The Toarcian–Bathonian Succession of the Antsiranana Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Substantial Vegetation Response to Early Jurassic Global Warming with Impacts on Oceanic Anoxia

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0349-z Substantial vegetation response to Early Jurassic global warming with impacts on oceanic anoxia Sam M. Slater 1*, Richard J. Twitchett2, Silvia Danise3 and Vivi Vajda 1 Rapid global warming and oceanic oxygen deficiency during the Early Jurassic Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event at around 183 Ma is associated with a major turnover of marine biota linked to volcanic activity. The impact of the event on land-based eco- systems and the processes that led to oceanic anoxia remain poorly understood. Here we present analyses of spore–pollen assemblages from Pliensbachian–Toarcian rock samples that record marked changes on land during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event. Vegetation shifted from a high-diversity mixture of conifers, seed ferns, wet-adapted ferns and lycophytes to a low-diversity assemblage dominated by cheirolepid conifers, cycads and Cerebropollenites-producers, which were able to sur- vive in warm, drought-like conditions. Despite the rapid recovery of floras after Toarcian global warming, the overall community composition remained notably different after the event. In shelf seas, eutrophication continued throughout the Toarcian event. This is reflected in the overwhelming dominance of algae, which contributed to reduced oxygen conditions and to a marked decline in dinoflagellates. The substantial initial vegetation response across the Pliensbachian/Toarcian boundary compared with the relatively minor marine response highlights that the impacts of the early stages of volcanogenic -

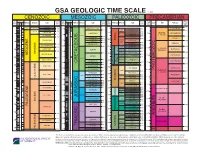

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Thallium Isotopes Reveal Protracted Anoxia During the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) Associated with Volcanism, Carbon Burial, and Mass Extinction

Thallium isotopes reveal protracted anoxia during the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) associated with volcanism, carbon burial, and mass extinction Theodore R. Them IIa,b,c,1, Benjamin C. Gillc, Andrew H. Caruthersd, Angela M. Gerhardtc,e, Darren R. Gröckef, Timothy W. Lyonsg, Selva M. Marroquínc, Sune G. Nielsenh, João P. Trabucho Alexandrei, and Jeremy D. Owensa,b aDepartment of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306; bNational High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310; cDepartment of Geosciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061; dDepartment of Geosciences, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI 49006; eEnervest Operating Company, Houston, TX 77002; fDepartment of Earth Sciences, Durham University, DH1 3LE Durham, United Kingdom; gDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521; hDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543; and iDepartment of Earth Sciences, Universiteit Utrecht, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands Edited by Donald E. Canfield, Institute of Biology and Nordic Center for Earth Evolution, University of Southern Denmark, Odense M., Denmark, and approved May 16, 2018 (received for review February 28, 2018) For this study, we generated thallium (Tl) isotope records from of these black shales with positive excursions in the marine carbon two anoxic basins to track the earliest changes in global bottom isotope record was subsequently documented (10). These excursions 13 water oxygen contents over the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T- have been interpreted to reflect the elevated burial of C-depleted OAE; ∼183 Ma) of the Early Jurassic. The T-OAE, like other Meso- organic carbon during the OAE (e.g., refs. -

2009 Geologic Time Scale Cenozoic Mesozoic Paleozoic Precambrian Magnetic Magnetic Bdy

2009 GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST. HIST. ANOM. ANOM. (Ma) CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 65.5 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 542 CALABRIAN MAASTRICHTIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE 1.8 31 C31 251 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 70.6 254 2A PIACENZIAN 32 C32 L 630 C2A 3.6 WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN 33 CAMPANIAN CAPITANIAN 5 C3 5.3 266 750 NEOPRO- CRYOGENIAN 80 C33 M WORDIAN MESSINIAN LATE 268 TEROZOIC 3A C3A 83.5 ROADIAN 7.2 SANTONIAN 271 85.8 KUNGURIAN 850 4 276 C4 CONIACIAN 280 4A 89.3 ARTINSKIAN TONIAN C4A L TORTONIAN 90 284 TURONIAN PERMIAN 10 5 93.5 E 1000 1000 C5 SAKMARIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 297 99.6 ASSELIAN STENIAN SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 299.0 5A 100 300 GZELIAN C5A 13.8 M KASIMOVIAN 304 1200 PENNSYL- 306 1250 15 5B LANGHIAN ALBIAN MOSCOVIAN MESOPRO- C5B VANIAN 312 ECTASIAN 5C 16.0 110 BASHKIRIAN TEROZOIC C5C 112 5D C5D MIOCENE 320 318 1400 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 326 6 C6 APTIAN 20 120 1500 CALYMMIAN E 20.4 6A C6A EARLY MISSIS- M0r 125 VISEAN 1600 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 SIPPIAN M3 BARREMIAN C6C 23.0 345 6C CRETACEOUS 130 M5 130 STATHERIAN CARBONIFEROUS TOURNAISIAN 7 C7 HAUTERIVIAN 1750 25 7A M10 C7A 136 359 8 C8 L CHATTIAN M12 VALANGINIAN 360 L 1800 140 M14 140 9 C9 M16 FAMENNIAN BERRIASIAN M18 PROTEROZOIC OROSIRIAN 10 C10 28.4 145.5 M20 2000 30 11 C11 TITHONIAN 374 PALEOPRO- 150 M22 2050 12 E RUPELIAN -

Ocean Acidification During the Early Toarcian

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47781.1 Manuscript received 20 April 2020 Revised manuscript received 29 June 2020 Manuscript accepted 6 July 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 13 August 2020 Ocean acidification during the early Toarcian extinction event: Evidence from boron isotopes in brachiopods Tamás Müller1*, Hana Jurikova2,3, Marcus Gutjahr2, Adam Tomašových1, Jan Schlögl4, Volker Liebetrau2, Luís v. Duarte5, Rastislav Milovský1, Guillaume Suan6, Emanuela Mattioli6,7, Bernard Pittet6 and Anton Eisenhauer2 1 Earth Science Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dˇ umbierska 1, 974 01 Banská Bystrica, Slovakia 2 GEOMAR Helmholtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel, Wischhofstr. 1-3, 24148 Kiel, Germany 3 GFZ Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum–Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 4 Department of Geology and Paleontology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynská dolina, Ilkovicˇova 6, SK-842 15 Bratislava, Slovakia 5 University of Coimbra, MARE–Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre–Department of Earth Sciences, Polo II, Rua Sílvio Lima, 3030-790 Coimbra, Portugal 6 Univ Lyon, Univ Lyon 1, ENSL, CNRS, LGL-TPE, F-69622, Villeurbanne, France 7 Institut Universitaire de France (IUF), 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France ABSTRACT methane, have also been postulated (Hesselbo The loss of carbonate production during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE, ca. et al., 2000; Them et al., 2017). 183 Ma) is hypothesized to have been at least partly triggered by ocean acidification linked The changes in the carbon cycle are globally to magmatism from the Karoo-Ferrar large igneous province (southern Africa and Antarc- expressed as a short negative shift in the car- tica). -

Paleozoic–Mesozoic Eustatic Changes and Mass Extinctions: New Insights from Event Interpretation

life Article Paleozoic–Mesozoic Eustatic Changes and Mass Extinctions: New Insights from Event Interpretation Dmitry A. Ruban K.G. Razumovsky Moscow State University of Technologies and Management (the First Cossack University), Zemlyanoy Val Street 73, 109004 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 14 November 2020 Abstract: Recent eustatic reconstructions allow for reconsidering the relationships between the fifteen Paleozoic–Mesozoic mass extinctions (mid-Cambrian, end-Ordovician, Llandovery/Wenlock, Late Devonian, Devonian/Carboniferous, mid-Carboniferous, end-Guadalupian, end-Permian, two mid-Triassic, end-Triassic, Early Jurassic, Jurassic/Cretaceous, Late Cretaceous, and end-Cretaceous extinctions) and global sea-level changes. The relationships between eustatic rises/falls and period-long eustatic trends are examined. Many eustatic events at the mass extinction intervals were not anomalous. Nonetheless, the majority of the considered mass extinctions coincided with either interruptions or changes in the ongoing eustatic trends. It cannot be excluded that such interruptions and changes could have facilitated or even triggered biodiversity losses in the marine realm. Keywords: biotic crisis; global sea level; life evolution 1. Introduction During the whole Phanerozoic, mass extinctions stressed the marine biota many times. They triggered disappearances of numerous species, genera, families, and even high-order groups of marine organisms, and they were often associated with outstanding environmental catastrophes such as global events of anoxia and euxinia, unusual warming and planetary-scale glaciations, massive volcanism, and extraterrestrial impacts. Mass extinctions were highly complex events, with the intensity amplified by the interplay among atmosphere, oceans, geologic activity, and extraterrestrial influences. The relevant knowledge is huge, and it continues to grow. -

Ocean Circulation in the Toarcian (Early Jurassic)

Ocean Circulation in the Toarcian (Early Jurassic): A Key Control on Deoxygenation and Carbon Burial on the European Shelf Itzel Ruvalcaba Baroni, Alexandre Pohl, Niels van Helmond, Nina Papadomanolaki, Angela Coe, Anthony Cohen, Bas van de Schootbrugge, Yannick Donnadieu, Caroline Slomp To cite this version: Itzel Ruvalcaba Baroni, Alexandre Pohl, Niels van Helmond, Nina Papadomanolaki, Angela Coe, et al.. Ocean Circulation in the Toarcian (Early Jurassic): A Key Control on Deoxygenation and Carbon Burial on the European Shelf. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, American Geophysical Union, 2018, 33 (9), pp.994-1012. 10.1029/2018PA003394. hal-02902799 HAL Id: hal-02902799 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02902799 Submitted on 17 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology RESEARCH ARTICLE Ocean Circulation in the Toarcian (Early Jurassic): A Key Control 10.1029/2018PA003394 on Deoxygenation and Carbon Burial on the European Shelf Key Points: • The southern European Shelf Itzel Ruvalcaba Baroni1 , Alexandre Pohl2 , Niels A. G. M. van Helmond1 , Nina M. remained oxygenated during the Papadomanolaki1 , Angela L. Coe3 , Anthony S. Cohen3, Bas van de Schootbrugge1 , Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 1 • Ocean dynamics, notably the Tethyan Yannick Donnadieu , and Caroline P. -

Diversity Dynamics of Early–Middle Jurassic Brachiopods of Caucasus, and the Pliensbachian–Toarcian Mass Extinction

Diversity dynamics of Early–Middle Jurassic brachiopods of Caucasus, and the Pliensbachian–Toarcian mass extinction DMITRY A. RUBAN Ruban, D.A. 2004. Diversity dynamics of Early–Middle Jurassic brachiopods of Caucasus, and the Pliensbachian– Toarcian mass extinction. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (2): 275–282. Taxonomic diversity of NW Caucasus brachiopods changed cyclically in the Early–Middle Jurassic. Diversifications took place in the Late Sinemurian–Early Pliensbachian, Middle–Late Toarcian and Late Aalenian–Early Bajocian, while diversity decreases occured in Late Pliensbachian–Early Toarcian, Early Aalenian and Late Bajocian. Outstanding diver− sity decline in the Late Pliensbachian–Early Toarcian corresponds to a global mass extinction interval, whose peak has been documented in the Early Toarcian. Similar diversity changes of brachiopods are observed in other Tethyan regions, including the well−studied Bakony Mountains, although in NW Caucasus the recovery after demise have begun earlier. The causes of Pl−To mass extinction in the studied region are enigmatic. Probably, it could be linked to anoxia, but its cor− respondence to the beginning of transgression is not coincident with the global record, so eustatic causes seem to be doubtful for this region. Key words: Brachiopoda, taxonomic diversity, mass extinction, Jurassic, Caucasus, Russia. Dmitry A. Ruban [ruban−[email protected]], Geology−Geography Faculty, Rostov State University, Zorge st., 40, Rostov−na− Donu, 344090, Russia; correspondence address: Tchistopolskaja st., 3, App. 10, Rostov−na−Donu, 344032, Russia. Introduction Every mass extinction should be studied both using com− parative global and regional data analyses to understand The Late Pliensbachian–Early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) mass better its appearance in geological time and space. -

Strategies for Assessing Early–Middle (Pliensbachian–Aalenian) Jurassic Cyclochronologies

Strategies for assessing Early–Middle (Pliensbachian–Aalenian) Jurassic cyclochronologies By Linda A. Hinnov1 and Jeffrey J. Park2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 2Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA There are a number of fundamental problems in assessing the astronomically forced cyclostratigraphy of the Jurassic Period. First, Jurassic geochronology is not well constrained, due to a general scarcity of radiometric dates, inferior precision of the existing ones, and large inaccuracies in stratigraphic constraints. These problems are particularly troublesome in the Early to Middle Jurassic cyclic carbonates of the Colle di Sogno section in the Lombardy Pre-Alps, Italy. Second, Jurassic sedi- mentary formations have undergone significant diagenesis, and again, the Colle di Sogno carbonates, with their location on the southern edge of the Alpine fold belt, are no exception. This prevents the recovery of the primary geochemical proxies needed to evaluate the relationship between cyclic sedimentation and orbital forcing. Finally, even when a strong case can be made for orbitally forced cycles, a direct calibration between the Jurassic and existing theoretical orbital solutions is not yet possible. However, at Colle di Sogno new nannofossil biostratigraphy provides the opportunity to make significant headway in recognizing Jurassic signals consistent with orbital theory, and to propose cyclochronological estimates for a portion of the Pliensbachian, and for the combined Toarcian–Aalenian Stages. We evaluate the presence of orbital signals in the sequence through the use of frequency modulation analysis of the cycles, as well as by spectral analysis of lithologic rank time-series reconstructions. -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2018/07 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age GSSP GSSP GSSP GSSP EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon Erathem / Era System / Period GSSA age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 541.0 ±1.0 U/L Meghalayan 0.0042 Holocene M Northgrippian 0.0082 Tithonian Ediacaran L/E Greenlandian 152.1 ±0.9 ~ 635 Upper 0.0117 Famennian Neo- 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian Callovian 1000 Quaternary Gelasian 166.1 ±1.2 2.58 Bathonian 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Middle 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Bajocian 170.3 ±1.4 Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Devonian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Proterozoic Neogene Sinemurian Langhian 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- 2050 Burdigalian Hettangian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 27.82 Gorstian -

Leroy 2021 P3 Later Cambrian

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 566 (2021) 110209 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Variable redox conditions as an evolutionary driver? A multi-basin comparison of redox in the middle and later Cambrian oceans (Drumian-Paibian) Matthew A. LeRoy a, Benjamin C. Gill a,*, Erik A. Sperling b, N. Ryan McKenzie c, Tae-Yoon S. Park d a Department of Geosciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA b Department of Geological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA c Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulham, Hong Kong, China d Division of Polar Earth-System Sciences, Korea Polar Research Institute, 26 Songdomirae-ro Yeonsu-gu, Incheon 21990, Republic of Korea ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The middle to later Cambrian (Drumian-Jiangshanian Ages, 505–490 Ma) was a time of unique evolutionary Cambrian dynamics that remain enigmatic. This interval records unusually high rates of faunal turnover that produced a Marine redox “plateau” within the broader trajectory of rapidly increasing biodiversity seen across the Cambrian Explosion and Sedimentary redox Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE). The oceans during this time are generally thought to have Iron speciation been less oxygenated than later in the Phanerozoic, yet knowledge of oceanic redox structure and the influence DICE SPICE this exerted upon the biosphere remains limited. Importantly, this interval also encompasses two large carbon cycle perturbations—the DICE and SPICE events— that are thought to involve the expansion of anoxic and, more specifically euxinic regions in the ocean. Despite this supposition, direct characterization of redox conditions across this time remains limited. -

Warming-Driven Mass Extinction in the Early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) of Northern and Central Spain

Warming-driven mass extinction in the Early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) of northern and central Spain. Correlation with other time-equivalent European sections a, b Juan J. Gómez ⁎, Antonio Goy a Dpto. de Estratigrafía, Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas (UCM) and Instituto de Geociencias (CSIC-UCM), 28040 Madrid, Spain b Dpto. de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas (UCM) and Instituto de Geociencias (CSIC-UCM), 28040 Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT Causes of the major mass extinction recorded during the Early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) are controversial. Many authors have concluded that the mass extinction is caused by the widespread oceanic anoxia derived from a postulated Early Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (ETOAE), supposedly synchronous in all basins and global in extent. Another group of papers links the mass extinction with a major climate change that occurred synchronously with the mass extinction. The results of the study of five sections of the uppermost Pliensbachian and Lower–Middle Toarcian deposits, located in northern and central Spain are presented. Detailed ammonite-based biostratigraphy, coupled with stable isotope analysis of belemnite calcite and bulk carbonates, as well as total organic carbon (TOC) analyses have been performed in all sections. Records of the vertical distribution of mainly benthic fossils have been compiled in four of the studied sections. Results obtained in the Spanish outcrops have been compared and correlated with other European sections. The excellent mutual relation between the patterns of the Early Toarcian progressive warming and the concomitant progressive losses of species evidences a cause-and-effect relationship between the increase of temperature and the mass extinction. From an uppermost Pliensbachian cooling interval, warming started at the Lower Toarcian Tenuicostatum Zone.