Cyprus: Status of U.N. Negotiations and Related Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crux of the Cyprus Problem

PERCEPTIONS JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS September - November 1999 Volume IV - Number 3 THE CRUX OF THE CYPRUS PROBLEM RAUF R. DENKTAŞ His Excellency Rauf R. Denktaş is President of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus Anthony Nutting, who was the British Minister of State at the Foreign Office during the period 1954-56, wrote in his book I Saw for Myself his impression following talks with the leaders of Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots: “There is nothing Cypriot about Cyprus except its name. In this beautiful beleaguered island you are either a Greek or a Turk. From the leaders of the two communities downwards the chasm of suspicion and hatred which separates them is frighteningly wide.”1 EOKA terrorism, which aimed to unite the island with Greece (enosis), was at its height and the Turkish Cypriots, who looked upon enosis as changing colonial masters for the worst, resisted it with every means at their disposal. Hence, the message passed on to all young Greek Cypriots was, “the struggle against the real enemy of our nation and religion, the remnants of the occupying power in Cyprus, will commence as soon as the fight for enosis comes to a successful conclusion”! Any Greek Cypriot who saw the futility and the danger of the drive for enosis, and thus supported independence as a more suitable solution, was regarded as a traitor to the national cause and murdered by EOKA (the Greek Cypriot terrorist organisation). In fact, everyone who opposed enosis was declared an enemy and lived under a constant threat. All Turkish Cypriots were against enosis! By 1957, inter-communal clashes assumed the character of a civil war. -

Raymond Saner

Book chapter in “Unfinished Business”, editor.Guy Olivier Faure, The University of Georgia Press, Atlanta, Georgia and London, 2012. Copyright with Publisher CYPRUS CONFLICT: WILL IT EVER END IN AGREEMENT? Raymond Saner ABSTRACT The goal of this chapter is to describe factors, which have contributed to the persistent failures of peace negotiations on Cyprus. In particular, the author attempts to delineate the impact which multiple and competing external stakeholders (influential foreign powers, supranational institutions, intergovernmental organizations and NGOs from various countries) have had on the peace process and how these third parties (first level GR and TR, secondary level USA, UK, EU and UNO) have used the Cyprus conflict for their own strategic aims and secondary gains by offering their influence to the two conflict parties (Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots). As a result of these ongoing external stakeholders interferences, the Cyprus conflict has persisted and negotiation behavior of the primary conflict parties became characterized by opportunistic tactical maneuvers prolonging and deepening non-agreement ever since the peace enforcing presence of UN forces on the island starting in 1974 and lasting up to the writing of this article. BRIEF SUMMARY OF CYPRUS CONFLICT 2002-JANUARY 2006 1,2 In January 2002, direct talks under the auspices of Secretary-General Annan began between Republic of Cyprus President Glafcos Clerides (Greek community) and Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash (Turkish Community). In November 2002, UN Secretary-General Annan released a comprehensive plan for the resolution of the Cyprus issue. It was revised in early December. In the lead up to the European Union's December 2002 Copenhagen Summit, intensive efforts were made to gain both sides' signatures to the document prior to a decision on the island's EU membership. -

Cyprus Crisis (8)” of the Kissinger- Scowcroft West Wing Office Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 7, folder “Cyprus Crisis (8)” of the Kissinger- Scowcroft West Wing Office Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 7 of The Kissinger-Scowcroft West Wing Office Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Gerald R. Ford Library 1000 Beat ~v.enue . Ann Arbor. Ml 48109-2114 · ·· www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov Withdrawal Sheet for Documents Declassified in Part This.-folder contains a document or documents declassified in part under the Remote Archive Capture (RAC) program. Procedures for Initiating a Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Request The still classified portions of these RAC documents are eligible for MDR. To file a request follow these steps: 1. Obtain the Presidential Libraries Mandatory Review Request Form (NA Form 14020). 2. Complete Sections I, II , and Ill of NA Form 14020. 3. In Section Ill, for each document requested, simply provide the Executive Standard Document Number (ESDN) in the Document Subject!Title or Correspondents column. -

Cyprus - President Clerides” of the National Security Adviser’S Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 1, folder “Cyprus - President Clerides” of the National Security Adviser’s Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 1 of the NSA Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ~ N~TIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ovember 11 Denis Clift believes the attached should be closed out . If the resident: 'vants to 'vrite Clerides at this time, which Denis does not necessarily reco~mend , we 'vould have to start afresh. Close out ---#~~~e ~a-n_n_e Dav ~ Reopen? _________ ~~ SEGRET"- ~ ~/<1JI';,+/ -:: , NAtiONAL SECURITY COUNCIL 11/11/74 MEMORANDUM FOR JEANNE W. DAVIS Jeanne - I believe the chronology of the attached -- ie, 8/28-9/27 is self-evident. It is OBE. If the President wants to write Clerides we will have to start afresh. RECOMMENDATION .· : ~' '', Close out the attache~~ ~ A. Denis Clift \( I lel" eve this one was returned by HAK ask ng that the figures be updated. -

The Inter-Communal Talks and Political Life in Cyprus: 1974- 1983

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 9, No. 3, September 2020 DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v9i3.1973 Citation: Kıralp, Ş. (2020). The Inter-Communal Talks and Political Life in Cyprus: 1974- 1983. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 9(3), 400-414. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v9i3.1973 The Inter-Communal Talks and Political Life in Cyprus: 1974-1983 Şevki Kıralp1 Abstract This paper conducts historical research on the inter-communal talks and the political life in the two communities of Cyprus from 1974 to 1983. The period covered by the research commenced with the creation of the bi-regional structure on the island in 1974 and ceased with the declaration of Turkish Cypriot Independence in 1983. As this period constitutes an important threshold in the history of Cyprus, it might be argued that observing the political developments it covers is likely to be beneficial for the literature. The research focused on the two communities’ positions in negotiations as well as their elections and political actors. It utilized Turkish, Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot newspapers (and official press releases), political leaders’ memoirs, national archives of USA (NARA) as well as official online documents. Its findings indicate that the two sides could not reach to a settlement mainly due to their disagreements on the authorities of central and regional governments. While the Turkish Cypriot side promoted broader authorities for the regional governments, the Greek Cypriot side favoured broader authorities for the central government. On the other hand, while Turkish Cypriot leader Denktaş had managed to unite the majority of Turkish Cypriot right-wing voters, the Greek Cypriot right-wing was divided among supporters of Makarios and Clerides. -

Impediments to the Solution of the Cyprus Problem by Glafcos Clerides

Addressing the Future Impediments to the Solution of the Cyprus Problem by Glafcos Clerides Glafcos Clerides was born in Nicosia, Cyprus, in 1919. He volunteered for the British Royal Air Force in World War II. After his airplane was shot down over Germany in 1942, he remained a prisoner until the end of the war. He received his L.L.B. degree from King’s College, University of Lon- don, in 1948. Among the positions he has held are president of the Cyprus Red Cross, leader of the Democratic Rally Party, and head of numerous delegations addressing the Cyprus problem. He was elected president of the Republic of Cyprus in 1993 and reelected in 1998. He addressed the Se- ton Hall University community on September 24, 1999. At the outset, I would like to say to the students of the School of Diplomacy who I met today—don’t be disappointed because you will hear how difficult it is to solve a simple problem. In order to grasp the meaning and the difficulties we face in trying to solve the Cyprus problem, I should give you a very short background of how it came about. Then I will tell you about the situation: the difficulties that were created by military operations and by the invasion of Cyprus. And finally, I will try to give you my feel- ings about the future and how the problem could be solved. Cyprus has a very strategic position in the eastern Mediterranean. Most nations from Europe who wanted to conquer Africa or Asia stepped over Cyprus, and most Asian nations who wanted to conquer European countries, again, stepped over Cy- prus. -

THE CYPRUS REVIEW a Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues

V O L U M E 2 2 N U M B E R 2 THE CYPRUS REVIEW A Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues The Cyprus Review, a Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues, P.O. Box 24005 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus. Telephone: 22-353702 ext 301, 22-841500 E-mail: [email protected] Telefax: 22-353682, 22-357481, www.unic.ac.cy To access site: > Research > UNic Publications Subscription Office: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2010 University of Nicosia, Cyprus. ISSN 1015-2881. All rights reserved. No restrictions on photo-copying. Quotations from The Cyprus Review are welcome, but acknowledgement of the source must be given. TCR Editorial Team Guest Editor: Costas M. Constantinou Editor in Chief: Hubert Faustmann Co-Editors: James Ker-Lindsay Craig Webster Book Reviews Editor: Olga Demetriou Managing Editor: Nicos Peristianis Assistant Editor: Christina McRoy EDITORIAL BOARD V O L U M E 2 2 N U M B E R 2 Costas M. Constantinou University of Nicosia, Cyprus Ayla Gürel Cyprus Centre of International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO) Maria Hadjipavlou University of Cyprus Mete Hatay Cyprus Centre of International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO) Yiannis E. Ioannou University of Cyprus Joseph Joseph University of Cyprus Michael Kammas Director General, Association of Cyprus Commercial Banks Erol Kaymak Political Science Association, Cyprus Diana Markides University of Cyprus Caesar Mavratsas University of Cyprus Farid Mirbagheri University of Nicosia, Cyprus Maria Roussou The Pedagogical Institute of Cyprus / Ministry of Education & Culture, Cyprus Nicos Trimikliniotis Centre for the Study of Migration, Inter-ethnic and Labour Relations/ University of Nicosia and PRIO Cyprus Centre INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD V O L U M E 2 2 N U M B E R 2 Peter Allen John T.A. -

Cyprus Country Reports on Human Rights Practices

Cyprus Page 1 of 13 Cyprus Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 Prior to 1974, Cyprus experienced a long period of intercommunal strife between its Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. In response the U.N. Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) began operations in March 1964. The island has been divided since the Turkish military intervention of 1974, following a coup d'etat directed from Greece. Since 1974 the southern part of the island has been under the control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus. The northern part is ruled by a Turkish Cypriot administration. In 1983 that administration proclaimed itself the "Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus" ("TRNC"). The "TRNC" is not recognized by the United States or any country except Turkey. A buffer zone patrolled by the UNFICYP separates the two parts. A substantial number of Turkish troops remained on the island. Glafcos Clerides was reelected President of the Republic of Cyprus in 1998. In April 2000, following the first round of Turkish Cypriot elections, Rauf Denktash was declared "President" after "Prime Minister" Dervish Eroglu withdrew. The judiciary is generally independent in both communities. Police in the government-controlled area and the Turkish Cypriot community were responsible for law enforcement. Police forces in the government-controlled area were under civilian control, while the Turkish Cypriot police forces were under military authority. Some members of the police on both sides committed abuses. Both Cypriot economies operated on the basis of free market principles, although there were significant administrative controls in each community. -

The Cyprus Referendum: an Island Divided by Mutual Mistrust

TheAmerican Cyprus Foreign Referendum Policy Interests, 26: 341–351, 2004 341 Copyright © 2004 NCAFP 1080-3920/04 $12.00 + .08 DOI:10.1080/10803920490502755 The Cyprus Referendum: An Island Divided by Mutual Mistrust Viola Drath he people of Cyprus have spoken. And as In his letter to the secretary general dated Toften happens in the annals of history, when- June 7, 2004, Papadopoulos reprimanded Kofi ever bold designs for grand solutions to conten- Annan for allowing those whom he had entrusted tious and complex issues such as the unification with the role of “honest brokers” to become “ac- of Cyprus, devised in secret by powerful political tive participants” throughout the process. elites, are subjected to the free-will decision of a “Through this report they assess effectively the free people, the experts suffered a surprise. The outcome of their own effort while at the same time international community was stunned not so attempting to portray and evaluate the attitude much by the defeat of the referendum on the of the parties involved. In other words, the au- warmed-over final settlement plan proposed by thors of the report play essentially the role of UN Secretary General Kofi Annan; there had judge and jury in the overall outcome of the ne- been signs of impending failure. Contrary to gen- gotiation process they presided over.” eral prognostications, however, it was not the When efforts to reach a settlement on the re- Turkish Cypriots, usually maligned for allegedly unification of Cyprus failed during the last round impeding a peaceful resolution of the Cyprus of negotiations in Buergenstock at the end of question, but the Greek Cypriots who resound- March, in the presence of Greek Prime Minister ingly rejected the referendum on the reunifica- Costas Karamanlis and Turkish Prime Minister tion of the island. -

Title Items-In-Cyprus - Country Files - Greece

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 71 Date 15/06/2006 Time 9:27:37 AM S-0903-0004-04-00001 Expanded Number S-0903-0004-04-00001 Title items-in-Cyprus - country files - Greece Date Created 21/07/1975 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0903-0004: Peackeeping - Cyprus 1971-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit 393 LONDON 119 19 16. 15 GMT £ I!il KOMMIPRESS K £•' tv- -, s-.r- ,/fM^^t- (-i ,v - ,-• il UNLONo393 AKATANI POWELL GALENOVICH HO CHANG PRZYLUCKI ROCHA IHFO"USGS GUYER URQUHART REPEATED TO YACOU3 UNFICYP FROM FOPOVIC» RE PRZYLUCKI 635 QUESTION OF ANY NEW UK CYPRUS INITIATIVES RAISED IN COMMONS 17 DECEMBER. FOREIGN SECRETARY . - ' . * =• i= CALLAGHAN REPLIED HE HAD DISCUSSED AT LENGTH CYPRUS PROBLEM • WITH GREEK-TURKISH MINISTERS IN BRUSSELS PREVIOUS WEEK. " IN COURSE DISCUSSIONS QUOTE CERTAIN PROPOSALS WERE AGREED AS BASIS FOR RESUMPTION OF IHTERCOMMUMAL TALKS BETWEEN CLERIDES-DENKTASH, THESE TALKS WILL BEGIN AGAIN IN HEU YEAR .'.... EYE ADH£RE_TO MY VIEW ..» THAT BEST PROGRESS WILL BE ACHIEVED BETWEEN THE LEADERS OF GREEK CYPRIOT p»3/ '?'.,• "' '••V;., : '.:'•'.- }\-' •:••• '• ' '•• ' ' COMMUNITY AND TURKISH CYPRIOT COMMUNITY WITH DR. WALDHEIM ALSO IN ATTENDANCE AT THE DISCUSSIONS. UNQUOTE= LONOMNIPRESS-H- -»3). 393 635 17 ^ '.••";;.V"''£-i--'•"•'• 'j;*^.'•;*.!'"•;'••'• -i-^f •"."•;••» ".-.'.N v-^. :'•.. v •' '.-IV ;"••:••''••'''.'•*.- ...'•'-'•.•".•>'•: /••i'7 ^•- • • ' ' • -•• '• -••••••• • •••• '•.'-•••'••.•'•••• '-•- I -.•" ^:;r.^;^k? •:'.'••",;;- -d.:-^ *V.:.; .y^ ;•• ;'i:•',::•'•'• ':'<-'^:;;"iV •'y:;^'':;,;.;: ••.•;'' /;v-:-^ ."rrfifiir'V. v v n •-• j « - .•i Q ;"r £J EPfl443 'J r V' ut rpr-'-piis=-• ;v w ;_ U sji j ri ST 5T i f *; i f - ?1 TrnS T — vEC ''i 3 f, i?P;;TFR H P I^NfiRY'.S'GREEHENT.- Wfi t-:::" l':i: ~ i i ~ f: -1 r ~: rt T T i*j ii "- fi :~ T : t i~ . -

An Economic Vision for Cyprus: the Greek Cypriot Experience

AN ECONOMIC VISION FOR CYPRUS: THE GREEK CYPRIOT EXPERIENCE In the last four years, the world’s major powers and the UN aspired to a final solution to one of the most intractable problems of our times, the Cyprus Problem. The effort culminated in disappointment as both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities went their separate ways in the referendum. Despite political talk of a solution, economics is carving a different course for the Island’s communities. Two disengaged economies have grown up separately and are getting used to it. If this is allowed to continue a political solution will not be possible. The challenge for the Greek Cypriot community is to include in its visions the economy of the Turkish Cypriot community without overshadowing it but allow it to grow under one federal umbrella in the EU ‘independently together’. Greek Cypriots and Cyprus as a whole urgently needs new political minds fresh and free from the heavy hand of history George Stavri The author studied Political Science at Stanford University with Condoleezza Rice and is currently the British EU Presidency's Officer in Cyprus. hen the Republic of Cyprus achieved full membership in the EU on May 1st 2004, barriers to trade and previous ways of handling economic affairs with the outside world disappeared. Since the Island gained its Windependence from the disintegrating British Empire in 1960, Cyprus has done well even in the midst of occasional political and military crises that would interrupt its steady economic growth. It has, over the years, used various protectionist policies that benefited producers of various goods, as it allowed favorable terms of trade for the small island economy. -

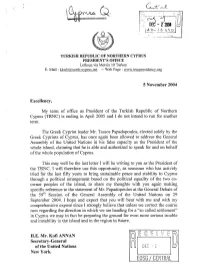

E Island, Claiming That He Is Able and Authorized to Speak for and on Behalf of the Whole Population of Cyprus

DEC- . ••ffAL TURKISH REPUBLIC OF NORTHERN CYPRUS PRESIDENT'S OFFICE Lefkosa via Mersin 10 Turkey E. Mail: [email protected] - Web Page : www.trncpresidency.org 5 November 2004 Excellency, My term of office as President of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) is ending in April 2005 and I do not intend to run for another term. The Greek Cypriot leader Mr. Tassos Papadopoulos, elected solely by the Greek Cypriots of Cyprus, has once again been allowed to address the General Assembly of the United Nations in his false capacity as the President of the whole island, claiming that he is able and authorized to speak for and on behalf of the whole population of Cyprus. This may well be the last letter I will be writing to you as the President of the TRNC. I will therefore use this opportunity, as someone who has actively tried for the last fifty years to bring sustainable peace and stability to Cyprus through a political arrangement based on the political equality of the two co- owner peoples of the island, to share my thoughts with you again making specific reference to the statement of Mr. Papadopoulos at the General Debate of the 59th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations on 29 September 2004. I hope and expect that you will bear with me and with my comprehensive expose since I strongly believe that unless we correct the course now regarding the direction in which we are heading for a "so called settlement" in Cyprus we may in fact be preparing the ground for even more serious trouble and instability in the island and in the region in future.