Conservation Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park

A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park David W. Mayhood Part 3 of a Fish Management Plan for Jasper National Park Freshwater Research Limited A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park David W. Mayhood FWR Freshwater Research Limited Calgary, Alberta Prepared for Canadian Parks Service Jasper National Park Jasper, Alberta Part 3 of a Fish Management Plan for Jasper National Park July 1992 Cover & Title Page. Alexander Bajkov’s drawings of bull trout from Jacques Lake, Jasper National Park (Bajkov 1927:334-335). Top: Bajkov’s Figure 2, captioned “Head of specimen of Salvelinus alpinus malma, [female], 500 mm. in length from Jaques [sic] Lake.” Bottom: Bajkov’s Figure 3, captioned “Head of specimen of Salvelinus alpinus malma, [male], 590 mm. in length, from Jaques [sic] Lake.” Although only sketches, Bajkov’s figures well illustrate the most characteristic features of this most characteristic Jasper native fish. These are: the terminal mouth cleft bisecting the anterior profile at its midpoint, the elongated head with tapered snout, flat skull, long lower jaw, and eyes placed high on the head (Cavender 1980:300-302; compare with Cavender’s Figure 3). The head structure of bull trout is well suited to an ambush-type predatory style, in which the charr rests on the bottom and watches for prey to pass over. ABSTRACT I conducted an extensive survey of published and unpublished documents to identify the native fish stocks of Jasper National Park, describe their original condition, determine if there is anything unusual or especially significant about them, assess their present condition, outline what is known of their biology and life history, and outline what measures should be taken to manage and protect them. -

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Classical Biological Control of Arthropods in Australia

Classical Biological Contents Control of Arthropods Arthropod index in Australia General index List of targets D.F. Waterhouse D.P.A. Sands CSIRo Entomology Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 2001 Back Forward Contents Arthropod index General index List of targets The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its primary mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on the Third World. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, GPO Box 1571, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia Waterhouse, D.F. and Sands, D.P.A. 2001. Classical biological control of arthropods in Australia. ACIAR Monograph No. 77, 560 pages. ISBN 0 642 45709 3 (print) ISBN 0 642 45710 7 (electronic) Published in association with CSIRO Entomology (Canberra) and CSIRO Publishing (Melbourne) Scientific editing by Dr Mary Webb, Arawang Editorial, Canberra Design and typesetting by ClarusDesign, Canberra Printed by Brown Prior Anderson, Melbourne Cover: An ichneumonid parasitoid Megarhyssa nortoni ovipositing on a larva of sirex wood wasp, Sirex noctilio. Back Forward Contents Arthropod index General index Foreword List of targets WHEN THE CSIR Division of Economic Entomology, now Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Entomology, was established in 1928, classical biological control was given as one of its core activities. -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

Insect Survey of Four Longleaf Pine Preserves

A SURVEY OF THE MOTHS, BUTTERFLIES, AND GRASSHOPPERS OF FOUR NATURE CONSERVANCY PRESERVES IN SOUTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA Stephen P. Hall and Dale F. Schweitzer November 15, 1993 ABSTRACT Moths, butterflies, and grasshoppers were surveyed within four longleaf pine preserves owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy during the growing season of 1991 and 1992. Over 7,000 specimens (either collected or seen in the field) were identified, representing 512 different species and 28 families. Forty-one of these we consider to be distinctive of the two fire- maintained communities principally under investigation, the longleaf pine savannas and flatwoods. An additional 14 species we consider distinctive of the pocosins that occur in close association with the savannas and flatwoods. Twenty nine species appear to be rare enough to be included on the list of elements monitored by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (eight others in this category have been reported from one of these sites, the Green Swamp, but were not observed in this study). Two of the moths collected, Spartiniphaga carterae and Agrotis buchholzi, are currently candidates for federal listing as Threatened or Endangered species. Another species, Hemipachnobia s. subporphyrea, appears to be endemic to North Carolina and should also be considered for federal candidate status. With few exceptions, even the species that seem to be most closely associated with savannas and flatwoods show few direct defenses against fire, the primary force responsible for maintaining these communities. Instead, the majority of these insects probably survive within this region due to their ability to rapidly re-colonize recently burned areas from small, well-dispersed refugia. -

Saturniidae) of Rio Grande Do Sul State, Brazil

214214 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 63(4), 2009, 214-232 ARSENURINAE AND CERATOCAMPINAE (SATURNIIDAE) OF RIO GRANDE DO SUL STATE, BRAZIL ANDERSONN SILVEIRA PRESTES Laboratório de Entomologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Caixa postal 1429, 90619-900 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; email: [email protected] FABRÍCIO GUERREIRO NUNES Laboratório de Entomologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Caixa postal 1429, 90619-900 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; email: [email protected] ELIO CORSEUIL Laboratório de Entomologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Caixa postal 1429, 90619-900 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; email: [email protected] AND ALFRED MOSER Avenida Rotermund 1045, 93030-000 São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. The present work aims to offer a list of Arsenurinae and Ceratocampinae species known to occur in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. The list is based on bibliographical data, newly collected specimens, and previously existing museum collections. The Arsenurinae are listed in the following genera (followed by number of species): Arsenura Duncan, 1841 (4), Caio Travassos & Noronha, 1968 (1), Dysdaemonia Hübner, [1819] (1), Titaea Hübner, [1823] (1), Paradaemonia Bouvier, 1925 (2), Rhescyntis Hübner, [1819] (1), Copiopteryx Duncan, 1841 (2). Cerato- campinae are listed in Adeloneivaia Travassos, 1940 (3), Adelowalkeria Travassos, 1941 (2), Almeidella Oiticica, 1946 (2), Cicia Oiticica, 1964 (2), Citheronia Hübner, [1819] (4), Citioica Travassos & Noronha, 1965 (1), Eacles Hübner, [1819] (4), Mielkesia Lemaire, 1988 (1), Neocarne- gia Draudt, 1930 (1), Oiticella Travassos & Noronha, 1965 (1), Othorene Boisduval, 1872 (2), Procitheronia Michener, 1949 (1), Psilopygida Michener, 1949 (2), Scolesa Michener, 1949 (3) and Syssphinx Hübner, [1819] (1). -

Dragonflies of Northern Virginia

WILDLIFE OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA Hayhurst’s Scallopwing Southern Broken-Dash Dreamy Duskywing Northern Broken-Dash Sleepy Duskywing Little Glassywing Juvenal’s Duskywing Sachem Horace’s Duskywing Delaware Skipper Wild Indigo Duskywing Hobomok Skipper Common Checkered Skipper Zabulon Skipper Common Sootywing Broad-winged Skipper Swarthy Skipper Dion Skipper Clouded Skipper Dun Skipper Least Skipper Dusted Skipper European Skipper Pepper and Salt Skipper Fiery Skipper Common Roadside Skipper Leonard’s Skipper Ocola Skipper Cobweb Skipper Peck’s Skipper Data Sources: H. Pavulaan, R. Smith, R. Smythe, Tawny-edged Skipper B. Steury (NPS), J. Waggener Crossline Skipper DRAGONFLIES OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA Following is a provisional list of dragonfly species that Other notations: shaded (species you should be able to might be found in appropriate habitats. find in a normal year). PETALTAILS (PETALURIDAE) Midland Clubtail Gray Petaltail Arrow Clubtail Russet-tipped Clubtail DARNERS (AESHNIDAE) Laura’s Clubtail Common Green Darner Elusive Clubtail Comet Darner Black-shouldered Spinyleg Swamp Darner Unicorn Clubtail Cyrano Darner Least Clubtail Harlequin Darner Southern Pygmy Clubtail Taper-tailed Darner Common Sanddragon Occelated Darner Eastern Ringtail Fawn Darner Springtime Darner SPIKETAILS (CORDULEGASTRIDAE) Shadow Darner Tiger Spiketail Twin-spotted Spiketail CLUBTAILS (GOMPHIDAE) Brown Spiketail Dragonhunter Arrowhead Spiketail Ashy Clubtail Lancet Clubtail CRUISERS (MACROMIIDAE) Spine-crowned -

Zoogeography of the Holarctic Species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): Importance of the Bering Ian Refuge

© Entomologica Fennica. 8.XI.l991 Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Bering ian refuge Kauri Mikkola, J, D. Lafontaine & V. S. Kononenko Mikkola, K., Lafontaine, J.D. & Kononenko, V. S. 1991 : Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Beringian refuge. - En to mol. Fennica 2: 157- 173. As a result of published and unpublished revisionary work, literature compi lation and expeditions to the Beringian area, 98 species of the Noctuidae are listed as Holarctic and grouped according to their taxonomic and distributional history. Of the 44 species considered to be "naturall y" Holarctic before this study, 27 (61 %) are confirmed as Holarctic; 16 species are added on account of range extensions and 29 because of changes in their taxonomic status; 17 taxa are deleted from the Holarctic list. This brings the total of the group to 72 species. Thirteen species are considered to be introduced by man from Europe, a further eight to have been transported by man in the subtropical areas, and five migrant species, three of them of Neotropical origin, may have been assisted by man. The m~jority of the "naturally" Holarctic species are associated with tundra habitats. The species of dry tundra are frequently endemic to Beringia. In the taiga zone, most Holarctic connections consist of Palaearctic/ Nearctic species pairs. The proportion ofHolarctic species decreases from 100 % in the High Arctic to between 40 and 75 % in Beringia and the northern taiga zone, and from between 10 and 20 % in Newfoundland and Finland to between 2 and 4 % in southern Ontario, Central Europe, Spain and Primorye. -

Lepidoptera of a Raised Bog and Adjacent Forest in Lithuania

Eur. J. Entomol. 101: 63–67, 2004 ISSN 1210-5759 Lepidoptera of a raised bog and adjacent forest in Lithuania DALIUS DAPKUS Department of Zoology, Vilnius Pedagogical University, Studentų 39, LT–2004 Vilnius, Lithuania; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Lepidoptera, tyrphobiontic and tyrphophilous species, communities, raised bog, wet forest, Lithuania Abstract. Studies on nocturnal Lepidoptera were carried out on the Laukėnai raised bog and the adjacent wet forest in 2001. Species composition and abundance were evaluated and compared. The species richness was much higher in the forest than at the bog. The core of each lepidopteran community was composed of 22 species with an abundance of higher than 1.0% of the total catch. Tyrpho- philous Hypenodes humidalis (22.0% of all individuals) and Nola aerugula (13.0%) were the dominant species in the raised bog community, while tyrphoneutral Pelosia muscerda (13.6%) and Eilema griseola (8.3%) were the most abundant species at the forest site. Five tyrphobiotic and nine tyrphophilous species made up 43.4% of the total catch on the bog, and three and seven species, respectively, at the forest site, where they made up 9.2% of all individuals. 59% of lepidopteran species recorded on the bog and 36% at the forest site were represented by less than five individuals. The species compositions of these communities showed a weak similarity. Habitat preferences of the tyrphobiontic and tyrphophilous species and dispersal of some of the species between the habi- tats are discussed. INTRODUCTION (1996). Ecological terminology is that of Mikkola & Spitzer (1983), Spitzer & Jaroš (1993), Spitzer (1994): tyrphobiontic The insect fauna of isolated raised bogs in Europe is species are species that are strongly associated with peat bogs, unique in having a considerable portion of relict boreal while tyrphophilous taxa are more abundant on bogs than in and subarctic species (Mikkola & Spitzer, 1983; Spitzer adjacent habitats. -

First Record of Citheronia Regalis (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) Feeding on Cotinus Obovatus (Anacardiaceae) Author(S): Gary R

First Record of Citheronia regalis (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) Feeding on Cotinus obovatus (Anacardiaceae) Author(s): Gary R. Graves Source: Florida Entomologist, 100(2):474-475. Published By: Florida Entomological Society https://doi.org/10.1653/024.100.0210 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1653/024.100.0210 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Scientific Notes First record of Citheronia regalis (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) feeding on Cotinus obovatus (Anacardiaceae) Gary R. Graves1,2,* The regal moth (Citheronia regalis F.; Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) 2016) shows historic and recent records of C. regalis for only 11 of was historically distributed in eastern North America from southern the 34 counties in which natural populations of smoketree have been New England and southern Michigan, south to southern Florida, and documented (Davis & Graves 2016). west to eastern Nebraska and eastern Texas (Tuskes et al. -

Contributions Toward a Lepidoptera (Psychidae, Yponomeutidae, Sesiidae, Cossidae, Zygaenoidea, Thyrididae, Drepanoidea, Geometro

Contributions Toward a Lepidoptera (Psychidae, Yponomeutidae, Sesiidae, Cossidae, Zygaenoidea, Thyrididae, Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Mimalonoidea, Bombycoidea, Sphingoidea, & Noctuoidea) Biodiversity Inventory of the University of Florida Natural Area Teaching Lab Hugo L. Kons Jr. Last Update: June 2001 Abstract A systematic check list of 489 species of Lepidoptera collected in the University of Florida Natural Area Teaching Lab is presented, including 464 species in the superfamilies Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Mimalonoidea, Bombycoidea, Sphingoidea, and Noctuoidea. Taxa recorded in Psychidae, Yponomeutidae, Sesiidae, Cossidae, Zygaenoidea, and Thyrididae are also included. Moth taxa were collected at ultraviolet lights, bait, introduced Bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum), and by netting specimens. A list of taxa recorded feeding on P. notatum is presented. Introduction The University of Florida Natural Area Teaching Laboratory (NATL) contains 40 acres of natural habitats maintained for scientific research, conservation, and teaching purposes. Habitat types present include hammock, upland pine, disturbed open field, cat tail marsh, and shallow pond. An active management plan has been developed for this area, including prescribed burning to restore the upland pine community and establishment of plots to study succession (http://csssrvr.entnem.ufl.edu/~walker/natl.htm). The site is a popular collecting locality for student and scientific collections. The author has done extensive collecting and field work at NATL, and two previous reports have resulted from this work, including: a biodiversity inventory of the butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea & Papilionoidea) of NATL (Kons 1999), and an ecological study of Hermeuptychia hermes (F.) and Megisto cymela (Cram.) in NATL habitats (Kons 1998). Other workers have posted NATL check lists for Ichneumonidae, Sphecidae, Tettigoniidae, and Gryllidae (http://csssrvr.entnem.ufl.edu/~walker/insect.htm). -

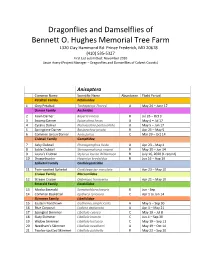

Bennett O. Huhges Ode List

Dragonflies and Damselflies of Bennett O. Hughes Memorial Tree Farm 1320 Clay Hammond Rd. Prince Frederick, MD 20678 (410) 535-5327 First List submitted: November 2020 Jason Avery (Project Manager – Dragonflies and Damselflies of Calvert County) Anisoptera Common Name Scientific Name Abundance Flight Period Petaltail Family Petaluridae 1 Grey Petaltail Tachopteryx Thoreyi U May 24 – June 17 Darner Family Aeshnidae 2 Fawn Darner Boyeria vinosa R Jul 26 – Oct 3 3 Swamp Darner Epiaeschna heros U May 4 – Jul 17 4 Cyrano Darner Nasiaeschna pentacantha U May 5 – Jun 17 5 Springtime Darner Basiaeschna janata R Apr 21 – May 5 6 Common Green Darner Anax junius C Mar 29 – Oct 14 Clubtail Family Gomphidae 7 Ashy Clubtail Phanogomphus lividu U Apr 23 – May 4 8 Sable Clubtail Stenogomphurus rogersi R May 10 – Jun 14 9 Laura’s Clubtail Stylurus laurae Williamson R July 16, 2020 (1 record) 10 Dragonhunter Hagenius brevistylus R Jun 16 – Aug 19 Spiketail Family Cordulegastridae 11 Twin-spotted Spiketail Cordulegaster maculata R Apr 23 – May 10 Cruiser Family Macromiidae 12 Stream Cruiser Didymops transversa U Apr 21 – May 10 Emerald Family Corduliidae 13 Mocha Emerald Somatochlora linearis R Jun - Sep 14 Common Baskettail Epitheca cynosura C Apr 1 to Jun 14 Skimmer Family Libellulidae 15 Eastern Pondhawk Erythemis simplicicollis A May 5 – Sep 30 16 Blue Corporal Ladona deplanata A Apr 1 – May 21 17 Spangled Skimmer Libellula cyanea C May 19 – Jul 8 18 Slaty Skimmer Libellula incesta C Jun 4 – Sep 30 19 Widow Skimmer Libellula luctuosa C May 19 – Sep