Goffman, Erving(1963) Stigma. London: Penguin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jaines Donahue Nained New" SMC President

The Collegian Volume 110 2012-2013 Article 22 4-9-2013 Volume 110, Number 22 - Tuesday, April 9, 2013 Saint Mary's College of California Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collegian Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Saint Mary's College of California (2013) "Volume 110, Number 22 - Tuesday, April 9, 2013," The Collegian: Vol. 110 , Article 22. Available at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collegian/vol110/iss1/22 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Collegian by an authorized editor of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORAGA, CALIFORNIA VOLUME 110, NUMBE~ TUESDAY, APRIL 9, 2013 STMARYSCOLLEGIAN.COM TWITTER: @ SMC_COLLEGIAN FACEBOOK.COM/SMCCOLLEGIAN -2-Z,, INSIDE THIS Jaines Donahue nained neW" SMC president WEEK'S EDITION First lay .president of Saint Mary's PAGE3 Trevor Project works to College raise suicide awareness announced over Spring Break BY CHARLIE GUESE CHIEF COPY EDITOR At a conference on the Chapel Lawn on March 26, Saint Mary's College officials formally named Dr. James A Donahue of the Grad uate Theological Union as the Col lege's 29th president. Donahue's term as president is effective July 1, 2013. "It's an absolute honor and bless ing to be named the 29th president of Saint Mary's College," Donahue said, "I promise that I will dedicate myself with all that I have to make Saint Mary's College the best aca SPORTS demic institution it can be." Donahue's speech at the an Baseball pummels nouncement ceremony highlight Georgetown ed his excitement at being named President of Saint Mary's, the heritage of the College's history, Prior to his appointment, Do It was announced in June 2012 Brother Ron was appointed Poetry and the all-encompassing Lasal nahue also served on the Advisory that incumbent President Brother president on September 23, 2005. -

Nastanak I Rana Povijest Izdavačke Kuće Penguin Books

Nastanak i rana povijest izdavačke kuće Penguin Books Brlek, Neven Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:914035 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA INFORMACIJSKE I KOMUNIKACIJSKE ZNANOSTI Ak. god. 2018./2019. Neven Brlek Nastanak i rana povijest izdavačke kuće Penguin Books Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr.sc. Ivana Hebrang Grgić Zagreb, 2019. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Izjavljujem i svojim potpisom potvrĎujem da je ovaj rad rezultat mog vlastitog rada koji se temelji na istraţivanjima te objavljenoj i citiranoj literaturi. Izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije napisan na nedozvoljen način, odnosno da je prepisan iz necitiranog rada, te da nijedan dio rada ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. TakoĎer izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije korišten za bilo koji drugi rad u bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj ili obrazovnoj ustanovi. ______________________ Neven Brlek Sadržaj Sadrţaj........................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Uvod i kontekst ................................................................................................................. -

After the Planners Robert Goodman

a Pelican Original After the Planners Robert Goodman Pelican Books After the Planners Architecture Environment and Planning Robert Goodman is an Associate Professor of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been involved for some considerable time in planning environments for those in the lower income brackets. He is a founder of Urban Planning Aid, and helped to organize The Architect’s Resistance. He has been the critic on architecture for the Boston Globe and his designs and articles have been widely exhibited and published. He is currently researching a project under the patronage of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. John A. D. Palmer is a Town Planner who, after experience in London and Hampshire, left local government to join a small group of professionals forming the Notting Hill Housing Service which works in close association with a number of community groups. He is now a lecturer in the Department of Planning, Polytechnic of Central London, where he is attempting to link the education of planners with the creation of a pool of expertise and information for community groups to draw on. AFTER THE PLANNERS ROBERT GOODMAN PENGUIN BOOKS To Sarah and Julia AND ALL THOSE BRAVE PEOPLE WHO WON’T PUT UP WITH IT Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia First published in the U.S.A. by Simon & Schuster and in Great Britain by Pelican Books 1972 Copyright © Robert Goodman, 1972 Made and printed in Great Britain by Compton Printing Ltd, Aylesbury -

Website Important Books Final Revised Aug2010

Tom Lombardo’s Library: Important Books on Philosophy, Religion, Evolution, Science, Psychology, Science Fiction, and the Future A - C • Abrahamson, Vickie, Meehan, Mary, and Samuel, Larry The Future Ain’t What it Used to Be. New York: Riverhead Books, 1997. • Ackroyd, Peter The Plato Papers: A Prophecy. New York: Doubleday, 1999. • Adams, Douglas The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Ballantine, 1979-2002. • Adams, Fred and Laughlin, Greg The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. New York: The Free Press, 1999. • Adams, Fred Our Living Multiverse: A Book of Genesis in 0+7 Chapters. New York: Pi Press, 2004. • Adler, Alfred Understanding Human Nature. (1927) Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1965. • Aldiss, Brian Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction. New York: Schocken Books, 1973. • Aldiss, Brian and Wingrove, David Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. North Yorkshire, UK: House of Stratus, 1986. • Allman, William Apprentices of Wonder: Inside the Neural Network Revolution. Bantam, 1989. • Amis, Kingsley and Conquest, Robert (Ed.) Spectrum Vols. 1-5. New York: Berkley, 1961-1966. • Ammerman, Robert (Ed.) Classics in Analytic Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965. • Anderson, Poul Brainwave. New York: Ballantine Books, 1954. • Anderson, Poul Time and Stars. New York: Doubleday, 1964. • Anderson, Poul The Horn of Time. New York: Signet Books, 1968. • Anderson, Poul Fire Time. New York: Ballantine Books, 1974. • Anderson, Poul The Boat of a Million Years. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1989. • Anderson, Walter Truett Reality Isn’t What It Used To Be. New York: Harper, 1990. • Anderson, Walter Truett (Ed.) The Truth About the Truth: De-Confusing and Re Constructing the Postmodern World. -

The Extraordinary Flight of Book Publishing's Wingless Bird

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:46 am Page 70 LOGOS The extraordinary flight of book publishing’s wingless bird Eric de Bellaigue “Very few great enterprises like this survive their founder.” The speaker was Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, the year before his death in 1970. Today the company that Lane named after the wingless bird has soared into the stratosphere of the publishing world. How this was achieved, against many obstacles and in the face of many setbacks, invites investigation. Eric de Bellaigue has been When Penguin Books was floated on the studying the past and forecasting Stock Exchange in April 1961, it already had the future of British book twenty-five profitable years behind it. The first ten Penguin reprints, spearheaded by André Maurois’ publishing for thirty-five years. Ariel and Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, In this first instalment of a study came out in 1935 under the imprint of The Bodley of Penguin Books, he has Head, but with Allen Lane and his two brothers combined his financial insights underwriting the venture. In 1936, Penguin Books Limited was incorporated, The Bodley Head having with knowledge gleaned through been placed into voluntary receivership. interviews with many who played The story goes that the choice of the parts in Penguin’s history. cover price was determined by Woolworth’s slogan Subsequent instalments will bring “Nothing over sixpence”. Woolworths did indeed de Bellaigue’s account up to the stock the first ten titles, but Allen Lane attributed his selection of sixpence as equivalent to a packet present day. -

The Culture of Sexuality: Identification, Conceptualization, and Acculturation Processes Within Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Cultures

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 The Culture of Sexuality: Identification, Conceptualization, and Acculturation Processes Within Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Cultures Joshua Glenn Parmenter Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Parmenter, Joshua Glenn, "The Culture of Sexuality: Identification, Conceptualization, and Acculturation Processes Within Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Cultures" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7236. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURE OF SEXUALITY: IDENTIFICATION, CONCEPTUALIZATION, AND ACCULTURATION PROCESSES WITHIN SEXUAL MINORITY AND HETEROSEXUAL CULTURES by Joshua Glenn Parmenter A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE in Psychology Approved: Renee V. Galliher, Ph.D. Melanie M. Domenech Rodríguez, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Melissa Tehee, Ph.D., J.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Joshua Glenn Parmenter All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT The Culture of Sexuality: Conceptualization, Identification, and Acculturation Processes within Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Cultures by Joshua G. Parmenter, Master of Science Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Renee V. Galliher, Ph.D. Department: Psychology Social identity development theories emphasize self-categorization, in which individuals label themselves in order to form a social identity with a particular group. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

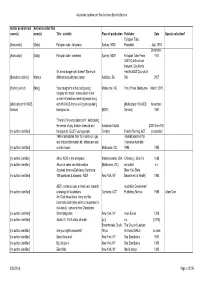

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 9 No. 1 September 25, 1998 Back Page Bot-man: License to Chafe Chris Van Dyke, John Holowach Front Page Proposed Performing Arts Center Building Site Angers Neighbors Montgomery Place contends the structure will destroy the continuity of their horizon By David Porter Miller Protested Firing Line Airs, Diversity Debate Continues Spring debate over the ACLU is broadcast, includes Students of Color protest unedited By Anna-Rose Mathieson Boot This! Campaigns Against Brock and Parking Club wants to pay tickets, end Boot, and challenge parking and road policies By Jessica Jacobs Page 2 News Briefs Student Center Hardhat Tours By Nate Schwartz Conference on War Crimes By John Holowach Page 3 Firing Line Episode (continued) Proposed Northern Dutchess Hospital Merger Officially Fails Administrative conflicts will keep Rhinebeck’s hospital a secular institution By Amanda Kniepkamp Earth Coalition Planning Several Events, Initiatives Upcoming: testing Bard’s tap water, a solar oven, campus clean-up efforts Page 4 Student Convocation Fund Budget Allotments, Fall 1998 Page 5 El Más Wicked Info-Revolution Henderson Computer Center’s new boss has a dream: for every community member an “information-technology dialtone” Joe Stanco Page 6 Beer and Circus: Budget Forum ‘98 Another parliamentary morass of drunken debate Leigh Jenco Green Party’s Kovel Asks Voters: Why Not? Former psychiatrist and activist, Bard Social Studies Professor Joel Kovel is running for the New York Senate Susannah E. David and Jeff GiaQuinto Student Association Officers -

The Stigma of Feminism: Disclosures and Silences Regarding Female Disadvantage in the Video Game Industry in US and Finnish Media Stories

This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Author(s): Kivijärvi, Marke; Sintonen, Teppo Title: The stigma of feminism : disclosures and silences regarding female disadvantage in the video game industry in US and Finnish media stories Year: 2021 Version: Published version Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Rights: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Rights url: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Please cite the original version: Kivijärvi, M., & Sintonen, T. (2021). The stigma of feminism : disclosures and silences regarding female disadvantage in the video game industry in US and Finnish media stories. Feminist Media Studies, Early online. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1878546 Feminist Media Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 The stigma of feminism: disclosures and silences regarding female disadvantage in the video game industry in US and Finnish media stories Marke Kivijärvi & Teppo Sintonen To cite this article: Marke Kivijärvi & Teppo Sintonen (2021): The stigma of feminism: disclosures and silences regarding female disadvantage in the video game industry in US and Finnish media stories, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2021.1878546 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1878546 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: -

IMMERSED in the ART of FICTION Algonkian Competitive Fiction Guide

IMMERSED IN THE ART OF FICTION Algonkian Competitive Fiction Guide I’m told, I forget. I see, I remember. I do, I understand. – Algonkian Proverb _____ _____ Algonkian Writer Conferences 2020 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Suite 443 Washington, DC 20006 1 Copyright 2010, Algonkian Writer Conferences As certain young people practice the piano or the violin four and five hours a day, so I played with my papers and pens ... My literary tasks kept me fully occupied; my apprenticeship at the altar of technique, craft; the devilish intricacies of para- graphing, punctuation, dialogue placement. Not to mention the grand overall design, the great demanding arc of middle- beginning-end. One had to learn so much, and from so many sources ... - Truman Capote 2 Copyright 2010, Algonkian Writer Conferences TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. What The Successful Author Must Possess P. 4 2. Drama’s Most Powerful Elements in The Novel P. 6 3. The Intellectual Trace of Theme P. 22 4. Character Animation Sketching P. 30 5. Plotting and Story Devices P. 41 6. Story Enhancement À La Mr. Graves P. 48 7. Strong Narrative Through Synergy: How to Satisfy The Art of Fiction P. 51 8. Dialogue: Never a Gratuitous Word P. 61 9. Minims of Suspense P. 67 10. Exercises, Guides, and The Perfect Synopsis P. 69 11. Prose Drills and ―The Seven Reasons‖ P. 78 3 Copyright 2010, Algonkian Writer Conferences MORE THAN A PREFACE The primary goal of Algonkian is to provide you with the knowledge it takes to intelligently approach the planning and writing of a first novel. -

Penguin in Southern Africa

Minding Their Own Business: Penguin in Southern Africa ALISTAIR McCLEERY (Edinburgh Napier University) Abstract The primary title of this essay is taken from that of the 1975 Penguin African Library revised edition of Antony Martin’s exposé of (as its subtitle read) Zambia’s struggle against Western control. The essay exploits original archival evidence to highlight Penguin’s distinctive attitudes to and practices within the Southern African market, particularly, but not exclusively, the major market of South Africa. The Penguin African Library itself contained not only many volumes on South Africa and The Struggle for a Birthright (subtitle of a 1966 volume by Mary Benson), but also pioneering works on Portuguese decolonisation, on the Rhodesian question, and on South-West Africa (by Ruth First). The essay adopts the framework of a three-phase development in the motivation behind publishing for Africa: Tutelage, Radicalism, and Marketisation. The first of these phases is represented by the Penguin (Pelican) West African, later simply African, Series; while the later Penguin African Library illustrates the Radicalism of the then editorial standpoint. These African Library mass-market paperbacks had a double intent: to inform Western readers about a region which from the early 1960s dominated international headlines; and to reflect back to increasing numbers of self-aware and educated Africans aspects of the region hidden from them or about which they wished to know more. The degree of opposition to and compromise with colonial and apartheid regimes forms the subject of discussion in the essay as do the reactions in the UK to continuing operations in the region, particularly after the expulsion of South Africa from the Commonwealth in 1961, the adoption of UN Resolution 1 1761 in 1962, and the growth of the Anti-Apartheid Movement throughout the 1960s and 1970s. -

Living with Stigma and Managing Sexual Identity: a Case Study on the Kotis in Dhaka

Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 257-263 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2013.34034 Living with Stigma and Managing Sexual Identity: A Case Study on the Kotis in Dhaka Md. Azmeary Ferdoush University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Received May 15th, 2013; revised August 1st, 2013; accepted August 19th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Md. Azmeary Ferdoush. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is properly cited. Identity as a koti in Dhaka as well as in Bangladesh has always been a stigmatized one. The study aims to explore how the kotis in Dhaka manage their sexual identity and stigma attached with it. To do so eight- een kotis were selected from two areas of Dhaka and unstructured face to face in-depth interviews were conducted. The results show that the kotis in Dhaka have to face numbers of difficulties if their sexual identity is disclosed and knowing or unknowingly they have adopted the stigma management strategies identified by Goffman. Keywords: Koti; Stigma; Identity; Dhaka; Bangladesh Introduction are the first according to him, Individuals who identify them- selves as homosexual or bisexual are found in particular family I tried to act like a normal boy when I was young. Because lines. Monozygotict twins have concordance for non-hetero- everyone told me that I was not acting like a normal boy. My sexuality at about twice the rate of dizygotic twins, suggesting parents used to punish me for my behavior.