POP ENTRAINMENT Jon Leidecker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecstatic Resilience and So the Party Continues

Ecstatic Resilience And so the party continues. Every night I dance to the triplet hi hat trap boi fantasy. A slow syrup oration, deceptively similar to my code swapped histories–punctuated by an 808. Every night I dance to the sex-laced crescendo as bands make her dance, or the desire for another’s body, as the heart decelerates and drugs slowly seep out of the system, I only want u when I’m coming down or fuck faces. There is a rhythm for everything. attention to each beat of the heart, harder and harder. And the Sensation, conjured by this dance, is void of history, geographic location and pain. It’s a sensation that is without my scars or muscle memory. The “party” is about a moment It is without his trauma of of suspension. Feeling a domestic violence. It is without rigorous sensation in the body, the memory of crack or our a pulsating tip-to-tip. Like 80’s birth. It is without those Paul B Preciado’s Testogel–the small deposits of rage. It is moment it seeps in is palpable. without because even the Like pins and needles all sweat releases something from prickly across the skin’s surface the body. Without–because we and a slow numb that calls are giving everything and to splurge is an act of depletion. I’ve listened to my peers recite remixed versions of the names of the recent fallen, lately. I’ve watched the faces in white spaces as the words leave lips. I moisten my lips to receive these names. -

High Concept Music for Low Concept Minds

High concept music for low concept minds Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: August/September New albums reviewed Part 1 Music doesn’t challenge anymore! It doesn’t ask questions, or stimulate. Institutions like the X-Factor, Spotify, EDM and landfill pop chameleons are dominating an important area of culture by churning out identikit pop clones with nothing of substance to say. Opinion is not only frowned upon, it is taboo! By JOHN BITTLES This is why we need musicians like The Black Dog, people who make angry, bitter compositions, highlighting inequality and how fucked we really are. Their new album Neither/Neither is a sonically dense and thrilling listen, capturing the brutal erosion of individuality in an increasingly technological and state-controlled world. In doing so they have somehow created one of the most mesmerising and important albums of the year. Music isn’t just about challenging the system though. Great music comes in a wide variety of formats. Something proven all too well in the rest of the albums reviewed this month. For instance, we also have the experimental pop of Georgia, the hazy chill-out of Nils Frahm, the Vangelis-style urban futurism of Auscultation, the dense electronica of Mueller Roedelius, the deep house grooves of Seb Wildblood and lots, lots more. Somehow though, it seems only fitting to start with the chilling reflection on the modern day systems of state control that is the latest work by UK electronic veterans The Black Dog. Their new album has, seemingly, been created in an attempt to give the dispossessed and repressed the knowledge of who and what the enemy is so they may arm themselves and fight back. -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

Aww Look at What You Mutha- Fuckas Done Went and Did, Y

stop being an artist. an being stop Printed by GHP Media, West Haven, Connecticut. Haven, West Media, GHP by Printed 51 51 14 and Redemption. and better harden up and stop acting like a lil soft cake soft lil a like acting stop and up harden better The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb R. by Illustrated Genesis of Book The Massachusets: Beacon Press, 2012. 2012. Press, Beacon Massachusets: Haters!’ hats. Haters!’ ‘I ’ Diego Rivera, 1931 Rivera, Diego Swallower’ Sword ‘Champion Clifford, Edith 2009. , From ❤ 81 What Gangs Taught Me About Violence, Drugs, Love, Love, Drugs, Violence, About Me Taught Gangs What beans, you a n***a now so you you so now n***a a you beans, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City a of Building the Showing Fresco a of Making The company my son became familiar with because of their their of because with familiar became son my company ‘ Beanie): is infancy since , , 66 66 38 Jumped In: In: Jumped hologram. reproduced for the cover of Jorja Leap’s Leap’s Jorja of cover the for reproduced Ad for Dirty Ghetto Kids, or DGK, a clothing clothing a DGK, or Kids, Ghetto Dirty for Ad nickname (whose artist the to Bobby from Message session in Prof. Stark’s intermediate drawing class at USC. at class drawing intermediate Stark’s Prof. in session next week, and the whole ‘The pregnant heart is driv- wenty years of this me to myself. I’ve learned, ome company recentlyto possible a usefulseem understandingdoesn’t It of underway. -

Mitl62 Pages.V3 Web.Indd

pioneers and pathbreakers artist’s article @Caltech Art, Science and Technology, 1969–1971 S T e p h e n n o w l i n In 1969, the vision of a handful of professors at California Institute of nological achievements. Marshall McLuhan bombed pop Technology resulted in an initiative to bring artists and scientists together culture with The Medium Is the Message, and the Yale School to “see what happens.” The experiment embodied insurgent notions of of Architecture charted an emerging techno postmodern that era—ideas that would once again become manifest a generation ABSTRACT later in the young 21st century’s art-science fusion. Out of this venture landscape in its 1967 edition of the journal Perspecta 11. It came hints of new visual vocabularies and ways of making, as well was all exciting stuff. as an awareness of fault lines between the two cultures. To one young Virtually none of this was reflected in my classes at CCAC, student who found his way into it, the Caltech experience became a a testament to the difficulty for cumbersome institutions to transforming moment. keep pace with the nimble mischief of social change. So I left my Christmas-card assignment un-silkscreened and de- parted in the middle of a semester. Back in Southern Cali- In 1969 I was a college dropout, having rebounded to Los fornia I went to work for the Pasadena architectural firm of Angeles one semester before I might have graduated from Ladd & Kelsey, which had managed to acquire two of the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) in Oakland, most important West Coast architectural commissions of California. -

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Education Bureau 2009 The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles Michael Saffle Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form or by any means, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Content 1 The Beatles: An Introduction 1 2 The Beatles as Composers/Performers: A Summary 7 3 Five Representative Songs and Song Pairs by the Beatles 8 3.1 “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me” (1962) 8 3.2 “Michelle” and “Yesterday” (1965) 12 3.3 “Taxman” and “Eleanor Rigby” (1966) 14 3.4 “When I’m Sixty-Four” (1967) 16 3.5 “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” (1967) 18 4 The Beatles: Concluding Observations 21 5 Listening Materials 23 6 Musical Scores 23 7 Reading List 24 8 References for Further Study 25 9 Appendix 27 (Blank Page) 1 The Beatles: An Introduction The Beatles—sometimes referred to as the ‘Fab Four’—have been more influential than any other popular-music ensemble in history. Between 1962, when they made their first recordings, and 1970, when they disbanded, the Beatles drew upon several styles, including rock ‘n’ roll, to produce rock: today a term that almost defines today’s popular music. In 1963 their successes in England as live performers and recording artists inspired Beatlemania, which calls to mind the Lisztomania associated with the spectacular success of Franz Liszt’s 1842 German concert tour. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Nass Illmatic

NASS ILLMATIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Gasteier | 144 pages | 18 Jun 2009 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826429070 | English | London, United Kingdom Nass Illmatic PDF Book Retrieved August 19, There are many albums with higher highs than Illmatic, but none with fewer flaws. Genesis Selling England by the Pound. But Nas uses Illmatic as more than a vehicle to escape. Retrieved January 11, Encyclopedia of Popular Music. He was not ready. Since its initial reception, Illmatic has been recognized by writers and music critics as a landmark album in East Coast hip hop. Retrieved December 5, The sequencing is perfect down to "Halftime" ending as the cassette tape clicked. Washington Post. Retrieved December 8, The World Is Yours []. Throughout the s and early s, residents of Queensbridge experienced intense violence, as the housing development was overrun by the crack epidemic. Retrieved October 10, Album Rating: 5. Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Open share drawer. Retrieved on In the next sentence, he remembers dark streets and the noose. My rhymin' is a vitamin held without a capsule. Nass Illmatic Writer Retrieved January 17, Halftime []. Jones N. Over these sounds are two men arguing. All this may sound like melodrama, but it's not just me. I think of crime when I'm in a New York state of mind. Retrieved August 19, Complex Music. It Was Written Harris Publications, Inc. Adam Heimlich of The New York Press comments on the appeal of alternative hip-hop in New York City's music scene , and points out that, "In , there appeared likely to be more money and definitely more cultural rewards in working with Arrested Development or Digable Planets. -

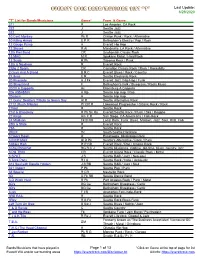

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

"Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 "Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M. Pemberton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES “NOW I AIN’T SAYIN’ SHE’S A GOLD DIGGER”: AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMININITIES IN RAP MUSIC LYRICS By Jennifer M. Pemberton A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Jennifer M. Pemberton defended on March 18, 2008. ______________________________ Patricia Yancey Martin Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Dennis Moore Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Jill Quadagno Committee Member ______________________________ Irene Padavic Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Irene Padavic, Chair, Department of Sociology ___________________________________ David Rasmussen, Dean, College of Social Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my mother, Debra Gore, whose tireless and often thankless dedication to the primary education of children who many in our society have already written off inspires me in ways that she will never know. Thank you for teaching me the importance of education, dedication, and compassion. For my father, Jeffrey Pemberton, whose long and difficult struggle with an unforgiving and cruel disease has helped me to overcome fear of uncertainty and pain. Thank you for instilling in me strength, courage, resilience, and fortitude. -

1 Persistent Organic Pollutant Burden, Experimental POP Exposure And

1 Title: 2 Persistent organic pollutant burden, experimental POP exposure and tissue properties 3 affect metabolic profiles of blubber from grey seal pups. 4 5 Authors: 6 Kelly J. Robinson1*, Ailsa J. Hall1, Cathy Debier2, Gauthier Eppe3, Jean-Pierre Thomé4 7 and Kimberley A. Bennett5 8 9 Affiliations: 10 1Sea Mammal Research Unit, Scottish Oceans Institute, University of St Andrews 11 2Louvain Institute of Biomolecular Science and Technology, Université Catholique de 12 Louvain 13 3Center for Analytical Research and Technology (CART), B6c, Department of 14 Chemistry, Université de Liège 15 4Center for Analytical Research and Technology (CART), Laboratory of Animal 16 Ecology and Ecotoxicology (LEAE), Université de Liège 17 5Division of Science, School of Science Engineering and Technology, Abertay 18 University 19 20 *Corresponding Author: Kelly J. Robinson, email: [email protected] 21 22 Keywords: 23 Dioxin-like PCBs; glucose uptake; lipolysis; lactate production; blubber depth; 24 energetic state; environmental contamination; fasting; feeding 25 1 26 Abstract 27 Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are toxic, ubiquitous, resist breakdown, 28 bioaccumulate in living tissue and biomagnify in food webs. POPs can also alter energy 29 balance in humans and wildlife. Marine mammals experience high POP concentrations, 30 but consequences for their tissue metabolic characteristics are unknown. We used 31 blubber explants from wild, grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) pups to examine impacts of 32 intrinsic tissue POP burden and acute experimental POP exposure on adipose metabolic 33 characteristics. Glucose use, lactate production and lipolytic rate differed between 34 matched inner and outer blubber explants from the same individuals and between 35 feeding and natural fasting. -

The Transcendent Experience in Experimental Popular Music Performance

The transcendent experience in Experimental Popular Music performance Adrian Brian Barr, B. Mus (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2012 Acknowledgements My wife Elanor, thank you for all your love and support – I know I meant to finish this before we married, but I wouldn’t have it any other way! My parents Robert and Linda Barr; my family Jane, Daniel, Karen and Gene for supporting me through this journey; Matthew Robertson, my brother, great friend and musical ally; friends and colleagues at UWS, particularly Mitchell Hart, Noel Burgess, Eleanor McPhee, John Encarnacao, Samantha Ewart, Michelle Stead; and most importantly my supervisors Diana Blom and Ian Stevenson – thank you ever so much for your hard work and ongoing support. Thank you to all the inspiring musicians who kindly gave me the time to share their amazing experiences. Statement of Authentication This work has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other institution and an undertaking that the work is original and a result of the candidates own research endeavour. Signed: ____________________________ Adrian Barr 1 ABSTRACT The Transcendent Experience in Experimental Popular Music Performance Adrian Barr, B. Mus (Hons.) School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Music This thesis is an investigation into experiences of transcendence in music performance driven by the author’s own performance practice and the experimental popular music environment in which he is situated. Employing a phenomenological approach, 19 interviews were conducted with musicians, both locally and internationally, who were considered strong influences on the author’s own practice. -

Music and Belonging / Musique Et Appartenance

Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance Joint meeting / Congrès mixte Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch Faculty of Music University of Toronto 25-27 May 2017 / 25-27 mai 2017 Welcome / Bienvenue The Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto is pleased to host the conference Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance from May 25th to May 27th, 2017. This meeting brings together four Canadian scholarly societies devoted to music: CAML / ACBM (Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux), CSTM / SCTM (Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales), IASPM Canada (International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch), and MusCan (Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes). We are expecting 300 people to attend the conference. As you will see in this program, there will be scholarly papers (ca. 200 of them), recitals, keynote speeches, workshops, an open mic session and a dance party – something for everyone. The multiple award winning Gryphon Trio will be giving a free recital for conference delegates on Friday evening, May 26th from 7:00 to 8:15 pm. Visitors also have the opportunity to take in many other Toronto events this weekend: music festivals by the Royal Conservatory of Music and CBC; concerts by Norah Jones, Rheostatics, The Weeknd, and the Toronto Symphony; a Toronto Blue Jays baseball game; the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival, and a host of other events at venues large and small across the city.