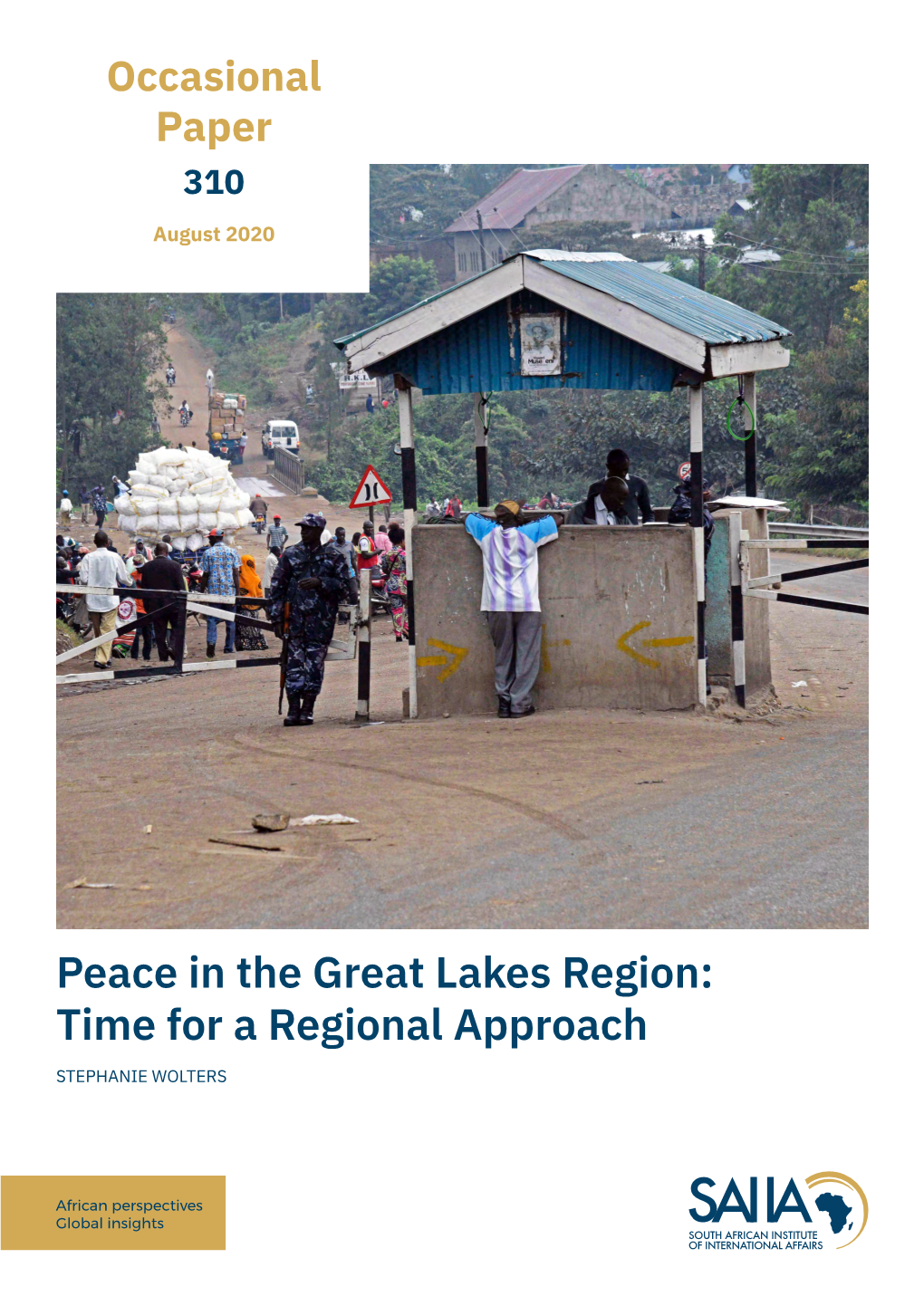

Peace in the Great Lakes Region: Time for a Regional Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nyamwasa-Q-And-A.Pdf

CASE OVERVIEW Consortium for Refugees and Migrants Rights in South Africa v President of the Republic of South Africa and Others On 29 and 30 October 2012 CoRMSA will argue before the North Gauteng High Court, Pretoria that former Rwandan general and suspected war criminal, Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, is not eligible for refugee status. This case is supported by the Southern Africa Litigation Centre and CoRMSA is represented by the Wits Law Clinic. 1. What is this case about? This case concerns the judicial review of the decision of the South African authorities to grant refugee status to a former Rwandan general and suspected war criminal, Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, in June 2010. This case is being brought by the Consortium for Refugees and Migrants Rights in South Africa (CoRMSA) and is supported by the Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC). It raises a number of issues, including: ▪ The proper interpretation and administration of South Africa’s Refugees Act in accordance with international law; ▪ The intersection between refugee law and international criminal law and the detection and apprehension of persons accused of international crimes; ▪ South Africa’s obligation to ensure that it does not become a safe haven for perpetrators of international crimes; ▪ South Africa’s constitutional mandate to ensure accountable, transparent and rational decision making. This case will be heard on 29 and 30 October by Judge Mngqibisa-Thusi of the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria. 2. Who is Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa? Nyamwasa is a Rwandan national and former general in the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA). Nyamwasa was a high-ranking member of the RPA between 1990 and 1998, during which time he was in command of troops stationed on the border between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda. -

Proceedings of the First Joint Annual Meetings

Economic Commission for Africa African Union Commission Proceedings of the First Joint Annual Meetings African Union Conference of Ministers of Economy and Finance and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development 2008 AFRICAN UNION UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA Forty-first session of the Economic Commission for Africa Third session of CAMEF 31 March – 2 April 2008 • First Joint Annual Meetings of the African Union Conference of Ministers of Economy and Finance and the Economic Commission for Africa Distr.: General Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning E/ECA/CM/41/4 and Economic Development AU/CAMEF/MIN/Rpt(III) Date: 10 April 2008 • Commemoration of ECA’s 50th Anniversary Original: English Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Proceedings of the First Joint Annual Meetings of the African Union Conference of Ministers of Economy and Finance and the Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Proceedings of the First Joint Annual Meetings Contents A. Attendance 1 B. Opening of the Conference and Presidential Reflections 2 C. Election of the Bureau 7 D. High-level thematic debate 7 E. Adoption of the agenda and programme of work 11 F. Account of Proceedings 11 Annex I: A. Resolutions adopted by the Joint Conference 20 B. Ministerial Statement adopted by the Joint Conference 27 C. Solemn Declaration on the 50th Anniversary of the Economic Commission for Africa 33 Annex II: Report of the Committee of Experts of the First Joint Meeting of the AU Conference of Ministers of Economy and Finance and ECA Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development 35 E/ECA/CM/41/4 iii AU/CAMEF/MIN/Rpt(III) Proceedings of the First Joint Annual Meetings A. -

Mkapa, Benjamin William

BENJAMIN WILLIAM MKAPA DCL Mr Chancellor, There’s something familiar about Benjamin Mkapa’s story; a graduate joins a political party with socialist leanings, rises rapidly through the establishment then leads a landslide electoral victory, he focuses on education and helps shift the economy to a successful and stable mixed model. He is popular though he does suffer criticism over his military policy from Clare Short. Then after 10 years he steps down, voluntarily. Tell this story to a British audience and few would think of the name Mkapa. Indeed, if you showed his picture most British people would have no idea who he was. This anonymity and commendable political story are huge achievements for he was a leader of a poor African country that was still under colonial rule less than 50 years ago. He’s not a household name because he did not preside over failure, nor impose dictatorial rule, he did not steal his people’s money or set tribal groups in conflict. He was a good democratic leader, an example in a continent with too few. The potential for failure was substantial. His country of 120 ethnic groups shares borders with Mozambique, Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. It ranks 31st in size in the world, yet 1 when it was redefined in 1920 the national education department had three staff. The defeat of Germany in 1918 ended the conflict in its East African colony and creation of a new British protectorate, Tanganyika. In 1961 the country achieved independence and three years later joined with Zanzibar to create Tanzania. -

Forty Days and Nights of Peacemaking in Kenya

Page numbering! JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS FORTY DAYS AND NIGHTS OF PEACEMAKING IN KENYA Gilbert M Khadiagala Gilbert Khadiagala is Jan Smuts Professor of International Relations, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg e-mail: [email protected] We are ready to go the extra mile to achieve peace. Today, we take the first step. My party and I are ready for this long journey to restore peace in our land …We urge our people to be patient as parties work day and night to ensure that negotiations do not last a day longer than necessary. Raila Odinga, leader of the Orange Democratic Movement (East African Standard 25 January) Kenya is a vital country in this region and the international com- munity is not ready to watch it slump into anarchy. Norwegian Ambassador Hellen Jacobsen (East African Standard 5 February) I will stay as long as it takes to get the issue of a political settlement to an irreversible point. I will not be frustrated or provoked to leave. It is in the interest of the men and women of Kenya, the region, Africa and the international community to have a new government. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (Daily Nation 6 February) ABSTRACT Recent studies on resolving civil conflicts have focused on the role of external actors in husbanding durable agreements. The contribution of authoritative parties is vital to the mediation of conflicts where parties are frequently In the interests of avoiding repetition citations will carry the date and month only unless the year is anything other than 2008. -

Is Tanzania a Success Story? a Long Term Analysis

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS TANZANIA A SUCCESS STORY? A LONG TERM ANALYSIS Sebastian Edwards Working Paper 17764 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17764 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2012 Many people helped me with this work. In Dar es Salaam I was fortunate to discuss a number of issues pertaining to the Tanzanian economy with Professor Samuel Wangwe, Professor Haidari Amani, Dr. Kipokola, Dr. Hans Hoogeveen, Mr. Rugumyamheto, Professor Joseph Semboja, Dr. Idris Rashid, Professor Mukandala, and Dr. Brian Cooksey. I am grateful to Professor Benno Ndulu for his hospitality and many good discussions. I thank David N. Weil for his useful and very detailed comments on an earlier (and much longer) version of the paper. Gerry Helleiner was kind enough as to share with me a chapter of his memoirs. I thank Jim McIntire and Paolo Zacchia from the World Bank, and Roger Nord and Chris Papagiorgiou from the International Monetary Fund for sharing their views with me. I thank Mike Lofchie for many illuminating conversations, throughout the years, on the evolution of Tanzania’s political and economic systems. I am grateful to Steve O’Connell for discussing with me his work on Tanzania, and to Anders Aslund for helping me understand the Nordic countries’ position on development assistance in Africa. Comments by the participants at the National Bureau of Economic Research “Africa Conference,” held in Zanzibar in August 2011, were particularly helpful. I am grateful to Kathie Krumm for introducing me, many years ago, to the development challenges faced by the East African countries, and for persuading me to spend some time working in Tanzania in 1992. -

Rwanda Timeline

Rwanda Profile and Timeline 1300s - Tutsis migrate into what is now Rwanda, which was already inhabited by the Twa and Hutu peoples. [Hutus are farmers and make up > 80% of the population / Twa are the smallest group and by trade hunters and gatherers / Tutsi > 10% of the population are pastoralists] 1600s - Tutsi King Ruganzu Ndori subdues central Rwanda and outlying Hutu areas. Late 1800s - Tutsi King Kigeri Rwabugiri establishes a unified state with a centralized military structure. 1858 - British explorer Hanning Speke is the first European to visit the area. 1890 - Rwanda becomes part of German East Africa. 1916 - Belgian forces occupy Rwanda. 1923 - Belgium granted League of Nations mandate to govern Ruanda-Urundi, which it ruled indirectly through Tutsi kings. 1946 - Ruanda-Urundi becomes UN trust territory governed by Belgium. Independence 1957 - Hutus issue manifesto calling for a change in Rwanda's power structure to give them a voice commensurate with their numbers; Hutu political parties formed. 1959 - Tutsi King Kigeri V, together with tens of thousands of Tutsis, forced into exile in Uganda following inter-ethnic violence. 1961 - Rwanda proclaimed a republic. 1962 - Rwanda becomes independent with a Hutu, Gregoire Kayibanda, as president; many Tutsis leave the country. Hutu Gregoire Kayibanda was independent Rwanda's first President 1963 - Some 20,000 Tutsis killed following an incursion by Tutsi rebels based in Burundi. 1973 - President Gregoire Kayibanda ousted in military coup led by Juvenal Habyarimana. 1978 - New constitution ratified; Habyarimana elected president. 1988 - Some 50,000 Hutu refugees flee to Rwanda from Burundi following ethnic violence there. 1990 - Forces of the rebel, mainly Tutsi, Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) invade Rwanda from Uganda. -

The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS FROM CNDP TO M23 THE EVOLUTION OF AN ARMED MOVEMENT IN EASTERN CONGO rift valley institute | usalama project From CNDP to M23 The evolution of an armed movement in eastern Congo jason stearns Published in 2012 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1Df, United Kingdom. PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya. tHe usalama project The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe AUTHor Jason Stearns, author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, was formerly the Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. He is Director of the RVI Usalama Project. RVI executive Director: John Ryle RVI programme Director: Christopher Kidner RVI usalama project Director: Jason Stearns RVI usalama Deputy project Director: Willy Mikenye RVI great lakes project officer: Michel Thill RVI report eDitor: Fergus Nicoll report Design: Lindsay Nash maps: Jillian Luff printing: Intype Libra Ltd., 3 /4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London sW19 4He isBn 978-1-907431-05-0 cover: M23 soldiers on patrol near Mabenga, North Kivu (2012). Photograph by Phil Moore. rigHts: Copyright © The Rift Valley Institute 2012 Cover image © Phil Moore 2012 Text and maps published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/nc-nd/3.0. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Accountability and Clientelism in Dominant Party Politics: The Case of a Constituency Development Fund in Tanzania Machiko Tsubura Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies University of Sussex January 2014 - ii - I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………………………… - iii - UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX MACHIKO TSUBURA DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ACCOUNTABILITY AND CLIENTELISM IN DOMINANT PARTY POLITICS: THE CASE OF A CONSTITUENCY DEVELOPMENT FUND IN TANZANIA SUMMARY This thesis examines the shifting nature of accountability and clientelism in dominant party politics in Tanzania through the analysis of the introduction of a Constituency Development Fund (CDF) in 2009. A CDF is a distinctive mechanism that channels a specific portion of the government budget to the constituencies of Members of Parliament (MPs) to finance local small-scale development projects which are primarily selected by MPs. -

President Benjamin Mkapa Interviewer

An initiative of the National Academy of Public Administration, and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the Bobst Center for Peace and Justice, Princeton University Oral History Program Series: Civil Service Interview no.: Z6 Interviewee: President Benjamin Mkapa Interviewer: Jennifer Widner Date of Interview: 25 August 2009 Location: Dar es Salaam Tanzania Innovations for Successful Societies, Bobst Center for Peace and Justice Princeton University, 83 Prospect Avenue, Princeton, New Jersey, 08544, USA www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Use of this transcript is governed by ISS Terms of Use, available at www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Innovations for Successful Societies Series: Civil Service Oral History Program Interview number: Z6_CS ______________________________________________________________________ WIDNER: Thank you very much for speaking with us Your Excellency. You have been engaged in public service reform as President and subsequently you became Chair of the South Centre and may have views on the challenges facing reform leaders in other parts of the world. We wanted to speak with you about both of these subjects if possible beginning with public service management or public management reform which has gone fairly far in Tanzania even though there are still some challenges ahead. I wanted to ask you to remember back to the mid 1990s when you became President and to ask you why you decided to move forward with public management reform at that time. Some people have observed that this is a part of government activity that many people don’t like to address when they’re in office because the benefits often lie very far out in the future and there’s not much immediate political incentive yet you decided to go forward. -

H.E Benjamin William Mkapa 1938-2020 P 3 Farewellthe MONDAY, AUGUST 3, 2020

OBITUARY H.E Benjamin William Mkapa 1938-2020 P 3 FarewellThe MONDAY, AUGUST 3, 2020. NO. 03 VOL UME 02 Cavendish Success begins at Cavendish University Cavendish ready for e-learning as NCHE Inspects facilities Preparing for e-learning. The Inspection is aimed at ascertaining whether CUU is prepared and ready to offer Online teaching and learning services. CUU is privileged to be the first University in the Country to undergo this rigorous inspection. P.2 Firms relax security to fight COVID-19 Many security personnel manning many public premises are of late armed with only sanitizers and they no longer mind about check- ing people’s bags or cars for any explosives. P. 6 Usama Mukwaya: The award-winning filmmaker Usama Mukwaya is a second-year student of Business Administration at Cavendish University. Mukwaya is a Ugandan screenwriter, film di- rector and producer. He was award- Mr. Evans Maganda the Cavendish Univer- ed at the Cavendish University 9th sity Distance Learning Coordinator (center), graduation held on May 28. P.7 briefs NCHE officials on CUU’s capacity to run online programmes. Health ministry outlines Standard Operating Procedures for opening schools P.7 The Cavendish Education News MONDAY, AUGUST 3, 2020 2 distance learning. Ms. Museveni also responded to the Blended learning allegations that her ministry was pro- is the way forward hibiting e-learning. “There has been a misconception in the media that the after the pandemic Ministry of Education and Sports pro- ontinuity of teaching and hibited e-learning. This is absolutely learning in universities and not true; we cannot be the ones ban- colleges is a major issue during ning what we are promoting,” Ms C COVID-19. -

Tarehe 12 Aprili, 2011

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA _________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _________ MKUTANO WA TATU Kikao cha Tano – Tarehe 12 Aprili, 2011 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Anne S. Makinda) Alisoma Dua HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati zifuatazo ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU, TAWALA ZA MIKOA NA SERIKALI ZA MITAA (ELIMU): Taarifa ya Mwaka ya Mdhibiti na Mkaguzi Mkuu wa Hesabu za Serikali za Mitaa kwa Mwaka wa Fedha ulioisha tarehe 30 Juni, 2010 (The Annual General Report of the Controller and Auditor General on the Financial Statements of Local Government Authorities for the Financial Year ended 30th June, 2010). NAIBU WAZIRI WA FEDHA (MHE.GREGORY G. TEU): Taarifa ya Mwaka ya Mdhibiti na Mkaguzi Mkuu wa Hesabu za Serikali juu ya Hesabu zilizokaguliwa za Serikali Kuu kwa Mwaka ulioishia tarehe 30 Juni, 2010 (The Annual General Report of the Controller and Auditor General on the Audit of the Financial Statement of the Central Government for the Year ended 30th June, 2010). Taarifa ya Mwaka ya Mdhibiti na Mkaguzi Mkuu wa Hesabu za Serikali juu ya Hesabu zilizokaguliwa za Mashirika ya Umma kwa Mwaka 2009/2010 (The Annual General Report of the Controller and Auditor General on the Financial Statement of Public Authorities and other Bodies for the Financial Year 2009/2010). Taarifa ya Mdhibiti na Mkaguzi Mkuu wa Hesabu za Serikali juu ya Ukaguzi wa Ufanisi na Upembuzi kwa kipindi kilichoishia tarehe 31 Machi, 2011 (The General Report of the Controller and Auditor General on the Performance and Forensic Audit Report for the Period ended 31st March, 2011). -

Rwanda's Hutu Extremist Insurgency: an Eyewitness Perspective

Rwanda’s Hutu Extremist Insurgency: An Eyewitness Perspective Richard Orth1 Former US Defense Attaché in Kigali Prior to the signing of the Arusha Accords in August 1993, which ended Rwanda’s three year civil war, Rwandan Hutu extremists had already begun preparations for a genocidal insurgency against the soon-to-be implemented, broad-based transitional government.2 They intended to eliminate all Tutsis and Hutu political moderates, thus ensuring the political control and dominance of Rwanda by the Hutu extremists. In April 1994, civil war reignited in Rwanda and genocide soon followed with the slaughter of 800,000 to 1 million people, primarily Tutsis, but including Hutu political moderates.3 In July 1994 the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) defeated the rump government,4 forcing the flight of approximately 40,000 Forces Armees Rwandaises (FAR) and INTERAHAMWE militia into neighboring Zaire and Tanzania. The majority of Hutu soldiers and militia fled to Zaire. In August 1994, the EX- FAR/INTERAHAMWE began an insurgency from refugee camps in eastern Zaire against the newly established, RPF-dominated, broad-based government. The new government desired to foster national unity. This action signified a juxtaposition of roles: the counterinsurgent Hutu-dominated government and its military, the FAR, becoming insurgents; and the guerrilla RPF leading a broad-based government of national unity and its military, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), becoming the counterinsurgents. The current war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DROC), called by some notable diplomats “Africa’s First World War,” involving the armies of seven countries as well as at least three different Central African insurgent groups, can trace its root cause to the 1994 Rwanda genocide.