IMMERSED in the ART of FICTION Algonkian Competitive Fiction Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jaines Donahue Nained New" SMC President

The Collegian Volume 110 2012-2013 Article 22 4-9-2013 Volume 110, Number 22 - Tuesday, April 9, 2013 Saint Mary's College of California Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collegian Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Saint Mary's College of California (2013) "Volume 110, Number 22 - Tuesday, April 9, 2013," The Collegian: Vol. 110 , Article 22. Available at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collegian/vol110/iss1/22 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Collegian by an authorized editor of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORAGA, CALIFORNIA VOLUME 110, NUMBE~ TUESDAY, APRIL 9, 2013 STMARYSCOLLEGIAN.COM TWITTER: @ SMC_COLLEGIAN FACEBOOK.COM/SMCCOLLEGIAN -2-Z,, INSIDE THIS Jaines Donahue nained neW" SMC president WEEK'S EDITION First lay .president of Saint Mary's PAGE3 Trevor Project works to College raise suicide awareness announced over Spring Break BY CHARLIE GUESE CHIEF COPY EDITOR At a conference on the Chapel Lawn on March 26, Saint Mary's College officials formally named Dr. James A Donahue of the Grad uate Theological Union as the Col lege's 29th president. Donahue's term as president is effective July 1, 2013. "It's an absolute honor and bless ing to be named the 29th president of Saint Mary's College," Donahue said, "I promise that I will dedicate myself with all that I have to make Saint Mary's College the best aca SPORTS demic institution it can be." Donahue's speech at the an Baseball pummels nouncement ceremony highlight Georgetown ed his excitement at being named President of Saint Mary's, the heritage of the College's history, Prior to his appointment, Do It was announced in June 2012 Brother Ron was appointed Poetry and the all-encompassing Lasal nahue also served on the Advisory that incumbent President Brother president on September 23, 2005. -

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 9 No. 1 September 25, 1998 Back Page Bot-man: License to Chafe Chris Van Dyke, John Holowach Front Page Proposed Performing Arts Center Building Site Angers Neighbors Montgomery Place contends the structure will destroy the continuity of their horizon By David Porter Miller Protested Firing Line Airs, Diversity Debate Continues Spring debate over the ACLU is broadcast, includes Students of Color protest unedited By Anna-Rose Mathieson Boot This! Campaigns Against Brock and Parking Club wants to pay tickets, end Boot, and challenge parking and road policies By Jessica Jacobs Page 2 News Briefs Student Center Hardhat Tours By Nate Schwartz Conference on War Crimes By John Holowach Page 3 Firing Line Episode (continued) Proposed Northern Dutchess Hospital Merger Officially Fails Administrative conflicts will keep Rhinebeck’s hospital a secular institution By Amanda Kniepkamp Earth Coalition Planning Several Events, Initiatives Upcoming: testing Bard’s tap water, a solar oven, campus clean-up efforts Page 4 Student Convocation Fund Budget Allotments, Fall 1998 Page 5 El Más Wicked Info-Revolution Henderson Computer Center’s new boss has a dream: for every community member an “information-technology dialtone” Joe Stanco Page 6 Beer and Circus: Budget Forum ‘98 Another parliamentary morass of drunken debate Leigh Jenco Green Party’s Kovel Asks Voters: Why Not? Former psychiatrist and activist, Bard Social Studies Professor Joel Kovel is running for the New York Senate Susannah E. David and Jeff GiaQuinto Student Association Officers -

Hold My Home Album Download Hold My Home Album Download

hold my home album download Hold my home album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66a107e3eea315e8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Cold War Kids - Hold My Home (Deluxe) (2015) Artist : Cold War Kids Title : Hold My Home (Deluxe) Year Of Release : 2020 Label : Downtown Records Genre : Indie Rock Quality : Mp3 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks) Total Time : 49:57 Total Size : 114 / 328 MB WebSite : Album Preview. 1. All This Could Be Yours (3:08) 2. First (3:20) 3. Hot Coals (3:28) 4. Drive Desperate (4:10) 5. Hotel Anywhere (3:11) 6. Go Quietly (3:51) 7. Nights & Weekends (2:54) 8. Hold My Home (2:50) 9. Flower Drum Song (3:37) 10. Harold Bloom (4:12) 11. Hear My Baby Call (4:51) 12. First (Return to Tackyland) (3:26) 13. All This Could Be Yours (Return to Tackyland) (3:20) 14. -

Cold War Kids: Robbers & Cowards VINYL : Зарубежная Музыка : Виниловые

Cold War Kids: Robbers & Cowards VINYL : Зарубежная музыка : Виниловые Продолжение... Похожие запросы: Cold War Kids: Robbers & Cowards VINYL : Зарубежная музыка : Виниловые A Million Eyes (From Stella Artois - The Chalice Symphony). Hot Coals. Ro Los Angeles' four-piece Cold War Kids recently toured with the Luminee Cold War Kids - Robbers & Cowards CD. Cold War Kids-Robbers Cowards 2006, One of the biggest torrents indexer w.. Robbers & Cowards is the debut studio album by the American indie rock Cold War Kids Robbers & Cowards cd disc image. Download Cold War Kids-Robbers Cowards FLAC torrent or any other torren Libble-Cold War Kids-Behave Yourself EP-2009 1 torrent download locations. Cold War Kids Discography: Albums:-2006 Robbers and Cowards free download.. Cold War Kids. Five Quick Cuts - EP. Mine Is Yours. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for Hospita Torrents for first cold war kids. Download millions of torrents with TV 01:39:21. Cold War Kids - Robbers & Cowards/Loyalty To Loyalty. Hospital beds cold war kids. Cold war kids robbers and cowards download. download game red faction arm.. The best workout songs for running by Cold War Kids by BPM (Page 1) Formed in California in 2004, Cold War Kids released their debut album Robb Robbers & Cowards EP, Cold War Kids - скачать, рецензии, бесплатно, отз из рекламы Fox Hang me up to dry - Cold War Kids. Robbers & Cowards. Cold war kids - vacation - youtube, From album robbers cowards Cold War Kids fourth studio album, 'Dear Miss Lonelyhearts' is th The cold war kids robbers and coward. фотография Cold War Kids. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

Lifelong Learning

CONTINUING AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES Lifelong Learning SEPTEMBER – DECEMBER 2018 www.brookdalecc.edu/lifelonglearning www.facebook.com/BrookdaleLifelongLearning TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Lecture Series ............................................................................................... 2 The Arts .................................................................................................................................... 3 Photography ......................................................................................................................... 5 Creativity Never Retires .................................................................................................. 7 • Holocaust • Broadway! • quantum theory • the Beatles Financial.................................................................................................................................12 Wellness & Fitness Center Classes .........................................................................13 Holistic Health ...................................................................................................................16 Humanities ..........................................................................................................................18 Irish Heritage ......................................................................................................................13 Languages ...........................................................................................................................21 Literature/Writing -

Chants Sacrés

Chants sacrés : Voix de femmes 000 A CHA Chants sacrés : Voix d'hommes 000 A CHA Chants juifs 000 A CHA Raman, Susheela Divas du monde 000 A DIV Drop the debt 000 A DRO Brassens, Echos D'aujourd'hui 000 A ECH Dournon, Geneviève Instruments de musique du monde 000 A INS Je n'aime pas la world, mais ça j'aime bien ! 000 A JEN Konono n°1 Planet Rock 000 A PLA Tziganes 000 A TZI World Music 000 A WOR Bratsch L'Epopée tzigane 000 A.EPO Gotan Project Les Musiques qui ont inspiré leur album 000 A.GOT Waro, Danyel Island blues 000 A.ISL Mondomix Experience 000 A.MON Music from the Wine Lands 000 A.MUS Afonso, José Out of this world 000 A.OUT Sélection musiques du monde 000 A.SEL Son du monde 000 A.SON Voyage en Tziganie 000 A.VOY Bratsch Notes de voyage 000 BRA Bratsch Ca s' fête ! 000 BRA Bratsch Plein du monde 000 BRA Bratsch Urban Bratsch 000 BRA Chemirani, Keyvan Le Rythme de la parole 000 CHE Frères Nardàn (Les) Nardanie Autonome 000 FRE Gurrumul Yunupingu, Geoffrey Rrakala 000 GUR Haïdouti Orkestar Balkan heroes 000 HAI Levy, Hezy Singing like the Jordan river 000 LEV Nu Juwish Music 01 000 NUJ Robin, Thierry Gitans 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Rakhi 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Alezane 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Ces vagues que l'amour soulève 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Anita ! 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Kali Sultana 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Les Rives 000 ROB Robin, Thierry Jaadu 000 ROB Romanès, Délia J'aimerai perdre la tête 000 ROM Socalled Ghetto blaster 000 SOC Taraf de haïdouks Maskarada 000 TAR Tchanelas Les Fils du vent 000 TCH Urs Karpatz Autour de Sarah -

The Flaming Lips 11 Musicians Who Deserve to Be Bigger Than Pitbull * Vol

HAIM + PASSION PIT + COLD WAR KIDS + JESSIE WARE VARIANCETHE SIGHTS + SOUNDS YOU LOVE Phoenix!THE WAIT IS g OVER. JAMES BLAKE #SXSW RUDIMENTAL IN PICS SAM JAEGER 30 YEARS OF JACOB ARTIST THE FLAMING LIPS 11 MUSICIANS WHO DESERVE TO BE BIGGER THAN PITBULL * VOL. 4, ISSUE 2 | APRIL_SPRING 2013 NOW PLAYING KEEP YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION. FOLLOW YOUR DREAM . TATE MUSIC GROUP PRODUCTION DISTRIBUTION MARKETING MEDIA TATEMUSICGROUP.COM FIRST THINGS FIRST to watch this year. Rudimental, Cold War Kids, The Flaming Lips and Passion Pit also grabbed the spot- light down south. James Blake, while he attended the festival, did not per- form, but his forthcoming album, Overgrown, is easily one of the best this year has to offer. We also spotlight some of our TV favorites, including Sam Jaeger, the Parenthood actor that female fans just can’t seem to get enough of, and Jacob Artist, the new eye candy on Fox’s hit dramedy Glee. We also talk- ed to Kevin Alejandro, who co-stars in CBS’s new smash, Golden Boy. Most excitingly, our cover stars one of our favorite bands of the mod- WELCOME, SPRING. ern era, an ensemble whose highly anticipated new album readers vot- AFTER A WHIRLWIND we were there bringing you the ed the spring release they are look- INTRO TO 2013, SPRING latest, behind-the-scenes and up- ing forward to most. Coming off a close. From Mumford and Sons to lengthy period of silence, Phoenix IS HERE AT LAST. fun., we caught up with the big win- returns this month with Bankrupt!, ners and breakout stars. -

The Epistolary Form in Twentieth-Century Fiction

THE EPISTOLARY FORM IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY FICTION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Catherine Gubernatis, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Professor Sebastian D.G. Knowles, Advisor Approved by Professor Brian McHale Professor David Herman ______________________________ Advisor English Graduate Program ABSTRACT In my dissertation, I argue the use of the epistolary form in twentieth-century fiction reflects the major principles of the modern and postmodern literary movements, separating epistolary practices in fiction from their real world counterparts. Letters and letter writing played an important role in the development of the English novel in the middle eighteenth century. A letter is traditionally understood to be a genuine depiction of what the writer is currently feeling, and when used in fiction, letters become a way to represent characters’ internal states and to present accounts of recent events. Thus letters in eighteenth-century fiction establish that language can clearly reveal the subjective experience. The modernists, however, believe that all knowledge, even subjective knowledge, is limited and after World War I, lose confidence in language’s ability to describe the modern era. They revive the epistolary genre and use letters in their works precisely to reject the conventions that had been founded in the eighteenth century. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the use of letters in fiction continues to evolve. Postmodern authors use the epistolary form to investigate the ways language complicates representations of the subjective experience and to explore the letter’s relationship to different states of being. -

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 9 No. 6 April 22, 1999 Page 1 Salman Rushdie Kicks Off National Book Tour at Bard Author shares passages from The Ground Beneath her Feet, discusses its creation, and responds to audience questions Ciprian Iancu Bard-Backed Charter School Proposed New York Charter School Act allows for development of community-run institution Ciprian Iancu New Smolny Blazes Path The college, modeled after Bard, champions progressive education Stephanie Schneider Page 2 Coffee Shop Opens New campus center café opens to limited enthusiasm News Briefs Doggy Takes Dive of Death From Embankment Adina Estreicher Page 3 Pemstein Ready to Rock Since December, new VP of development/alumni/ae affairs has brought big-city expertise to Bard’s fundraising program Peter Malcolm Page 4 Norman Manea and the Triumph of the Artist The acclaimed writer and Bard Professor discusses personal victory in the battle between the artist and the regime Ciprian Iancu Page 6 CCS Spring Shows Present Diverse Works Graduate students bring year-long creative process to end Kerry Chance Art Review [Art Club Show in Fisher] Even Robertson Page 7 Stanley Kubrick is Not Dead, He’s Downloaded D.C. Caudle Page 8 Food Review [Buffet 2000 restaurant review] Stephanie Schneider Creating a New World With Universal Power A Troupe of performers takes on social issues with theatre Stephanie Schneider Page 9 Film Review [Steve Holland Films] Anne Matusiewicz Two Bardians Explore Life in “Hell’s Kitchen” Siblings Samir and Marisa Vural produce drama in NY Andy Varyu Page 10 Miss Lonelyhearts -

Bot-Man According to Some, the New Millenium Began Three Years Ago

BOT-MAN ACCORDING TO SOME, THE NEW MILLENIUM BEGAN THREE YEARS AGO. WE AT BAT-MAN THINK IT'S HIGH TIME SOMEONE NOTICED. SO IN CELEBRATION,WE'D LIKE TO SHOW YOU SOME OLD BOT-MAN'S SPANNING THE YEARS WHICH WERE DUG UP IN THE ARCHIVING PROJECT. TODAY WE TAKE YOU BACK TO BARD IN THE 80'5, IN PART 1 OF: BOT-MAN - Y1.996K <..SOC"\~t)'( ST"ot..€ 1'"Hc C~SE.'lTE -r-f'-'Pt -.....1'1'){Tri f. i,ti. ~ ~ nit. Cor'\ f l)O?. b C.Lf ANl) 'Rt.PLM.£1;) IT 't-lml 'BO'('6lPR tID cu~ a.i.110! le\ ~ -Createdby and copyrightChris Van Dyke &John Hollowach,1999. Specialthanks to Bard Housingfor introducingtkJnns with trailer hitchesinto our lives;Mr. T, for pitying UJ fools; ProfessorSkiff. for prob ably not knowing that Rotman even exists;Alf, for beinga part of the Westerncanon that Harold Bloomforgot to mention;and all my friends,for playing that tediousgame of "Which of thesetwo jokes arefun- _.:,.r+?" PAGE2 The Bard Observer NEWS September 24, 7999 inside the At Home with Range: NEWS Housing Crisis, Fall '99 Bard Charter School Ready to Break New Ground Students copewith "temporary"living conditions page3 Q By Briana Avinia-Tapper E i-"l..'.'!l- A Glimpse into the Mind of Gehry DURING THE FIRST three wet weeks of the ~ page3 Language and Thinking Workshop, white mobile ~ homes sprouted like mushrooms on Bard campus j between the Student Center and th'! Ravines. j The trailers are the hurried adjustment to an unusually large first-year class. -

Order Form Full

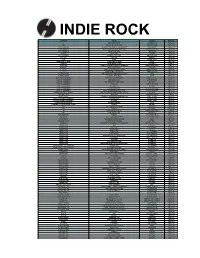

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I.