13895 Wagner News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

Applause Magazine, Applause Building, 68 Long Acre, London WC2E 9JQ

1 GENE WIL Laughing all the way to the 23rd Making a difference LONDON'S THEATRE CRITI Are they going soft? PIUS SAVE £££ on your theatre tickets ,~~ 1~~EGm~ Gf1ll~ G~rick ~he ~ ~ e,London f F~[[ IIC~[I with ever~ full price ticket purchased ~t £23.50 Phone 0171-312 1991 9 771364 763009 Editor's Letter 'ThFl rul )U -; lmalid' was a phrase coined by the playwright and humourl:'t G eorge S. Kaufman to describe the ailing but always ~t:"o lh e m Broadway Theatre in the late 1930' s . " \\ . ;t" )ur ul\'n 'fabulous invalid' - the West End - seems in danger of 'e:' .m :: Lw er from lack of nourishmem, let' s hope that, like Broadway - presently in re . \ ,'1 'n - it too is resilient enough to make a comple te recovery and confound the r .: i " \\' ho accuse it of being an en vironmenta lly no-go area whose theatrical x ;'lrJ io n" refuse to stretch beyond tired reviva ls and boulevard bon-bons. I i, clUite true that the season just past has hardly been a vintage one. And while there is no question that the subsidised sector attracts new plays that, =5 'ears ago would a lmost certainly have found their way o nto Shaftes bury Avenue, l ere is, I am convinced, enough vitality and ingenuity left amo ng London's main -s tream producers to confirm that reports of the West End's te rminal dec line ;:m: greatly exaggerated. I have been a profeSSi onal reviewer long enough to appreciate the cyclical nature of the business. -

Katarina Dalayman Soprano

KATARINA DALAYMAN SOPRANO BIOGRAPHY LONG VERSION Swedish soprano Katarina Dalayman has sustained a long and prestigious international career in the dramatic repertoire and she has enjoyed enduring collaborations with many of today’s foremost conductors. Strong, dramatic interpretations married with impeccable musicianship are her characteristics. Dalayman has performed a wide range of roles including Isolde (Tristan und Isolde), Marie (Wozzeck), Lisa (Queen of Spades), Ariadne (Ariadne auf Naxos), Katarina Ismailova (Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk) and the title role of Elektra. With a particularly strong association to Wagner's Brünnhilde, Dalayman has appeared in Ring cycles at The Metropolitan Opera, Opéra National de Paris, Wiener and Bayerische staatsoper, Teatro alla Scala, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Semperoper Dresden, Salzburger Festspiele and Festival d’Aix en Provence. Looking ahead to the next phase in her career, Katarina Dalayman’s repertoire is now focused on new roles, having recently made her debut as Kundry (Parsifal) in Dresden, Paris and Stockholm, Judith (Duke Bluebeard’s Castle) in Barcelona and London (Royal Opera House), Ortrud (Lohengrin) with Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and Brangäne (Tristan und Isolde) at The Metropolitan Opera. She has recently appeared as Herodias (Salome) for Royal Swedish Opera, Foreign Princess (Rusalka) at The Metropolitan Opera, Klytämnestra (Elektra), Amneris (Aida), and Kostelnicka (Jenůfa), all for Royal Swedish Opera. Among recent performances can be mentioned her highly celebrated interpretation of Kundry at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, a production that was broadcasted around the world in the Mets “Live in HD” performance transmissions, an appearance together with Bryn Terfel in Die Walküre at the Tanglewood Festival in USA, an interpretation of Carmen and Elisabetta in Maria Stuarda both at the Royal Swedish Opera and Ortrud in Lohengrin, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

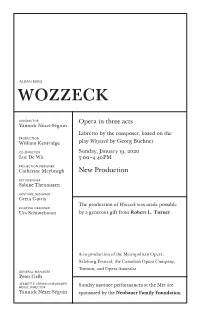

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008).