Historic Farmsteads: Preliminary Character Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Kingdom Lesson One: the UK - Building a Picture

The United Kingdom Lesson One: The UK - Building a Picture Locational Knowledge Place Knowledge Key Questions and Ideas Teaching and Learning Resources Activities Interactive: identify Country groupings of ‘British Pupils develop contextual Where is the United Kingdom STARTER: constituent countries of UK, Isles’, ‘United Kingdom’ and knowledge of constituent in the world/in relation to Introduce pupils to blank capital cities, seas and ‘Great Britain’. countries of UK: national Europe? outline of GIANT MAP OF islands, mountains and rivers Capital cities of UK. emblems; population UK classroom display. Use using Names of surrounding seas. totals/characteristics; What are the constituent Interactive online resources http://www.toporopa.eu/en language; customs, iconic countries of the UK? to identify countries, capital landmarks etc. cities, physical, human and Downloads: What is the difference cultural characteristics. Building a picture (PPT) Lesson Plan (MSWORD) Pupils understand the between the UK and The Transfer information using UK Module Fact Sheets for teachers political structure of the UK British Isles and Great laminated symbols to the ‘UK PDF | MSWORD) and the key historical events Britain? Class Map’. UK Trail Map template PDF | that have influenced it. MSWORD UK Trail Instructions Sheet PDF | What does a typical political MAIN ACTIVITY: MSWORD map of the UK look like? Familiarisation with regional UK Happy Families Game PDF | characteristics of the UK MSWORD What seas surround the UK? through ‘UK Trail’ and UK UK population fact sheet PDF | MSWORD Happy Families’ games. What are the names of the Photographs of Iconic Human and Physical Geographical Skills and capital cities of the countries locations to be displayed on Assessment opportunities Geography Fieldwork in the UK? a ‘UK Places Mosaic’. -

Steeplow Cottage Alstonefield | Ashbourne | DE6 2FS STEEPLOW COTTAGE

Steeplow Cottage Alstonefield | Ashbourne | DE6 2FS STEEPLOW COTTAGE Steeplow Cottage is a five- bedroom detached stone cottage located within the conservation area of the Peak District National Park, on the outskirts of the highly sought-after village of Alstonefield. KEY FEATURES Steeplow Cottage is a five-bedroom detached stone cottage The property offers over 2,175 sq. ft. of well-appointed accommodation. The property boasts a covered porch area that leads through to the country style kitchen with beamed ceilings, a fantastic Aga, butler sink, tiled floors, built in cupboards and patio doors leading out to the front garden. Off the kitchen is the siting room with wooden floors, stone feature wall, beamed ceilings, an inglenook fireplace with log burner, and bespoke built in units that provide the room with a sense of warmth and space. The ground floor also includes a dining room with wooden floors and views across the fields that can accommodate large gatherings. Next to the dining room is the utility room which has solid wooden work surfaces, a wall mounted unit, plumbing for a washing machine, space for a dryer and the hot water cylinder and oil-fired central heating boiler. An inner lobby off the main sitting room provides access to the guest cloakroom and the snug which has a door onto the garden. Access to the cellar is from inside the house. SELLER INSIGHT The present owners, Gordon and Angela, enjoyed family holidays in the area and loved it so much that when Steeplow Cottage came onto the market, they decided to make Alstonfield their permanent home. -

MANIFOLD VALLEY AGRICULTURAL SHOW – 11Th August 2012 HANDICRAFTS, ARTS and HOME PRODUCE

MANIFOLD VALLEY AGRICULTURAL SHOW – 11th August 2012 HANDICRAFTS, ARTS AND HOME PRODUCE * Local Entries are invited for the following Classes: Handicrafts 1 A knitted toy 2 A completed item of embroidery Please note that the Judge's 3 A “Diamond Jubilee” cushion decision is final. 4 An item of decoupage depicting “summer” Floral Art 5 A teapot of summer flowers 6 A red, white and blue arrangement 7 An arrangement of roses and foliage Photography 8 Celebration 9 After the event Please provide your own name card Painting if you wish to label your produce 10 Happy memories - in any medium after judging has taken place. 11 A life - in any medium Homecraft 12 Coronation Chicken (gentlemen only) 13 A plate of 5 canapes to reflect the international flavours of the Olympics 14 A cake to celebrate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee 15 An 8” bakewell tart 16 A jar of homemade strawberry jam 17 A jar of homemade piccalli 18 A bottle of homemade white wine 19 A bottle of homemade red wine Home-grown Produce Higher points awarded to eggs that 20 3 white eggs match in size & shape, and that are 21 3 brown eggs 'egg shaped', not elongated or oval. 22 3 duck eggs 23 5 tomatoes on a plate 24 3 beetroot on a plate 25 3 onions, dressed 26 Manifold Top Tray Novice class: A collection of 2 kinds of vegetables from the following: onions, potatoes, broad beans, peas, carrots, tomatoes, runner beans, beetroot, cucumbers, cabbages, cauliflowers, peppers, aubergines, radish, on a tray or board. -

Alstonefield Parish Register, 1538-1812

OCTOBER, 1904, Fifth Issue. a Alstonfield. a ALSTONFIELD. c H am stall Ridware. Staffordshire Staffordshire fldansb IRecjtster S ociety p r e s id e n t : THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH. SampleCounty 1bon. Secretary: ©enerai JEditor: REV. F. J. VVROTTESLEY, VV. P. VV. PH ILLIM O RE, m.a., b.c.l. Denstone Vicarage, Uttoxeter. 124, Chancery Lane, London. Studies V o l u m e I. P a r t IV . D e a n e r y o f A l s t o n ^ i e l d . Hlstonfteld Parish IRegister. P A R T I V ., P a g e s 289— 368. P r i v a t e l y p r i n t e d f o r t h e S taffordshire P a r i s h R e g i s t e r S o c i e t y . A ll Communications respecting the printing and transcription of Registers and the issue of the parts should be addressed to Mr. Phillimore. Kindly Kindly forward unpaid Subscriptions to The Manager, Lloyd’s ChanceryBank, Stafford. Lane, London. Attention is especially directed to Notices within the W rapper. 'J"H E Council has the pleasure of placing in the hands ol Members the fifth instalment of Staffordshire Parish Registers for the present year consisting of portions of the following : — Parish. Deanery. StaffordshireAlstonfield (Part IV.) Alstonfield. M ilwich R ugeley Hamstall Ridware Stafford It is intended that the Parishes of each Deanery shall be bound up together Every Register will, however, be separately paginated so that Members may adopt any other more convenient method of arrangement. -

Part I Background and Summary

PART I BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY Chapter 1 BRITISH STATUTES IN IDSTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The North American plantations were not the earliest over seas possessions of the English Crown; neither were they the first to be treated as separate political entities, distinct from the realm of England. From the time of the Conquest onward, the King of England held -- though not necessarily simultaneously or continuously - a variety of non-English possessions includ ing Normandy, Anjou, the Channel Islands, Wales, Jamaica, Scotland, the Carolinas, New-York, the Barbadoes. These hold ings were not a part of the Kingdom of England but were govern ed by the King of England. During the early medieval period the King would issue such orders for each part of his realm as he saw fit. Even as he tended to confer more and more with the officers of the royal household and with the great lords of England - the group which eventually evolved into the Council out of which came Parliament - with reference to matters re lating to England, he did likewise with matters relating to his non-English possessions.1 Each part of the King's realm had its own peculiar laws and customs, as did the several counties of England. The middle ages thrived on diversity and while the King's writ was acknowledged eventually to run throughout England, there was little effort to eliminate such local practices as did not impinge upon the power of the Crown. The same was true for the non-Eng lish lands. An order for one jurisdictional entity typically was limited to that entity alone; uniformity among the several parts of the King's realm was not considered sufficiently important to overturn existing laws and customs. -

Herefordshire Green Infrastructure Strategy

Green Infrastructure Strategy Herefordshire Local Development Framework February 2010 This page is deliberately left blank CONTENTS Preface PART 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 What is Green Infrastructure? 3 1.3 Aims & Objectives of the Strategy 3 1.4 Report Structure 5 2.0 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE IN CONTEXT 2.1 Origins & Demand for the Strategy 7 2.2 Policy Background & Relationship to Other Plans 7 2.2.1 National Policy 8 2.2.6 Regional Policy 10 2.2.7 Local Policy 10 2.2.8 Biodiversity Action Plan 11 2.2.9 Sustainable Community Strategy 11 2.3 Methodology 11 2.3.1 Identification of Assets 11 2.3.5 Assessment of Deficiencies & Needs 12 2.3.7 Strategic Geographic Tiers – Definition & Distribution 13 2.3.11 Sensitivity & Opportunity 16 2.3.13 Guiding Policies 16 2.3.14 Realising Green Infrastructure – the Delivery Mechanism 17 3.0 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE ASSETS – ISSUES & OPPORTUNITIES 3.1 General 19 3.2 Strategic Geographic Tiers 21 3.3 Natural Systems - Geology 23 - Hydrology 29 - Topography 35 -Biodiversity 41 3.4 Human Influences - Land Use 49 -Access & Movement 55 - Archaeology, Historical & Cultural 63 - Landscape Character 71 - Designated & Accessible Open Space 81 3.5 Natural Resources Summary 91 3.6 Human Influences Summary 91 PART 2 4.0 THE GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE FRAMEWORK 4.1 General 93 4.2 A Vision for Green Infrastructure in Herefordshire 94 4.3 The Green Infrastructure Framework 95 4.3.1 Deficiencies & Needs 95 4.3.6 Strategic Tiers 98 4.3.7 County Vision 100 4.3.8 County Strategic Corridors 100 4.3.9 County Strategic Areas -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

Natural Divisions of England: Discussion Author(S): Thomas Holdich, Dr

Natural Divisions of England: Discussion Author(s): Thomas Holdich, Dr. Unstead, Morley Davies, Dr. Mill, Mr. Hinks and C. B. Fawcett Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 49, No. 2 (Feb., 1917), pp. 135-141 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1779342 Accessed: 27-06-2016 02:59 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 198.91.37.2 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 02:59:14 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms NATURAL DIVISIONS OF ENGLAND: DISCUSSION I35 Province Population in Area in Iooo Persons per Ca ital millions. sq. miles. sq. mile. cP rC-a North England ... 27 5'4 500 Newcastle. ' ? Yorkshire ... 3-8 5'I 750 Leeds. o Lancashire ... 6'I 17'6 4' 4 25'I I390 Manchester. P X Severn ..... 29 4'7 620 Birmingham. Trent .. 21 5'5 380 Nottingham. - . Bristol 3... ... I3 2-8 460 Bristol. g Cornwall and Devon I'o 36 4'I 9'8 240 Plymouth. -

UK Roads Death Toll02

COUNTIES WITH THE MOST DANGEROUS ROADS CALCULATED BY FATAL ACCIDENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PER 10,000 RESIDENTS * Based on an analysis of fatality data gathered by the Department for Transport (United Kingdom) and the Police Service of Northern Ireland over a five-year period (2012-2016) 4.110 2.154 X = Top 25 deadliest counties in the United Kingdom 4 24 Fatal trac accidents Orkney Islands Shetland X.XXX = Fatal trac accidents per 10,000 residents Islands per 10,000 residents ≥ 4.501 = Deadliest county by country 4.001 - 4.500 = Safest county by country 3.501 - 4.000 3.001 - 3.500 2.501 - 3.000 2.602 15 2.001 - 2.500 Na h-Eileanan an Iar 1.751 - 2.000 Scotland 1.501 - 1.750 1.251 - 1.500 Moray 3.509 1.001 - 1.250 3.237 6 8 Aberdeenshire ≤ 1.000 Highland Aberdeen City Top 5 Deadliest Roads 3.251 2.318 7 17 by Number of Perth Angus 3.674 and Kinross 5 Fatal Accidents 34 *Does not include Northern Ireland Argyll 2.665 & Bute 12 Road Total fatal Length Fatalities Fife Stirling trac of road per mile of 36 accidents (miles) carriageway East Lothian (2012-2016) 22 20 30 35 24 25 29 15 13 5 A6 70 282 0.248 16 33 3.057 South 10 16 Lanarkshire Scottish Borders A5 67 181 0.370 East Northern Ireland Ayrshire 2.201 South 2.310 3.211 18 A40 65 262 0.248 23 Ayrshire 9 Causeway Dumfries and Galloway Northumberland Coast & Glens Derry City A38 59 292 0.202 and Strabane Tyne 2.309 4 19 and Wear 6 A1 59 410 0.144 Mid Durham 4.150 Ulster 31 2.631 3 14 Fermanagh 7 Ards and North Down Cumbria and Omagh 3 North Yorkshire 2.040 25 Newry, Mourne and Down East Riding Lancashire of Yorkshire West Yorkshire Map Legend A1 Merseyside Greater 1. -

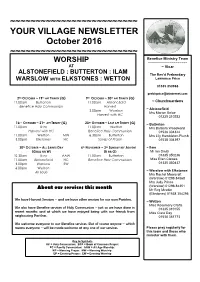

YOUR VILLAGE NEWSLETTER October 2016

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ YOUR VILLAGE NEWSLETTER October 2016 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Benefice Ministry Team WORSHIP ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ AT ~ Vicar B e ALSTONEFIELD : BUTTERTON : ILAM The Rev’d Prebendary n WARSLOW WITH ELKSTONES : WETTON Lawrence Price e 01335 350968 f i [email protected] c 2ND OCTOBER ~ 19TH AFT TRINITY (G) 9TH OCTOBER ~ 20TH AFT TRINITY (G) e 11.00am Butterton 11.00am Alstonefield ~ Churchwardens Benefice Holy Communion Harvest M ~ Alstonefield 3.00pm Warslow i Mrs Marion Beloe Harvest with HC n 01335 310253 i TH ST RD 16 OCTOBER ~ 21 AFT TRINITY (G) 23 OCTOBER ~ LAST AFT TRINITY (G) ~ Butterton s 11.00am Ilam 11.00am Wetton Mrs Barbara Woodward t Harvest with HC Benefice Holy Communion 01538 304324 r 11.00am Wetton MW 6.30pm Butterton Mrs Lily Hambleton-Plumb y 3.00pm Elkstones HC Songs of Praise 01538 304397 T 30TH OCTOBER ~ ALL SAINTS DAY 6TH NOVEMBER ~ 3RD SUNDAY BEF ADVENT ~ Ilam e (GOLD OR W) (R OR G) Mr Ian Smith a 10.30am Ilam AAW 11.00am Butterton 01335 350236 m Miss Ellen Clewes 11.00am Alstonefield HC Benefice Holy Communion ~ 01335 350437 3.00pm Warslow EW ~ 6.00pm Wetton ~ ~ Warslow with Elkstones All Souls ~ Mrs Rachel Moorcroft ~ (Warslow) 01298 84568 ~ Mrs Judy Prince ~ (Warslow) 01298 84351 ~ About our services this month Mr Reg Meakin ~ (Elkstones) 01538 304295 ~ We have Harvest Services – and we have other services for our own Parishes. ~ ~ Wetton ~ Miss Rosemary Crafts ~ We also have Benefice services of Holy Communion – just as we have done in 01335 310155 ~ recent months; and at which we have enjoyed being with our friends from Miss Clare Day ~ neighouring Parishes. -

104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future.