Emergent Stateness: Critical Urban Geopolitics in Slavutych, EWJUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�24(98) June 12, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 13443 Ministry of Health of Ukraine procurement procedures 7 Hrushevskoho St., 01601 Kyiv Chervatiuk Volodymyr Viktorovych tel.: (044) 253–26–08; 13431 National Children’s Specialized Hospital e–mail: [email protected] “Okhmatdyt” of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 28/1 Chornovola St., 01135 Kyiv www.tender.me.gov.ua Povorozniuk Volodymyr Stepanovych Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications (Imiglucerase in flasks, tel.: (044) 236–30–05 400 units), 319 pcs. Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: 29 Berezniakivska St., 02098 Kyiv; during 2012 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications, 72 lots Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 138 Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; July – December 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 138 Procurement procedure: open tender 29.06.2012 10:00 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 138 economics department 29.06.2012 12:00 Submission: at the customer’s address, economics department Tender security: bank guarantee, deposit, UAH 260000 26.06.2012 10:00 Terms of submission: 90 days; not returned according to part 3, article 24 of the Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office of the deputy general Law on Public Procurement director of economic issues Additional information: For additional information, please, call at 26.06.2012 11:00 tel.: (044) 253–26–08, 226–20–86. -

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities

THE CONGRESS Appendix OF LOCAL AND REGIONAL T�e Sl�vut��� Appe�l AUTHORITIES l�un��ed �� t�e Inte�n�tion�l �onfe�en�e “��e�no��l 20 �e��s on lo��l �nd �egion�l �ut�o�ities de�ling wit� dis�ste�s” Resolution 215 (2006)1 Slavutych (Ukraine), 2-4 March 2006 on ��e�no��l 20 �e������s on lo��l We, �nd �egion�l �ut�o�ities de�ling wit� dis�ste�s The participants in the International Conference “Chernobyl, 20 years on: local and regional authorities dealing with disasters”, local and regional elected representatives, parliamentarians and representatives of . The date of 26 April 2006 marked the 20th anniversary governments, international and non-governmental of the unprecedented catastrophe in the history of mankind organisations and experts, which took place at the Chernobyl nuclear power station. Meeting in Slavutych on the 20th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, 2. The consequences of the Chernobyl disaster have long been a subject of speculation and the issue is a no less Resolve to adopt an appeal, which will be forwarded to the topical subject today, which is why the Congress decided to Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council hold a conference on “Chernobyl, 20 years on: local and of Europe and to other interested organisations. regional authorities dealing with disasters” in Slavutych in Ukraine, from 2 to 4 March 2006. Here in Slavutych, some 50 kilometres from Chernobyl and twenty years after the worst technological disaster in the history of humankind, we feel the need to solemnly 3. -

Too Much to Handle Radioactive Waste Management in the Post Nuclear Accident Country Ukraine

Too much to handle Radioactive waste management in the post nuclear accident country Ukraine Kyiv, 2017 Too much to handle Radioactive waste management in the post nuclear accident country Ukraine Olexi Pasyuk Centre of Environmental Initiatives ‘Ecoaction’ www.ecoaction.org.ua [email protected] This paper is a contribution to the publication: Achim Brunnengräber, Maria Rosaria Di Nucci, Ana María Isidoro Losada, Lutz Mez, Miranda Schreurs (Eds.). Nuclear Waste Governance: An International Comparison. Vol. II, to ap- pear in Springer VS, c. 300 pp We gratefully acknowledge language editing effort by Jess Wallach. Abstract In 1986, Ukraine experienced a major nuclear accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant (NPP); over three decades later, this event continues to define Ukraine’s waste management situation. Today, radioactive waste at the Chornobyl NPP site and surrounding exclusion zone constitutes over 98% of total solid radioactive waste. Spent nuclear fuel is excluded from this figure as it has special legal status and is not considered to be radioactive waste. Following Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union, its institutional system to manage nuclear waste problems has continually changed and has not reached the state of clear responsibilities and distribution of roles between various institutions. However, the need for this clarity is recognized by experts and proposals have been made to centralise the management system. EU and IAEA funding enables research on the waste management system most suitable for Ukraine, including deep geological disposal (DGD), regulatory system improvements and physical infrastructure. Adaptation of the Ukrainian standards and practices to the European standards will be ac- celerated in view of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. -

Securing the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone Against Illegal Movement of Radioactive Materials

Securing the Chornobyl exclusion zone against illegal movement of radioactive materials Oleg O. Bondarenko1, Mykola I. Proskura2, Klaus E. Duftschmid3, Nikolay E. Kravchenko4, 1 SSSIE Ecocentre, 6 Shkilna Street, Chornobyl 07270, Kyiv region, Ukraine, E-mail [email protected] 2 State dept. – Administration of the Chornobyl Exclusion zone, 14 Radyanska Street, Chornobyl 07270, Kyiv region, Ukraine 3 Technical University Graz, Institute for Techn. Physics, 15 Petersgasse, A-8010 Graz, Austria, Consultant to IAEA 4 State Customs Committee of Russian Federation, 11/5 Novozavodskaya, 121087 Moscow, Russia Abstracts. Within the framework of the IAEA Nuclear Security Program the technical cooperation project “Strengthening Security of Nuclear Materials in Ukraine” (UKR/0/008) is aimed primarily to strengthen protection the entrance/exit checkpoints of the Chornobyl exclusion zone and adjacent State borders of Ukraine against illicit movement of radioactive materials (including nuclear materials). The particular situation of the exclusion zone presents a high risk of uncontrolled movement of radioactive materials from and into the exclusion zone. In view of the future construction of the “Shelter-2” and decommissioning of the three closed reactor blocks it is expected that the traffic through the exclusion zone will considerably increase in the next years and those large amounts of possibly contaminated metal scrap, construction material and equipment will leave the zone. There is also a risk of illegal movement of radioactive waste into the zone, possibly also through the international border, which could make the zone to an illegal dumping ground for radioactive waste. As practice shows theft of nuclear materials cannot be excluded. -

We Are, Ukrainians, Took the Nuclear Accident in Japan As Own Tragedy

We are, Ukrainians, took the nuclear accident in Japan as own tragedy, therefore we felt committed to stand side by side with Japan from the first days of this accident and feel obliged to be in Fukushima in the years to come. All Ukrainians know that Japan was one of the first countries that provided relief assistant to new independent state Ukraine to overcome the consequences of Chornobyl accident. 2 An-225 Mriya in Narita (March, 2011.03.23) the largest aircraft in the world made in Ukraine In 25 years, Ukraine was one of the first countries in the world that offered humanitarian aid to Japan. Ukraine is ready to continue providing more governmental support, including humanitarian, expert and technical assistance to Japan based on practical experience in various directions of Ukrainian authorities in minimizing the 3 consequences of Chornobyl disaster. Since 2011/March more than 40 Japanese delegations (parliamentary, governmental, non-governmental, research, professors teams, TEPCO, NRA experts, mass-media) visited Ukraine to explore and study the possibilities of using Ukraine’s experience 4 Around 20 Ukrainian leading post-Chornobyl experts and scientists were invited to Japan to share their knowledge and skills 5 restoration of forecasting of the Chornobyl NPS safe agricultural fields, contamination of water decommission and radiation monitoring systems and scientific transformation into of food on grounded environmental safe contaminated recommendation on system territories water protection measures dosimetric management of control -

Project Factsheet

LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN: ‘SLAVUTYCH IS A GROWTH DRIVER OF OPEN AND FREE ECONOMY OF THE REGION’ Mayors for Economic Growth (M4EG) Pioneer Project PROJECT FACTSHEET The project in a nutshell Timeframe: 2018-2020 Budget: EUR 850,050 (EU contribution - EUR 650,000) Partners: Local authorities of the city of Slavutych and of the municipalities of 7 surrounding communities of the Chernihiv region, SME representatives, representatives of local institutions, enterprises and organizations in the Slavutych region, the “Small Business Laboratory” NGO Geographic coverage: the Slavutych region (25,000 residents) and 7 surrounding communities (2,000 residents): the town of Lyubech and the villages of Nedanchychi, Vedyl’tsi, Dniprovs’ke, Mn’ov, Red’kivka, Karkhivka Target groups: Local authorities of the city of Slavutych and of the municipalities of 7 surrounding communities of the Chernihiv region, local businesses and SME representatives, foreign and local potential investors, local NGOs, civil society organizations and other institutions, local and regional media CONTEXT The city of Slavutych is located in Ukraine’s Kyiv region, and has a population of around 25,000 people. The town is an exclave of the Kyiv region on the territory of the Chernihiv area. Most of the population works at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and for local enterprises. Slavutych’s local authorities began to work on the city’s social and economic development in the early 1990s. The city also began to develop a model of local democracy in 1988. Today Slavutych looks confidently to the future – attracts investments, establishes business support infrastructure, arranges favourable conditions for production of goods and services, creates new jobs. -

Slavutych Atomograd As the Last Ideal City of the USSR: Challenges and Adaptation Mechanisms of Resilience

GeoJournal https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10236-x (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) Slavutych atomograd as the last ideal city of the USSR: Challenges and adaptation mechanisms of resilience Stanley D. Brunn . Olena Dronova . Olena Kononenko Ó Springer Nature B.V. 2020 Abstract Urban resilience implies the ability of all management practices, stimulating innovations in components of a city system to maintain or restore nuclear/alternative energy, IT, and cultural/artistic their functions following unforeseen events, and the events. Urban management and planning systems ability to adapt to external changes. We apply the remain active and are ongoing. concept of resilience and adaptation to Slavutych atomograd following the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Keywords Urban resilience Á Chornobyl nuclear Station explosion. Challenges and responses facing power station Á Urban development threats and the urban management and planning systems are challenges Á Ukraine examined. Perceptions of Slavutych’s resilience capacity are integrated into research based on a survey of residents. The main challenges faced were lack of targeted financing; insufficient economic diversifica- ‘‘Resilience is a complex, multi-dimensional tion and professional employment opportunities; an challenge for urban sustainability planning and aging population and outmigration of youth and design.’’ (Ahern 2011, p.8) professionals; physical remoteness from the Kyiv Region; declining quality of municipal infrastructure, ‘‘Resilience means constantly shedding declining poor housing and community services; and slow industries and replacing them with new ones. It is in introduction of market mechanisms. Resilience poten- the very nature of cities to constantly transform tial formation is used in effective municipal their economic base.’’ (Pole`se 2010,p.13) ‘‘Even though social processes across the globe are increasingly being theorised through a S. -

The Cause of the Chernobyl Accident 1. USSR State Committee on The

NOTES Introduction: The Cause Of The Chernobyl Accident 1. USSR State Committee on the Utilization of Atomic Energy, "The Acci dent at Chernobyl' Nuclear Power Plant and Its Consequences," presented at the International Atomic Energy Agency Post-Accident Review Meeting, Vienna, August 25-29, 1986. 2. USSR State Committee, "The Accident at Chernobyl"; A. Dastur, R. Osborne, D. Pendergast, D. Primeau, V. Snell and D. Torgerson, "A Quick Look at the Post-Accident Review Meeting (PARM)," Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, AECL-9327, September 1986. 3. P.S.W. Chan, A.R. Dastur, S.D. Grant, J.M. Hopwood, and B. Chexal, "The Chernobyl Accident: Multidimensional Simulations to Identify the Role of Design and Operational Features of the RBMK-1000," paper presented to the ENS/ ANS Topical Meeting on Probabilistic Risk Assess ment, Zurich, Switzerland, August 30-September 4, 1987. 4. V.G. Asmolov eta!., "The Accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant: One Year After," preliminary translation of principal Soviet paper presented by N.N. Ponomarev-Stepnoj to the International Atomic Energy Agency International Conference on Nuclear Power Plant Performance and Safety, Vienna, September 28-0ctober 2, 1987. 5. Chan eta!., "The Chernobyl Accident." 6. Ibid. 279 280 Notes 7. V.G. Asmolov et al., "The Accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant." 8. "CANDU Nuclear Generating Station Technical Summary," Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, PA-4, CANDU Operations, Mississauga. 9. V.G. Snell, "Safety of CANDU Nuclear Power stations," Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, AECL-6329, January 1985. 10. For a detailed technical evaluation, see J.Q. Howieson and V.G. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Filozofická Bakalářská Práce Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster and Its Impact on America

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster and its impact on American and British popular culture Jana Lindenbergová Plzeň 2018 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – ruština Bakalářská práce Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster and its impact on American and British popular culture Jana Lindenbergová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Tomáš Hostýnek Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2018 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem práci zpracoval(a) samostatně a pouţil(a) jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2018 ……………………… 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 2. History ............................................................................................................ 2 2.1. Significant places ......................................................................................................... 2 2.2. The Accident ................................................................................................................ 6 2.3. Restoration Process .................................................................................................... 11 3. Effects of Chernobyl disaster ..................................................................... 13 3.1. Politics ...................................................................................................................... -

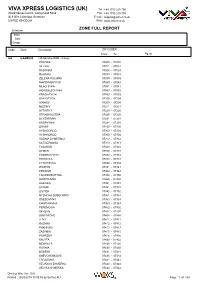

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº4(78) January 24, 2012

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº4(78) January 24, 2012 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 70 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 124 Bulletin No�4(78) January 24, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 01500 Subsidiary Company “Naftogazservice”, procurement procedures NJSC “Naftogaz Ukrainy” 2 Lunacharskoho St., 02002 Kyiv tel.: (067) 444–69–72; 01498 Subsidiary Company “Naftogazservice”, tel./fax: (044) 531–12–57; NJSC “Naftogaz Ukrainy” e–mail: [email protected] 2 Lunacharskoho St., 02002 Kyiv Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: tel.: (067) 444–69–72; www.tender.me.gov.ua tel./fax: (044) 531–12–57; Procurement subject: code 50.30.2 – services in retail trade of parts e–mail: [email protected] and equipment for cars, 2 lots Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; during 2012 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 50.20.1 – services in maintenance and repair Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, reception of passenger cars, 6 lots room Supply/execution: Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast, during 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, reception room Procurement procedure: open tender 20.12.2011 09:30 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s -

Chernobyl 25 Years On

Enhancing nuclear safety Chernobyl 25 years on In late April 1986, a major nuclear accident released a large quantity of radioactive material into the atmosphere… Collection of topics Units Some sources of radiation An introduction to the Chernobyl accident exposure for humans Becquerel The becquerel (Bq) is the unit of Natural Artificial What is radioactivity? ..................................................... p. 2 measurement of radioactivity. radioactivity radioactivity It corresponds to one decay per Abdomen second, for all types of radiation CT scan 1 n The accident ........................................................................ p. 4 emitted ( , , ). Some parts a b g of Brazil and South-West India Gray 2 n Radioactive releases .......................................................... p. 7 The gray (Gy) is the unit of absorbed dose. It corresponds to the quantity of energy La Paz (Bolivia), Average medical 3 n Spread of the radioactive plume over Europe ...... p. 8 (measured in Joules – J) altitude exposure in France transferred by ionising radiation 3660 m (CT scan, X-rays, etc.) to the mass through which it 4 n Radioactive deposits in Europe ................................... p. 12 passes (expressed in kilograms – kg). -1 5 n Contamination of various environments 1 Gy = 1 J.kg . Radon* in France Dental and the food chain ............................................................ p. 17 Sievert panoramic *Naturally X-ray The sievert (Sv) is the unit of occurring n . equivalent dose received by radioactive gas 6 Health impact in the most contaminated areas p. 24 a specific organ or tissue, and the unit of effective (whole Paris-New York 0.06 return flight n body) dose. The equivalent dose 0.006 7 Doses received in France and their is determined from the dose 0.002 associated risks .................................................................