Of the Endangered Species Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU Zoo Inquiry Report Findings and Recommendations

1 THE EU ZOO INQUIRY 2011 An evaluation of the implementation and enforcement of EC Directive 1999/22, relating to the keeping of animals in zoos. REPORT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Written for the European coalition ENDCAP by the Born Free Foundation 2 THE EU ZOO INQUIRY 2011 An evaluation of the implementation and enforcement of EC Directive 1999/22, relating to the keeping of animals in zoos. REPORT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 3 CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS USED ............................................ 04 TERMS USED ............................................................... 04 FOREWORD ................................................................. 05 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................ 06 EC ZOOS DIRECTIVE 1999/22, SUCCESS, FAILURE – OR WORK IN PROGRESS? ..... 08 THE EU ZOO INQUIRY 2011 FINDINGS 11 INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 12 METHODOLOGY .......................................................... 14 TRANSPOSITION ........................................................ 17 IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................... 22 ENFORCEMENT ........................................................... 28 COMPLIANCE .............................................................. 30 COUNTRY REPORTS AND UPDATES 41 AUSTRIA............................................................ 42 BELGIUM........................................................... 43 BULGARIA ........................................................ 44 CYPRUS............................................................ -

Toward Successful Reintroductions: the Combined Importance of Species Traits, Site Quality, and Restoration Technique

Kaye: Toward Successful Reintroductions Proceedings of the CNPS Conservation Conference, 17–19 Jan 2009 pp. 99–106 © 2011, California Native Plant Society TOWARD SUCCESSFUL REINTRODUCTIONS: THE COMBINED IMPORTANCE OF SPECIES TRAITS, SITE QUALITY, AND RESTORATION TECHNIQUE THOMAS N. KAYE Institute for Applied Ecology, P.O. Box 2855, Corvallis, Oregon 97339-2855; Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Reintroduction of endangered plant species may be necessary to protect them from extinction, provide connectivity between populations, and reach recovery goals under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. But what factors affect reintroduction success? And which matter more: traits inherent to the species, qualities of the site, or reintroduction technique? Here I propose that all three interact. First, reintroduction success will be highest for endangered species that share traits with non-rare native species, invasive plants, and species that excel in restoration plantings as reviewed from the ecological literature. Ten traits are identified as common to at least two of these groups. Second, reintroductions will do best in habitats ecologically similar to existing wild populations and with few local threats, such as non-native plants and herbivores. And third, the methods used to establish plants, such as planting seeds vs. transplants or selecting appropriate microsites, will influence outcomes. For any reintroduction project, potential pitfalls associated with a particular species, site, or technique may be overcome by integrating information from all three areas. Conducting reintroductions as designed experiments that test clearly stated hypotheses will maximize the amount and quality of information gained from each project and support adaptive management. -

Ecosystem-Level Effects of Keystone Species Reintroduction: a Literature Review Sarah L

REVIEW ARTICLE Ecosystem-level effects of keystone species reintroduction: a literature review Sarah L. Hale1,2 , John L. Koprowski1 The keystone species concept was introduced in 1969 in reference to top-down regulation of communities by predators, but has expanded to include myriad species at different trophic levels. Keystone species play disproportionately large, important roles in their ecosystems, but human-wildlife conflicts often drive population declines. Population declines have resulted in the necessity of keystone species reintroduction; however, studies of such reintroductions are rare. We conducted a literature review and found only 30 peer-reviewed journal articles that assessed reintroduced populations of keystone species, and only 11 of these assessed ecosystem-level effects following reintroduction. Nine of 11 publications assessing ecosystem-level effects found evidence of resumption of keystone roles; however, these publications focus on a narrow range of species. We highlight the deficit of peer-reviewed literature on keystone species reintroductions, and draw attention to the need for assessment of ecosystem-level effects so that the presence, extent, and rate of ecosystem restoration driven by keystone species can be better understood. Key words: ecosystem restoration, ecosystem-level effects, keystone species, population declines, reintroduction species in their ecosystems. Wolves prevent ungulate overpop- Implications for Practice ulation, and in doing so prevent overbrowsing of vegetation • More research into ecosystem-level effects of keystone (McLaren & Peterson 1994), and provide scavengers with car- species reintroduction is required to fully understand if, rion in winters (Wilmers et al. 2003). Sea otters consume sea and to what extent, keystone species act as a restoration urchins (Strongylocentrotus spp.), thereby maintain the integrity tool. -

The Network of Conservatoires Botaniques Nationaux in France Bardin & Moret

The network of Conservatoires Botaniques Nationaux in France Bardin & Moret The network of Conservatoires Botaniques Nationaux in France and the implementation of the GSPC: results of fifteen years of activities Ph. Bardin and J. Moret Conservatoire Botanique National du Bassin parisien, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France Abstract The Conservatoire Botanique National of the Bassin Parisien: a leading role in plant diversity conservation in the French Ministry of Ecology and Sustainable Development (Departement Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversite) In France, the Conservatoires Botaniques Nationaux are responsible for the conservation of plant diversity. The Conservatoire Botanique National of the Bassin Parisien, which comes under the National Museum of Natural History, has five main activities, which are in total accordance with the targets of the GSPC. The communication will present many advancements which have been obtained in these five domains: 1. The ambitious programme of biodiversity inventory: it allows us today to provide a widely accessible list of two thousand known species, with more than three million data items (the seventh GBIF contributor). The database is useful to support public policies for territorial projects including biodiversity 2. The research activity is carried out on very limited size populations and include demographic and genetic studies, the development of protocols and relevant tools for ecological engineering 3. A large programme of ex situ conservation, with a seed bank, an in vitro micropropagation unit and a living collection as a back up for the in situ conservation projects 4. Numerous in situ programmes are carried out: population reinforcement, reintroduction and transplantation. At the same time, an ecological management of habitats is established to protect the ecosystems 5. -

Evaluating the Potential for Species Reintroductions in Canada

Evaluating the Potential for Species Reintroductions in Canada JAY V. GEDIR, TIAN EVEREST, AND AXEL MOEHRENSCHLAGER Centre for Conservation Research, Calgary Zoo, 1300 Zoo Road NE, Calgary, AB, T2E 7V6, Canada, email [email protected] Abstract: Species reintroductions and translocations are increasingly useful conservation tools for restoring endangered populations around the world. We examine ecological and socio- political variables to assess Canada’s potential for future reintroductions. Biologically ideal species would be prolific, terrestrial, herbivorous, behaviorally simple, charismatic, easily tractable, or large enough to carry transmitters for post-release evaluations, and would have small home range requirements. Sociologically, Canada’s large geographic area, low human density, high urban population, widespread protectionist views towards wildlife, and sound economic status should favor reintroduction success. Canada has implemented legislation to safeguard species at risk and, compared to developing countries, possesses substantial funds to support reintroduction efforts. We support the reintroduction guidelines put forth by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) but realize that several challenges regarding these parameters will unfold in Canada’s future. Pressures from the rates of species loss and climate change may precipitate situations where species would need to be reintroduced into areas outside their historic range, subspecific substitutions would be necessary if taxonomically similar individuals are unavailable, -

Conservation Actions

CHAPTER 4 Conservation Actions Table of Contents Take Action! Get Involved! ................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Background and Rationale ................................................................................................................. 9 Conservation Action Classification System .................................................................................... 11 Conservation Action Description ........................................................................................................ 12 Best Practices for Conservation Actions ............................................................................................. 15 International Conservation Actions ................................................................................................ 15 Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 15 Regional Conservation Actions ........................................................................................................ 19 Regional Conservation Needs Program .............................................................................................. 19 Regional Action ............................................................................................................................. -

Finding Correlations Among Successful Reintroduction Programs: an Analysis and Review of Current and Past Mistakes

Finding Correlations among Successful Reintroduction Programs: An Analysis and Review of Current and Past Mistakes by Jillian Estrada A practicum submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Natural Resources and Environment) at the University of Michigan April 2014 Faculty advisor(s): Professor Bobbi Low, Chair Dr. M. Elsbeth McPhee Abstract In the past half century the world has seen a dramatic decline in species. More and more species are being pushed to brink of extinction. In the past, there have been several methods utilized to mitigate these trends, however with the recent surge of local extinctions, reintroductions have become a growing conservation tool. Despite many disadvantages of developing a reintroduction plan, hundreds have been attempted over the past 40 years, with mixed outcomes. Some conservationists have studied the factors associated with success; however the criteria on which their assessments were based were flawed. I attempted to complete my own assessment of successful programs using detailed program information along with life history traits of focal species. My results illustrate the many obstacles faced by reintroduction biologists. Based on the limitations faced throughout this study, I conclude that conservationists must take a step back and address the many issues with current reintroduction protocols prior to attempting any further assessments. My recommended solutions to some of these issues include defining universal criteria for a reintroduction program to be considered successful; monitoring, logging, and disseminating standardized data; and collaborating with captive facilities that have the ability to offer additional support. ii Acknowledgments Advisors Dr. Bobbi S. Low, Co-Chair, Professor of Natural Resources, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan Dr. -

Reintroduction of Captive Animals Into Their Native Habitat: a Bibliography

TITLE: REINTRODUCTION OF CAPTIVE ANIMALS INTO THEIR NATIVE HABITAT: A BIBLIOGRAPHY AUTHOR & INSTITUTION: Kay A. Kenyon, Librarian National Zoological Park Branch Smithsonian Institution Libraries Washington, D.C. DATE: September 1988 LAST UPDATE: August 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS General . 1 Invertebrates . 9 Fish . 11 Reptiles and Amphibians . 13 Birds . 18 Mammals . 35 GENERAL Newsletter: Re-Introduction News. 1990,-- no. 1--. Chairman, RSG: Dr. Mark Stanley Price. Edited by Minoo Rahbar. IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, c/o African Wildlife Foundation, P.O. Box 48177, Nairobi, Kenya. Fax (254)-2-710372; Tel (254)-2-710367. 1968 Petrides, G.A. 1968. Problems in species' introductions. IUCN Bulletin, New Series, 2(7):70-71. 1969 Wayre, P. 1969. The role of zoos in breeding threatened species of mammals and birds in captivity. Biological Conservation, 2(1):47-49. 1977 Brambell, M.R. 1977. Reintroduction. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:112-116. Kear, J. & A.J.Berger. 1977. The problem of breeding endangered species in captivity. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:5-14. Sankhala, K.S. 1977. Captive breeding, reintroduction and nature protection: the Indian experience. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:98-101. 1978 Jungius, H. 1978. Criteria for the reintroduction of threatened species into parts of their former range. In: International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Threatened Deer, pp. 342-352. Morges, Switzerland: IUCN. 1979 Anon. 1979. Reintroduction hazards. Oryx, 15:80. 1980 Campbell, S. 1980. Is reintroduction a realistic goal? In: M.E. Soule and B.A. Wilcox, eds. Conservation Biology: An Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective, pp. 263-269. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinaur. -

Assessing the Potential for the Restoration of Vertebrate Species in the Cairngorms National Park

Assessing the potential for the restoration of vertebrate species in the Cairngorms National Park: a background review © Peter Cairns © David Hetherington © David Hetherington Internal report by Dr David Hetherington Cairngorms National Park Authority Ecology Advisor February 2013 Executive Summary To meet biodiversity objectives from the first National Park Plan, the Cairngorms National Park Authority commissioned this review as a systematic approach to identify vertebrate species that previously inhabited the Cairngorms and which could be subject to conservation action to restore them to the National Park. A review of contemporary and modern literature was carried out to identify which species had occurred in the region in the past, but which are either absent or very localised today because of human activity. The broad scope of the Holocene period – the 10,000 years or so since the end of the Ice Age - when the climate was broadly similar to today, was used to determine nativeness. Experiences from other cultural landscapes in the UK and elsewhere in Europe were called on where relevant to judge the likely potential ecological and socioeconomic impacts of species restoration in the Cairngorms National Park. For each species an account summarises information on their ecological function; national or international conservation and legal status; historical occurrence; potential socio- economic impacts; and experiences of restoration elsewhere. In order to help pinpoint those species which offered the best nature conservation and socio-economic opportunities for the Cairngorms National Park, each was assessed against five key criteria: conservation status; ecological function; potential land management impacts; potential economic contribution; and recolonisation ability. The review identified a long-list of 22 native species whose distribution had been severely impacted on by humans, through activities such as habitat modification, over-exploitation, or persecution. -

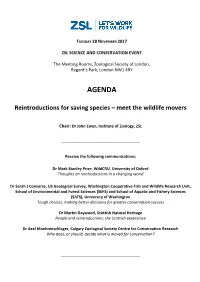

AGENDA Reintroductions for Saving Species

TUESDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2017 ZSL SCIENCE AND CONSERVATION EVENT The Meeting Rooms, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY AGENDA Reintroductions for saving species – meet the wildlife movers Chair: Dr John Ewen, Institute of Zoology, ZSL _______________________________________ Receive the following communications: Dr Mark Stanley Price, WildCRU, University of Oxford Thoughts on reintroductions in a changing world Dr Sarah J Converse, US Geological Survey, Washington Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences (SEFS) and School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences (SAFS), University of Washington Tough choices: making better decisions for greater conservation success Dr Martin Gaywood, Scottish Natural Heritage People and reintroductions: the Scottish experience Dr Axel Moehrenschlager, Calgary Zoological Society Centre for Conservation Research Who does, or should, decide what is moved for conservation? _______________________________________ ZSL SCIENCE AND CONSERVATION EVENTS ABSTRACTS Reintroductions for saving species – meet the wildlife movers Tuesday 28 November 2017 The Meeting Rooms, The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY Thoughts on reintroductions in a changing world Dr Mark Stanley Price, WildCRU, University of Oxford Reintroductions have demonstrably increased over the last 40 years or so, with varying levels of success, usually as assessed by the practitioners. We have seen the development of simple do’s and don’ts about reintroductions evolve -

THE ASIATIC ONE HORNED RHINOCEROS (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in INDIA and NEPAL – ECOLOGY MANAGEMENT and CONSERVATION STRATEGIES

THE ASIATIC ONE HORNED RHINOCEROS (Rhinoceros unicornis) IN INDIA AND NEPAL – ECOLOGY MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION STRATEGIES SATYA PRIYA SINHA BITAPI C.SINHA QAMAR QURESHI 2011 CONTENTS Introduction Morphological Features of Indian Rhinoceros Ecological Aspect Behavioral Aspect Legal Status Conservational Implications Past and Present Distribution Status of Rhino Areas in India and Nepal Rhino Reintroduction Programme in India and Nepal Action Plans for Rhino Conservation in India and Nepal Declaration of IUCN - Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG), Meeting held in Kaziranga NP, Assam, 1999 Declaration of IUCN - Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG), Meeting held in Kaziranga NP, Assam, 2007 Bibliography INTRODUCTION The Asiatic one-horned Rhinoceros/ Greater Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) is perhaps the most endangered species of Indian mega fauna and one of the five remaining species of rhinoceros of an approximately 30 genera that once roamed the world (Nowak and Paradiso, 1883). Rhinoceroses first appeared in the late Eocene period. The oldest Indian rhinoceros like species was Brontops robustus, but the genus Rhinoceros may be traced back to the Pliocene period in northern India, and fossilized remains show that these animals were dwellers of riversides and marshes. In India, the rhinoceros has an old and traditional-linked history. The representation of the rhinoceros ichnographically or its mention in written accounts has been reviewed by a number of authors including Yule and Burnell (1903), Ali(1927), Ettinghausen (1950), Rao (1957) and Rookmaaker (1982). Although most of these quote sixteenth and seventeenth century accounts by medieval authors and other secondhand information’s, the accounts by Al Beruni and Ibn Batuta, two historians and scholars of the same period, are among the more authentic and details one. -

Policies and Issues Surrounding Wildlife Reintroduction Craig R

Hastings Environmental Law Journal Volume 4 Article 8 Number 1 Summer 1997 1-1-1997 Gone Today, Here Tomorrow: Policies and Issues Surrounding Wildlife Reintroduction Craig R. Enochs Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_environmental_law_journal Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Craig R. Enochs, Gone Today, Here Tomorrow: Policies and Issues Surrounding Wildlife Reintroduction, 4 Hastings West Northwest J. of Envtl. L. & Pol'y 91 (1997) Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_environmental_law_journal/vol4/iss1/8 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I. Introduction Ve are a culture of symbols. The wolf and the other predators have become symbols for a slow and difficult process: Man is confronting his ancient world view of dominion. It is a deep struggle, a way of facing the mistakes of our past. For most people, it is occurring at the subcon- scious or subliminal level. But it is occurring."' Wildlife reintroduction has a long tradition in the United States, dating back roughly one hundred years.2 Early experiments with wildlife reintroduction usually involved game species which were desired by hunters and trappers. 3 Gone Today, These programs originated at the state level but were joined by the federal government in the 1930's. 4 Notwithstanding Here Tomorrow these early efforts, federal funding for the restoration of nongame species was not authorized until 1980.