Local Environment Agency Pi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derbyshire and Derby Minerals Plan

CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 4 Background 4 Spatial Context 7 National and Sub-National Aggregate Guidelines 8 2. AGGREGATE RESOURCES 9 Primary Aggregates 9 Secondary and Recycled Aggregates 10 3. ASSESSMENT OF LOCAL RESERVES & PRODUCTION 12 Sand & Gravel Resources & Reserves 12 Recent Production 15 Crushed Rock Resources & Reserves 17 Recent Production 21 Secondary & Recycled Aggregates 23 4. CALCULATING FUTURE PROVISION OF AGGREGATES 25 Future Provision of Sand & Gravel 25 Recent sales 25 Imports and Exports 25 Marine Won Sand and Gravel 27 Supply from adjacent areas 27 Future Economic Growth 28 Conclusions 31 Future Provision of Crushed Rock 33 Recent sales 33 Imports and Exports 33 Supply from adjacent areas 36 Future Economic Growth 36 Progressive Reduction in Quarrying in the Peak Park 37 Conclusions 38 2 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Permitted sand and gravel quarries in Derbyshire 12 Table 2: Sales of sand and gravel in Derbyshire 2006-2015 15 Table 3: Use of sand and gravel 2015 15 Table 4: Active hard rock quarries in Derbyshire & Peak District 19 Table 5: Permitted but inactive hard rock quarries in Derbyshire & the Peak District 20 Table 6: Sales of aggregate crushed rock 2006-2015 22 Table 7: Use of crushed rock 2015 22 Table 8: Distribution of Sand and Gravel from Derbyshire, 2009 26 Table 9: Distribution of Crushed Rock from Derbyshire and Peak District 34 Quarries, 2009 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Derbyshire, Derby and the Peak District National Park 7 Figure 2: Sand and gravel resources in Derby and Derbyshire 14 Figure 3: Sales of sand and gravel in Derbyshire 2006-2015 against past and current provision rate 16 Figure 4: Limestone resources in Derbyshire & the Peak District 18 Figure 5: Sales of aggregate crushed rock 2006-2015 against past and current provision rate 22 Figure 6: Crushed rock inter-regional flows 2009 35 Cover photos: Tunstead and Old Moor Quarry, Buxton and Swarkestone Quarry, Barrow upon Trent 3 1. -

Anroach Farm We Hope You’Ll Love It As Much As We Do

An roach Far m Room guide LOVE IT HERE Welcome to Anroach Farm We hope you’ll love it as much as we do... Windows and Doors If you leave a ground floor window or the door open you may end up meeting one of our friendly cats - ‘Pebbles’ and ‘Henry’. Keeping you Toastie The heater is on a schedule and should be warm enough. To adjust the temperature you can use the up and down arrows on the top right. If you would like to turn the heater off there is a on/off button on the right hand side of the heater. Please do not hang anything on the electric heater as this is a fire risk. What’s on the Box To turn on the Television press the on button situated on the white television remote. Use the top left button on the black remote control to turn on the free sat box and use the guide button to select the programs. There are also radio stations available on the free sat box. There is an in built DVD Player in the TV - it is to the right side of the TV. We have a selection of DVDs at the top of the stairs. If you cannot get the TV to work please check the input source on the TV is set to one of the HDMI inputs. Getting on the Line Can you do without the internet... go on we dare you! If you can’t then you can connect to ‘Anroach Wifi’ (there is no password). -

Steeplow Cottage Alstonefield | Ashbourne | DE6 2FS STEEPLOW COTTAGE

Steeplow Cottage Alstonefield | Ashbourne | DE6 2FS STEEPLOW COTTAGE Steeplow Cottage is a five- bedroom detached stone cottage located within the conservation area of the Peak District National Park, on the outskirts of the highly sought-after village of Alstonefield. KEY FEATURES Steeplow Cottage is a five-bedroom detached stone cottage The property offers over 2,175 sq. ft. of well-appointed accommodation. The property boasts a covered porch area that leads through to the country style kitchen with beamed ceilings, a fantastic Aga, butler sink, tiled floors, built in cupboards and patio doors leading out to the front garden. Off the kitchen is the siting room with wooden floors, stone feature wall, beamed ceilings, an inglenook fireplace with log burner, and bespoke built in units that provide the room with a sense of warmth and space. The ground floor also includes a dining room with wooden floors and views across the fields that can accommodate large gatherings. Next to the dining room is the utility room which has solid wooden work surfaces, a wall mounted unit, plumbing for a washing machine, space for a dryer and the hot water cylinder and oil-fired central heating boiler. An inner lobby off the main sitting room provides access to the guest cloakroom and the snug which has a door onto the garden. Access to the cellar is from inside the house. SELLER INSIGHT The present owners, Gordon and Angela, enjoyed family holidays in the area and loved it so much that when Steeplow Cottage came onto the market, they decided to make Alstonfield their permanent home. -

MANIFOLD VALLEY AGRICULTURAL SHOW – 11Th August 2012 HANDICRAFTS, ARTS and HOME PRODUCE

MANIFOLD VALLEY AGRICULTURAL SHOW – 11th August 2012 HANDICRAFTS, ARTS AND HOME PRODUCE * Local Entries are invited for the following Classes: Handicrafts 1 A knitted toy 2 A completed item of embroidery Please note that the Judge's 3 A “Diamond Jubilee” cushion decision is final. 4 An item of decoupage depicting “summer” Floral Art 5 A teapot of summer flowers 6 A red, white and blue arrangement 7 An arrangement of roses and foliage Photography 8 Celebration 9 After the event Please provide your own name card Painting if you wish to label your produce 10 Happy memories - in any medium after judging has taken place. 11 A life - in any medium Homecraft 12 Coronation Chicken (gentlemen only) 13 A plate of 5 canapes to reflect the international flavours of the Olympics 14 A cake to celebrate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee 15 An 8” bakewell tart 16 A jar of homemade strawberry jam 17 A jar of homemade piccalli 18 A bottle of homemade white wine 19 A bottle of homemade red wine Home-grown Produce Higher points awarded to eggs that 20 3 white eggs match in size & shape, and that are 21 3 brown eggs 'egg shaped', not elongated or oval. 22 3 duck eggs 23 5 tomatoes on a plate 24 3 beetroot on a plate 25 3 onions, dressed 26 Manifold Top Tray Novice class: A collection of 2 kinds of vegetables from the following: onions, potatoes, broad beans, peas, carrots, tomatoes, runner beans, beetroot, cucumbers, cabbages, cauliflowers, peppers, aubergines, radish, on a tray or board. -

Alstonefield Parish Register, 1538-1812

OCTOBER, 1904, Fifth Issue. a Alstonfield. a ALSTONFIELD. c H am stall Ridware. Staffordshire Staffordshire fldansb IRecjtster S ociety p r e s id e n t : THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH. SampleCounty 1bon. Secretary: ©enerai JEditor: REV. F. J. VVROTTESLEY, VV. P. VV. PH ILLIM O RE, m.a., b.c.l. Denstone Vicarage, Uttoxeter. 124, Chancery Lane, London. Studies V o l u m e I. P a r t IV . D e a n e r y o f A l s t o n ^ i e l d . Hlstonfteld Parish IRegister. P A R T I V ., P a g e s 289— 368. P r i v a t e l y p r i n t e d f o r t h e S taffordshire P a r i s h R e g i s t e r S o c i e t y . A ll Communications respecting the printing and transcription of Registers and the issue of the parts should be addressed to Mr. Phillimore. Kindly Kindly forward unpaid Subscriptions to The Manager, Lloyd’s ChanceryBank, Stafford. Lane, London. Attention is especially directed to Notices within the W rapper. 'J"H E Council has the pleasure of placing in the hands ol Members the fifth instalment of Staffordshire Parish Registers for the present year consisting of portions of the following : — Parish. Deanery. StaffordshireAlstonfield (Part IV.) Alstonfield. M ilwich R ugeley Hamstall Ridware Stafford It is intended that the Parishes of each Deanery shall be bound up together Every Register will, however, be separately paginated so that Members may adopt any other more convenient method of arrangement. -

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council October 2020 The ‘rules’ followed were; Max 34 Cllrs, Target 1806 electors per Cllr, use of existing parishes, wards should Total contain contiguous parishes, with retention of existing Cllr total 34 61392 Electorate 61392 Parish ward boundaries where possible. Electorate Ward Av per Ward Parishes 2026 Total Deviation Cllr Ashbourne North Ashbourne Belle Vue 1566 Ashbourne Parkside 1054 Ashbourne North expands to include adjacent village Offcote & Underwood 420 settlements, as is inevitable in the general process of Mappleton 125 ward reduction. Thorpe and Fenny Bentley are not Bradley 265 immediately adjacent but will have Ashbourne as their Thorpe 139 focus for shops & services. Their vicar lives in 2 Fenny Bentley 140 3709 97 1855 Ashbourne. Ashbourne South has been grossly under represented Ashbourne South Ashbourne Hilltop 2808 for several years. The two core parishes are too large Ashbourne St Oswald 2062 to be represented by 2 Cllrs so it must become 3 and Clifton & Compton 422 as a consequence there needs to be an incorporation of Osmaston 122 rural parishes into this new, large ward. All will look Yeldersley 167 to Ashbourne as their source of services. 3 Edlaston & Wyaston 190 5771 353 1924 Norbury Snelston 160 Yeaveley 249 Rodsley 91 This is an expanded ‘exisitng Norbury’ ward. Most Shirley 207 will be dependent on larger settlements for services. Norbury & Roston 241 The enlargement is consistent with the reduction in Marston Montgomery 391 wards from 39 to 34 Cubley 204 Boylestone 161 Hungry Bentley 51 Alkmonton 60 1 Somersal Herbert 71 1886 80 1886 Doveridge & Sudbury Doveridge 1598 This ward is too large for one Cllr but we can see no 1 Sudbury 350 1948 142 1948 simple solution. -

Lowland Derbyshire Biodiversity Action Plan 2011-2020

Published by the Lowland Derbyshire Biodiversity Partnership 2011 Biodiversity Lowland 2011 Derbyshire ‐ 2020 Action Plan Contents Click links to go the various sections of the LBAP Section Quick start Guide Introduction Generic Action Plan Area Action Plans and Targets Action Area 1: Magnesian Limestone Action Area 2: Rother and Doe Lea Valleys Action Area 3: Peak Fringe Action Area 4: Erewash Valley Action Area 5: Claylands Action Area 6: Derby Action Area 7: Trent and Dove Valleys Action Area 8: National Forest area Cumulative Targets UK Priority Habitats—Background Information Farmland Grassland Heathland Wetland Woodland List of Lowland Derbyshire LBAP Partners Appendix 1: Detailed Maps of All Eight Action Areas (with Priority Habitats) these are available as eight 4MB files on CD or from www.derbyshirebiodiversity.org.uk Cover photos, clockwise from top left: Bulfinch. Credit: Laura Whitehead White Admiral. Credit: Debbie Alston Green Lane, north‐east Derbyshire. Credit: Debbie Alston www.derbyshirebiodiversity.org.uk Quick Start Guide 2 Quick Start Guide This Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP) covers the Lowland Derbyshire region for the period 2011 to 2020. It identifies the basic actions we must collectively take if we are to protect and enhance the key biodiversity of this region. The UK Government recognises its international obligations and the economic urgency to protect biodiversity and ecosystems. This LBAP is part of that delivery and local reporting mechanism. Only those habitats and species meeting the UKBAP definitions of ‘Priority Habitat’ or ‘Priority Species’ are included in the targets for the Lowland Derbyshire Action Plans. The history and rationale behind the Local Biodiversity Action Plan is given in the Introduction. -

B H I J Q L K M O N a E C D G

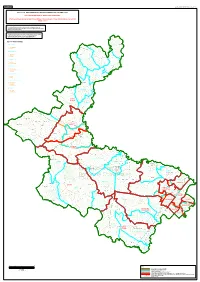

SHEET 1, MAP 1 East_Staffordshire:Sheet 1 :Map 1: iteration 1_D THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EAST STAFFORDSHIRE Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of East Staffordshire June 2020 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. KEY TO PARISH WARDS BURTON CP A ST PETER'S OKEOVER CP B TOWN OUTWOODS CP C CENTRAL D NORTH E SOUTH STANTON CP SHOBNALL CP WOOTTON CP F CANAL G OAKS WOOD MAYFIELD CP STAPENHILL CP RAMSHORN CP H ST PETER'S I STANTON ROAD J VILLAGE UTTOXETER CP ELLASTONE CP K HEATH L TOWN UTTOXETER RURAL CP M BRAMSHALL N LOXLEY O STRAMSHALL WINSHILL CP DENSTONE CP P VILLAGE Q WATERLOO ABBEY & WEAVER CROXDEN CP ROCESTER CP O UTTOXETER NORTH LEIGH CP K M UTTOXETER RURAL CP UTTOXETER CP L UTTOXETER SOUTH N MARCHINGTON CP KINGSTONE CP DRAYCOTT IN THE CLAY CP CROWN TUTBURY CP ROLLESTON ON DOVE CP HANBURY CP DOVE STRETTON CP NEWBOROUGH CP STRETTON C D BAGOTS OUTWOODS CP ABBOTS ANSLOW CP HORNINGLOW BROMLEY CP & OUTWOODS BLITHFIELD CP HORNINGLOW B AND ETON CP E BURTON & ETON G F BURTON CP P SHOBNALL WINSHILL WINSHILL CP SHOBNALL CP HOAR CROSS CP TATENHILL CP Q A BRIZLINCOTE BRANSTON CP ANGLESEY BRIZLINCOTE CP CP BRANSTON & ANGLESEY NEEDWOOD H STAPENHILL I STAPENHILL CP J DUNSTALL CP YOXALL CP BARTON & YOXALL BARTON-UNDER-NEEDWOOD CP WYCHNOR CP 01 2 4 KEY BOROUGH COUNCIL BOUNDARY Kilometres PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY 1 cm = 0.3819 km PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY BAGOTS PROPOSED WARD NAME WINSHILL CP PARISH NAME. -

Derbyshire Dales Local Plan Post

Derbyshire Dales Local Plan – Post-Submission Modifications Habitats Regulations Report Prepared on behalf of: Derbyshire Dales District Council Date: June 2017 Prepared by: ClearLead Consulting Limited The Barn, Cadhay, Ottery St Mary, Devon, EX11 1QT, UK 01404 814273 Contract Number: C0018 Contract No: C0018 Issue: 5 Author V Pearson (signature): Project Director J Mitchell (signature): Date: June 2017 Version Control Record Issue Status Date Reviewer Initials Author Initials 1 Draft 21/03/16 JM VP 2 Version for consultation 05/04/16 JM VP 3 Pre Submission Local Plan 22/08/16 JM VP version 4 Submission Local Plan version 13/12/16 JM VP 5 Post-Submission version 21/06/17 JRP VP This report has been prepared by ClearLead Consulting, Limited (ClearLead) with all reasonable skill, care and diligence. This report is confidential to the Client named on the front of this report and is protected by copyright for intellectual property. This report has been prepared at the Client’s instruction and in accordance with the Services and the Terms agreed between ClearLead and the Client. ClearLead accepts no responsibility whatsoever to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known, unless formally agreed by ClearLead beforehand. Any such party relies upon the report at their own risk. ClearLead disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the Services. Derbyshire Dales Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Report Table of Contents Glossary..................................................................................................................................... 4 Report Addendum ...................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The need for HRA ....................................................................................................... -

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications

Printed On 24/08/2020 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 34/2020 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 17/08/2020 TO 21/08/2020 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 409,604.00 : 322,105.00 P/2020/00844 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Prior Approval - Class Q (Agricultural to Dwellin Ward(s): Bagots Prior Approval for the conversion of agricultural building to form dwelling. Proposed barn conversion For Mr Elsout and Ms Hall Ashbrook Farm c/o JMI Planning Orange Lane 62 Carter Street Bromley Hurst Uttoxeter Abbots Bromley ST14 8EU Staffordshire WS15 3AX REFERENCE Grid Ref: 425,208.00 : 323,700.00 P/2020/00679 Parish(s): Burton Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): Burton Conversion and alterations of two detached buildings to provide 165 apartments and studios Nos 1 & 2 The Maltings For Maltings Developments Limited Wetmore Road c/o Thorne Architecture Limited Burton Upon Trent The Creative Industries Centre Staffordshire Wolverhampton Science Park DE14 1SF Glaisher Drive WOLVERHAMPTON WV10 9TG Page 1 of 10 Printed On 24/08/2020 Weekly List ESBC LIST No: 34/2020 REFERENCE Grid Ref: -

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire, and Their Descendants 1600-1915

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire & their descendants 1600-1915 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS OF DERBYSHIRE, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 by Linda Moffatt 2nd edition by Linda Moffatt© March 2016 1st edition by Linda Moffatt© 2015 This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and omissions, alternative interpretations of the early families, additional information for consideration for future updates. She can be contacted at [email protected] DATES Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

44 Cannock Chase

West Midlands Ringing Group Email: [email protected] Website: www.westmidlandsringinggroup.co.uk Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2 CONTENTS Foreword _________________________________________________________________ 3 Introduction to WMRG ____________________________________________ 4 Ringing Projects _________________________________________________ 5 Thermal Technology & Ringing ____________________________________ 11 Annual Highlights _______________________________________________ 15 The Ringing Year __________________________________________________________ 15 Spring___________________________________________________________________ 15 Summer _________________________________________________________________ 17 Autumn__________________________________________________________________ 18 Our Ringing Sites __________________________________________________________ 20 Marsh Lane ______________________________________________________________ 21 Cannock Chase ___________________________________________________________ 22 Severn Trent _____________________________________________________________ 23 Staffordshire, Shropshire and West Midlands Farms ______________________________ 24 Stone ___________________________________________________________________ 25 Pattingham _______________________________________________________________ 26 Lower Drayton Farm _______________________________________________________ 27 Flaxley Green ____________________________________________________________ 28 Trent Valley Meadows ______________________________________________________