'Live' and 'Dead' in Popular Electronic Music Performances in Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magenta281440

Y50 M Key 23 C K GRAY 50 Y M Key 22 C K GRAY 50 Y M Key 21 C K GRAY 50 Y M C Key 20 K GRAY 75 Y M Key 19 C K GRAY 75 Y M Key 18 C K GRAY 75 Y M Key 17 C K GRAY 75 Y M Key 16 C K GRAY STAR Y M Key 15 C K GRAY STAR Y M Key 14 C K GRAY STAR Y M Key 13 C K GRAY STAR Y Part No. K-28-4(D) M C Key 12 K Komori/GATF GRAY The Bridge of Central Mass achusetts P 4 Mann Street, Worcester MA 01602 Y M Key 11 C K Fall 2018 GRAY 1/2/3/4 Y 12 34 Y M Key 10 Exciting News from Alternatives Unlimited and The Bridge of Central Mass. C K We are now “Open Sky Community Services!” GRAY 1/2/3/4 M 12 34 Y We are very pleased to announce that following the affiliation of our two M organizations last summer, we have now come together under one name – Key 9 C Open Sky Community Services. The new name is a dba (doing business as) K of Alternatives and The Bridge. Both organizations have retained their GRAY 501(c)3 status, and donations can be made to either Alternatives, The Bridge 1/2/3/4 C 12 34 or the dba of Open Sky Community Services. Y Last year, the two agencies decided to explore what it might be like if they M Key 8 came together as one. -

Live Performance Where Congruent Musical, Visual, and Proprioceptive Stimuli Fuse to Form a Combined Aesthetic Narrative

Soma: live performance where congruent musical, visual, and proprioceptive stimuli fuse to form a combined aesthetic narrative Ilias Bergstrom UCL A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 1 I, Ilias Bergstrom, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract Artists and scientists have long had an interest in the relationship between music and visual art. Today, many occupy themselves with correlated animation and music, called ‗visual music‘. Established tools and paradigms for performing live visual music however, have several limitations: Virtually no user interface exists, with an expressivity comparable to live musical performance. Mappings between music and visuals are typically reduced to the music‘s beat and amplitude being statically associated to the visuals, disallowing close audiovisual congruence, tension and release, and suspended expectation in narratives. Collaborative performance, common in other live art, is mostly absent due to technical limitations. Preparing or improvising performances is complicated, often requiring software development. This thesis addresses these, through a transdisciplinary integration of findings from several research areas, detailing the resulting ideas, and their implementation in a novel system: Musical instruments are used as the primary control data source, accurately encoding all musical gestures of each performer. The advanced embodied knowledge musicians have of their instruments, allows increased expressivity, the full control data bandwidth allows high mapping complexity, while musicians‘ collaborative performance familiarity may translate to visual music performance. The conduct of Mutable Mapping, gradually creating, destroying and altering mappings, may allow for a narrative in mapping during performance. -

Beyond Live Digital Innovation in the Performing Arts Executive Summary

Research briefing: February 2010 Beyond live Digital innovation in the performing arts Executive summary The UK has in recent years undergone a digital revolution. New technologies such as digital TV, music downloads and online games are ripping up established business models. Last year, the UK became the first major economy where advertisers spent more on internet advertising than on TV advertising. This digital revolution has caused upheaval in the creative industries – in some sectors, it has enabled creative businesses to reach audiences in new ways that were unimaginable in the 1. The NT Live research forms analogue age; but in others it has ‘cannibalised’ their established revenue streams. In all cases, part of NESTA’s wider study, led by Hasan Bakhshi and digital technologies have produced seismic changes in consumer expectations and behaviour, Professor David Throsby, and social media platforms are becoming more important as venues for the discovery and on innovation in cultural organisations. A full research discussion of creative content. report will be published in Spring 2010. Unlike film and recorded music, live performance organisations produce ‘experiential goods’ whose features are less easy to translate digitally. Yet, digital technologies are impacting on live performance bodies such as theatres, live music, opera and dance companies too. The National Theatre’s NT Live broadcasts of live productions to digital cinemas may contain broader lessons for innovating organisations in the performing arts sector. With this in mind, NESTA has been conducting an in-depth research study on the two NT Live pilots that were broadcast last year – Phèdre on 25th June and All’s Well That Ends Well on 1st October.1 The research shows how this innovation has allowed the National to reach new audiences for theatre, not least by drawing on established relationships between cinemas and their patrons all over the country. -

Media & Entertainment

Media & Entertainment: Observations of the Effect of Covid-19 & Economic Uncertainty Mike Lorenc: Head of Industry - Ticketing & Live Events, Google @mlorenc Some new interesting stats Screengrab chart example Screengrab chart example Screengrab chart example We are more “online” than ever before MINUTES SPENT ONLINE | MARCH DAILY TIME SPENT WITH MEDIA | 2020 PREDICTED 2T 13.6 More than hours per day any other month in history An increase of more than an hour since last year -- +19% +15% significantly more than increases in the past several years YOY February Levels are expected to stay permanently elevated compared to 2019, though some attrition is likely Source: Comscore April 2020; eMarketer April 2020 Screengrab chart example Consumer Thoughts Globally, ~40% are in the acclimation phase and say they have adapted to the restrictions and settled into new routines. Source: Ipsos COVID-19 tracker, CA, US, AU, BR, FR, CH, IT, ES, IN, JP, MX, RU, ZA, SK, n=16,000 18+, May 21- 24. Consumer Thoughts There are mixed feelings on when to open back up. People in BR (71%), IN (69%), MX and KR (65%), JP and the UK (62%) and the US (60%) say we need to wait before opening businesses. Those in hard hit countries like CN (65%) and IT (64%) say the risk is minimal if people follow new rules as the economy needs to get moving again. Source: Ipsos weekly C-19 tracker, 16 markets, n=16,000+, conducted from May 21 to 24. Link Recovery will play out locally Market-by-market policies and consumer mindset will help frame recovery strategies. -

Where to Beyond Live-Streaming? Keeping Parish Communities Dynamic During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Where to beyond live-streaming? Keeping parish communities dynamic during the COVID-19 outbreak 2. AIM FOR ENGAGEMENT You’ve probably heard talk of ‘views’ of videos and An online presence is only ministry if it live-stream Masses. Many parishes are seeing digital leads to encounter, conversion, sacrament attendance numbers far higher than their usual reception and transformed lives in the physical attendance numbers. That’s amazing and very real world. encouraging. o all of a sudden you’re online like you’ve never However, views are far less valuable than engagement. been before. You are live-streaming or recording Viewers will eventually click away unless they begin SMasses, and/or you are providing links to other to participate and become engagers. We need to Masses and prayer resources for your parishioners. But intentionally move our online congregations from there’s a long road ahead, and no one knows exactly viewers to engagers, who are more likely to return and where all of this might land when the pandemic is to dig deeper. over. How can you optimise your digital engagement Here are some ideas to engage: now and sow the seeds of a more intentional digital • Share your vision for your parish during this time. presence in the future? What are you doing? Who are you reaching? How Like a tin of paint, online presence is all about the can people connect? application. Paint is not much use in the tin. Similarly, • Communicate frequently, over a number of online initiatives are not much use if they stay there. -

Economic Reflections of the Transformation of Social

ECONOMIC REFLECTIONS OF THE TRANSFORMATION OF SOCIAL DISTANCE CONCEPT IN EVERYDAY LIFE AFTER COVID-19 TO VIRTUAL 1 CONTACT Kafkas University Economics and Administrative Sciences Faculty KAUJEASF Article Submission Date: 07.06.2021 Accepted Date: 22.06.2021 Vol. 12, Issue 23, 2021 ISSN: 1309 – 4289 E – ISSN: 2149-9136 Seray BİLİCİ ABSTRACT Being aware of Master Graduate Student its own self through social interaction with other Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University people, humanity is discovering new ways to School of Graduate Studies, M.A. meet the need for socialization and to interact Program in Media and Cultural with other people based on communication in Studies the 21st century. The social isolation that Çanakkale, Turkey, emerged with the Covid-19 pandemic is an [email protected] important obstacle to the social life of modern ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4938-5939 people and the sustainability of the entertainment industry. However, in line with the need for socialization, people create their Arif YILDIRIM own online social activities by overcoming these Asst. Prof.Dr. obstacles with the communication technologies Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University of the age. This new sector, which emerged at a Faculty of Communication, time of global crisis, allows the formation of new Journalism, economic capital of digitalization. Within the Çanakkale, Turkey, scope of the study, the adaptation of the [email protected] entertainment sector, which experienced a ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4446-4865 shrinkage in its economic volume during the pandemic, to the digital world as a way of salvation is examined. Various online activities carried out in line with this review have been examined in detail, and the future of the sector is discussed with the findings obtained. -

Pm Maghrib: 6:27 Pm HIGH : 42°C LOW : 31°C Isha: 7:57 Pm

QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune FRIDAY JULY 17, 2020 DHU AL-QA’DA 26, 1441 VOL.13 NO. 5001 QR 2 Fajr: 3:26 am Dhuhr: 11:40 am FINE Asr: 3:05 pm Maghrib: 6:27 pm HIGH : 42°C LOW : 31°C Isha: 7:57 pm World 6 Business 7 Sports 9 UK accuses Russia of Qatar has advantage Starting at Al Bayt Stadium vaccine research hacking, over other LNG is a great motivation for us: vote meddling producers: GECF Qatar coach Sanchez AMIR MEETS US CENTCOM COMMANDER PM HONOURS DISTINGUISHED TRAINEES OF FIFTH MANDATORY QUALIFYING COURSE OF CIVIL UNIVERSITY GRADUATES Qualifying course grads a qualitative addition to homeland security: PM 103 trainees from MoI, Lekhwiya His Highness The Amir of State of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani met Commander of the and Amiri Guard complete United States Central Command in the Middle East General Kenneth McKenzie and his accompanying mandatory qualifying course delegation at Al Bahr Palace on Thursday. During the meeting, they reviewed the strategic cooperation relations between the two friendly countries and the ways of enhancing them, especially in the military and defence elds. They also discussed joint efforts to enhance the security and stability of the region. In this regard, the general expressed his thanks to HH The Amir for hosting the American forces at Al Udeid e graduates receive military, Air Base and for the pivotal role of Qatar as a major partner in combating terrorism. (QNA) athletic, police and academic training over six months A new uniform for the police Amir condoles with Somali president force was adopted QNA DOHA TNN & QNA DOHA HIS Highness The Amir of State of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin PRIME Minister and Minister of Inte- Prime Minister and Minister of Interior HE Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa bin Abdulaziz Al Thani Hamad Al Thani on Thursday rior HE Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa bin attends the graduation ceremony of the fth mandatory qualifying course for civil sent a cable of condolences to Abdulaziz Al Thani has affirmed that university graduates at the Police Training Institute on Thursday. -

Productvoorraad

Productvoorraad Hieronder vind je een moment opname van de voorraad op 07-10-2021. Titel Artiest Voorraad Mo'Complete - Vol.2 AB6IX 678 Standard Soft Sleeve 10stk Ultra Pro 173 No Easy [Limited Edition] Stray Kids 157 STICKER Rood (Poster) NCT127 75 Zero Fever Part. 3 Groen (Poster) Ateez 60 Zero Fever Part. 3 Blauw (Poster) Ateez 60 Zero Fever Part. 3 Oranje (Poster) Ateez 60 Skool Luv Affair 2nd Mini Album : Special BTS 59 Addition (Poster) Stray Kids - No Easy (Poster SET) --- 40 Titel Artiest Voorraad ATEEZ - Fever pt2 - Blauw (Poster) --- 39 BTS - Skool Luv Affair (Poster) --- 38 Ateez - Fever pt 2 - Rood (Poster) --- 37 No Easy (Poster B Type) Stray Kids 31 No Easy (Poster C Type) Stray Kids 30 No Easy (Poster D Type) Stray Kids 30 Twice - Taste Of Love - Wit (Poster) --- 24 STICKER Seoul City (Poster) NCT127 24 Eternal Groen (Poster) Young K 24 No Easy (Poster A Type) Stray Kids 22 Treasure - Effect (Poster) --- 21 EXO - Don't Fight The Feeling - Groep --- 21 (Photobook Ver.) Poster BTS - Butter - Strand (Poster) --- 19 Day6 - Gluon (Poster) --- 17 True Beauty - Original Sound Track (Poster) --- 17 Titel Artiest Voorraad Vol.3 [STICKER] (Sticker ver) (Photobook NCT 127 17 ver) Got7 - Last piece roze liggend (Poster) --- 16 Twice - Taste Of Love - Donker Blauw --- 16 (poster) BTS - Butter - Dieven (Poster) --- 16 BTS - Official Lightstick Map Of the Soul --- 15 Twice - Taste Of Love - Pink (poster) --- 14 LOONA - & - Deur (Poster) --- 14 Dreamcather - Road to Utopia (Poster) --- 13 DAY6 - Negentropy - Wonpil (Poster) --- 13 Treasure - [THE FIRST STEP : CHAPTER --- 12 TWO] (Poster) DAY6 - Negentropy - YoungK (Poster) --- 12 Mixtape Stray Kids 11 Shinee - z-w staand (Poster) --- 11 DAY6 - Negentropy - Sungjin (Poster) --- 11 Dystopia : Road To Utopia (D ver) DreamCatcher 10 Titel Artiest Voorraad Seventeen - Your Choice - IJs (poster) --- 10 A.C.E - Siren: Dawn - Blauw (Poster) --- 10 Memories of 2020 BLU-RAY BTS 10 Oneus - Binary Code - Blauw (Poster) --- 9 Twice - More & More - C Ver. -

Embargoed Until 8:30 Am KST on October 28

ㅇ Embargoed until 8:30 am KST on October 28 Hyundai and SM Entertainment Present ‘The All-New Tucson, Beyond DRIVE’ Innovative Virtual Showcase for Hot New SUV The livestreamed event will use SM Entertainment’s online concert platform ‘Beyond LIVE’ with augmented reality technology and feature a performance by a globally beloved K-Pop artist Hyundai continues to leverage the latest digital presentation technologies to roll out its all-new Tucson SUV The event will be livestreamed at 10 p.m. (KST) on November 1, viewable at the HyundaiWorldwide YouTube channel SEOUL, Oct. 28, 2020 — Hyundai Motor Company announced today it will host an innovative virtual event ‘The All-New Tucson, Beyond DRIVE’, showcasing the recently launched Tucson SUV, one of Hyundai’s best-selling vehicles around the world. Working with SM Entertainment, Korea’s leading entertainment company, the online event will use augmented reality (AR) / extended reality (XR) technology and feature a performance by a globally beloved K-Pop artist using the AR concert platform Beyond LIVE. The event is designed to tell a compelling musical story about the all-new Tucson SUV while providing an immersive, engaging experience for the audience. Through the virtual showcase, Hyundai will highlight the SUV lifestyle and its vision for the new Tucson in a format that reaches highly coveted Millennial and Gen Z consumers who rely on online platforms for news, information, shopping and entertainment. The event will be livestreamed at 10 p.m. (KST) on November 1, viewable at the HyundaiWorldwide YouTube channel. Hyundai continues to leverage the latest digital presentation technologies to roll-out its all-new Hyundai Motor Company 12, Heolleung-ro, Seochogu, T +82 2 3464 2128 www.hyundai.com Seoul, 137-938, Korea Tucson, which launched via global livestream in September. -

Music Industry in Crisis: the Impact of a Novel Coronavirus on Touring Metal Bands, Promoters, and Venues Kyle J

1 Music industry in crisis: The impact of a novel coronavirus on touring metal bands, promoters, and venues Kyle J. Messick https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0452-0922 Abstract In March of 2020 the world began to take widespread preventative measures against the spread of a novel coronavirus through travel restrictions, quarantines, and limitations on social gatherings. These restrictions resulted in the immediate closing of many businesses, including concerts venues, and also put an abrupt end to live music performances across Europe and the United States. This had immediate implications for touring bands, as bands earn most of their income touring, and many found themselves in a situation where they experienced substantial financial losses alongside negative affective ramifications. This article utilized evidence from qualitative interviews and public statements to draw inferences about the impact of COVID-19 on the music industry, with a particular focus on touring musicians and their respective managers, promoters, booking agencies, and record labels. Musicians reported negative affective and financial ramifications as a result of COVID-19, but they also reported overwhelming support from metal music fans that made the fallout from the pandemic less severe. Further inferences were drawn about how the closures of concert venues adversely impacted the communities dependent on them, as concerts serve a stimulating role for surrounding businesses. Keywords: coronavirus, pandemic, music industry, COVID-19, musicians, coronavirus, affect, financial loss The 2020 outbreak of a novel coronavirus The year 2020 had an immense and likely lasting negative impact on many industries, including the music industry, due to a contagious outbreak of a novel coronavirus known as COVID-19. -

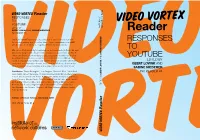

Reader Reader

Reader RESPONSES TO YOUTUBE EDITED BY GEERT LOVINK AND SABINE NIEDERER INC READER #4 R E The Video Vortex Reader is the first collection of critical texts to deal with R the rapidly emerging world of online video – from its explosive rise in 2005 with YouTube, to its future as a significant form of personal media. After years of talk about digital convergence and crossmedia platforms we now witness the merger of the Internet and television at a pace no-one predicted. These contributions from scholars, artists and curators evolved from the first SABINE NIEDE two Video Vortex conferences in Brussels and Amsterdam in 2007 which fo- AND cused on responses to YouTube, and address key issues around independent production and distribution of online video content. What does this new dis- tribution platform mean for artists and activists? What are the alternatives? T LOVINK Contributors: Tilman Baumgärtel, Jean Burgess, Dominick Chen, Sarah Cook, R Sean Cubitt, Stefaan Decostere, Thomas Elsaesser, David Garcia, Alexandra GEE Juhasz, Nelli Kambouri and Pavlos Hatzopoulos, Minke Kampman, Seth Keen, Sarah Késenne, Marsha Kinder, Patricia Lange, Elizabeth Losh, Geert Lovink, Andrew Lowenthal, Lev Manovich, Adrian Miles, Matthew Mitchem, Sabine DITED BY Niederer, Ana Peraica, Birgit Richard, Keith Sanborn, Florian Schneider, E Tom Sherman, Jan Simons, Thomas Thiel, Vera Tollmann, Andreas Treske, Peter Westenberg. Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2008 ISBN 978-90-78146-05-6 Reader 2 Reader RESPONSES TO YOUTUBE 3 Video Vortex Reader: Responses to YouTube Editors: Geert Lovink and Sabine Niederer Editorial Assistance: Marije van Eck and Margreet Riphagen Copy Editing: Darshana Jayemanne Design: Katja van Stiphout Cover image: Orpheu de Jong and Marco Sterk, Newsgroup Printer: Veenman Drukkers, Rotterdam Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2008 Supported by: XS4ALL Nederland and the University of Applied Sciences, School of Design and Communication. -

Stream Media Corporation / 4772

Stream Media Corporation / 4772 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2021.07.20 LAST UPDATE: 2021.08.11 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. Stream Media Corporation/ 4772 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.08.11 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------