Wagner the Ring an Orchestral Adventure Arranged by Henk De Vlieger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katarina Dalayman Soprano

KATARINA DALAYMAN SOPRANO BIOGRAPHY LONG VERSION Swedish soprano Katarina Dalayman has sustained a long and prestigious international career in the dramatic repertoire and she has enjoyed enduring collaborations with many of today’s foremost conductors. Strong, dramatic interpretations married with impeccable musicianship are her characteristics. Dalayman has performed a wide range of roles including Isolde (Tristan und Isolde), Marie (Wozzeck), Lisa (Queen of Spades), Ariadne (Ariadne auf Naxos), Katarina Ismailova (Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk) and the title role of Elektra. With a particularly strong association to Wagner's Brünnhilde, Dalayman has appeared in Ring cycles at The Metropolitan Opera, Opéra National de Paris, Wiener and Bayerische staatsoper, Teatro alla Scala, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Semperoper Dresden, Salzburger Festspiele and Festival d’Aix en Provence. Looking ahead to the next phase in her career, Katarina Dalayman’s repertoire is now focused on new roles, having recently made her debut as Kundry (Parsifal) in Dresden, Paris and Stockholm, Judith (Duke Bluebeard’s Castle) in Barcelona and London (Royal Opera House), Ortrud (Lohengrin) with Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and Brangäne (Tristan und Isolde) at The Metropolitan Opera. She has recently appeared as Herodias (Salome) for Royal Swedish Opera, Foreign Princess (Rusalka) at The Metropolitan Opera, Klytämnestra (Elektra), Amneris (Aida), and Kostelnicka (Jenůfa), all for Royal Swedish Opera. Among recent performances can be mentioned her highly celebrated interpretation of Kundry at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, a production that was broadcasted around the world in the Mets “Live in HD” performance transmissions, an appearance together with Bryn Terfel in Die Walküre at the Tanglewood Festival in USA, an interpretation of Carmen and Elisabetta in Maria Stuarda both at the Royal Swedish Opera and Ortrud in Lohengrin, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. -

My Fifty Years with Wagner

MY FIFTY YEARS WITH RICHARD WAGNER I don't for a moment profess to be an expert on the subject of the German composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner and have not made detailed comments on performances, leaving opinions to those far more enlightened than I. However having listened to Wagnerian works on radio and record from the late 1960s, and after a chance experience in 1973, I have been fascinated by the world and works of Wagner ever since. I have been fortunate to enjoy three separate cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen, in Bayreuth 2008, San Francisco in 2011 and Melbourne in 2013 and will see a fourth, being the world's first fully digitally staged Ring cycle in Brisbane in 2020 under the auspices of Opera Australia. I also completed three years of the degree course in Architecture at the University of Quensland from 1962 and have always been interested in the monumental buildings of Europe, old and new, including the opera houses I have visited for performance of Wagner's works. It all started in earnest on September 29, 1973 when I was 28 yrs old, when, with friend and music mentor Harold King of ABC radio fame, together we attended the inaugural orchestral concert given at the Sydney Opera House, in which the legendary Swedish soprano Birgit Nilsson opened the world renowned building singing an all Wagner programme including the Immolation scene from Götterdämmerung, accompanied by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by a young Charles Mackerras. This event fully opened my eyes to the Ring Cycle - and I have managed to keep the historic souvenir programme. -

Opera Bands and Artists List

Opera Bands and Artists List Szeged Symphony https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/szeged-symphony-orchestra-265888/albums Orchestra Marek Torzewski https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/marek-torzewski-11768532/albums Frederic Toulmouche https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/frederic-toulmouche-20001877/albums Dominique Girod https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/dominique-girod-16056863/albums Livia Budaï-Batky https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/livia-buda%C3%AF-batky-26988123/albums Vitaliy Kil'chevskiy https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/vitaliy-kil%27chevskiy-19850392/albums Yaniv D'Or https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/yaniv-d%27or-16131484/albums Malvīne Vīgnere- https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/malv%C4%ABne-v%C4%ABgnere-gr%C4%ABnberga- Grīnberga 16363082/albums Rosa Rimoch https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/rosa-rimoch-29419597/albums Karine Babajanyan https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/karine-babajanyan-18628035/albums Jean-Baptiste Mathieu https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/jean-baptiste-mathieu-11927434/albums Opera Las Vegas https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/opera-las-vegas-16960608/albums Vicente Forte https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/vicente-forte-11954634/albums Albert Lim https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/albert-lim-23887792/albums Alban Berg https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/alban-berg-78475/albums Bedřich Diviš Weber https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/bed%C5%99ich-divi%C5%A1-weber-79023/albums -

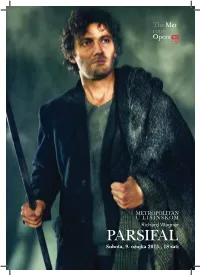

PARSIFAL Subota, 9

Richard Wagner PARSIFAL Subota, 9. ožujka 2013., 18 sati Foto: Metropolitan opera Richard Wagner PARSIFAL Subota, 9. ožujka 2013., 18 sati SNIMKA THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Richard Wagner PARSIFAL Ein Bühnenweihfestspiel / Sveani posvetni prikaz u tri ina Libreto: Richard Wagner prema Wolframu von Eschenbachu SUBOTA, 9. OŽUJKA 2013. POČETAK U 18 SATI. Praizvedba: Bayreuth, 26. srpnja 1882. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno kazalište u Zagrebu, 28. travnja 1922. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 24. prosinca 1903. Prva izvedba ove produkcije: 15. veljače 2013. PARSIFAL Jonas Kaufmann REDATELJ François Girard KUNDRY Katarina Dalayman SCENOGRAF Michael Levine GURNEMANZ René Pape KOSTIMOGRAF Thibault AMFORTAS Peter Mattei Vancraenenbroeck KLINGSOR Evgenij Nikitin OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE David Finn TITUREL Rúni Brattaberg Solisti, Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana OBLIKOVATELJ VIDEA Peter Flaherty ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo KOREOGRAFKINJA Carolyn Choa DIRIGENT Daniele Gatti DRAMATURG Serge Lamothe Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u dvorcu Montsalvat u Španjolskoj u srednjem vijeku. Parsifal nije samo opera - Parsifal je misija u kojoj je Wagner, već potkraj života, težio pomirenju svih aspekta svoje duhovnosti. To je sveto djelo u povijesti glazbe. François Girard Stanka poslije prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 23 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: njemački. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Sveti gral, posuda iz koje je Spasitelj pio na Nesvjestan ljudske slabosti, pao je pod utjecaj posljednjoj veeri, dan je na uvanje Titurelu Kundry i zaboravio svoje poslanstvo. -

Katarina Dalayman Soprano

KATARINA DALAYMAN SOPRANO BIOGRAPHY LONG VERSION Swedish soprano Katarina Dalayman has sustained a long and prestigious international career in the dramatic repertoire and she has enjoyed enduring collaborations with many of today’s foremost conductors. Strong, dramatic interpretations married with impeccable musicianship are her characteristics. Dalayman has performed a wide range of roles including Isolde (Tristan und Isolde), Marie (Wozzeck), Lisa (Queen of Spades), Ariadne (Ariadne auf Naxos), Katarina Ismailova (Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk) and the title role of Elektra. With a particularly strong association to Wagner's Brünnhilde, Dalayman has appeared in Ring cycles at The Metropolitan Opera, Opéra National de Paris, Wiener and Bayerische staatsoper, Teatro alla Scala, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Semperoper Dresden, Salzburger Festspiele and Festival d’Aix en Provence. Looking ahead to the next phase in her career, Katarina Dalayman’s repertoire is now focused on new roles, having recently made her debut as Kundry (Parsifal) in Dresden, Paris and Stockholm, Judith (Duke Bluebeard’s Castle) in Barcelona and London (Royal Opera House), Ortrud (Lohengrin) with Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and Brangäne (Tristan und Isolde) at The Metropolitan Opera. She has recently appeared as Herodias (Salome) for Royal Swedish Opera, Foreign Princess (Rusalka) at The Metropolitan Opera, and this season she makes role debuts as Klytämnestra (Elektra), Amneris (Aida), and Kostelnicka (Jenůfa), all for Royal Swedish Opera. Among recent performances can be mentioned her highly celebrated interpretation of Kundry at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, a production that was broadcasted around the world in the Mets “Live in HD” performance transmissions, an appearance together with Bryn Terfel in Die Walküre at the Tanglewood Festival in USA, an interpretation of Carmen and Elisabetta in Maria Stuarda both at the Royal Swedish Opera and Ortrud in Lohengrin, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. -

Annual Report 2017–18

Annual Report 2017–18 1 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 2 Introduction During the 2017–18 season, the Metropolitan Opera presented more than 200 exiting performances of some of the world’s greatest musical masterpieces, with financial results resulting in a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses—the fourth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Bellini’s Norma and also included four other new productions, as well as 19 revivals and a special series of concert presentations of Verdi’s Requiem. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 12th year, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office and media) totaled $114.9 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All five new productions in the 2017–18 season were the work of distinguished directors, three having had previous successes at the Met and one making an auspicious company debut. A veteran director with six prior Met productions to his credit, Sir David McVicar unveiled the season-opening new staging of Norma as well as a new production of Puccini’s Tosca, which premiered on New Year’s Eve. The second new staging of the season was also a North American premiere, with Tom Cairns making his Met debut directing Thomas Adès’s groundbreaking 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel. -

For the First Time, AIDA at the Royal Swedish Opera Broadcasted Worldwide

Stockholm 2018-03-16 For the first time, AIDA at the Royal Swedish Opera Broadcasted Worldwide On the 17th of March at 3 pm (CET), Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida from the Royal Swedish Opera will be broadcasted live in Europe via OperaVision, a new open platform for live streaming. Following the premiere on the 24th of February, the performance with a young and aspiring cast was completely sold out. The title role, Aida, is portrayed by the 27-year-old Swedish soprano Christina Nilsson who has made a sensational debut at the Royal Swedish Opera. Media has particularly praised the credibility of the young love couple. Aida’s beloved Radamès is portrayed by the 30- year-old Italian tenor Ivan Defabiani. Canadian Director Michael Cavanagh has staged a love triangle where Aida, a prisoner of war; commander Radamès and princess Amneris are torn between unyielding private emotions and public obligations. The internationally celebrated Royal Court Singer Katarina Dalayman has received great reviews for her part as Amneris. ”Aida never ceases to fascinate us. It is an impossible love story really, and through the music we are thrown between hope and despair,” says Birgitta Svendén, CEO and Artistic Director of the Royal Swedish Opera. The EU funded open platform OperaVision, was launched in 2017 by 30 opera companies from 18 countries. The platform is part of Opera Europa, a European association for opera companies and festivals. The Royal Swedish Opera has been part of the association since it started up in 2003 with Birgitta Svendén, as the Board Chairperson. KUNGLIGA OPERAN AB Box 160 94, 103 22 Stockholm BESÖKSADRESS Jakobs Torg 4 WWW . -

Wagner Quarterly 133, June 2014

WAGNER SOCIETY nsw ISSUE NO 6 CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF RICHARD WAGNER WAGNER QUARTERLY 133 JUNE 2014 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Welcome to the second Quarterly for 2014. 2014 is, for obvious reasons, a quieter year than was last year. Nevertheless, we have some very special events planned for the year. We have already started on a high note. After our first event, involving cast members from the Melbourne Ring, we had meetings in March and April consisting of fascinating expositions from the two Dr Davids: Dr David Schwartz talking about family dysfunction in the Wagner clan, and Dr David Larkin talking about the two Richards: Wagner and Strauss. These talks are described in detail later in this quarterly, so I will not go into them here, except to say that the personal feedback from members who attended the functions was, on both occasions, full of unmitigated enthusiasm. On 25 May, we had the Society’s Annual General Meeting, which was attended by a number of members. The President’s report was, I am afraid, considerably shorter than usual, as I had returned from overseas only the day before. But I gave a brief description of our activities in 2013, many of which were, not surprisingly, geared towards the Melbourne Ring at the end of the year. The Society’s financial statements for 2013 were approved. They show the Society to be in a very solid financial position. No controversial issues were raised at the meeting, and all the items on the agenda were passed without dissent. As to the committee for the coming year, we have one new committee member: Barbara de Rome, in the place of Paulo Montoya. -

The Göteborg Opera Announces 2017-18 Season

The Göteborg Opera announces 2017-18 Season: the Scandinavian premiere of Jonathan Dove’s Monster in the Maze, a Centenary Gala to Birgit Nilsson with Nina Stemme, and a sustainable Das Rheingold in the autumn of 2018 The Göteborg Opera announces its 2017-18 Season with the Scandinavian premiere of Jonathan Dove’s opera The Monster in the Maze and two further new productions including Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos and an unusual double bill of Weill & Brecht’s Seven Deadly Sins with Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. On the centenary of legendary Swedish soprano’s birth, the Göteborg Opera will host the starriest gala to pay homage to soprano Birgit Nilsson - “a voice of heroic proportions” (Guardian) and the greatest Wagnerian soprano of her day - by lining up eight leading Swedish Wagnerian sopranos including Nina Stemme. The Göteborg Opera is currently preparing for its first Wagner Ring Cycle directed by artistic director Stephen Langridge and conducted by Evan Rogister. The Ring will commence with Das Rheingold in the autumn of 2018 continuing for 4 years culminating in the 400th anniversary of the City of Gothenburg. The autumn of 2018 will also see GöteborgsOperans Danskompani make its debut at Sadler’s Wells with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s double bill of Icon and Noetic. OPERA 21 October - 5 December 2017 NEW PRODUCTION Double bill - Seven Deadly Sins & Gianni Schicchi Double-bill directed by David Radok, conducted by Antony Hermus The season opens on 21 October with a novel pairing of Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht’s Seven Deadly Sins with Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi directed by house director David Radok. -

SEASON 2019 ‘Give Me a Laundry List and I’Ll Set It to Music’

SEASON 2019 ‘Give me a laundry list and I’ll set it to music’ – Gioachino Rossini ‘Music begins where the possibilities of language end’ – Richard Wagner ‘When I’m writing a song, I try to be the character’ –Stephen Sondheim WELCOME SEASON 2019 Open up to new horizons Welcome to Victorian Opera’s Victorian Opera continues its Season 2019. The notion of horizons celebration of bel canto and its rich animates this year; a word with many tradition with an evening of Heroic connotations, we explore the idea of Bel Canto, highlighting singing at its goals to be reached, the richness of most virtuosic. possibility, the potential for what lies beyond, and a voyage to such new Quirky adventures into the horizons. This program offers many unknown, and the fruitfulness of chances for your own discovery. self-discovery provide new horizons for our younger audiences with Our season opens with the luminous Alice Through the Opera Glass and beauty of Parsifal, a journey towards a new Australian opera based on the horizon of transcendental Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant. spirituality; a journey made by those on and off the stage, in the pit, and Away from the main stage, we the audience. deliver a diverse range of musical stylings and smaller recitals to From Wagner to Sondheim, we colour and enrich 2019. return to the works of the greatest living composer of music theatre Victorian Opera exists to offer you with A Little Night Music. As the sun unique and remarkable experiences, sets across the horizon, a summer as we reimagine the potential of night’s revelations await; one full of opera, for everyone. -

Rusalka Dossier .Pdf

Rusalka| Temporada 2020-2021 1 Rusalka| Temporada 2020-2021 Páginas 4 – 5 Ficha artística Páginas 6 – 7 Argumento Páginas 8 – 11 El teatro, metáfora del lago, por Joan Matabosch Páginas 12 – 18 Biografías 2 Rusalka| Temporada 2020-2021 3 Rusalka| Temporada 2020-2021 RUSALKA Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Ópera en tres actos Libreto de Jaroslav Kvapil, basado en el cuento de hadas Undine (1811) de Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué e inspirado en el cuento La sirenita (1837) de Hans Christian Andersen y otros relatos europeos Estrenada en el Teatro Nacional de Praga el 31 de marzo de 1901 Estrenada en el Teatro Real el 15 de marzo de 1924 Nueva producción del Teatro Real, en coproducción con la Semperoper de Dresde, el Teatro Comunale de Bolonia, el Gran Teatre del Liceu de Barcelona y el Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía de Valencia EQUIPO ARTÍSTICO Director musical Ivor Bolton Director de escena Christof Loy Escenógrafo Johannes Leiacker Figurinista Ursula Rezenbrink Iluminador Bernd Purkrabek Coreógrafo Klevis Elmazaj Director del coro Andrés Máspero Asistente del director musical Tim Anderson Asistentes del director de escena Frederick Buhr, Johannes Stepanek, Axel Weidauer Asistente de la figurinista Gabriela Hidalgo Supervisora de dicción checa Lada Valesova REPARTO Rusalka Asmik Grigorian (12, 14, 16, 22, 25, 27) Olesya Golovneva (13, 15, 24, 26) El príncipe Eric Cutler (12, 14, 16, 22, 25, 27) David Butt Philip (13, 15, 24, 26) La princesa extranjera Karita Mattila (12, 14, 16, 22, 25, 27) Rebecca von Lipinski (13, 15, 24, 26) 4 Rusalka| Temporada -

Wagner's Ring Cycle Stockholm

WAGNER'S RING CYCLE STOCKHOLM Stockholm - 09 days Departure: May 22, 2017 Return: May 30, 2017 Do not miss a unique opportunity to experience Richard Wagner’s unassailable tetralogy of the Ring Cycle, sung by the world-renowned Nina Stemme, born in Stockholm, as Brünnhilde. This critically acclaimed production premiered at the Royal Swedish Opera 10 years ago and has been praised for its brilliant character portraits and the orchestra’s breath taking performance. Director Staffan Valdemar Holm has put particular focus on the strong relationship between the father Wotan and the daughter Brünnhilde – love versus power, love as a catastrophe – that is what the operas are about. We have chosen to stay at the finest deluxe hotel in Scandinavia, the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. Opera Performances In Stockholm: MAY 24 - Das Rheingold MAY 25 - Die Walküre MAY 27 - Siesiegfried MAY 29 - Götterdämmerung DIRECTOR - Staffan Valdemar Holm STAGING BY - Bente Lykke Møller CAST Wotan - John Lundgren Siegmund - Michael Weinius Siegfried - Daniel Frank Alberich - Johan Edholm Brünnhilde - Nina Stemme Mime - Niklas Bjorling Rygert Frica - Katarina Dalayman Erda - Katarine Leosson Monday, May 22. (D) *. DEPART FOR STOCKHOLM Depart today on any airline of your choice from home to Stockholm, Sweden, arriving the next day. Dinner and light breakfast served onboard the plane. Tuesday, May 23. (B,D). STOCKHOLM Upon arrival at the Stockholm International Airport, take a taxi to the super deluxe centrally located GRAND HOTEL, where we stay seven nights. We will reimburse you the taxi fare. Briefing, cocktails and Gala Welcome dinner at the hotel’s gourmet restaurant. Wednesday, May 24.