 1992-93 G-1 - H. Proposed Training Schedule for Initial Phase of CCSC Contract (1989 - 1991) H-1 - 1. Maintenance Manual for District Roads in Sindh - (Revised) August 1992 I-1 - J. Model Maintenance Contract for District Roads in Sindh - August 1992 J-1 - K. Sindh Local Government and Rural Development Academy (SLGRDA) - Tandojam K-1 - L. -

Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program

SFG3075 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Public Disclosure Authorized Development Department, Government of Sindh Final Report December 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Final Report Executive Summary Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, GOS and Agriculture Department GOS with grant assistance from DFID funded multi donor trust fund for Nutrition in Pakistan are planning to undertake Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition (MSAN) Project. ESMF Consultant1 has been commissioned by Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning to fulfil World Bank Operational Policies and to prepare “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for MSAN Project” at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA during project execution. The project has two components under Inter Sectoral Nutrition Strategy of Sindh (INSS), i) the sanitation component of the project aligns with the Government of Sindh’s sanitation intervention known as Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) in 13 districts in the province and aims to increase the number of ODF villages through certification while ii) the agriculture for nutrition (A4N) component includes pilot targeting beneficiaries for household production and consumption of healthier foods through increased household food production in 20 Union Councils of 4 districts. Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) This component of the project will be sponsored by Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, Sindh and executed by Local Government Department (LGD) through NGOs working for the Inter-sectoral Nutrition Support Program.