ARCHITECTURE AS the PRODUCTION of INTERIORITY a Comprehensive Tool to Understand Interiority in Architecture for an Evolving World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoning ORDINANCE USER's MANUAL

CITY OF PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL PRODUCED BY CAMIROS ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL WHAT IS ZONING? The Zoning Ordinance provides a set of land use and development regulations, organized by zoning district. The Zoning Map identifies the location of the zoning districts, thereby specifying the land use and develop- ment requirements affecting each parcel of land within the City. HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL This User’s Manual is intended to provide a brief overview of the organization of the Providence Zoning Ordinance, the general purpose of the various Articles of the ordinance, and summaries of some of the key ordinance sections -- including zoning districts, uses, parking standards, site development standards, and administration. This manual is for informational purposes only. It should be used as a reference only, and not to determine official zoning regulations or for legal purposes. Please refer to the full Zoning Ordinance and Zoning Map for further information. user'’S MANUAL CONTENTS 1 ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ZONING DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 USES............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N 980314 ZRM Subway

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION July 20, 1998/Calendar No. 3 N 980314 ZRM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the Department of City Planning, pursuant to Section 201 of the New York City Charter, to amend various sections of the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York relating to the establishment of a Special Lower Manhattan District (Article IX, Chapter 1), the elimination of the Special Greenwich Street Development District (Article VIII, Chapter 6), the elimination of the Special South Street Seaport District (Article VIII, Chapter 8), the elimination of the Special Manhattan Landing Development District (Article IX, Chapter 8), and other related sections concerning the reorganization and relocation of certain provisions relating to pedestrian circulation and subway stair relocation requirements and subway improvements. The application for the amendment of the Zoning Resolution was filed by the Department of City Planning on February 4, 1998. The proposed zoning text amendment and a related zoning map amendment would create the Special Lower Manhattan District (LMD), a new special zoning district in the area bounded by the West Street, Broadway, Murray Street, Chambers Street, Centre Street, the centerline of the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River and the Battery Park waterfront. In conjunction with the proposed action, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development is proposing to amend the Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan (located in the existing Special Manhattan Landing District) to reflect the proposed zoning text and map amendments. The proposed zoning text amendment controls would simplify and consolidate regulations into one comprehensive set of controls for Lower Manhattan. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

Lbbert Wayne Wamer a Thesis Presented to the Graduate

I AN ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE USE BUILDING; by lbbert Wayne Wamer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Lehigh University 1982 TABLE OF CCNI'ENTS ABSI'RACI' 1 1. INTRODlCI'ICN 2 2. THE CGJCEPr OF A MULTI-USE BUILDING 3 3. HI8rORY AND GRami OF MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS 6 4. WHY MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS ARE PRACTICAL 11 4.1 CGVNI'GJN REJUVINATICN 11 4. 2 EN'ERGY SAVIN CS 11 4.3 CRIME PREVENTIOO 12 4. 4 VERI'ICAL CANYOO EFFECT 12 4. 5 OVEOCRO'IDING 13 5. DESHN CHARACTERisriCS OF MULTI-USE BUILDINCS 15 5 .1 srRlCI'URAL SYSI'EMS 15 5. 2 AOCHITECI'URAL CHARACTERisriCS 18 5. 3 ELEVATOR CHARACTERisriCS 19 6. PSYCHOI..OCICAL ASPECTS 21 7. CASE srUDIES 24 7 .1 JOHN HANCOCK CENTER 24 7 • 2 WATER TOiVER PlACE 25 7. 3 CITICORP CENTER 27 8. SUMMARY 29 9. GLOSSARY 31 10. TABLES 33 11. FIGJRES 41 12. REFERENCES 59 VITA 63 iii ACKNCMLEI)(}IIENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. Lynn S. Beedle for the supervision of this project and review of this manuscript. Research for this thesis was carried out at the Fritz Engineering Laboratory Library, Mart Science and Engineering Library, and Lindennan Library. The thesis is needed to partially fulfill degree requirenents in Civil Engineering. Dr. Lynn S. Beedle is the Director of Fritz Laboratory and Dr. David VanHom is the Chainnan of the Department of Civil Engineering. The author wishes to thank Betty Sumners, I:olores Rice, and Estella Brueningsen, who are staff menbers in Fritz Lab, for their help in locating infonnation and references. -

Nastanak I Rana Povijest Izdavačke Kuće Penguin Books

Nastanak i rana povijest izdavačke kuće Penguin Books Brlek, Neven Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:914035 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA INFORMACIJSKE I KOMUNIKACIJSKE ZNANOSTI Ak. god. 2018./2019. Neven Brlek Nastanak i rana povijest izdavačke kuće Penguin Books Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr.sc. Ivana Hebrang Grgić Zagreb, 2019. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Izjavljujem i svojim potpisom potvrĎujem da je ovaj rad rezultat mog vlastitog rada koji se temelji na istraţivanjima te objavljenoj i citiranoj literaturi. Izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije napisan na nedozvoljen način, odnosno da je prepisan iz necitiranog rada, te da nijedan dio rada ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. TakoĎer izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije korišten za bilo koji drugi rad u bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj ili obrazovnoj ustanovi. ______________________ Neven Brlek Sadržaj Sadrţaj........................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Uvod i kontekst ................................................................................................................. -

After the Planners Robert Goodman

a Pelican Original After the Planners Robert Goodman Pelican Books After the Planners Architecture Environment and Planning Robert Goodman is an Associate Professor of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been involved for some considerable time in planning environments for those in the lower income brackets. He is a founder of Urban Planning Aid, and helped to organize The Architect’s Resistance. He has been the critic on architecture for the Boston Globe and his designs and articles have been widely exhibited and published. He is currently researching a project under the patronage of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. John A. D. Palmer is a Town Planner who, after experience in London and Hampshire, left local government to join a small group of professionals forming the Notting Hill Housing Service which works in close association with a number of community groups. He is now a lecturer in the Department of Planning, Polytechnic of Central London, where he is attempting to link the education of planners with the creation of a pool of expertise and information for community groups to draw on. AFTER THE PLANNERS ROBERT GOODMAN PENGUIN BOOKS To Sarah and Julia AND ALL THOSE BRAVE PEOPLE WHO WON’T PUT UP WITH IT Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia First published in the U.S.A. by Simon & Schuster and in Great Britain by Pelican Books 1972 Copyright © Robert Goodman, 1972 Made and printed in Great Britain by Compton Printing Ltd, Aylesbury -

Website Important Books Final Revised Aug2010

Tom Lombardo’s Library: Important Books on Philosophy, Religion, Evolution, Science, Psychology, Science Fiction, and the Future A - C • Abrahamson, Vickie, Meehan, Mary, and Samuel, Larry The Future Ain’t What it Used to Be. New York: Riverhead Books, 1997. • Ackroyd, Peter The Plato Papers: A Prophecy. New York: Doubleday, 1999. • Adams, Douglas The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Ballantine, 1979-2002. • Adams, Fred and Laughlin, Greg The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. New York: The Free Press, 1999. • Adams, Fred Our Living Multiverse: A Book of Genesis in 0+7 Chapters. New York: Pi Press, 2004. • Adler, Alfred Understanding Human Nature. (1927) Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1965. • Aldiss, Brian Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction. New York: Schocken Books, 1973. • Aldiss, Brian and Wingrove, David Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. North Yorkshire, UK: House of Stratus, 1986. • Allman, William Apprentices of Wonder: Inside the Neural Network Revolution. Bantam, 1989. • Amis, Kingsley and Conquest, Robert (Ed.) Spectrum Vols. 1-5. New York: Berkley, 1961-1966. • Ammerman, Robert (Ed.) Classics in Analytic Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965. • Anderson, Poul Brainwave. New York: Ballantine Books, 1954. • Anderson, Poul Time and Stars. New York: Doubleday, 1964. • Anderson, Poul The Horn of Time. New York: Signet Books, 1968. • Anderson, Poul Fire Time. New York: Ballantine Books, 1974. • Anderson, Poul The Boat of a Million Years. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1989. • Anderson, Walter Truett Reality Isn’t What It Used To Be. New York: Harper, 1990. • Anderson, Walter Truett (Ed.) The Truth About the Truth: De-Confusing and Re Constructing the Postmodern World. -

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

The Extraordinary Flight of Book Publishing's Wingless Bird

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:46 am Page 70 LOGOS The extraordinary flight of book publishing’s wingless bird Eric de Bellaigue “Very few great enterprises like this survive their founder.” The speaker was Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, the year before his death in 1970. Today the company that Lane named after the wingless bird has soared into the stratosphere of the publishing world. How this was achieved, against many obstacles and in the face of many setbacks, invites investigation. Eric de Bellaigue has been When Penguin Books was floated on the studying the past and forecasting Stock Exchange in April 1961, it already had the future of British book twenty-five profitable years behind it. The first ten Penguin reprints, spearheaded by André Maurois’ publishing for thirty-five years. Ariel and Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, In this first instalment of a study came out in 1935 under the imprint of The Bodley of Penguin Books, he has Head, but with Allen Lane and his two brothers combined his financial insights underwriting the venture. In 1936, Penguin Books Limited was incorporated, The Bodley Head having with knowledge gleaned through been placed into voluntary receivership. interviews with many who played The story goes that the choice of the parts in Penguin’s history. cover price was determined by Woolworth’s slogan Subsequent instalments will bring “Nothing over sixpence”. Woolworths did indeed de Bellaigue’s account up to the stock the first ten titles, but Allen Lane attributed his selection of sixpence as equivalent to a packet present day. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

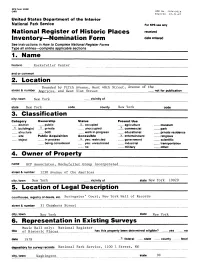

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Height, Setbacks, and Floor Area 17.48

HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA 17.48 Chapter 17.48 – HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA Sections: 17.48.010 Purpose 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.030 Setback Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.040 Floor Area and Floor Area Ratio 17.48.010 Purpose This chapter establishes rules for the measurement of height, setbacks, and floor area, and permitted exceptions to height and setback requirements. 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions A. Measurement of Height. 1. The height of a building is measured as the vertical distance from the assumed ground surface to the highest point of the building. 2. Assumed ground surface means a line on the exterior wall of a building that connects the points where the perimeter of the wall meets the finished grade. See Figure 17.48-1. 3. If grading or fill on a property within five years of an application increases the height of the assumed ground service, height shall be measured using an estimation of the assumed ground surface as it existed prior to the grading or fill. FIGURE 17.48-1: MEASUREMENT OF MAXIMUM PERMITTED BUILDING HEIGHT 48-1 17.48 HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA B. Height Exceptions. Buildings may exceed the maximum permitted height in the applicable zoning district as shown in Table 17.48-1. Note: Height exceptions in Table 17.48-1 below add detail to height exceptions in Section 17.81.070 of the existing Zoning Code. TABLE 17.48-1: ALLOWED PROJECTIONS ABOVE HEIGHT LIMITS Maximum Projection Above Structures Allowed Above Height Limit Maximum Coverage Height Limit Non-habitable decorative features including 3 ft.