Diptera: Aschiza)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dipterists Forum

BULLETIN OF THE Dipterists Forum Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 Affiliated to the British Entomological and Natural History Society Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 ISSN 1358-5029 Editorial panel Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Assistant Editor Judy Webb Dipterists Forum Officers Chairman Martin Drake Vice Chairman Stuart Ball Secretary John Kramer Meetings Treasurer Howard Bentley Please use the Booking Form included in this Bulletin or downloaded from our Membership Sec. John Showers website Field Meetings Sec. Roger Morris Field Meetings Indoor Meetings Sec. Duncan Sivell Roger Morris 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 1QE Publicity Officer Erica McAlister [email protected] Conservation Officer Rob Wolton Workshops & Indoor Meetings Organiser Duncan Sivell Ordinary Members Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD [email protected] Chris Spilling, Malcolm Smart, Mick Parker Nathan Medd, John Ismay, vacancy Bulletin contributions Unelected Members Please refer to guide notes in this Bulletin for details of how to contribute and send your material to both of the following: Dipterists Digest Editor Peter Chandler Dipterists Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Secretary 122, Link Road, Anstey, Charnwood, Leicestershire LE7 7BX. John Kramer Tel. 0116 212 5075 31 Ash Tree Road, Oadby, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE2 5TE. [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Editor Treasurer Judy Webb Howard Bentley 2 Dorchester Court, Blenheim Road, Kidlington, Oxon. OX5 2JT. 37, Biddenden Close, Bearsted, Maidstone, Kent. ME15 8JP Tel. 01865 377487 Tel. 01622 739452 [email protected] [email protected] Conservation Dipterists Digest contributions Robert Wolton Locks Park Farm, Hatherleigh, Oakhampton, Devon EX20 3LZ Dipterists Digest Editor Tel. -

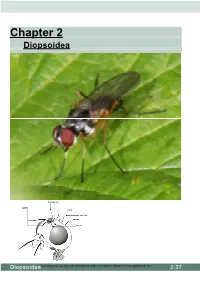

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea DiopsoideaTeaching material only, not intended for wider circulation. [email protected] 2:37 Diptera: Acalyptrates DIOPSOI D EA 50: Tanypezidae 53 ------ Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus very slightly projecting ventrally; male with small stout black setae on hind trochanter and posterior base of hind femur. Postocellar bristles strong, at least half as long as upper orbital seta; one dorsocentral and three orbital setae present Tanypeza ----------------------------------------- 55 2 spp.; Maine to Alberta and Georgia; Steyskal 1965 ---------- Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus strongly projecting ventrally, about twice as deep as remainder of tarsomere 1 (Fig. 3); male without special setae on hind trochanter and hind femur. Postocellar bristles weak, less than half as long as upper orbital bristle; one to three dor socentral and zero to two orbital bristles present non-British ------------------------------------------ 54 54 ------ Only one orbital bristle present, situated at top of head; one dorsocentral bristle present --------------------- Scipopeza Enderlein Neotropical ---------- Two or three each of orbital and dorsocentral bristles present ---------------------Neotanypeza Hendel Neotropical Tanypeza Fallén, 1820 One species 55 ------ A black species with a silvery patch on the vertex and each side of front of frons. Tho- rax with notopleural depression silvery and pleurae with silvery patches. Palpi black, prominent and flat. Ocellar bristles small; two pairs of fronto orbital bristles; only one (outer) pair of vertical bristles. Frons slightly narrower in the male than in the female, but not with eyes almost touching). Four scutellar, no sternopleural, two postalar and one supra-alar bristles; (the anterior supra-alar bristle not present). Wings with upcurved discal cell (11) as in members of the Micropezidae. -

Diptera: Micropezidae) Érica Sevilha Harterreiten-Souza1,2, José Roberto Pujol-Luz1, and Edison Ryoiti Sujii2,*

Influence of various farmland habitats on abundance of Taeniaptera (Diptera: Micropezidae) Érica Sevilha Harterreiten-Souza1,2, José Roberto Pujol-Luz1, and Edison Ryoiti Sujii2,* Abstract Stilt-legged flies play an important ecological role in the process of decomposition of organic matter and, on occasion, in the biological control of insects. Currently, there are 46 known species of Taeniaptera Macquart (Diptera: Micropezidae), and their occurrence is reported in various environments throughout the tropics. In contrast, population information on their temporal and spatial distribution is scarce in areas of the Cerrado biome in Brazil, where habitats are highly disturbed and fragmented by agricultural practices and, therefore, the abundance of the group may change. This study as- sessed abundance of Taeniaptera species in habitats associated with farmland, and determined the change in abundance throughout the year. The stilt- legged flies were sampled in various habitats, namely, organically produced vegetable crops, fallow areas, agroforestry, and native vegetation associated with 4 farms located in the Federal District. In each habitat, one Malaise trap was installed, which remained in place for 72 h, at 14 d intervals, from Mar 2012 to Feb 2013. In total, 486 individuals were collected and identified as members of the speciesT. lasciva (F.), T. annulata (F.), and Taeniaptera sp. The mean abundance of flies was highest in vegetable crops when compared with other habitats, and the abundance was relatively steady throughout the year. Among the habitats sampled, vegetable crop systems were the most suitable habitats for conserving Taeniaptera species. Key Words: micropezids; Taeniaptera lasciva; Cerrado vegetation; organic vegetable crop; abundance Resumen Las moscas de patas largas juegan un papel ecológico importante en el proceso de descomposición de la materia orgánica y, en ocasiones, en el control biológico de insectos. -

Diptera: Brachycera: Calyptratae) Inferred from Mitochondrial Genomes

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2015 The phylogeny and evolutionary timescale of muscoidea (diptera: brachycera: calyptratae) inferred from mitochondrial genomes Shuangmei Ding China Agricultural University Xuankun Li China Agricultural University Ning Wang China Agricultural University Stephen L. Cameron Queensland University of Technology Meng Mao University of Wollongong, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Ding, Shuangmei; Li, Xuankun; Wang, Ning; Cameron, Stephen L.; Mao, Meng; Wang, Yuyu; Xi, Yuqiang; and Yang, Ding, "The phylogeny and evolutionary timescale of muscoidea (diptera: brachycera: calyptratae) inferred from mitochondrial genomes" (2015). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3178. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3178 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The phylogeny and evolutionary timescale of muscoidea (diptera: brachycera: calyptratae) inferred from mitochondrial genomes Abstract Muscoidea is a significant dipteran clade that includes house flies (Family Muscidae), latrine flies (F. Fannidae), dung flies (F. Scathophagidae) and root maggot flies (F. Anthomyiidae). It is comprised of approximately 7000 described species. The monophyly of the Muscoidea and the precise relationships of muscoids to the closest superfamily the Oestroidea (blow flies, flesh flies etc)e ar both unresolved. Until now mitochondrial (mt) genomes were available for only two of the four muscoid families precluding a thorough test of phylogenetic relationships using this data source. -

Insecta Diptera) in Freshwater (Excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Rüdiger Wagner University of Kassel

Entomology Publications Entomology 2008 Global diversity of dipteran families (Insecta Diptera) in freshwater (excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Rüdiger Wagner University of Kassel Miroslav Barták Czech University of Agriculture Art Borkent Salmon Arm Gregory W. Courtney Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs BoudewPart ofijn the GoBddeeiodivrisersity Commons, Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the TRoyerarle Bestrlgiialan a Indnstit Aquaute of Nticat uErcaol Scienlogyce Cs ommons TheSee nex tompc page forle addte bitioniblaiol agruthorapshic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ ent_pubs/41. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global diversity of dipteran families (Insecta Diptera) in freshwater (excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Abstract Today’s knowledge of worldwide species diversity of 19 families of aquatic Diptera in Continental Waters is presented. Nevertheless, we have to face for certain in most groups a restricted knowledge about distribution, ecology and systematic, -

HOVERFLY NEWSLETTER Dipterists

HOVERFLY NUMBER 41 NEWSLETTER SPRING 2006 Dipterists Forum ISSN 1358-5029 As a new season begins, no doubt we are all hoping for a more productive recording year than we have had in the last three or so. Despite the frustration of recent seasons it is clear that national and international study of hoverflies is in good health, as witnessed by the success of the Leiden symposium and the Recording Scheme’s report (though the conundrum of the decline in UK records of difficult species is mystifying). New readers may wonder why the list of literature references from page 15 onwards covers publications for the year 2000 only. The reason for this is that for several issues nobody was available to compile these lists. Roger Morris kindly agreed to take on this task and to catch up for the missing years. Each newsletter for the present will include a list covering one complete year of the backlog, and since there are two newsletters per year the backlog will gradually be eliminated. Once again I thank all contributors and I welcome articles for future newsletters; these may be sent as email attachments, typed hard copy, manuscript or even dictated by phone, if you wish. Please do not forget the “Interesting Recent Records” feature, which is rather sparse in this issue. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 42 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2006 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email: [email protected], to reach me by 20 June 2006. -

STUDIES CONCERNING SPERM TRANSFER in SOME HIGHER DIPTERA a Thesis Submitted by J.N. POLLOCK, B.Sc., M.Sc., D.I.C., Cert. Ed., Fo

STUDIES CONCERNING SPERM TRANSFER IN SOME HIGHER DIPTERA A thesis submitted by J.N. POLLOCK, B.Sc., M.Sc., D.I.C., Cert. Ed., for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Imperial College Field Station, Silwood Park, Sunninghill, ASCOT, Berkshire. July 1971. CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 SECTION 1. The cumulative mating frequency curve in Lucilia sericata 14 SECTION 2a. The alignment of parts during copulation and the function- 41 al morphology of the phallosome, in Lucilia sericata Meigen (Calliphoridae). 41 SECTION 2b. Lateral phallosome ducts in some Calliphorinae, other than Lucilia sericata. 64 SECTION 3. Test for the mated status of male Lucilia sericata. 71 SECTION 4. Tests on tepa-treated males of Lucilia sericata. 81 SECTION 5. Investigations into the nature, fate and function of the male accessory gland secretion in Lucilia sericata. .00 98 SECTION 6. The phallosome of Sarcophaginae. 116 SECTION 7. Studies on the mating of Glossina Weidermann. 129 SECTION 8. Phallosome structure in the male, and the co-adapted spermathecal ducts of the female, in Merodon equestris (F.) (Syrphidae). 154 SECTION 9. The evolution of sperm transfer mechanisms in the Diptera. 166 APPENDIX 1. A probabilistic approach to the cumulative mating frequency curve. 175 APPENDIX 2. Mating frequency data. 180 APPENDIX 3. The taxonomic position of Glossina. 193 APPENDIX 4. Spermatophores in Bibionidae. 199 SUMMARY 204 REFERENCES 208 1 ABSTRACT A review of the pest status of the flies studied is followed by an appraisal of basic research into the mating behaviour and physiology of higher flies, especially Calliphoridae. -

Fly Times 59

FLY TIMES ISSUE 59, October, 2017 Stephen D. Gaimari, editor Plant Pest Diagnostics Branch California Department of Food & Agriculture 3294 Meadowview Road Sacramento, California 95832, USA Tel: (916) 262-1131 FAX: (916) 262-1190 Email: [email protected] Welcome to the latest issue of Fly Times! As usual, I thank everyone for sending in such interesting articles. I hope you all enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed putting it together. Please let me encourage all of you to consider contributing articles that may be of interest to the Diptera community for the next issue. Fly Times offers a great forum to report on your research activities and to make requests for taxa being studied, as well as to report interesting observations about flies, to discuss new and improved methods, to advertise opportunities for dipterists, to report on or announce meetings relevant to the community, etc., with all the associated digital images you wish to provide. This is also a great placeto report on your interesting (and hopefully fruitful) collecting activities! Really anything fly-related is considered. And of course, thanks very much to Chris Borkent for again assembling the list of Diptera citations since the last Fly Times! The electronic version of the Fly Times continues to be hosted on the North American Dipterists Society website at http://www.nadsdiptera.org/News/FlyTimes/Flyhome.htm. For this issue, I want to again thank all the contributors for sending me such great articles! Feel free to share your opinions or provide ideas on how to improve the newsletter. -

Insect Egg Size and Shape Evolve with Ecology but Not Developmental Rate Samuel H

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1302-4 Insect egg size and shape evolve with ecology but not developmental rate Samuel H. Church1,4*, Seth Donoughe1,3,4, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros1 & Cassandra G. Extavour1,2* Over the course of evolution, organism size has diversified markedly. Changes in size are thought to have occurred because of developmental, morphological and/or ecological pressures. To perform phylogenetic tests of the potential effects of these pressures, here we generated a dataset of more than ten thousand descriptions of insect eggs, and combined these with genetic and life-history datasets. We show that, across eight orders of magnitude of variation in egg volume, the relationship between size and shape itself evolves, such that previously predicted global patterns of scaling do not adequately explain the diversity in egg shapes. We show that egg size is not correlated with developmental rate and that, for many insects, egg size is not correlated with adult body size. Instead, we find that the evolution of parasitoidism and aquatic oviposition help to explain the diversification in the size and shape of insect eggs. Our study suggests that where eggs are laid, rather than universal allometric constants, underlies the evolution of insect egg size and shape. Size is a fundamental factor in many biological processes. The size of an 526 families and every currently described extant hexapod order24 organism may affect interactions both with other organisms and with (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). We combined this dataset with the environment1,2, it scales with features of morphology and physi- backbone hexapod phylogenies25,26 that we enriched to include taxa ology3, and larger animals often have higher fitness4. -

Diptera: Sarcophagidae)

Anchored hybrid enrichment challenges the traditional classification of flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Buenaventura, Eliana; Szpila, Krzysztof; Cassel, Brian K.; Wiegmann, Brian M.; Pape, Thomas Published in: Systematic Entomology DOI: 10.1111/syen.12395 Publication date: 2020 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Buenaventura, E., Szpila, K., Cassel, B. K., Wiegmann, B. M., & Pape, T. (2020). Anchored hybrid enrichment challenges the traditional classification of flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Systematic Entomology, 45(2), 281-301. https://doi.org/10.1111/syen.12395 Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 Systematic Entomology (2020), 45, 281–301 DOI: 10.1111/syen.12395 Anchored hybrid enrichment challenges the traditional classification of flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) ELIANA BUENAVENTURA1,2 , KRZYSZTOF SZPILA3 , BRIAN K. CASSEL4, BRIAN M. WIEGMANN4 and THOMAS PAPE5 1Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Berlin, Germany, 2National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, U.S.A., 3Department of Ecology and Biogeography, Faculty of Biological and Veterinary Sciences, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun,´ Poland, 4Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, U.S.A. and 5Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, Copenhagen, Denmark Abstract. Sarcophagidae is one of the most species-rich families within -

Zootaxa, Diptera, Phoridae

Zootaxa 593: 1–11 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 593 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA phylogeny of critical genera of Phoridae (Diptera) and related families of Aschiza CHARLES E. COOK1 , JEREMY J. AUSTIN2 & R. HENRY L. DISNEY1,3 1 Department and Museum of Zoology, University of Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, ENGLAND. Email: [email protected] 2 The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, ENGLAND. (Current address: Sciences Department, Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666E, Melbourne VIC 3001, Australia. Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] Abstract Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA gene sequences supports the monophyly of the Phoridae. Within this family the Phorinae clade includes two aberrant termitophilous subfam- ilies, the Thaumatoxeninae and the Termitoxeniinae, which cluster with Dohrniphora and Diplonevra. These two genera include termitophiles and parasitoids of termites, so we hypothesize that these termitophilous phorids are a monophyletic group. While the data neither refute nor sup- port the assumed monophyly of the Metopininae, the genera of this subfamily were not monophyl- etic in our analysis, but fell into two subclades that correspond with the tribes Metopinini and Gymnophorini. Key words: Diptera, Aschiza, Phoridae, rRNA sequences, phylogeny, maximum likelihood, Baye- sian phylogeny, mitochondria, mtDNA, 12S, 16S lsuRNA, ssuRNA Introduction The flies, midges, and gnats (Diptera) are a successful and widespread insect order that includes over 120 named families and over 140,000 named species. However, the majority of species still remain undescribed and unnamed. -

A Review of the Status of the Lonchopteridae, Platypezidae and Opetiidae Flies of Great Britain

Natural England Commissioned Report NECR246 A review of the status of the Lonchopteridae, Platypezidae and Opetiidae flies of Great Britain Species Status No. 34 First published 29th January 2018 www.gov.uk/natural -england Foreword Natural England commission a range of reports from external contractors to provide evidence and advice to assist us in delivering our duties. The views in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Natural England. Background Making good decisions to conserve species This report should be cited as: should primarily be based upon an objective process of determining the degree of threat to CHANDLER, P.J. 2017. A review of the status the survival of a species. The recognised of the Lonchopteridae, Platypezidae and international approach to undertaking this is by Opetiidae flies of Great Britain Natural England assigning the species to one of the IUCN threat Commissioned Reports, Number246. categories. This report was commissioned to update part of the 1991 review of the scarce and threatened flies of Great Britain Part 2: Nematocera and Aschiza not dealt with by Falk, edited by Falk and Chandler. This original volume included a range of families, but rather than repeat the rather large and arbitrary grouping, the Lonchopteridae, Platypezidae and Opetiidae flies were abstracted into the current review volume. Many of the remaining families will form subsequent volumes in their own right. Natural England Project Manager - David Heaver, Senior Invertebrate Specialist [email protected] Contractor - Peter Chandler Keywords - Lonchopteridae, Platypezidae, Opetiidae files, invertebrates, red list, IUCN, status reviews, IUCN threat categories, GB rarity status Further information This report can be downloaded from the Natural England Access to Evidence Catalogue: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/ .