3.4 Splitting the Atom: Post-Cinematic Articulations of Sound and Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

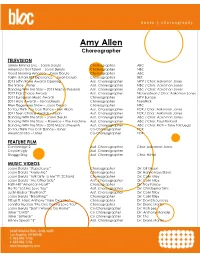

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Committee Oks Bergin's As Landmark

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • WeHo considers budget. pg. 3 Partly cloudy, • Alan Arkin with highs in honored pg. 12 the mid 70s Volume 29 No. 24 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hancock Park and Wilshire Communities June 13, 2019 La Brea Tar Pits next on Thousands #JustUnite in West Hollywood Museum Row revamp n Organizers will now look ahead to next By edwin folven ed is poised to undergo major year’s landmark 50th changes in the coming years. Black liquid tar has been bub- Dr. Lori Bettison-Varga, presi- anniversary of Pride bling up through the Earth’s surface dent and director of the Natural near present-day Wilshire History Museums of Los Angeles By luke harold Boulevard and Curson Avenue for County, which oversees operations millions of years. With that history at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum Under the theme #JustUnite, and its scientific importance in (formerly the George C. Page thousands of people attended the mind, the famous site where La 49th annual LA Pride festival Brea Tar Pits and Museum is locat- See Tar Pits page 26 and parade June 8-9 in West Hollywood. The celebration started Friday with a free ceremony and concert in West Hollywood Park head- lined by Paula Abdul. Festival- goers flooded the park and San Vicente Boulevard Saturday and Sunday to see a musical lineup photo by Luke Harold including Meghan Trainor, Pride was on parade Sunday morning, with local council members, law Ashanti and Years & Years. enforcement, corporate sponsors and other groups riding in floats. “Pride has been something I’ve wanted to play for a long just have a good time.” Angeles City Councilman Mitch time,” said Saro, a recording The annual Pride events have O’Farrell on a float during artist who performed in the Pride become a joyous celebration Sunday’s parade. -

The Case of Rihanna: Erotic Violence and Black Female Desire

Fleetwood_Fleetwood 8/15/2013 10:52 PM Page 419 Nicole R. Fleetwood The Case of Rihanna: Erotic Violence and Black Female Desire Note: This article was drafted prior to Rihanna and Chris Brown’s public reconciliation, though their rekindled romance supports many of the arguments outlined herein. Fig. 1: Cover of Esquire, November 2011 issue, U. S. Edition. Photograph by Russell James. he November 2011 issue of Esquire magazine declares Rihanna “the sexiest Twoman alive.” On the cover, Rihanna poses nude with one leg propped, blocking view of her breast and crotch. The entertainer stares out provocatively, with mouth slightly ajar. Seaweed clings to her glistening body. A small gun tattooed under her right arm directs attention to her partially revealed breast. Rihanna’s hands brace her body, and her nails dig into her skin. The feature article and accompanying photographs detail the hyperbolic hotness of the celebrity; Ross McCammon, the article’s author, acknowledges that the pop star’s presence renders him speechless and unable to keep his composure. Interwoven into anecdotes and narrative scenes explicating Rihanna’s desirability as a sexual subject are her statements of her sexual appetite and the pleasure that she finds in particular forms of sexual play that rehearse gendered power inequity and the titillation of pain. That Rihanna’s right arm is carefully positioned both to show the tattoo of the gun aimed at her breast, and that her fingers claw into her flesh, commingle sexual pleasure and pain, erotic desire and violence. Here and elsewhere, Rihanna employs her body as a stage for the exploration of modes of violence structured into hetero- sexual desire and practices. -

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography official website COMMERCIALS (partial list) Verizon, Workday ft. Naomi Osaka, IBM, M&Ms, *Beats by Dre, Absolut, Chase, Kellogg’s, Google, Ellen Beauty, Instagram, AT&T, Apple, Adidas, Gap, Old Navy, Bumble, P&G, eBay, Amazon Prime, **Netflix “A Great Day in Hollywood”, Nivea, Spectrum, YouTube, Checkers, Lexus, Dobel, Comcast XFinity, Captain Morgan, ***Nike, Marriott, Chevrolet, Sky Vodka, Cadillac, UNCF, Union Bank, 02, Juicy Couture, Tacori Jewelry, Samsung, Asahi Beer, Duracell, Weight Watchers, Gillette, Timberland, Uniqlo, Lee Jeans, Abreva, GMC, Grey Goose, EA Sports, Kia, Harley Davidson, Gatorade, Burlington, Sunsilk, Versus, Kose, Escada, Mennen, Dolce & Gabbana, Citizen Watches, Aruba Tourism, Texas Instruments, Sunlight, Cover Girl, Clairol, Coppertone, GMC, Reebok, Dockers, Dasani, Smirnoff Ice, Big Red, Budweiser, Nintendo, Jenny Craig, Wild Turkey, Tommy Hilfiger, Fuji, Almay, Anti-Smoking PSA, Sony, Canon, Levi’s, Jaguar, Pepsi, Sears, Coke, Avon, American Express, Snapple, Polaroid, Oxford Insurance, Liberty Mutual, ESPN, Yamaha, Nissan, Miller Lite, Pantene, LG *2021 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial – Beats by Dre “You Love Me” **2019 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial ***2017 D&AD Professional Awards Winner – Cinematography for Film Advertising – Nike “Equality” MUSIC VIDEOS (partial list) Arianna Grande, Miley Cyrus & Lana Del Rey, Kanye West feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, N.E.R.D. & Rihanna, Jay Z, Charli XCX, Damian Marley, *Beyoncé, Kanye West, Nate Ruess, Kendrick Lamar, Sia, Nicole Scherzinger, Arcade Fire, Bruno Mars, The Weekend, Selena Gomez, **Lana Del Rey, Mariah Carey, Nicki Minaj, Drake, Ciara, Usher, Rihanna, Will I Am, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J, Black Eyed Peas, Pharrell, Robin Thicke, Ricky Martin, Lauryn Hill, Nas, Ziggy Marley, Youssou N’Dour, Jennifer Lopez, Michael Jackson, Mary J. -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

RESUME FINAL 10-7-19.Xlsx

MacGowan Spencer AWARD WINNING MAKEUP + HAIR DESIGNER, GROOMER I MAKEUP DEPT HEAD I SKIN CARE SPECIALIST + BEAUTY EDITOR NATALIE MACGOWAN SPENCER [email protected] www.macgowanspencer.com Member IATSE Local 706 MakeupDepartment Head FEATURE FILMS Director ▪ Hunger Games "Catching Fire" Francis Lawrence Image consultant ▪ “Bad Boys 2” Michael Bay Personal makeup artist to Gabrielle Union ▪ Girl in a Spiders Web Fede Alvarez Makeup character designer for Claire Foy Trilogy leading lady TV SHOWS/ SERIES ▪ HBO Insecure Season 1, 2 + 3 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ NETFLIX Dear White People Season 2 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ FOX Leathal Weapon Season 3 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ ABC Grown-ish Season 3, episode 306, 307, 308, 309 Makeup DEPT HEAD SHORT FILMS Director SHORT FILMS Director ▪ Beastie Boys "Make Some Noise" Adam Yauch ▪ Toshiba DJ Caruso ▪ Snow White Rupert Sanders ▪ "You and Me" Spike Jonze SOCIAL ADVERTISING: FaceBook, Google, Apple COMMERCIALS Director COMMERCIALS Director ▪ Activia Liz Friedlander ▪ Glidden Filip Engstrom ▪ Acura Martin De Thurah ▪ Heineken Rupert Saunders ▪ Acura W M Green ▪ Honda Filip Engstrom ▪ Adobe Rhys Thomas ▪ Hyundai Max Malkin ▪ Allstate Antoine Fuqua ▪ Infinity Carl Eric Rinsch ▪ Apple "Family Ties" Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu ▪ International Delight Renny Maslow ▪ Applebee's Renny Maslow ▪ Pepperidge Renny Maslow ▪ Applebee's Renny Maslow ▪ Hennessey ▪ AT&T Oskar ▪ Jordan Rupert Sanders ▪ AT&T Rupert Saunders ▪ Kia Carl Eric Rinsch ▪ AT&T Filip Engstram ▪ Liberty Mutual Chris Smith ▪ Catching Fire Francis Lawrence ▪ Lincoln Melinda M. ▪ Chevy Filip Engstram ▪ Miller Lite Antoine Fuqua ▪ Cisco Chris Smith ▪ NFL Chris Smith ▪ Comcast Pat Sherman ▪ Nike Rupert Saunders ▪ Cottonelle Renny Maslow ▪ Nissan Dominick Ferro ▪ Crown Royal Frederick Bond ▪ Pistacios Chris smith ▪ Dannon Liz Friedlander ▪ Pistachios Job Chris smith ▪ Disney Renny Maslow Featuring Snoop Dog, Dennis Rodman + Snooki ▪ Dr. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

MTO 23.2: Lafrance, Finding Love in Hopeless Places

Finding Love in Hopeless Places: Complex Relationality and Impossible Heterosexuality in Popular Music Videos by Pink and Rihanna Marc Lafrance and Lori Burns KEYWORDS: Pink, Rihanna, music video, popular music, cross-domain analysis, relationality, heterosexuality, liquid love ABSTRACT: This paper presents an interpretive approach to music video analysis that engages with critical scholarship in the areas of popular music studies, gender studies and cultural studies. Two key examples—Pink’s pop video “Try” and Rihanna’s electropop video “We Found Love”—allow us to examine representations of complex human relationality and the paradoxical challenges of heterosexuality in late modernity. We explore Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of “liquid love” in connection with the selected videos. A model for the analysis of lyrics, music, and images according to cross-domain parameters ( thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, and gestural ) facilitates the interpretation of the expressive content we consider. Our model has the potential to be applied to musical texts from the full range of musical genres and to shed light on a variety of social and cultural contexts at both the micro and macro levels. Received December 2016 Volume 23, Number 2, June 2017 Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory [1.1] This paper presents and applies an analytic model for interpreting representations of gender, sexuality, and relationality in the words, music, and images of popular music videos. To illustrate the relevance of our approach, we have selected two songs by mainstream female artists who offer compelling reflections on the nature of heterosexual love and the challenges it poses for both men and women. -

Voci Di Corridoio

Voci di Corridoio Numero 62—Anno IV settimanale fraccarotto 28 febbraio 2008 ECCEZZZIUNALE VERAMENTE ! La collegialità non si lascia maltrattare da accuse di brigatismo. VdC non fa eccezione e risponde. NESSUNA ECCEZIONE QUELLA TENTAZIONE di Monto CHIAMATA CENSURA di PampaNatale A distanza di alcuni giorni da quel- la riunione generale, che forse sarà Che questo sia un autunno caldo per ricordata per l'inedita iniziativa del il Collegio Fraccaro non c’è dubbio. Se Rettore di ascoltare senza riserve ciò che succede all’ombra delle torri la collegialità, avverto la medesima varca la soglia di piazza Leonardo da sensazione provata al termine del Vinci e corre per chilometri e chilome- suo discorso: che andrebbero af- tri, in lungo e in largo, allora vuol dire frontati troppi argomenti, che insi- che qualcosa è successo. Non so se stono sulla stessa questione, per “il giocattolo si è rotto” ma sicura- fare davvero chiarezza. Ciò non mente qualcosa è scattato. Colpa del- toglie affatto che Panella, con la la matricolatio, colpa dei sardi, colpa lettura degli articoli, la critica dei del Comitato, colpa del Rettore, colpa fatti e le relative incriminazioni, del giornalino: questo non lo so, forse abbia reso un discorso molto ben di tutti e di nessuno. Dall’allagamento strutturato e per giunta coinvol- di alcune camere, per dirla come gli gente; significa bensì che l'impo- estranei (noi quella la si chiama lagu- nente varietà di riferimenti, talora natio), la situazione è precipitata: la fugaci, alla vita del nostro collegio, polizia, Panella, l’adunata generale, alla realtà collegiale pavese, non- chi ha le palle e chi no, le iscrizioni ai ché al concetto stesso di comuni- tornei a rischio. -

Policymaking, Environmental Science, and the Nuclear Complex, 1945-1960

Splitting Atoms, Fracturing Landscapes: Policymaking, Environmental Science, and the Nuclear Complex, 1945-1960 BY ©2013 Neil Shafer Oatsvall Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________ Chairperson Sheyda Jahanbani _________________________ Gregory Cushman _________________________ Johannes Feddema _________________________ Sara Gregg _________________________ Theodore Wilson Date Defended: 7 December 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Neil Shafer Oatsvall certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Splitting Atoms, Fracturing Landscapes: Policymaking, Environmental Science, and the Nuclear Complex, 1945-1960 ________________________________ Chairperson Sheyda Jahanbani Date approved: 2 April 2013 ii ABSTRACT Neil S. Oatsvall, Ph.D. Department of History, May 2013 University of Kansas “Splitting Atoms, Fracturing Landscapes: Policymaking, Environmental Science, and the Nuclear Complex, 1945-1960” examines the implications of an expansive nuclear culture in the postwar United States. This dissertation probes the intersection of Cold War policymaking, environmental science, and the nuclear complex—a shorthand way of discussing the sum set of all nuclear technologies in conjunction with the societal structures and ideologies necessary to implement such technology. Studying a unified nuclear complex corrects for the limitations associated with studying all nuclear technologies as separate entities, something that has created fractured understandings of how splitting the atom affected both natural and human systems. This dissertation shows how U.S. policymakers in the early Cold War interacted with the environment and sought to fulfill their charge to protect the United States and its people while still attempting to ensure future national prosperity. -

Sherrikorhonen-Production Designer

Sherri Korhonen yourdesignteam.tv Production Designer (504) 908-8048 [email protected] Projects *Not a complete list Director Company Job Title 3M Post-It “Fresh Start” and “Go Ahead” Theresa Wingert Fiona Production Designer Alicia Keys ft.Maxwell “Fire We Make” Chris Robinson Robot Films Production Designer Americana Manhasset Catalog Photoshoot Laspata/ DeCaro Laspata/ DeCaro Production Designer Beyonce ft. Jay-Z “Deja Vu” Sophie Muller Oil Factory Prod.Design/Co-Art Direct BP “Tourism Gulf Coast” and “Come Back to Gulf Coast” Mark Traver Cold Harbor Films Production Designer Superbowl XLVII ft. Bud Light Stevie Wonder Samuel Bayer Serial Pictures Art Director “Lucky Chair” and “Journey” ft. “Ultimate Can-Am Spyder Drew Brees Shane Valdes Wondros Production Designer Loophole” Chrysler Superbowl XLVI ft. Clint Eastwood David Gordon Green Chelsea Art Director “Halftime Speech for America” Deborah Cox “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here” Darren Grant Shooting Star Production Designer Depeche Mode “Free Love” John Hillcoat Anonymous Content Production Designer Depeche Mode “Heaven” Timothy Saccenti Radical Media Production Designer Directv “FOYB” ft. Peyton & Eli Manning Bryan Buckley Hungryman Art Director Directv “Voodoo” and “Cop” Harold Einstein Station Film Art Director Entergy “Keep Me Informed” Steve Colby Pogo Pictures Production Designer First Tennessee “Buttons” and “Paintbrush” Iddo Patt Modern Prod Concepts Production Designer “Southern Fried Investigation Discovery Jeanne Kopeck Mrs K. Art Director (Dept Head) Homicide” Jimmmy Buffet “Bama Breeze” Trey Fanjoy Picture Vision Pictures Prod.Design/Co-Art Direct Juvenile “Back That Ass Up” and “U Understand” Dave Meyers FM Rocks Production Designer Lil Wayne “Tha Block is Hot” Dave Meyers FM Rocks Production Designer Maxwell House “Mugs”, “French Press”, and ”Sippy Cup” David Shane O Positive Art Director ft. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H.