Mitl62 Pages.V3 Web.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Concept Music for Low Concept Minds

High concept music for low concept minds Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: August/September New albums reviewed Part 1 Music doesn’t challenge anymore! It doesn’t ask questions, or stimulate. Institutions like the X-Factor, Spotify, EDM and landfill pop chameleons are dominating an important area of culture by churning out identikit pop clones with nothing of substance to say. Opinion is not only frowned upon, it is taboo! By JOHN BITTLES This is why we need musicians like The Black Dog, people who make angry, bitter compositions, highlighting inequality and how fucked we really are. Their new album Neither/Neither is a sonically dense and thrilling listen, capturing the brutal erosion of individuality in an increasingly technological and state-controlled world. In doing so they have somehow created one of the most mesmerising and important albums of the year. Music isn’t just about challenging the system though. Great music comes in a wide variety of formats. Something proven all too well in the rest of the albums reviewed this month. For instance, we also have the experimental pop of Georgia, the hazy chill-out of Nils Frahm, the Vangelis-style urban futurism of Auscultation, the dense electronica of Mueller Roedelius, the deep house grooves of Seb Wildblood and lots, lots more. Somehow though, it seems only fitting to start with the chilling reflection on the modern day systems of state control that is the latest work by UK electronic veterans The Black Dog. Their new album has, seemingly, been created in an attempt to give the dispossessed and repressed the knowledge of who and what the enemy is so they may arm themselves and fight back. -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Education Bureau 2009 The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles Michael Saffle Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form or by any means, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Content 1 The Beatles: An Introduction 1 2 The Beatles as Composers/Performers: A Summary 7 3 Five Representative Songs and Song Pairs by the Beatles 8 3.1 “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me” (1962) 8 3.2 “Michelle” and “Yesterday” (1965) 12 3.3 “Taxman” and “Eleanor Rigby” (1966) 14 3.4 “When I’m Sixty-Four” (1967) 16 3.5 “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” (1967) 18 4 The Beatles: Concluding Observations 21 5 Listening Materials 23 6 Musical Scores 23 7 Reading List 24 8 References for Further Study 25 9 Appendix 27 (Blank Page) 1 The Beatles: An Introduction The Beatles—sometimes referred to as the ‘Fab Four’—have been more influential than any other popular-music ensemble in history. Between 1962, when they made their first recordings, and 1970, when they disbanded, the Beatles drew upon several styles, including rock ‘n’ roll, to produce rock: today a term that almost defines today’s popular music. In 1963 their successes in England as live performers and recording artists inspired Beatlemania, which calls to mind the Lisztomania associated with the spectacular success of Franz Liszt’s 1842 German concert tour. -

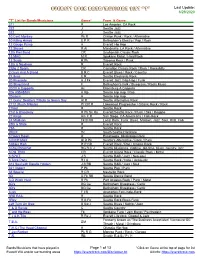

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

1 Persistent Organic Pollutant Burden, Experimental POP Exposure And

1 Title: 2 Persistent organic pollutant burden, experimental POP exposure and tissue properties 3 affect metabolic profiles of blubber from grey seal pups. 4 5 Authors: 6 Kelly J. Robinson1*, Ailsa J. Hall1, Cathy Debier2, Gauthier Eppe3, Jean-Pierre Thomé4 7 and Kimberley A. Bennett5 8 9 Affiliations: 10 1Sea Mammal Research Unit, Scottish Oceans Institute, University of St Andrews 11 2Louvain Institute of Biomolecular Science and Technology, Université Catholique de 12 Louvain 13 3Center for Analytical Research and Technology (CART), B6c, Department of 14 Chemistry, Université de Liège 15 4Center for Analytical Research and Technology (CART), Laboratory of Animal 16 Ecology and Ecotoxicology (LEAE), Université de Liège 17 5Division of Science, School of Science Engineering and Technology, Abertay 18 University 19 20 *Corresponding Author: Kelly J. Robinson, email: [email protected] 21 22 Keywords: 23 Dioxin-like PCBs; glucose uptake; lipolysis; lactate production; blubber depth; 24 energetic state; environmental contamination; fasting; feeding 25 1 26 Abstract 27 Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are toxic, ubiquitous, resist breakdown, 28 bioaccumulate in living tissue and biomagnify in food webs. POPs can also alter energy 29 balance in humans and wildlife. Marine mammals experience high POP concentrations, 30 but consequences for their tissue metabolic characteristics are unknown. We used 31 blubber explants from wild, grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) pups to examine impacts of 32 intrinsic tissue POP burden and acute experimental POP exposure on adipose metabolic 33 characteristics. Glucose use, lactate production and lipolytic rate differed between 34 matched inner and outer blubber explants from the same individuals and between 35 feeding and natural fasting. -

The Transcendent Experience in Experimental Popular Music Performance

The transcendent experience in Experimental Popular Music performance Adrian Brian Barr, B. Mus (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2012 Acknowledgements My wife Elanor, thank you for all your love and support – I know I meant to finish this before we married, but I wouldn’t have it any other way! My parents Robert and Linda Barr; my family Jane, Daniel, Karen and Gene for supporting me through this journey; Matthew Robertson, my brother, great friend and musical ally; friends and colleagues at UWS, particularly Mitchell Hart, Noel Burgess, Eleanor McPhee, John Encarnacao, Samantha Ewart, Michelle Stead; and most importantly my supervisors Diana Blom and Ian Stevenson – thank you ever so much for your hard work and ongoing support. Thank you to all the inspiring musicians who kindly gave me the time to share their amazing experiences. Statement of Authentication This work has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other institution and an undertaking that the work is original and a result of the candidates own research endeavour. Signed: ____________________________ Adrian Barr 1 ABSTRACT The Transcendent Experience in Experimental Popular Music Performance Adrian Barr, B. Mus (Hons.) School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Music This thesis is an investigation into experiences of transcendence in music performance driven by the author’s own performance practice and the experimental popular music environment in which he is situated. Employing a phenomenological approach, 19 interviews were conducted with musicians, both locally and internationally, who were considered strong influences on the author’s own practice. -

Music and Belonging / Musique Et Appartenance

Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance Joint meeting / Congrès mixte Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch Faculty of Music University of Toronto 25-27 May 2017 / 25-27 mai 2017 Welcome / Bienvenue The Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto is pleased to host the conference Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance from May 25th to May 27th, 2017. This meeting brings together four Canadian scholarly societies devoted to music: CAML / ACBM (Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux), CSTM / SCTM (Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales), IASPM Canada (International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch), and MusCan (Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes). We are expecting 300 people to attend the conference. As you will see in this program, there will be scholarly papers (ca. 200 of them), recitals, keynote speeches, workshops, an open mic session and a dance party – something for everyone. The multiple award winning Gryphon Trio will be giving a free recital for conference delegates on Friday evening, May 26th from 7:00 to 8:15 pm. Visitors also have the opportunity to take in many other Toronto events this weekend: music festivals by the Royal Conservatory of Music and CBC; concerts by Norah Jones, Rheostatics, The Weeknd, and the Toronto Symphony; a Toronto Blue Jays baseball game; the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival, and a host of other events at venues large and small across the city. -

State Representatives Share Stories of PA Politics

Volume 46 Issue 4 Student Newspaper Of Shaler Area High School March 2020 State Representativesby James Engel share stories of PA politics Mike Turzai sits at the helm of Pennsylvanian politics, representing the 28th district of the state, which includes several sections of northern Allegh- eny County, including McCandless and Pine Town- ship, since 2001. In 2015, Turzai was elected as the Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representa- tives, a position he still holds. In 2018, Turzai ran in the Republican primary for governor of the state but ultimately suspended his campaign three months lat- er. This year, he announced he would not seek reelec- tion, ending a near 20-year hold of the 28th district. Lori Mizgorski, also a Republican, was elected to represent the 30th district of Pennsylvania, which includes Hampton, Richland, O’Hara, and Shaler townships, as well as part of Fox Chapel, in 2018. Prior to this, she served in several local government positions in the North Hills and Shaler. Mizgorski also served as Chief of Staff to Hal English, the 30th district’s previous representative. She is a graduate State Representative Lori Mizgorski and PA Speaker of the House Mike Turzai answers questions for The Oracle staff of Shaler Area High School and has been a lifelong resident of the area. started from family and community involvement and ships are important and you have to truly focus on Both of these Representatives volunteered their progressed from there. the people of your community and how to make their time for an extended and exclusive question and an- lives better. -

A-Levels Could Be Scrapped in Six Years » Cambridge to Assist in Development of New Diploma » Review in 2013 Will Decide Fate of A-Levels

Reviews: Tiny Dynamite Sport p40 Virgin Full report on Smoker a last gasp Nineteen rugby Eighty- victory for Fashionp20 Four Magdalene Reading between the lines Artsp30 for some vintage outfi ts Issue No 663 Friday October 26 2007 varsity.co.uk e Independent Cambridge Student Newspaper since 1947 A-levels could be scrapped in six years » Cambridge to assist in development of new diploma » Review in 2013 will decide fate of A-levels Camilla Temple Maths and ICT skills, with opportu- undermining academic excellence,” nities to apply their learning in work- he told Varsity. “Whilst a new focus News Editor related contexts.” on vocational subjects is a good thing, Fourteen different diploma quali- creating diplomas for academic sub- Cambridge University is working fi cations will be introduced over the jects is a diversion which can only with the government to design a next three years. Some subjects are weaken the exam system.” new diploma qualifi cation that will to be introduced in September 2008, He added that the Conservative be offered as a widespread alterna- including Construction and the Built Party “supports the reform of voca- tive to A-levels from September Environment, Creative and Media, tional learning to provide an alterna- 2008. If the new diploma is success- and Engineering. Other Diplomas, tive route to employment, but the ful, A-levels could be scrapped in as such as Hair and Beauty, Hospitality new exams announced this week little as six years. and Retail, will follow over the next are designed to subvert GCSEs and The university has voiced its sup- three years. -

Many Great Plays Have Been Adapted for the Silver Screen

J e f f e r s o n P e r f o r m i n g A r t s S o c i e t y Presents JEFFERSON PERFORMING ARTS SOCIETY 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, Louisiana 70001 Phone: 504 885 2000..Fax: 504 885 [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Teacher notes…………….4 Educational Overview……………………..6 History………………………………..7 – 15 Introduction…………………………..16 – 20 More Background…………………......21 - 49 Lesson Plans 1) “1940 - 1960’s: War Years, Rebuilding the World and a Leisure Boom” pg. 50 - 53 2) “Activities, Projects and Drama Exercises” pgs. 54 - 56 3) “A Hard Day’s Night” pgs. 57 - 64 Standards and Benchmarks: English……………….65 – 67 Standards and Benchmarks: Theatre Arts…………68 - 70 5) “The History of Rock and Roll” pgs. 71 - 73 6) “Bang on a Can: The Science of Music” pg. 74 Standards and Benchmarks: Music………………… 75 - 76 Photo gallery pgs. 77-80 2 Web Resource list …………..81 An early incarnation of the Beatles. Michael Ochs Archives, Venice, Calif. IMAGES RETRIEVED FROM: The Beatles, with George Martin of EMI Records, are presented with a silver disc to mark sales of over a quarter million copies of the 1963 British single release of "Please Please Me." Hulton Getty/Liaison Agency Image Retrieved From: http://search.eb.com/britishinvasion/obrinvs048p1.html http://search.eb.com/britishinvasion/obrinvs045p1.html 3 Teacher notes Welcome to the JPAS production of Yeah, Yeah, Yeah! a concert celebration performed by Pre-Fab 4, Featuring the stars of The Buddy Holly Story. Come together as four lads from across the US rekindle the spirit of yesterday through the music of the world’s most popular band. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION TO EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Saunders | 9781351697583 | | | | | The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music 1st edition PDF Book It includes pieces that move in endless circles. Archived from the original on 23 February Yet within each sound Beuger suggests there are infinite possibilities, so that everything can be contained in the brief moments of activity which characterize his work. Instructions in her scores typically indicate the necessary attitude required to make sounds as a primary focus, or differing forms of documentation are used to enable performers to triangulate her intentions when working with objects. Whilst he is at pains to point out that he does not consider his music experimental, given it is ostensibly result rather than process oriented, this particular concern has much in common with other practitioners in the field. One could argue that there is much terra incognita on the map of twentieth- and twenty-first-century music: it might seem familiar, but whole areas are either underresearched or have largely been ignored. Although I came to know his music well at this time, it was the later experience of working with Tim as a performer which led me to a clearer understanding of his work as a composer. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Finding new things in new or old situations is central to experimentation. In addition, critics have often overstated the simplicity of even early minimalism. Sherburne has suggested that noted similarities between minimal forms of electronic dance music and American minimal music could easily be accidental. -

Day2020.Pdf (4.239Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH Pop Cinema: Aesthetic Conversations between Art and the Moving-Image By Tom Day Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Design Edinburgh College of Art University of Edinburgh December 2019 I Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgment, russthe work presented is entirely my own. Thomas Day December 2019 II Contents Title Page I Declaration II Contents III Abstract IV Acknowledgements VII List of Figures IX Introduction: Cinema